LIANG Baibo

Wangwright, Amanda, The Golden Key: Modern Women Artists and Gender Negotiations in Republican China (1911-1949), Leiden, Brill, 2021

→Caschera, Martina, “Women in Cartoons – Liang Baibo and the Visual Representations of Women in Modern Sketch”, International Journal of Comic Art, vol. 19, no. 2 Fall/Winter 2017

→Libao [Standing Paper], Shanghai, 1935

First Storm Society Exhibition, China Society for the Study of the Arts [Zhonghua Xueyishe], Shanghai, October, 1932

→Storm Society’s Final Exhibition, China Society for the Study of the Arts [Zhonghua Xueyishe], Shanghai, October 1935

Chinese cartoonist and painter.

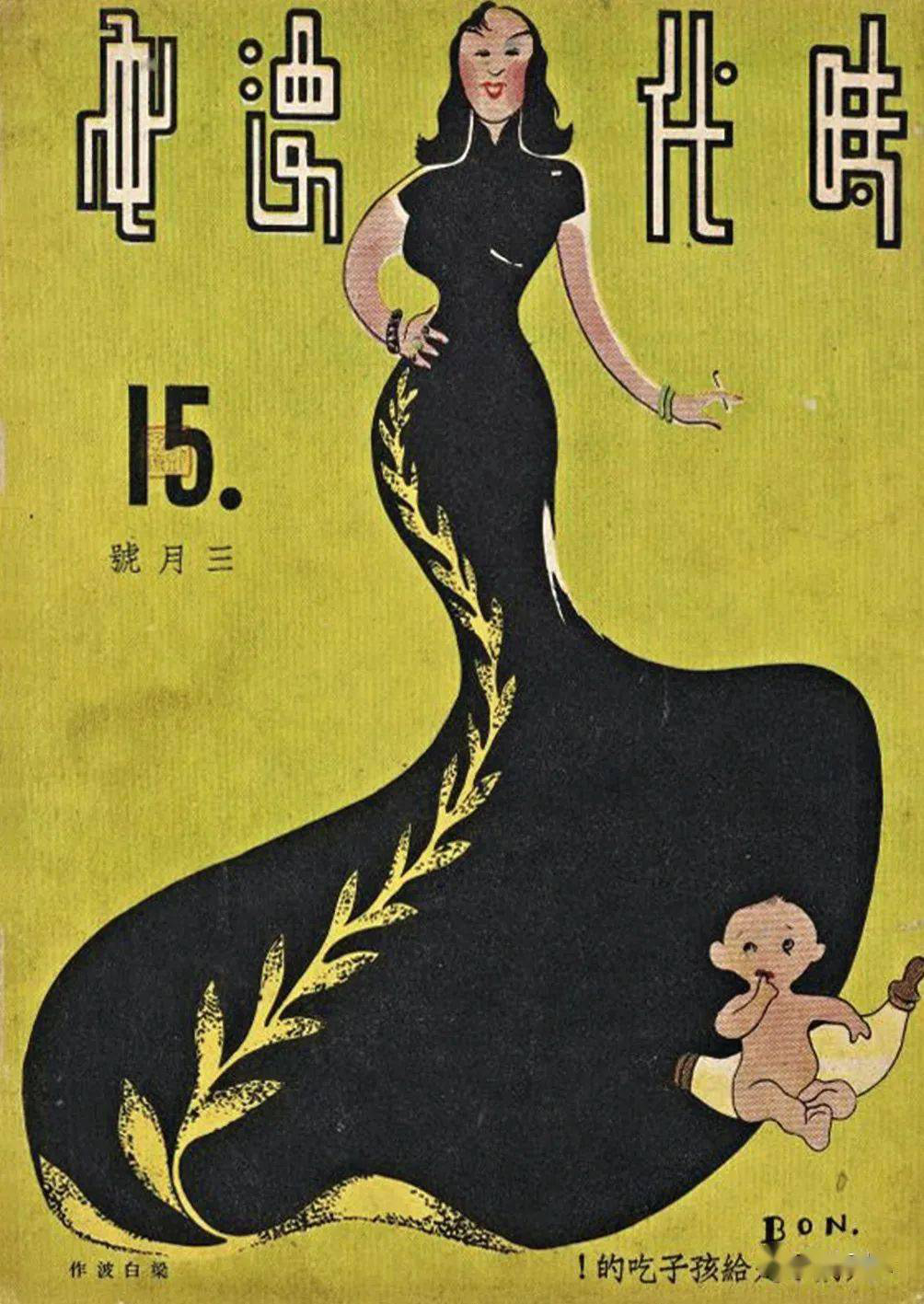

