Louise Nevelson

Celant Germano, Louise Nevelson, Milan, Skira, 2012

→MacKown Diana, Aubes et crépuscules : conversations enregistrées avec Diana MacKown, Paris, Des Femmes, 1983

→Wilson Laurie, Louise Nevelson: Iconography and Sources, New York, Garland Pub, 1981

Louise Nevelson, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 1967

→The Sculpture of Louise Nevelson: Constructing a Legend, exh. cat., Jewish Museum, New York, 5 May–16 September 2007

→Louise Nevelson, Centre National d’Art Contemporain, Paris, 9 April–13 May 1974

American sculptor.

“I want to be sculptor and I don’t want color to help me”, declared, while still a child, the woman who, throughout her life, would occupy space with her massive and poetic sculptures. Of Russian origin and Jewish tradition, her family emigrated in 1905 to the United States, where Louise Nevelson received a twofold legacy: the free-thinking climate advocating equality between the sexes in which she was raised, and craftsmanship—her grandfather was a timber merchant and her father worked in a factory dealing in the same material—, which she would subsequently have a preference for. In 1920 she married and settled in New York, where she could devote herself to her passions: painting, dance, singing, piano and theatre. In 1931, divorced, she went to Europe on her own, where she further developed her knowledge of Cubism with her teacher, Hans Hofmann (1880-1966), in Munich, as well as the “primitive arts”, in particular at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, where she discovered African art. Back in New York, she became the assistant of the Mexican painter Diego Rivera (1886-1957), who produced a series of frescoes for the New Workers School. At the Art Students League, she took Hofmann’s classes once again, but also those given by the German artist George Grosz (1893-1959). In the same period, she showed her first paintings and her anthropomorphic sculptures. In the 1940s, in addition to her first solo show at the Nierendorf Gallery in New York, Nevelson started engraving, a technique which she would practice for the rest of her life. Under the influence of Cubism and “primitive art”, she moved away from traditional sculpture and produced assemblages, devised using found pieces of wood. During the 1950s—this was a pivotal moment for her—, her visits to the archaeological sites and the vision she had of the façades of pre-Colombian buildings in Mexico inspired her to create environments made up of several elements juxtaposed in space.

