June Beer

Morris, Courtney Desiree, ‘To Defend This Sunrise: Race, Place, and Creole Women’s Political Subjectivity on the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua’, PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2012, p.115-210

→LaDuke, Betty, ‘June Beer: An Artist of New Nicaragua’, in Africa Through the Eyes of Women Artists, Trenton, Africa World Press, 1991, p.141-148

→LaDuke, Betty, ‘June Beer: Nicaraguan Artist’, Sage 3, no. 2, 1986, p.35-39

→LaDuke, Betty, ‘June Beer’s Story’, Heresies 20, 1986, p.54-57

Homenaje a June Beer, curated by Oliver Martínez-Kandt. X Bienal de Nicaragua, Palacio Nacional de Cultura, Managua, February–May 2016

→Casa Fernando Gordillo Gallery, Managua, 1984

→Caribbean Festival of Arts (CARIFESTA), Barbados, July–August 1981

Nicaraguan painter and poet.

June Beer was a pioneering, self-taught Black feminist painter, poet and revolutionary cultural worker from Bluefields, Nicaragua. Born to a working class family and raised by her single mother, J. Beer was the youngest of eleven children and was only able to attend school through the third grade. Despite her short formal education, J. Beer was a prolific reader who cultivated a love of learning from an early age. Throughout the course of her life, she would deeply transgress racialised and gendered expectations of domesticity and respectable femininity that had historically constrained Black women’s lives in Caribbean Nicaragua.

In 1954, J. Beer left her first-born in the care of her mother to find work in Los Angeles. She initially worked as a dry-cleaning attendant and then as an artist’s model. While modelling for various art schools, J. Beer faced unwanted advances and was persistently exoticised. Despite these racialised and gendered challenges, her short-lived modelling career ultimately led her to painting. One night while posing privately for African American actress and activist Ruby Dee (1922-2014), J. Beer expressed that she had a strong feeling she wanted to paint. R. Dee provided her with her first set of art supplies and she immediately got to work on her first painting: a self-portrait of her own nude body. J. Beer’s painterly origin story thus begins with a quest for her own artistic self-making beyond any and all external gazes. J. Beer would continue to meditate on Black and Caribbean Nicaraguan women’s subjectivities in the vibrant, tender portraits that make up the bulk of her painterly oeuvre.