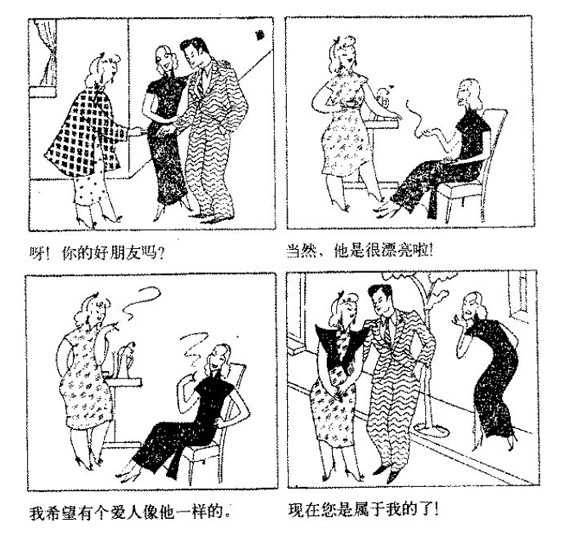

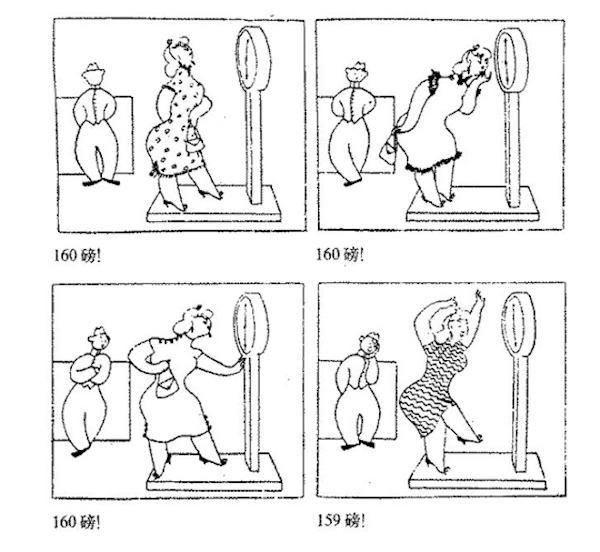

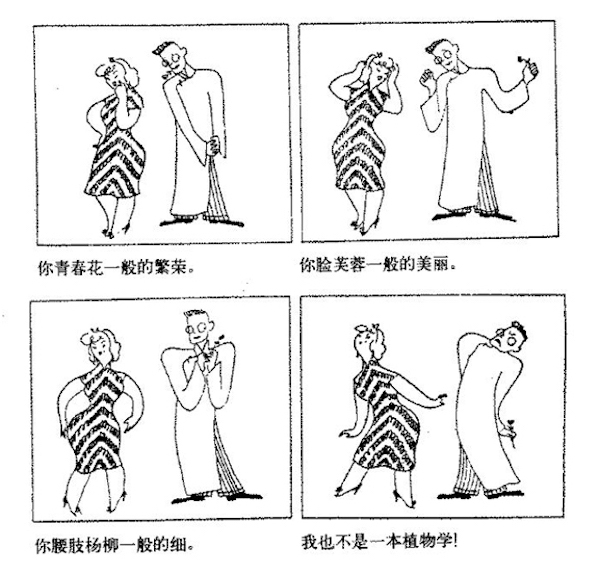

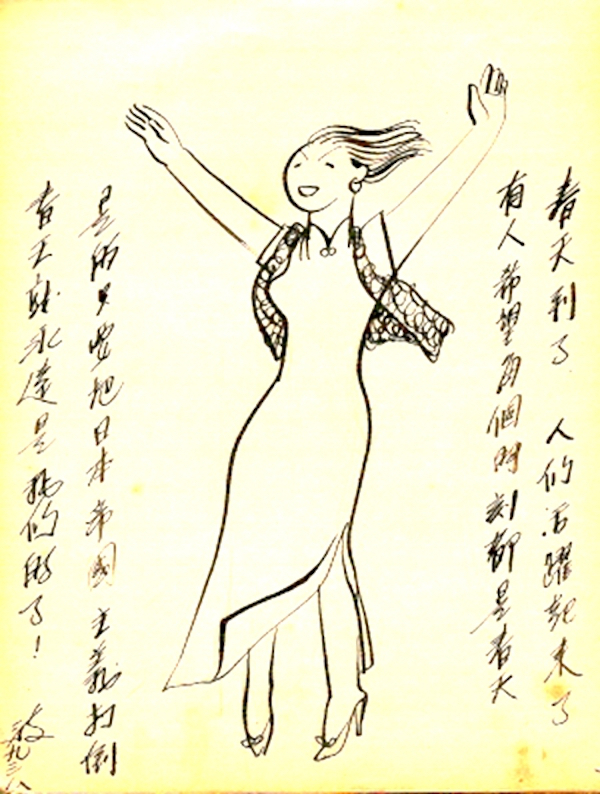

Liang Baibo is recognised as one of the first female cartoonists in Republican China. Liang was born in Shanghai where she studied oil painting at the Shanghai Xinhua Art Academy and the National West Lake Art Academy (now the China Academy of Art). In Shanghai, Liang met renowned Chinese cartoonist Ye Qianyu (1907-1995) with whom she had an affair. Ye was a pioneering manhua [comic] artist and co-founder of the magazine Shanghai manhua [Shanghai Sketch] where Liang would eventually publish some of her works. Under her alias “Zong Bai”, Liang released her most celebrated cartoon Mìfēng xiǎojiě [Miss Bee, 1935] with Ye. Miss Bee reflects the growing women’s rights consciousness during the women’s liberation movement in Shanghai. The character personifies the “Modern-Girl” and “New Woman” that were seen as representations of new womanhood at the time. Liang’s activism extended far beyond the confines of the groups in which she was a member, including the Storm Society [Juelanshe], Société des Deux Mondes [Taimeng Huahui] and the Communist Youth League, where she created covers for numerous magazines, illustrations in poetry collections and children’s books.

