Marie Laurencin

Marchesseau Daniel, Marie Laurencin (1883-1956). Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, Chino, Musée Marie Laurencin, 1986

→Groult Flora, Marie Laurencin, Paris, Mercure de France, 1987

→Marchesseau Daniel (ed.), Marie Laurencin, exh. cat., Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris (21 February–30 June 2013), Paris, Musée Marmottan-Monet / Hazan, 2013

Marie Laurencin, Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris, 21 February–30 June 2013

French painter.

Born out of wedlock, Marie Laurencin’s Creole mother ensured that she had a middle-class education. She, however, chose to devote herself to art and enrolled in the Ecole de Manufacture de Sèvres (a state-run porcelain factory), where she learned to paint on porcelain. While continuing to value and practice the decorative arts, she also learned fine art painting through private classes at l’Academie Humbert in Paris starting in 1904. There, she met Francis Picabia, and more importantly Georges Braque, who introduced her to Pablo Picasso and members of his circle. A regular at the Bateau-Lavoir, she was romantically involved with the writer Guillaume Apollinaire between 1907 and 1912 (Apollinaire and friends, a country gathering, oil on canvas, Musée national d’Art moderne, Paris, 1909). Although her work is situated on the fringes of Cubism, Laurencin regularly exhibited with the Cubists, including at the Salon des indépendants and with the “Section d’Or” at the Galérie La Boétie in 1912; also in 1912, she participated in the decoration of the maison cubiste by Duchamp-Vilion and André Mare, exhibited at the Salon d’automne. In June 1914, she married the Francophile German painter Otto von Watjen, and soon after had to flee to Spain following the declaration of war. Traveling between Madrid and Barcelona, she collaborated with Picabia at the magazine 391. After traveling through Dusseldorf, she returned to Paris on her own in 1921, after which she enjoyed a period of great success.

