Review

Exhibition view of Alina Szapocznikow Human Landscapes at the Hepworth Wakefield, Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield, © Photo: Lewis Ronald

Does the importance of Alina Szapocznikow’s place in the history of art still need to be demonstrated?

The work of this important polish artist have allowed for the reappraisal in the current context thank to the large Sculpture Undone1 retrospective, presented in particular at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), and the Du dessin à la sculpture2, exhibition at the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou (Paris), yet the interpretation of her work is far from complete. The substantial exhibition organised by Marta Dziewańska and Andrew Bonacina at the Hepworth Wakefield (United Kingdom) contributes marvellously to reminding us how much this artist’s work remains enigmatic and yet essential to the understand of post-Second World War art.

Exhibition view of Alina Szapocznikow Human Landscapes at the Hepworth Wakefield, Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield, © Photo: Lewis Ronald

The selection opens with a major work: the first version of Noga [Leg, 1962], a plaster model of the artist’s lower limb3. This sculpture embodies the change in direction that Alina Szapocznikow took from socialist realism (Staline in 1953) to radical experimentation, whilst asserting her knowledge of traditional practices and materials. She highlights the artist’s engagement in respect of introspection, thus paying a tribute to surrealisms and their links with psychoanalysis, as well as to the appropriation of her body and her social representation, with an irremediably protofeminist approach. Noga is exhibited next to the works of the museum’s permanent collection, which comprises numerous pieces by Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, thus favouring a fascinating dialogue with these two sculptors, from a visual, historical and intellectual point of view.

The visit continues with the disintegration of the body initiated by Alina Szapocznikow as of the 1950s, starting with Premier Amour (1954) – it is not specified that this piece was exhibited at the Musée Rodin in Paris as of 1956 –, continuing on to Ekshumowany (Exhumé, 1957). This sculpture, by presenting a body that is decomposed and deformed, like a thinker by Auguste Rodin rising after a session of torture or the explosion of an atom bomb, demonstrates the difficulty as well as the necessity of surviving trauma. The trauma that is identified here, and which is both biographical and historical, is that of the Second World War and the Holocaust. However, it can also be expanded to the treatment of certain members of the opposition in communist Poland. What is human is sometimes transformed, becoming a monstrous Monstrum II (1957) and Philosophe (1965), amputated.

Exhibition view of Alina Szapocznikow Human Landscapes at the Hepworth Wakefield, Courtesy The Hepworth Wakefield, © Photo: Lewis Ronald

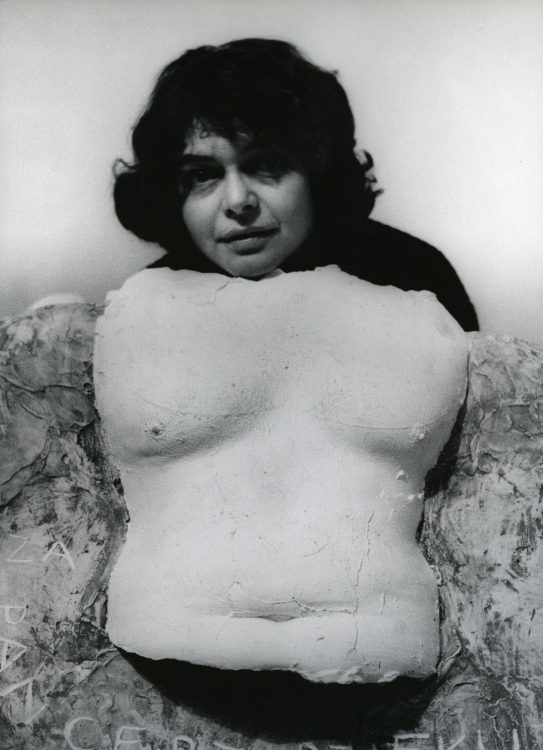

When the artist settled in France permanently as of 1963, the assertive appearance of industrial objects in her sculptures commenced, along with the use of new materials, polymers, sometimes developed with the help of a chemical engineer from Rhône-Poulenc. Her interactions with New Realism, through Pierre Restany4, are extremely fruitful. La Machine en chair (1963-1964) is a vivid demonstration in this domain, even if it is regrettable that the sculpture Goldfinger (1965) is only exhibited as a photograph, the latter having got the artist noticed by Marcel Duchamp and Jean Arp and having won the Copley Foundation award in 1966. As regards photography, one of the more interesting sides to the exhibition is that it demonstrates the polymorphic work links the artist had with this medium: archive photographs, photographs integrated in her sculptures (Tumeurs, Enterrement d’Alina), Photosculptures (1971), created in collaboration with her second husband, Roman Cieslewicz, etc.

Alina Szapocznikow’s presence in France also marks the beginning of a playful and courageous exploration of her erotic imagination. The room, which is lit in the style of a chapelle ardente and which, amongst others, brings together her, Lampes-Seins and Lampes-Bouches as well as Femme illuminée (1966-1967), pays tribute to the work’s seductive nature whilst recalling, with the exhibition of Rolls Royce (1970), her extreme thoroughness and her design aspirations.

The constant frictions between Eros and Thanatos revealed by Alina Szapocznikow’s work are at the heart of an important series on display in the last room: Tumeurs, Herbier or Paysages humains (from which the exhibition’s title is taken). This last part of the selection, which forms the apotheosis, bears witness to the artist’s engagement to conserve the significant traces of man’s passing; transient, fragile, imperfect traces, but in spite of everything invaluable.

Alina Szapocznikow, Human Landscapes, from 21 October 2017 to 28 January 2018, The Hepworth Wakefield (Wakefield, United Kingdom).

Filipovič Elena and Mytkowska Joanna (dir.), Alina Szapocznikow, Sculpture Undone, 1955-1972, exh. cat., The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 7 October 2012-28 January 2013, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, 2012.

2

Storsve Jonas (dir.), Alina Szapocznikow, du dessin à la sculpture, exh. cat., musée national d’Art moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou, Paris, 27 February-20 May 2013, Paris, Dilecta / Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2013.

3

The second version, bronze cast and presented on a rough stone like an unexpected altar, accentuates even further its relic-like character.

4

Hélène Gheysens, Pierre Restany et les artistes femmes, au miroir de Lea Lublin, research paper master 2, directed by Sophie Duplaix and presented at École du Louvre, Paris, in September 2016.

Hélène Gheysens, "Alina Szapocznikow, Essential, at the Hepworth Wakefield." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/alina-szapocznikow-essential-at-the-hepworth-wakefield/. Accessed 1 July 2025