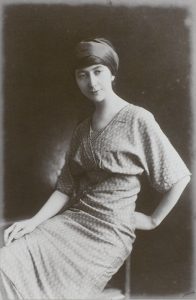

Juliette Roche

Juliette Roche, Demi-cercle, Paris, La Cible, 1920

→Juliette Roche, exh. cat., galerie Miroir, Montpellier, (15–28 December 1962), Montpellier, galerie Miroir, 1962

→Burke Carolyn, “Recollecting Dada: Juliette Roche”, in Sawelson-Gorse Naomi (ed.), Women in Dada: Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2001

Juliette Roche, l’insolite, Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie, Besançon [May 19–September 19, 2021], Musée d’art Moderne et Contemporain, Les Sables-d’Olonne [February 6–May 22, 2022], Musée Estrine, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence [July 17–December 23, 2022]

→Juliette Roche, galerie Miroir, Montpellier, 15–28 December 1962

→Œuvres de Janine Aghion, Madeleine Bunoust, Juliette Roche, Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, Paris, 2–7 March 1914

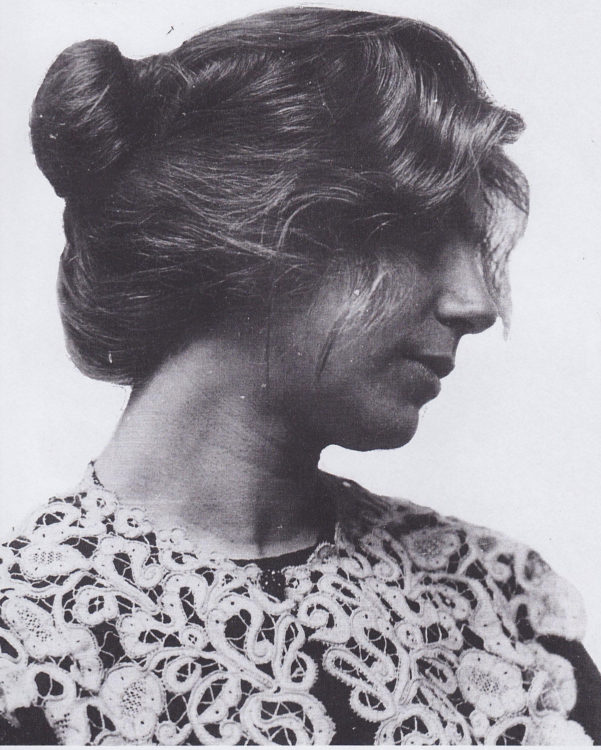

French Painter and Writer.