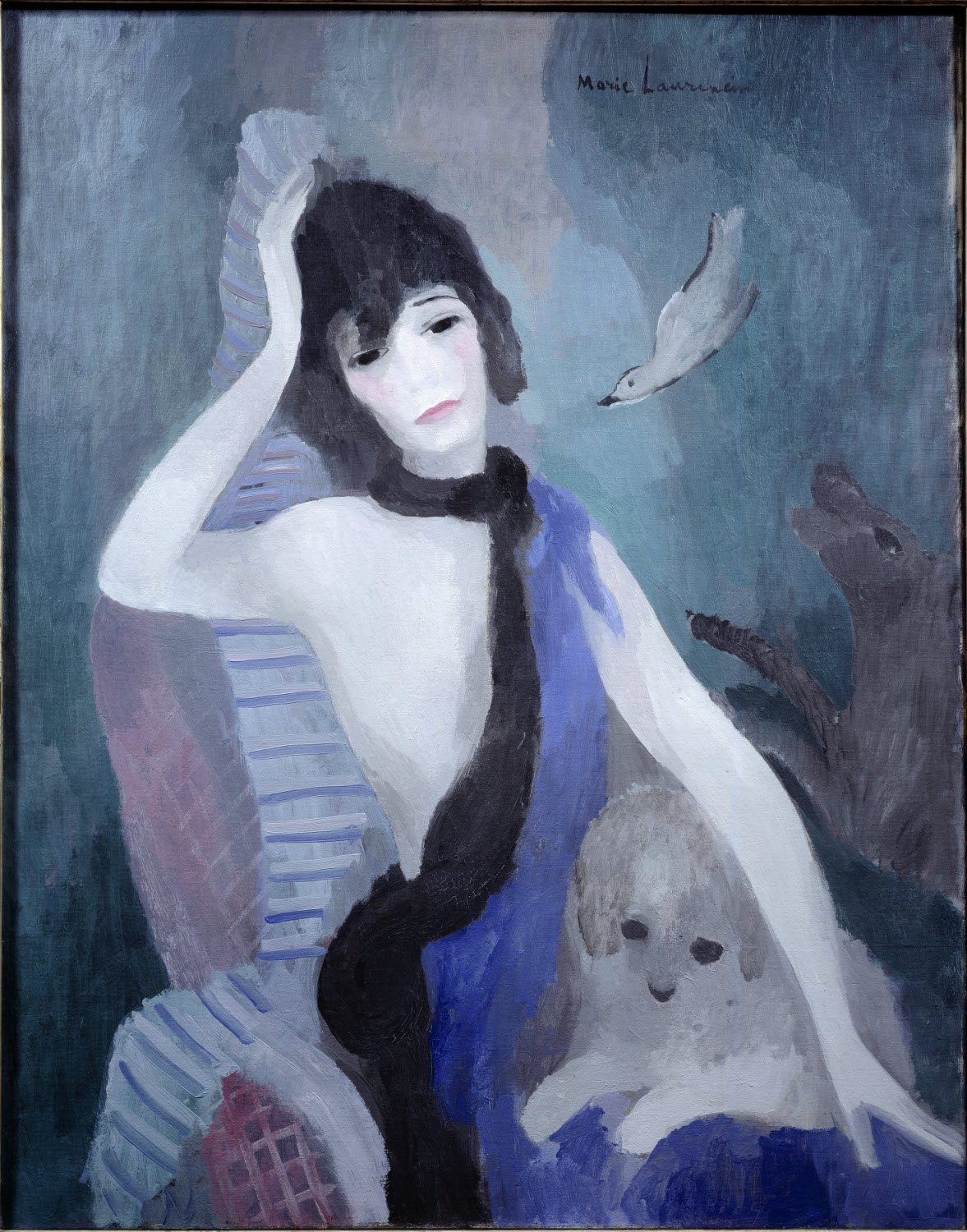

Represented by the dealer Paul Rosenberg in Paris since 1913, and by Alfred Flechtheim in Berlin, she exhibited regularly, sold many pieces, and received numerous commissions. Portrait de la baronne Gourgeaud à la mantille noire (MNAM, Paris, 1923), Portrait de Mlle Chanel (Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris, 1923): many important personalities of the interwar period wanted their portraits painted by Laurencin. Her work is primarily influenced by Matisse’s style and the sincerity of Douanier Rousseau. As for Cubism, to which she would forever be linked, she borrowed the simplification of forms and the abandonment of the model, painting instead flattened figures in a nearly perspective-free space, as in the mise-en-scene of Apollinaire et ses amis. After this work, however, she seemed to withdraw from the group, and her work from the interwar period only serves to strengthen this impression. Her paintings, which mostly represents young adolescents, women, and children, are imprinted with a grace considered entirely feminine by the critics of the time, which the painter did not deny. With pastel tints, and delicate features, she created an idealized figure of femininity similar to her contemporary Jaqueline Marval, with whom she shared her first exhibit at the gallery of Berthe Weill (1865-1951) in 1908. These paintings of women were not, however, a simple representation of an atemporal gilded age; they were particularly representative of the liberated woman of the 1920s. Lesbian overtones were not absent from her work, particularly in her portraits of Nicole Groult (1887-1967), the sister of Paul Poiret, with whom the artist had a romantic affair during her exile in Spain: Femmes à la colombe, Marie Laurencin et Nicole Groult (à la colombe) (Paris, MNAM, 1919). In addition to painting, the artist also produced engravings and works of decorative art. She created, over the course of her career, more than 300 engravings and illustrated many books.

In 1923, she created the sets and costumes for the Russian Diaghilev ballet’s production of Les Biches, illustrated a booklet by her friend Jean Cocteau, and created other works for the stage through the end of the 1920’s. She also taught, starting in 1933, at l’Académie du XVIe in Paris, founded by the engraving master Jean Émile Laboureur. Her production in the 1930’s and 40’s was somewhat repetitive. Starting in the 1990s, her work starting attracting new interest, mostly due to her success in Japan, which saw in her work not only a feminine grace but a distinctly French one. In 1983, a museum dedicated to Marie Laurencin was created in Tateshina.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Marie Laurencin's portrait, 1979

Marie Laurencin's portrait, 1979