Marianne Berenhaut

Marianne Berenhaut. De bon cœur / De Bunker, exh. cat., Recklinghausen, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen (27 August-12 November 2023).

→Melzacka Alicja, Marianne Berenhaut, Mine de Rien, exh.cat. CIAP and C-mine (23 October 2021 – 16 January 2022, Ghent, Belgium, 2022

→Marianne Berenhaut, Conversation avec Nadine Plateau, Editions Tandem, 2018

→Thierry de Duve, “Vie Privée,” in Marianne Berenhaut: Sculptures, exh. cat. Centre d’Art Nicolas de Staël, 2003.

Marianne Berenhaut—endroit anvers, M HKA, Antwerp, 11 September 2021–9 January 2022

→Marianne Berenhaut, Mine de rien, CIAP/ Jester and C-mine, Ghent, 23 October 2021–16 January 2022

→Marianne Berenhaut, De bon Coeur / De Bunker, Kunsthalle Recklinghausen 27 August 2023–12 November 2023.

Belgian sculptor, drawer and visual artist.

In her art, Marianne Berenhaut gives us a unique perspective on the world through the critical lens of a woman who as a child, together with her twin brother, grew up hidden away in a Catholic orphanage during the Shoah. Her work speaks of the harm, the damage and the scars that remain as a tracery through society: the marks of longing and loss, disquieting absurdity and trauma, unbidden hilarity and memory.