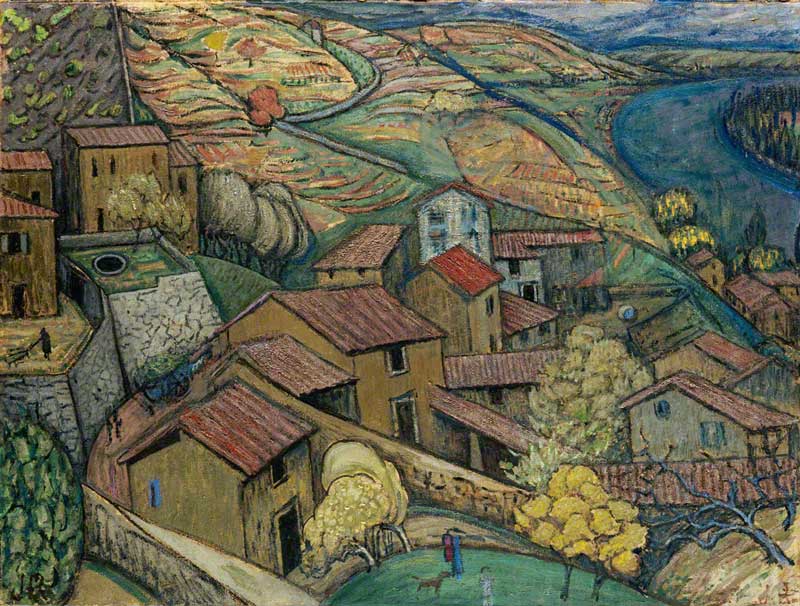

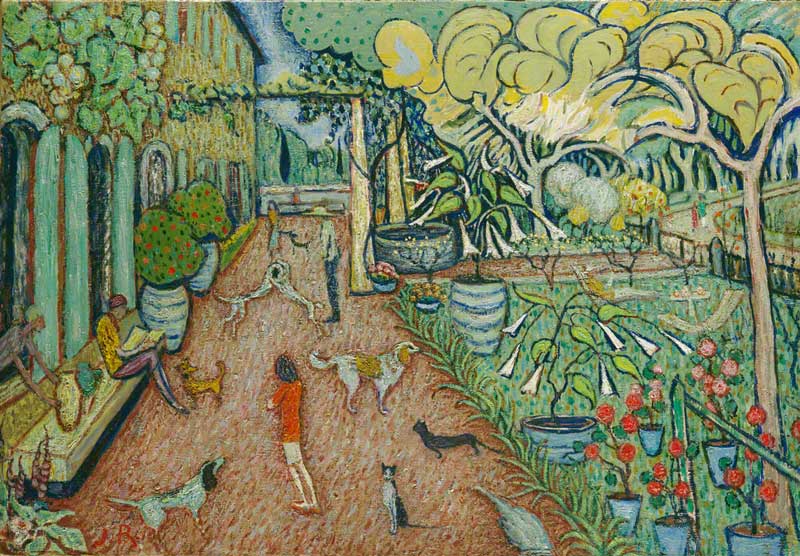

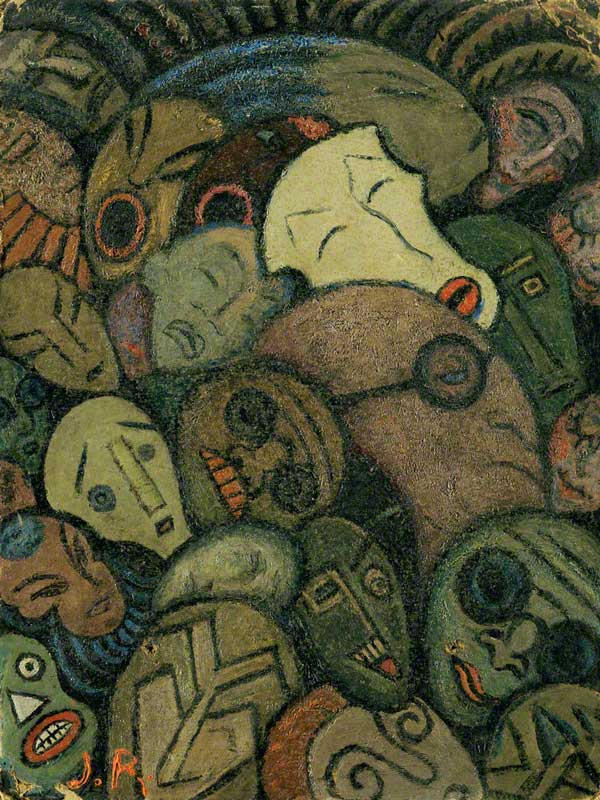

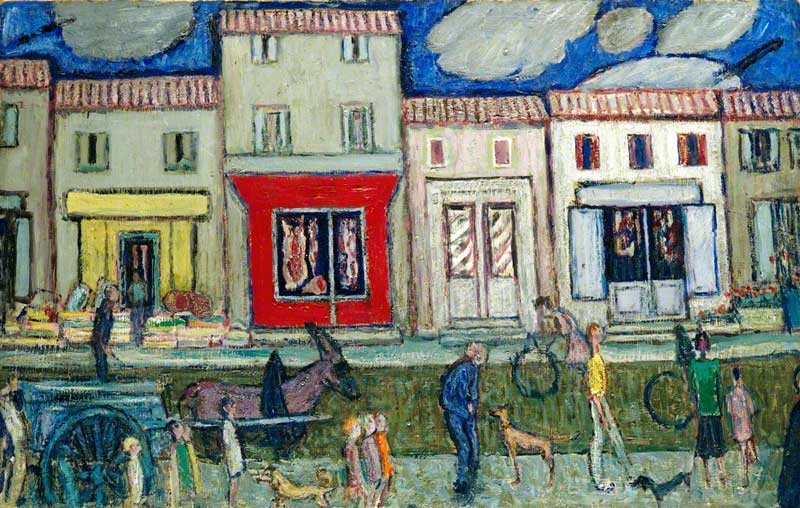

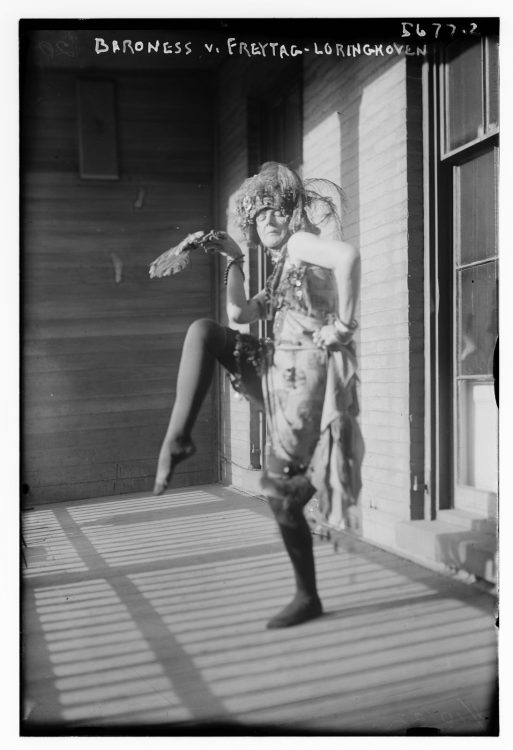

Juliette Roche frequented the Parisian art scene from a young age, thanks to her godmother, the countess Greffulhe, and her father’s godson, Jean Cocteau. Supported by her father, Jules Roche, an important political figure, she studied painting at the Ranson Academy. Adopted early on by the nabis, she discovered Cubism in 1912, and split away from Félix Ballotton and Maurice Denis. In 1913, a groundbreaking year, she showed her work at the Salon des indépendants, and began writing poetry, inserting clichéd phrases, such as advertising slogans, into the poetic fabric. She also began experimenting with innovative typography, which would become even more iconoclastic in 1917, with her pieces Brevoort and Pôle tempéré. Her first solo show took place at the galerie Bernheim-Jeune in 1914. When war was declared, Roche and her future husband, the cubist Albert Gleizes, confirmed pacifists, traveled to New York, where Duchamp introduced them into the circle of collectors that included Louis and Walter Arensberg. Starting in 1915, she took part in Dada activities, along with Duchamp and Picabia.

After a long trip to Barcelona she and her husband, who were showing at the galerie Dalmau, returned to New York. There, Roche collaborated with Duchamp on the preparation of the first exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists (1917), where she showed some Dada-inspired works. Experimenting with the figurative, she created her piece Nature morte au hachoir [Still life with cleaver], in which the blade reflects a disjointed image of war. In 1919, newly returned to Paris, she began writing her story, La Minéralisation de Dudley Craving Mac Adam. Published in 1924, the story evoked the adventures of Arther Cravan and other artists in exile in New York. In 1921 her poetry État… colloïdal [Coloidal state], appeared in Vincente Huidrobro’s periodical, Creación. In 1927, she and her husband founded, the Moly-Sabata artists’ residence in Sablons, which offered studios and workshops, and brought together Anne Dangar (1885–1951) and Jacques Plasse Le Caisne, among others. Thus Roches became a fervent supporter of arts education for the working class. Throughout the rest of her life she occasionally participated in collective exhibitions. In 1962 a major retrospective at the galerie Miroir in Montpellier was devoted to her, but it is since the 1990s especially her role in the Dada movement has been reconsidered.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Juliette Roche : le mouvement cubiste (INA)

Juliette Roche : le mouvement cubiste (INA)