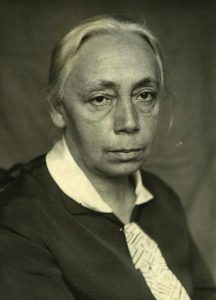

Käthe Kollwitz

Kleberger Ilse, Käthe Kollwitz, eine Biographie, Leipzig, Seemann, 1999

→Martin Fritsch (ed.), Käthe Kollwitz: Selbstbildnisse/Self-Portraits, exh. cat., Käthe Kollwitz-Museum, Berlin (2007), Leipzig, Seemann, 2007

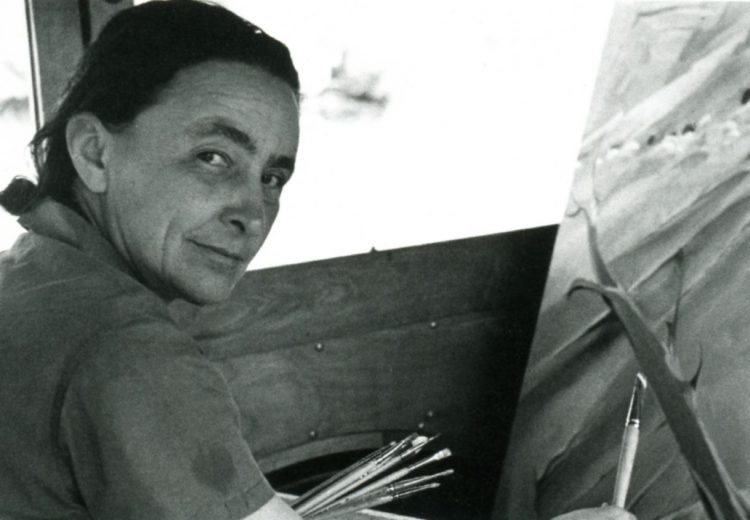

German engraver, draughtswoman and sculptor.

Born into a middle-class family with progressive ideas, Käthe Schmidt was encouraged by her father to follow her wishes and take up painting as a career. From 1881 she learned the fundamentals of copper engraving from Rudolf Mauer in Königsberg, then, in 1885–86, she studied painting from the Swiss Karl Stauffer-Bern in a school for women in Berlin. Later she would attend sculpture courses in the académie Julian in Paris and be awarded a study visit to Florence as the winner of the Romana Prize. But the influence of Stauffer-Bern, who introduced her to the works of the German symbolist painter and engraver Max Klinger, in particular his essay Malerei und Zeichnung [“Painting and drawing”, 1891], convinced her to turn towards drawing and engraving. Klinger’s treatise, which declared that engraving was independent of painting and hailed its effectiveness as a tool for tackling social problems, became an essential text for the young artist. Almost completely self-taught in engraving, she focused her efforts on copper and initially used herself as a model. In 1891 she married the doctor Karl Kollwitz, a member of the German socialist party, who decided to open a clinic in Prenzlauer Berg, a poor district of Berlin, where she was deeply moved by the population’s deprivation.