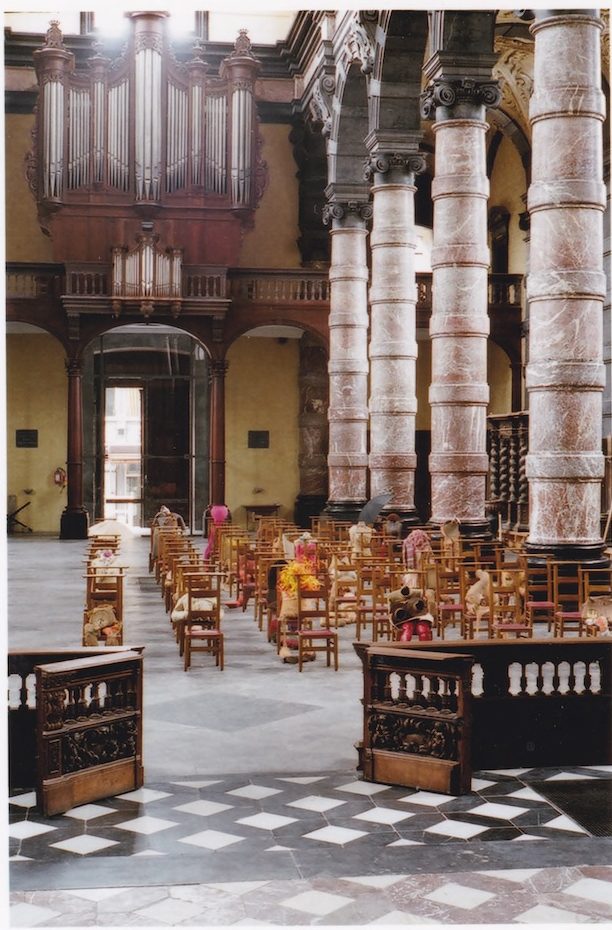

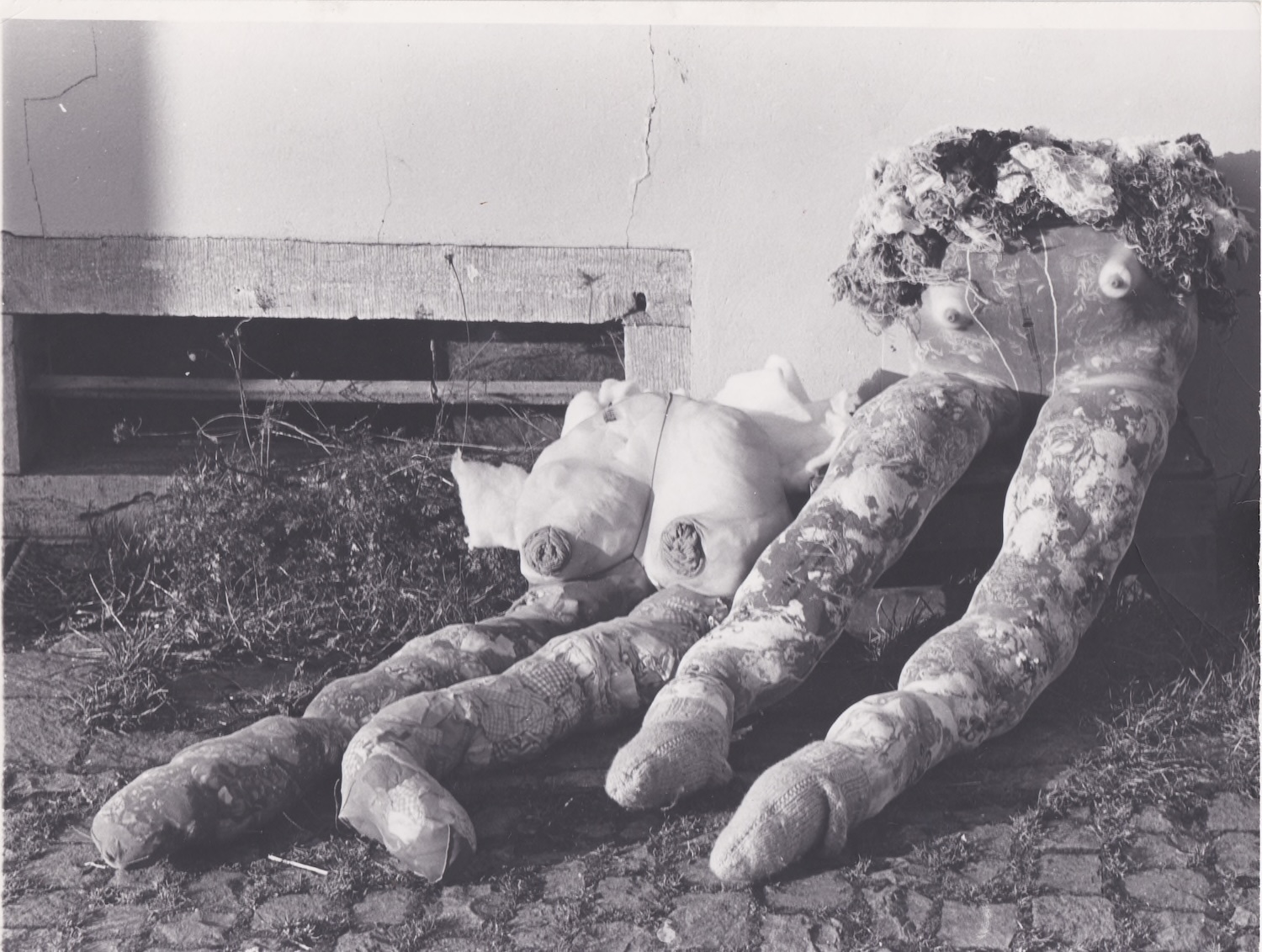

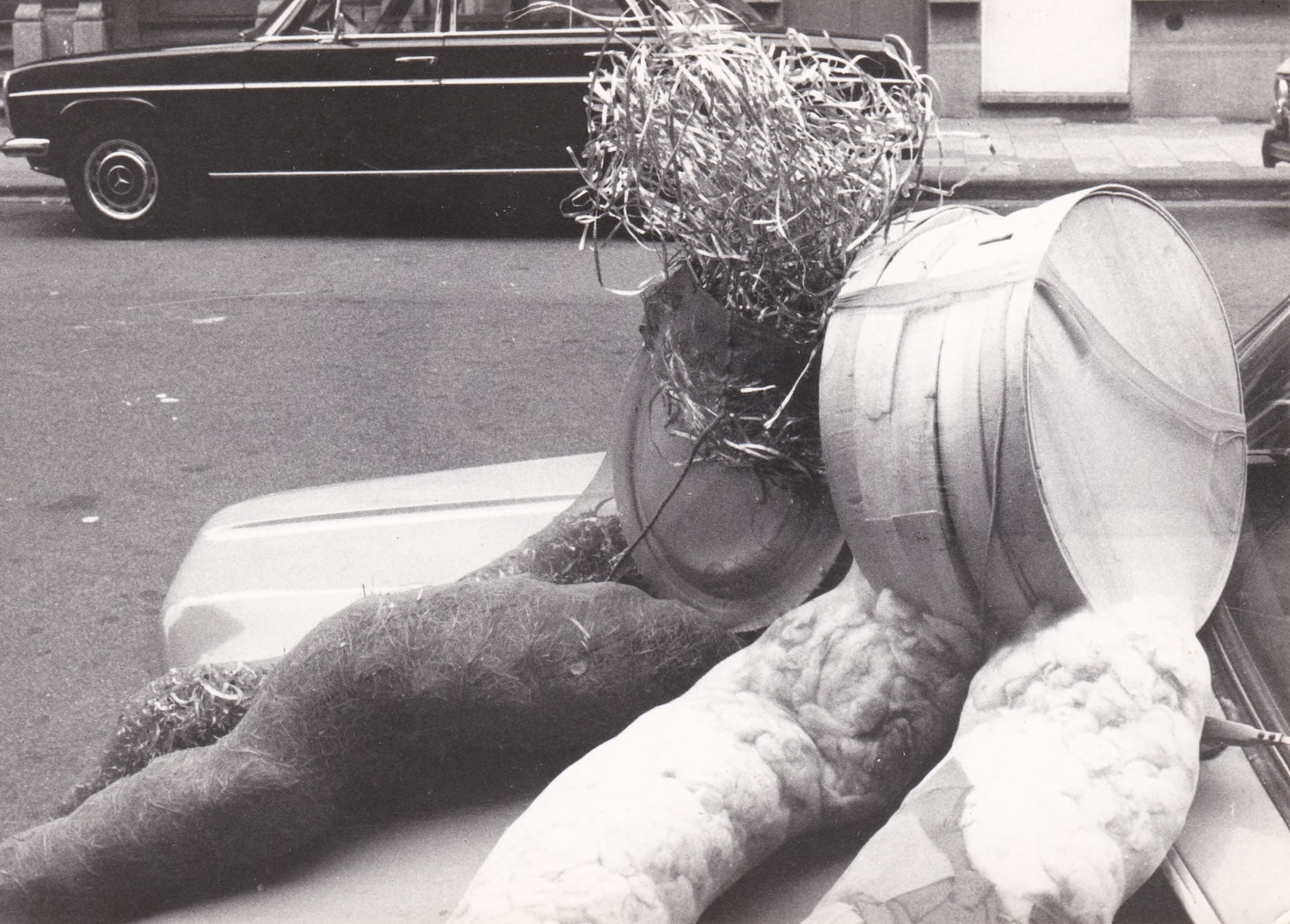

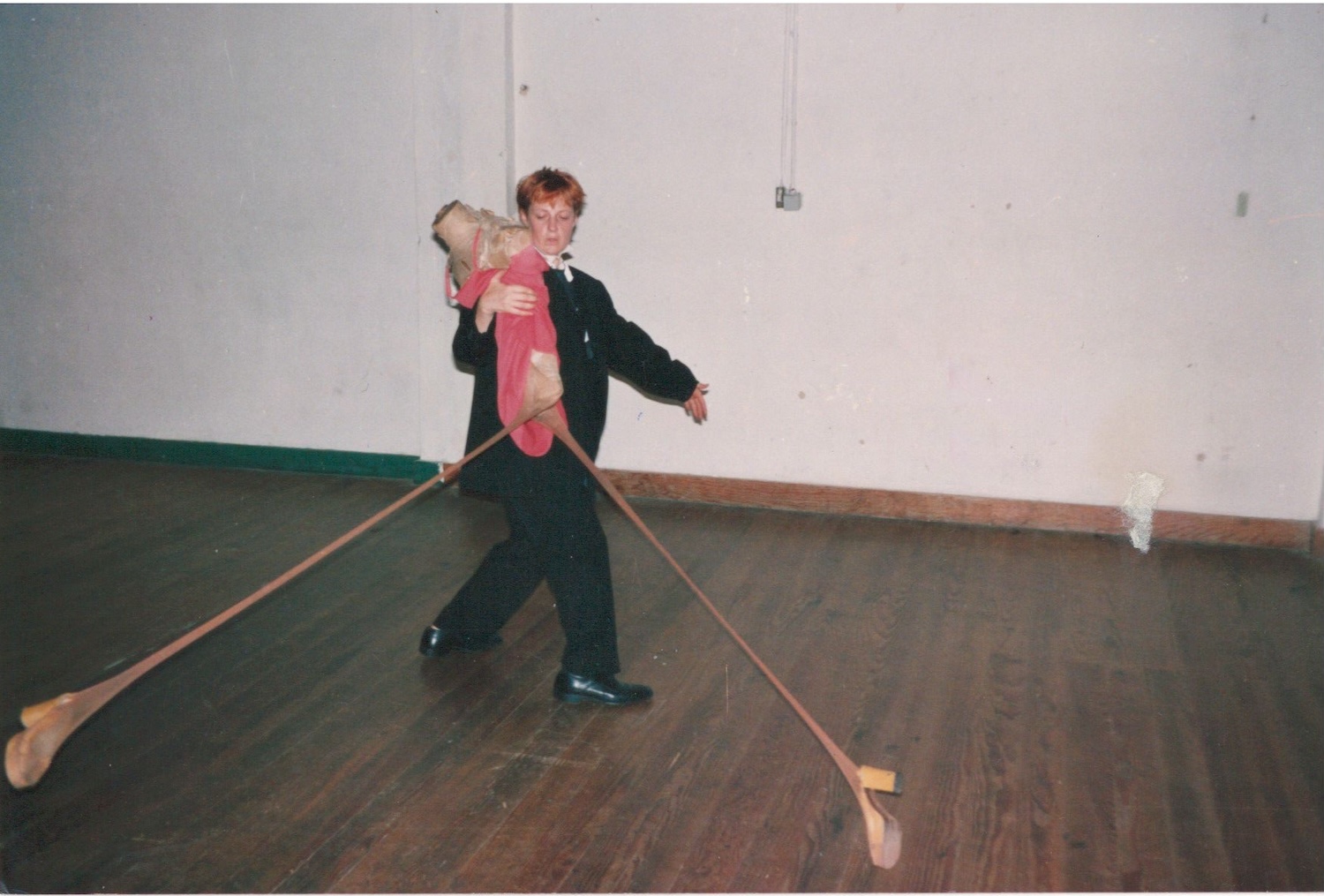

In the 1960s she graduated at the Académie du Midi and Atelier of Jacques Moeschal (1913-2004) in Brussels. Her inimitable visual language, in which creation and survival are intricately entwined, is first evident in her sculptural constructions of plaster and wire, made as if attempting to heal the household void left by the wounds of war: Maisons-Sculptures (1964-1969). Of this series only archival photographs survive. The Poupées-Poubelles (1970-1979; and ongoing) follow, made of remnants of soft discarded fabrics and materials, making them sensual. They very much remind us of the fragmented body as in Melanie Klein’s theory of the part-object, a conception further developed by Donald Winnicott as the transitional object. In her landmark work, the Poupées-Poubelles form a highly significant sculptural group of haphazardly assembled, stuffed “trash dolls” whose unruly organs and limp limbs are disjointed. Holding the figures together, just about, is the gossamer filament of pantyhose, a perfectly ambiguous material for feminist artists. Notably, once 49 dolls, seated on chairs, were installed in the church of Saint-Loup in Namur (2008). These models like worn-out cuddles are deformed and twisted: thing-bodies, padded and damaged bodies.

