Mary Linwood

Heidi Strobel. The Art of Mary Linwood: Embroidery, Installation, and Entrepreneurship in Britain, 1787–1845, London: Bloomsbury, 2024

→Matthew Craske. “Mary Linwood of Leicester’s Pious Address of Violent Times”. The Journal of Religious History, Literature and Culture, vol. 7, June 2021, number 1, pp. 1–34

→Rosika Desnoyers. Pictorial Embroidery in England: A Critical History of Needlepainting and Berlin Work, New York: Bloomsbury, 2019, pp. 20–33

→Mary Linwood, Embroidered Paintings by Mary Linwood (1755–1845). Miss Linwood’s Gallery of Pictures in Worsted: Leicester Square, London: Rider and Weed, printers, Little Britain, 1812

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe 1400–1800, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, October 2023–January 2024; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, March–July 2024

→Miss Linwood’s Exhibition, Saville House, Leicester Square, London, 1809–1845

→Pantheon Assembly Rooms, Oxford Street, London, May 1787

British needleworker.

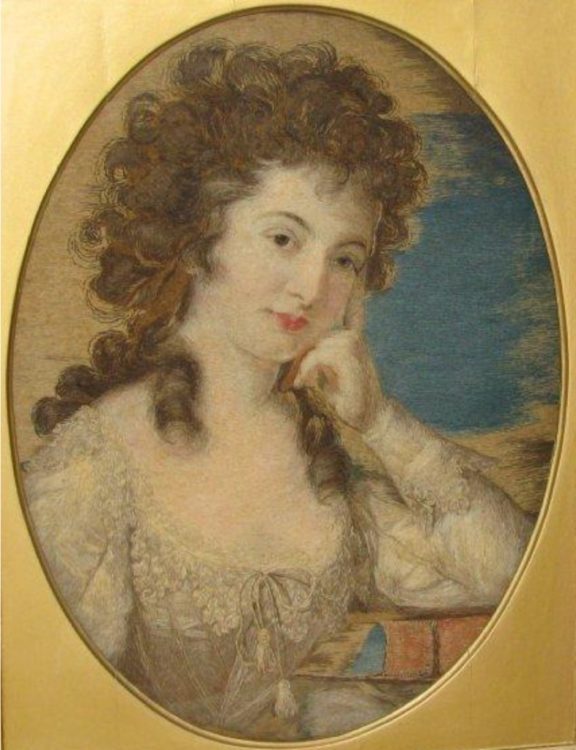

Mary Linwood enjoyed an international reputation for her skilled needlework. As the first woman artist to own her own gallery in London, she made her mark both through her genre-defining textiles and her entrepreneurial spirit, exhibiting but not selling her compositions. In 1809 M. Linwood opened her gallery in Leicester Square, which she operated until her death. The space held over 60 textiles, installed in lushly appointed rooms and engaging, inventive vignettes. Her faithful crewelwork reproductions of artworks by leading painters as well as her original compositions put needlework into conversation with the so-called ‘noble’ art of painting, promoting artistic literacy and foreground British art. M. Linwood’s mastery of her medium was widely recognised by the public who paid to see her exhibition and by patrons such as Queen Charlotte.

M. Linwood’s education in needlework probably began like that of most young girls, through studying embroidery under the direction of her mother, practicing common stitches by making samplers and learning from pattern books. Her work was neither kitsch nor craft, nor did it conform to established academic traditions. She worked primarily in worsted wool, building compositions through stitches that were angled and layered with subtle shifts in colour to imitate brushstrokes or a heavy impasto. In her version of George Stubbs’ (1724–1806) Tigress, now in the collection of the Yale Center for British Art, M. Linwood’s command of colour and texture can be seen in her masterful treatment of the animal’s fur juxtaposed with her ability to transform inherently soft wool into a backdrop of cool stone.

Throughout her life, M. Linwood championed accessibility and education alongside her entrepreneurship. She worked as an educator at the boarding school founded by her mother while maintaining her gallery as a destination where visitors could discover the intersection of skilled artistic labour and the work of leading painters. The roster of works and their installation remained steadfast throughout their decades-long display, with M. Linwood repeatedly refusing to break apart her oeuvre. She replicated, in wool, works by Guido Reni (1575–1642) and Carlo Dolci (1616–1686), although she heavily favoured the British school including Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) and Maria Cosway (1760–1838). Her carefully curated collection of copies, as well as her original works, included many landscapes but also showcased her talents in portraiture, still life and historical scenes.

As an unmarried woman, M. Linwood had both increased freedom to pursue her artistic goals and an added impetus to support herself. In her will, she left one of her most noted works, a Savator Mundi after Dolci, to Queen Victoria, in recognition of the monarch’s enduring support for her career. M. Linwood’s gallery and its success as a draw for tourists and art lovers paved the way for women like wax sculptor Maria Tussaud (1761–1850), whose pop-up exhibitions were contemporary with those of M. Linwood and who followed the needleworker’s lead in opening a permanent London gallery. M. Linwood continued to work well into her 70s, with her gallery of works finally dispersed and sold through Sotheby’s following her death.

A biography produced as part of the programme “Reilluminating the Age of Enlightenment: Women Artists of 18th Century”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2024