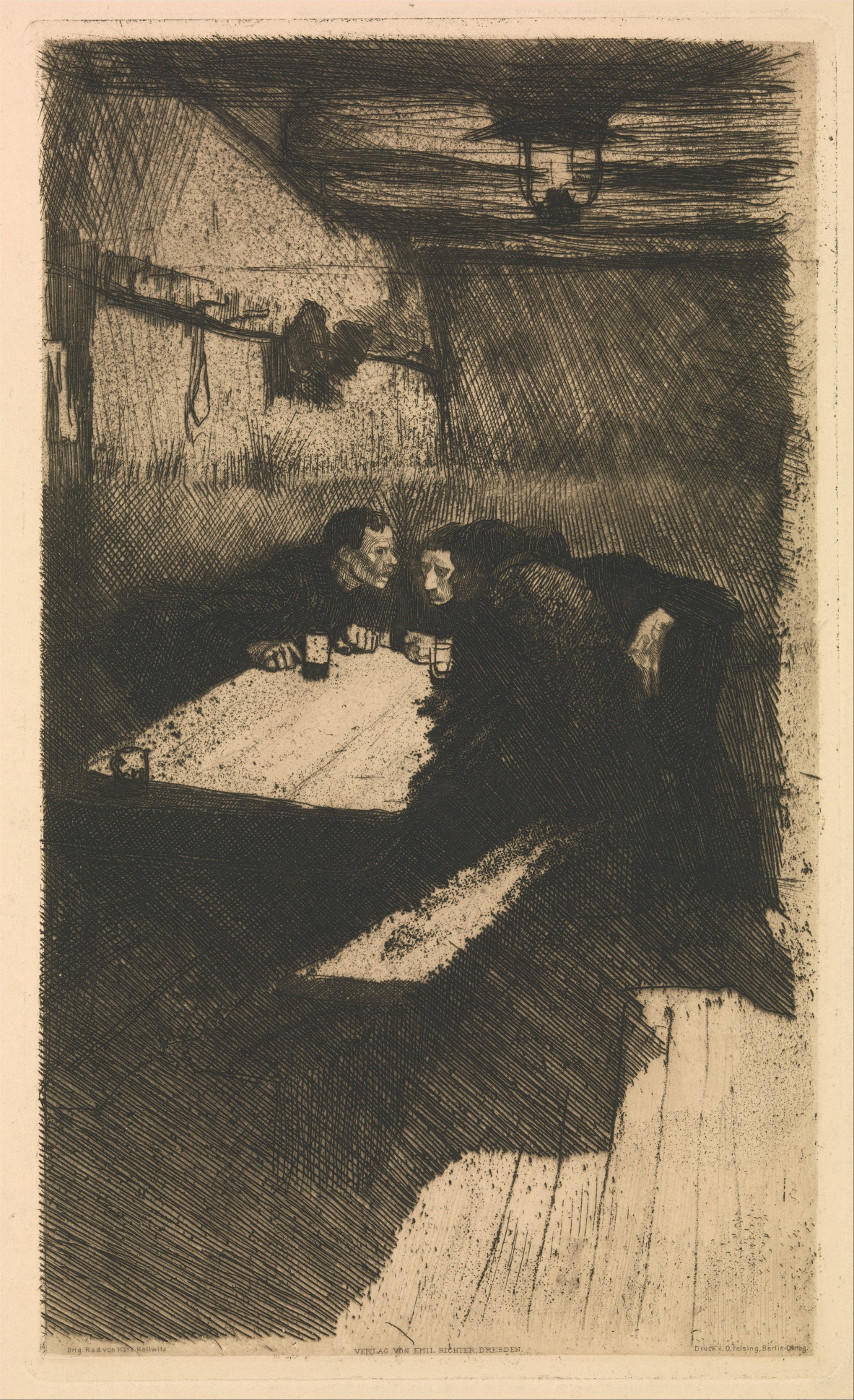

In 1893 she attended the performance of the play Die Weber [The Weavers] by Gerhart Hauptmann, which provided her with the subject of her first series. Between 1893 and 1898 she worked ceaselessly on Ein Weberaufstand [The Revolt of the Weavers], a set of three lithographs and three etchings. When they were presented to the public at the Grosse Berliner Austellung in 1898, the series, which combined deep humanity with a style that is both masterly and accessible on account of its realism, was received to great acclaim. However, the bluntness of the treatment of the bloodily subdued revolt of the exploited weavers did not please the emperor Wilhelm II, who prevented Kollwitz from receiving a medal for her work.