As a survivor of the Shoah, M. Berenhaut seems to have a fascination with, even an affection for, the abject body, the marginal body that doesn’t fit, the body that is a mishmash, the body that is defective, battered, eviscerated and torn – a fodder with everything and anything – a fascination for the body that triumphs over everything, the body-belly, the headless, faceless body, the object body. Seen together, the Poupées-Poubelles convey the image of collective violence, degradation and destruction but at the same time there emanates from this chaotic scrambling an ironical amusement and ambivalence born of the everyday of domestic life. Some dolls contain found utensils and salvaged objects: an accordion, a strainer, needlework, a broken clock or a perforated umbrella; others consist of bright pink or turquois leftovers of clothing – materials the artist has collected on the street or daily gathered from the world around her and transformed into powerful yet fragile sculptures and evocative installations. To quote M. Berenhaut: “When I look at the Poupées-Poubelles, I don’t feel upset. There is a mirror effect: I am, piece by piece. I am coming out of every pore. I am penetrated, invaded, dispossessed. And yet, in this thin skin, I am growing, I am living.”

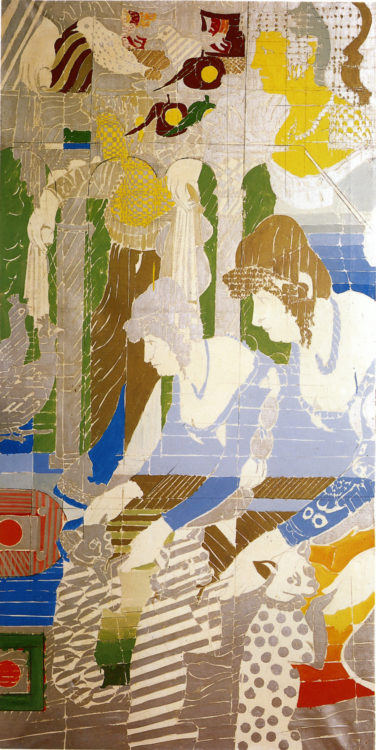

Alongside her sculptures, M. Berenhaut continues her drawing practice in the Cahiers-Collages. From 1980-2000, she experimented with staging objects, furniture and clothing in small configurations or large-scale installations composed of a myriad of retrieved things. The series is titled Vie Privée, and again points to abandonment and desperation but also eloquently to the domestic and motherhood – “a true archaeology of the quotidian”. Since 2015, her poetic oeuvre has continued opening up to a greater sense of intimacy, of jouissance and playfulness, with humor and a dose of surrealism have always been present in her works: Bits and Pieces (2020).