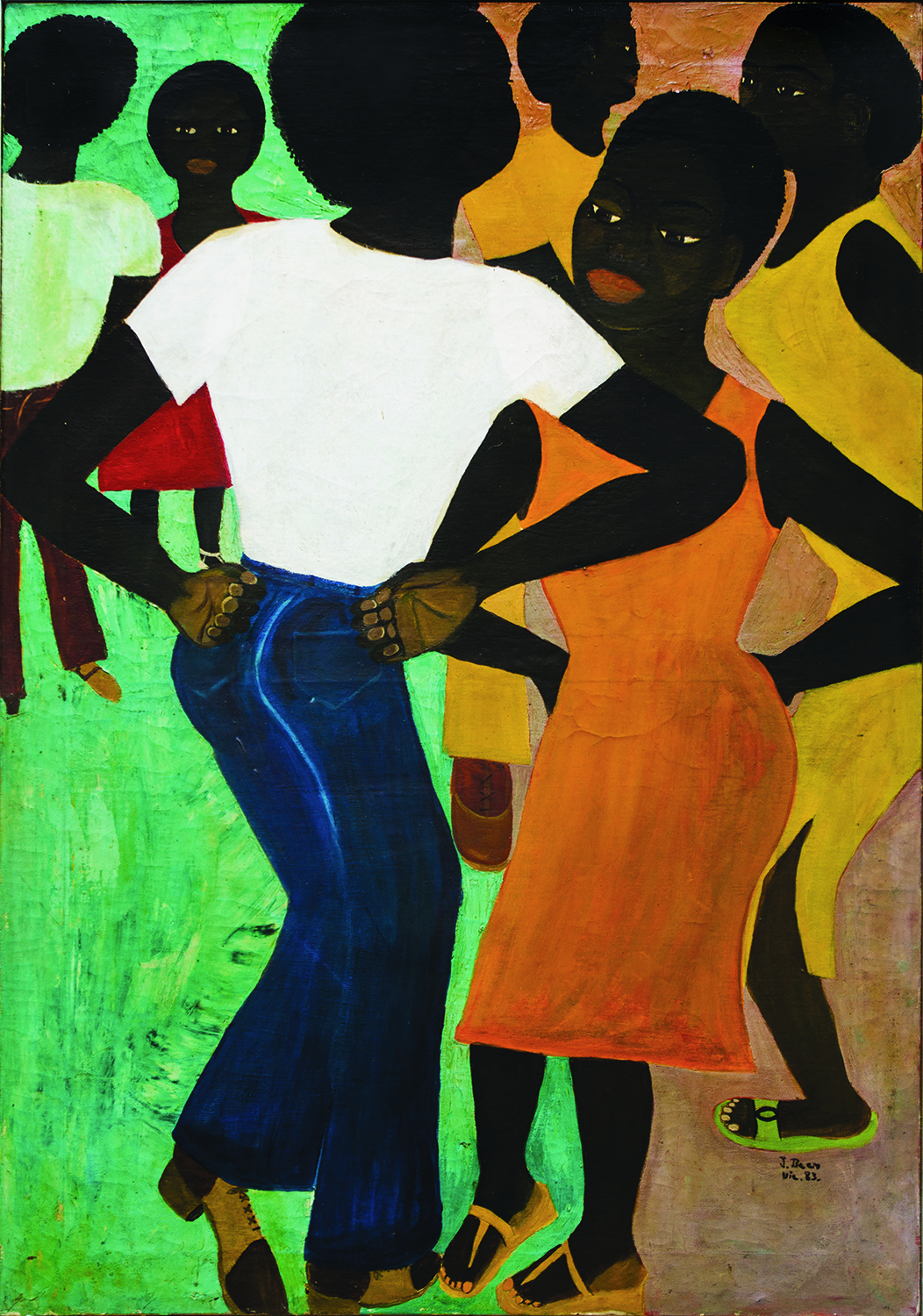

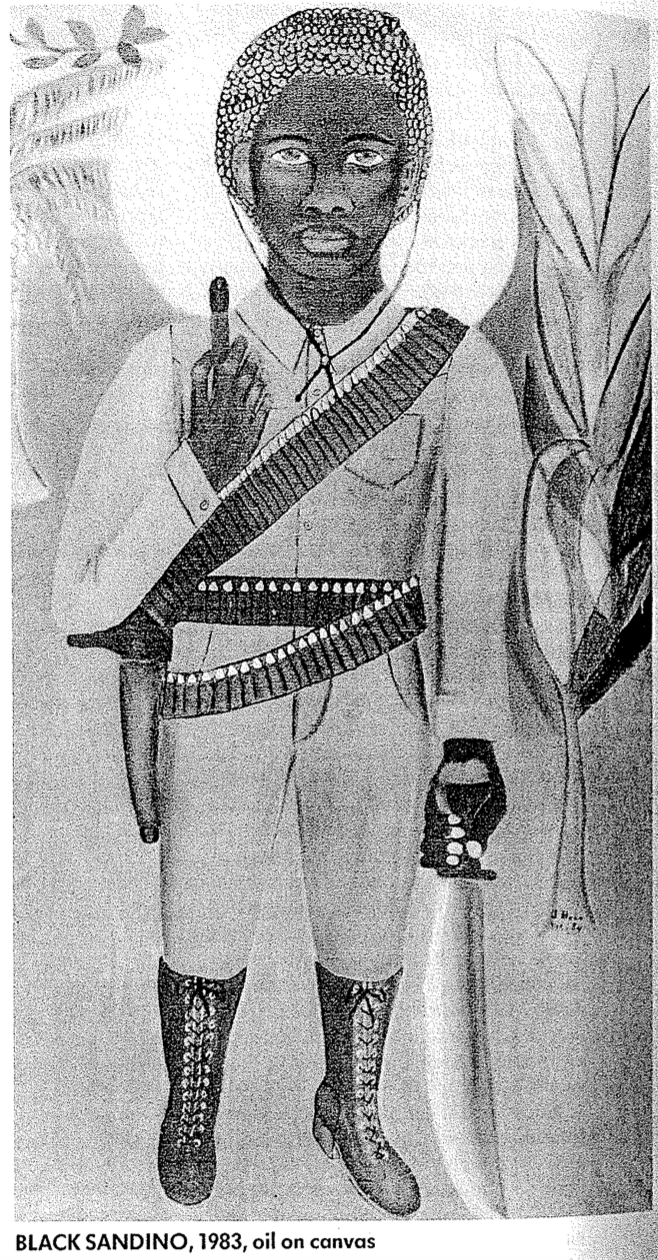

After returning to Bluefields in 1956, J. Beer had three children with a husband who struggled with alcohol use, failed to contribute financially and was unsupportive of her painting. To raise her children, J. Beer collected bottles and plastic containers, sold them to recyclers in Managua, and purchased vegetables with the proceeds for resale in Bluefields. In 1969, she began to travel intermittently to Managua to formally pursue her career as an artist. As J. Beer became immersed in the capital’s revolutionary art circles, her works began to reflect her growing political consciousness. Paintings and poems such as Black Female Militant (1981) and “Love Poem” (1986) not only demonstrated J. Beer’s support for the Sandinista Revolution, but also centred the Black and Indigenous communities of the Caribbean coast as indispensable to the revolutionary process. J. Beer’s work thus presented important criticisms of the revolutionary project’s tendency toward masculinist ethnonationalism.

Following the revolutionary triumph in 1979, J. Beer was appointed as head librarian of the Bluefields Public Library, worked as a contributing editor for the Sandinista newspaper Sunrise and became a member of the Sandinista Association of Cultural Workers (ASTC). With support from the ASTC, J. Beer showcased her work at several national and international exhibitions, including in Barbados, Spain, Mexico, Costa Rica, Cuba, Germany, the Soviet Union, the United States, Italy and Japan. The 2016 Nicaraguan Bienal was dedicated as an homage to J. Beer.

A biography produced as part of “The Origin of Others. Rewriting Art History in the Americas, 19th Century – Today” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023