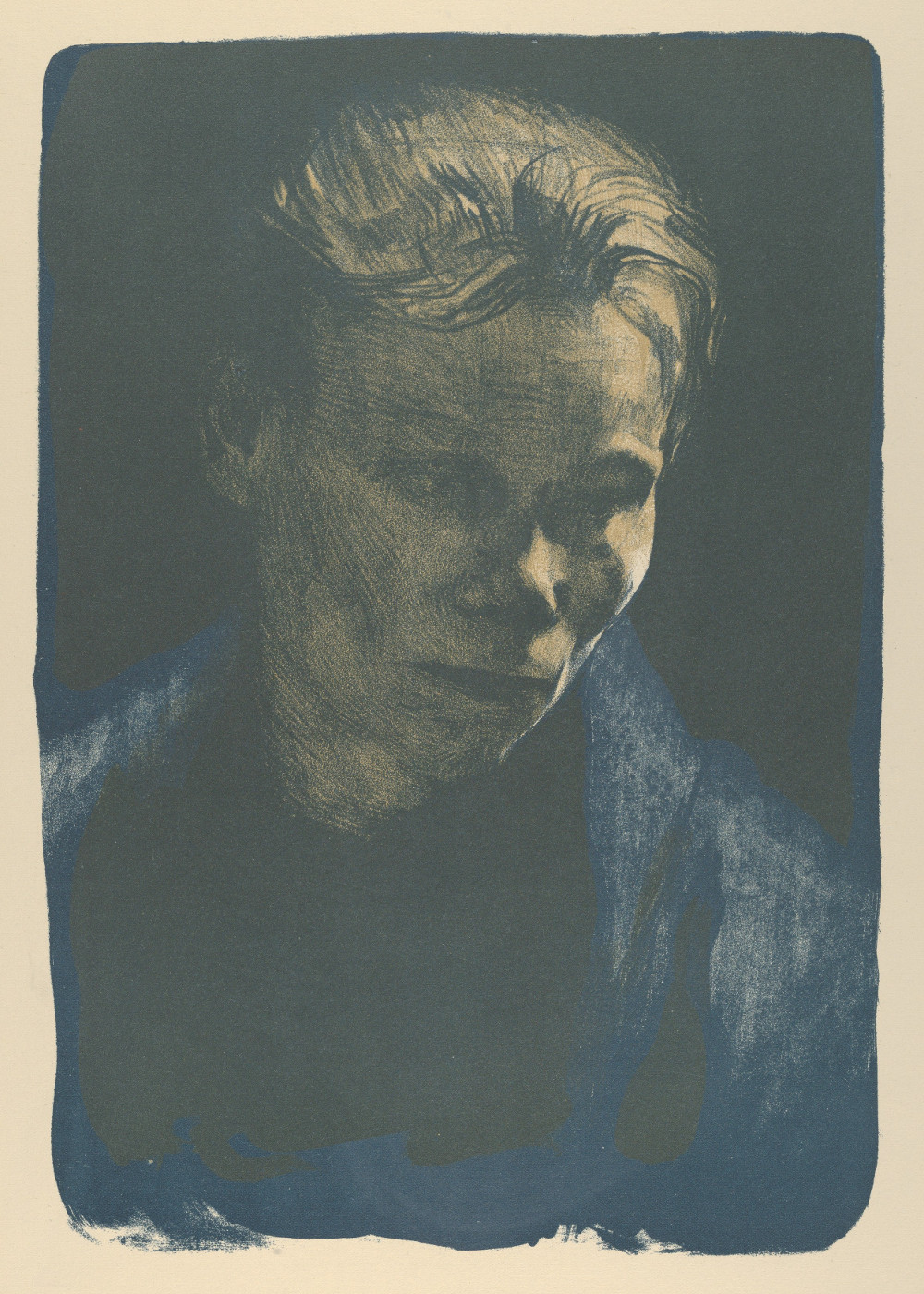

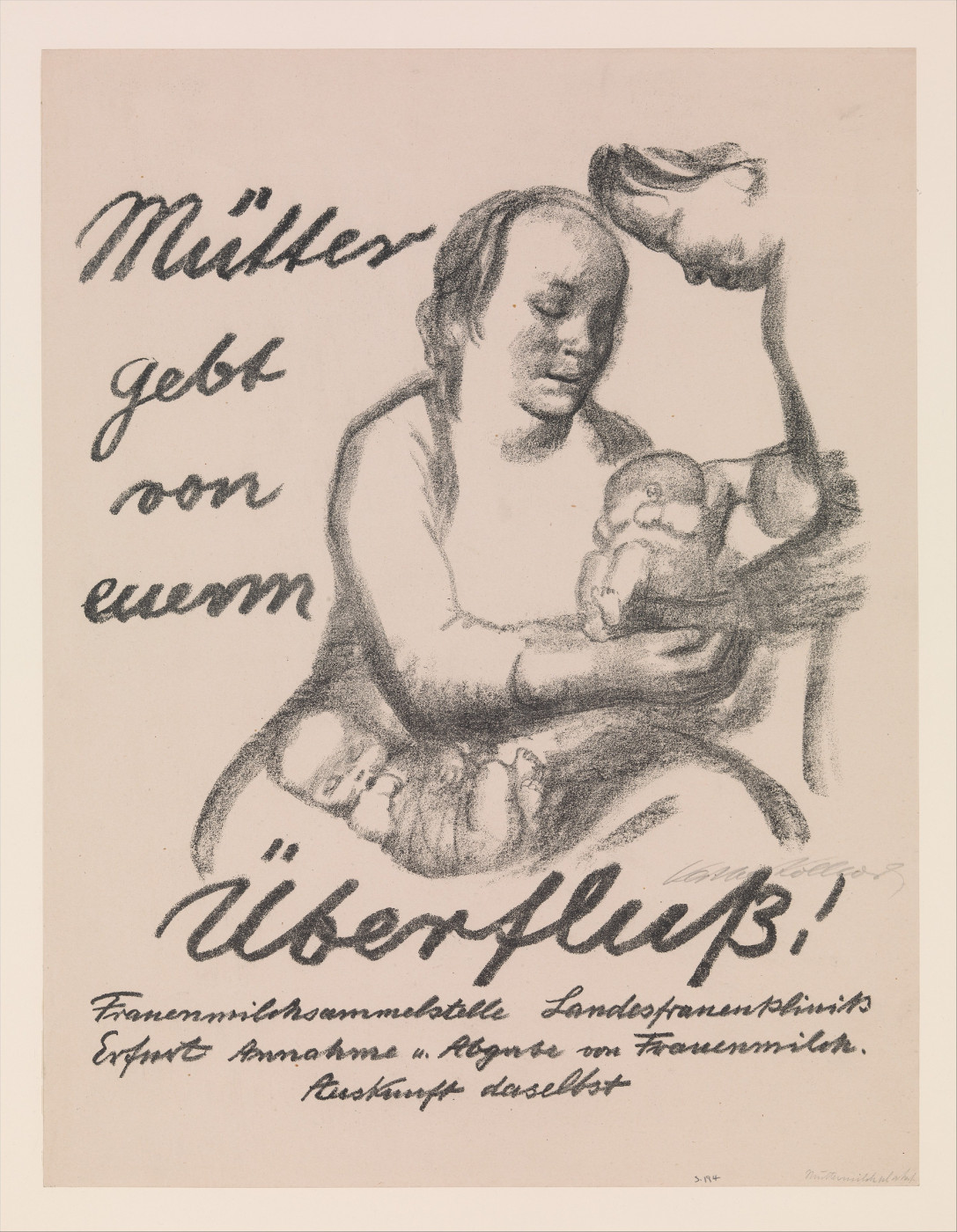

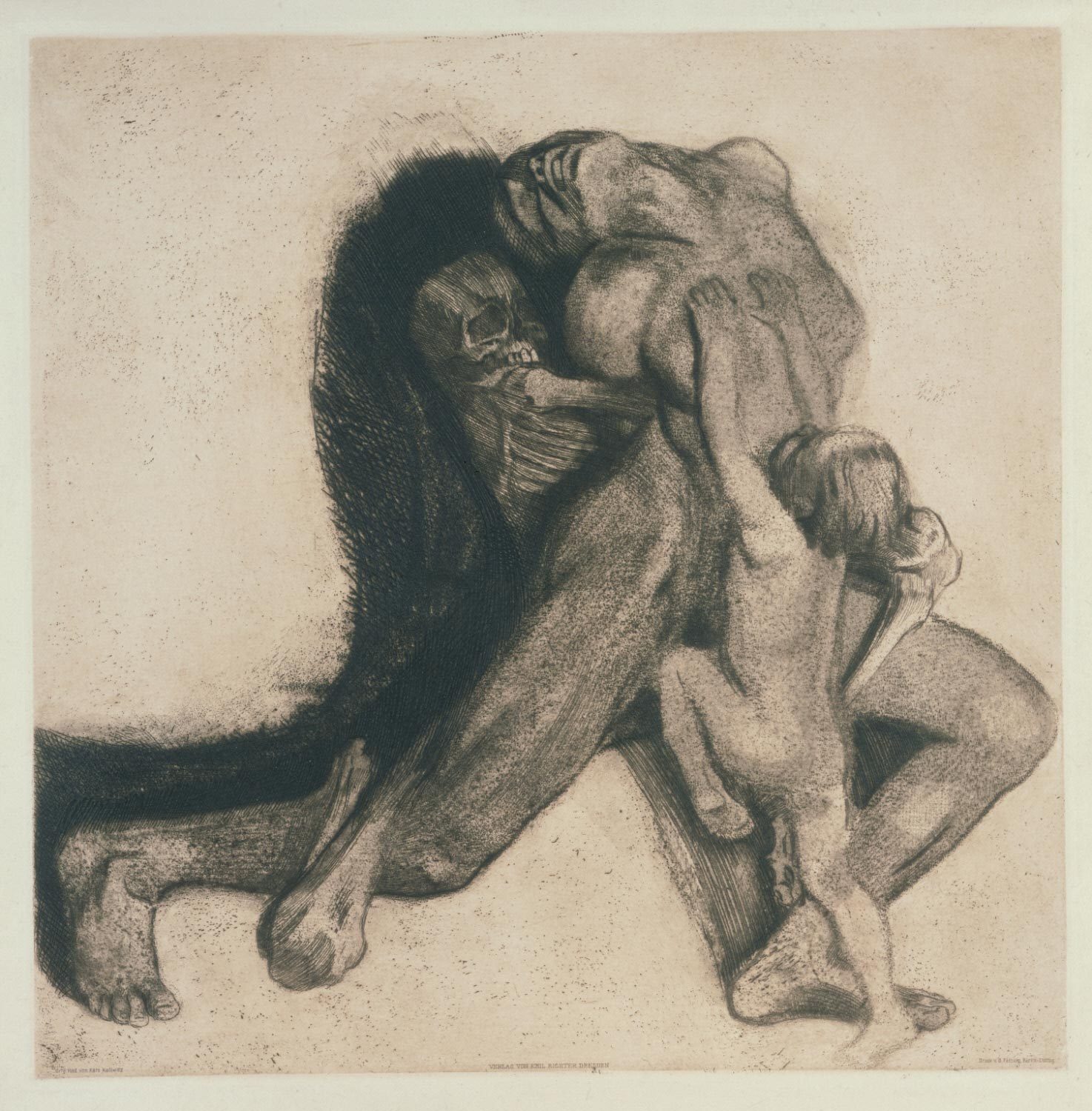

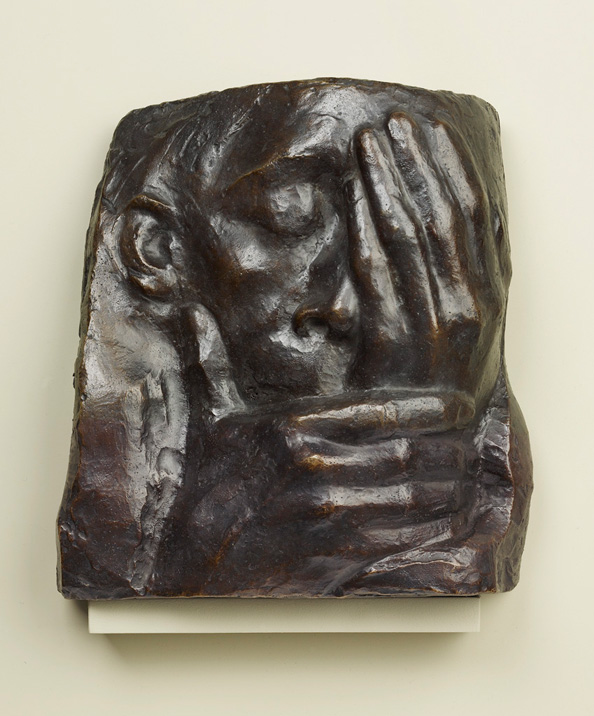

During the years that followed, she progressively turned away from allegorical romanticism in favour of committed realism. Between 1890 and the turn of the century she explored the theme of a mother with a dead child. Some of her works at this time have a power that is almost unbearable. In winter 1901–02 Käthe Kollwitz launched into a second series of engravings, this time on the subject of the Bauernkrieg [The Peasants’ War], which was crushed by force at the time of the Protestant Reformation. She searched for the best framing to communicate the desperation of the peasants in a subject that found echoes in the Germany of the period. When it was presented in 1908, the series was highly successful, whereupon in 1919 she was made the first woman member of the Prussian Academy of Arts and offered a professorship. World War I and the difficult years of the Weimar Republic strengthened her political commitment. She involved herself in many battles, including the struggle for peace. In 1914 Kollwitz’s younger son Peter enrolled as a volunteer and died at the Front, as a result of which her patriotism was replaced by a visceral rejection of war. In 1924 her seven woodcuts Krieg [War] portrayed martyrs of war. In 1928 she was given the post of director of the graphic arts studio at the Prussian Academy but was forced to resign in 1933 for having signed a manifesto to call for unity to defeat the Nazi party in the federal election of 1932. Her In 1934 self-portrait [Selbstbildnis, BnF, Paris, 1934] was made in a telling manner: the close framing puts full emphasis on her haggard face, but her still firm and set mouth seems to be all the more telling due to the fact that she had been forced to remain silent. In 1935 she was no longer permitted to exhibit. During this decade she seemed to return from a sort of inner exile, upon which she turned to sculpture. Evacuated from Berlin in 1943, she settled in Moritzburg as a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony. The attraction of her accessible and humanist art has never diminished: three museums – in Berlin, Cologne and Moritzburg – are devoted to her work.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017