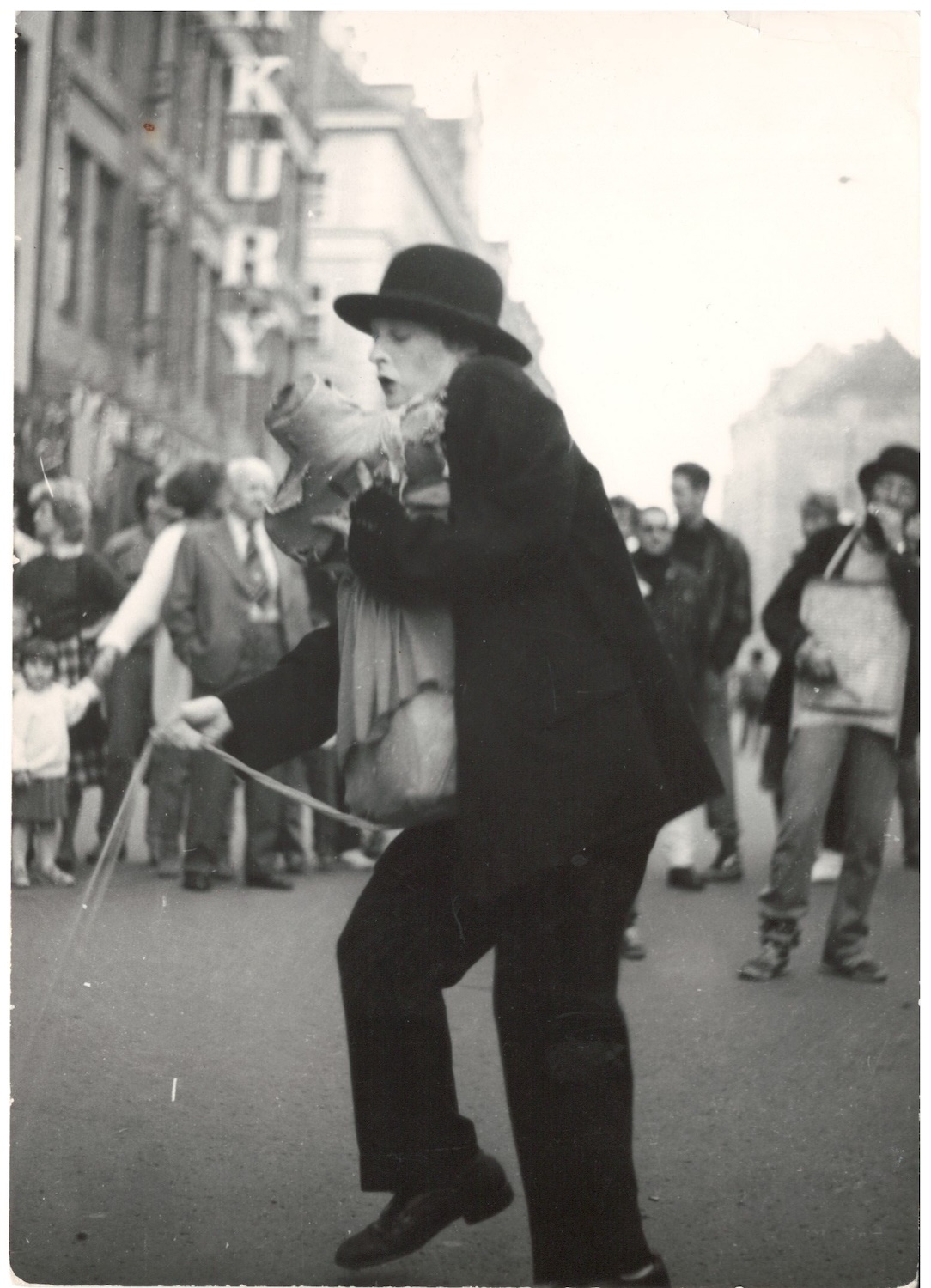

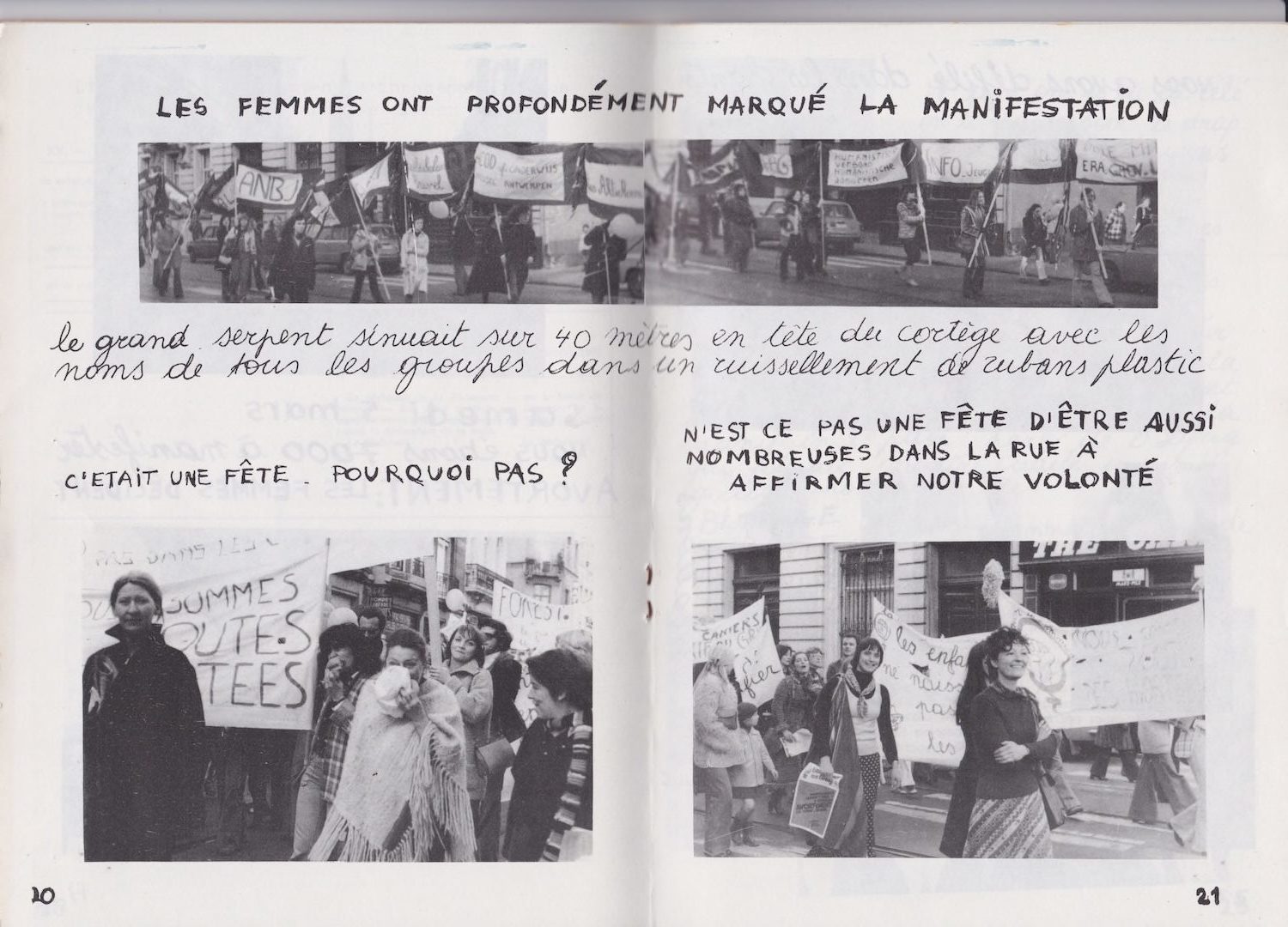

Regarded by some as a Grande dame of Belgian art, M. Berenhaut has largely worked outside institutional contexts, beginning with in feminist demonstrations in the 1970s but also touring with theatre groups, and performing in the street and public parks. Recently, although her body of work spans over six decades, there is renewed interest in her mesmerising oeuvre with important solo exhibitions and retrospectives at M HKA in Antwerp and at the Kunsthalle Recklinghausen. M. Berenhaut’s art can also be seen in the collections of the FRAC Grand Large – Hauts-de-France and of the Museum of the Jewish People in Israel. At the age of 90, her work is more vivid and witty than ever.

Marianne Berenhaut - exposition Vie privée au MACS, grand Cornu, 2007

Marianne Berenhaut - exposition Vie privée au MACS, grand Cornu, 2007