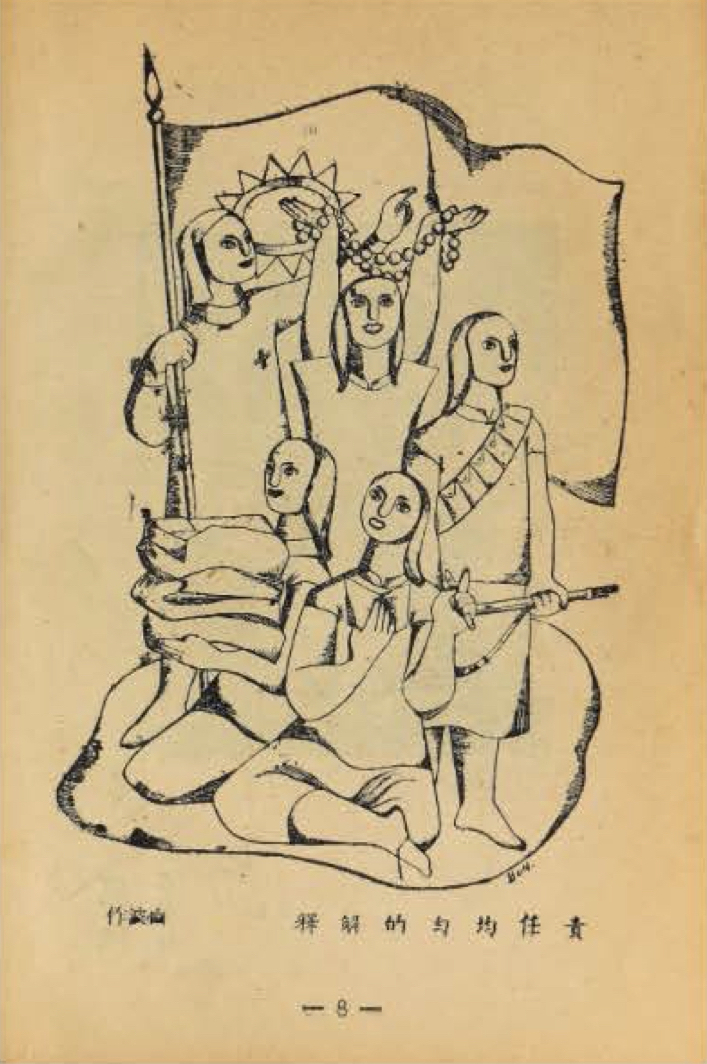

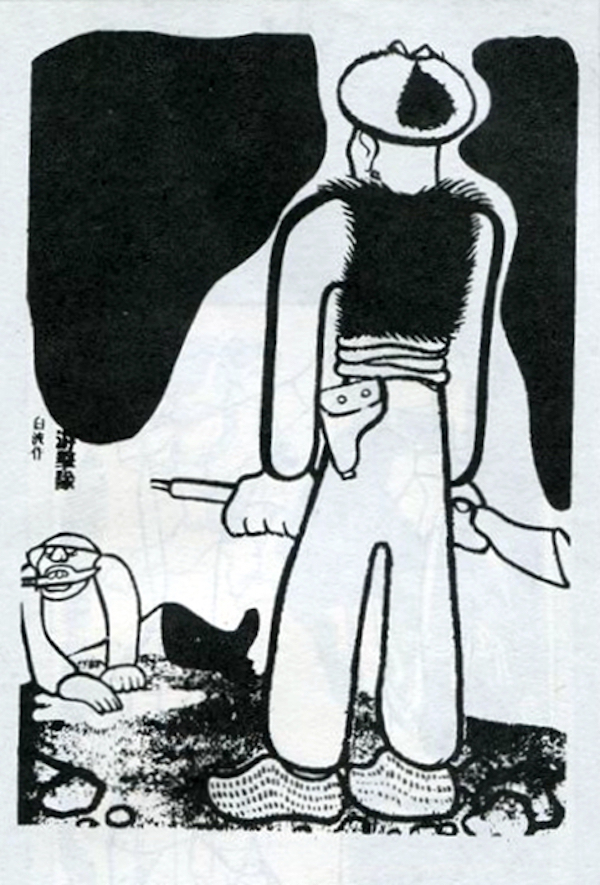

Comics like Zeren junyun de jieshi [An Explanation of Even Responsibility] published in 1938, demonstrated the important role that women played during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) when women’s involvement became crucial to the success in battles. Showing women as teachers, nurses and soldiers, Liang portrays a sense of unity and camaraderie among the group. This is a dramatic shift from the portrayal of her earlier character, Miss Bee, who was lavishly styled, but the rather plain appearance of the wartime women acts as a commentary on the differing perceptions of women during this time. Liang was the only female member of the National Salvation Cartoon Propaganda Corps, whose mission was to spread anti-Japanese literature and art following the Japanese invasion of China. Through posters, cartoon exhibitions and painted murals, the group promoted national pride to boost morale. Their impact was the most invaluable in areas of the country where the literacy rates were low, and the citizens relied on visual imagery for comprehension. By 1938 Liang had left the group and her artistic career fades into obscurity. A few of her works were even mistakenly published under Ye’s name. In her later years she returned to painting, drawing and watercolours, though few of her works survived from this period. Liang went on to marry a pilot in the Republic of China Air Force and they moved to Tibet during the war only to return to Shanghai following Japan’s surrender in 1945. When the Communist Party began its rise to power, however, Liang and her husband, along with their young son, moved to Taiwan and it is suspected that she died by suicide in the late 1960s.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023