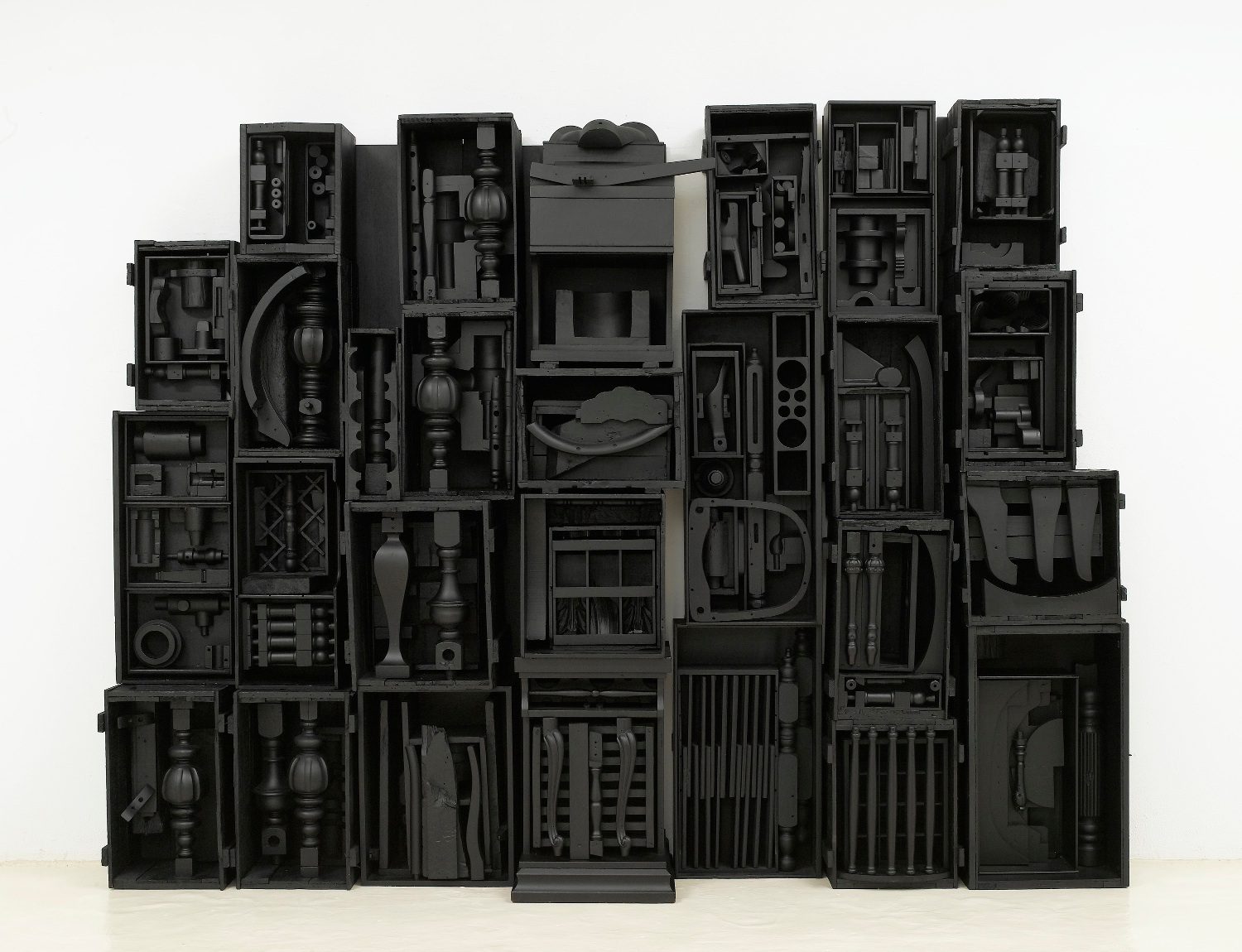

Her sculptures then became akin to walls, large painted wooden constructions, or ensembles formed by strictly geometric structures, in the manner of Tropical Garden II (1957); they were covered with a single colour, matt black or gold, unifying everything and camouflaging the primary identity of the different pieces. This determinedly abstract artist was also influenced by theatre and dance, which she was involved in at a very early age. Her sculptures swiftly took on a dynamic character and were set in motion, like her Moving-Static-Moving-Figures. In addition to her presentation in Europe at the Jeanne Bucher gallery in Paris, the year 1958 represented a turning-point in her career with the show Moon Garden + One at the Grand Central Moderns gallery in New York: huge crates, with variable geometry, filled with retrieved objects, all black, were piled up to form wall sculptures akin to bas-reliefs, which gave the space a dynamic feel. In 1959, she exhibited her first environment using white totemic figures, Dawn’s Wedding Feast, dealing with the theme of marriage, which was recurrent in her work; by experimenting with many different techniques and materials, she would continue producing her “monster knick-knacks”, as the artist Jean Arp (1886-1966) called them, after discovering Sky Cathedral (1958). In 1966, she used aluminum to make her first metal sculptures, then, in 1967, she produced small works in plexiglas. She responded to various monumental commissions and created one of her first Cor-ten steel ensembles, Atmospheres and Environment X (1969) for Princeton University, followed by Night Presence IV (1972) in New York. As a recognized figure in the American art scene, Nevelson was chosen, in 1962, to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale and, two years later, she exhibited at the Kassel documenta. Several retrospectives of her work were held. In 1979 she was elected a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. To mark her 80th birthday, the Whitney Museum held the exhibition Atmsopheres and Environments. This artist, who defies pigeonholing, and whose works are held in all the great international collections, played a leading role in the history of modern sculpture in the United States.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Louise Nevelson, “New York Is My Mirror”

Louise Nevelson, “New York Is My Mirror”