Monica Bonvicini

Kraynak Janet (ed.), Monica Bonvicini, London, Phaidon, 2014

→Dorin Lisa (ed.), Monica Bonvicini: Light Me Black, exh. cat., Art Institute of Chicago (20 November 2009–24 January 2010), Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, 2009

→Fricke Harald, Monica Bonvicini – Platz machen, Berlin, Kulturwerk des BBK, 1994

Monica Bonvicini: Anxiety Attack, Modern Art Oxford, Oxford; Tramway, Glasgow, 2003

→BOTH ENDS, Kunstalle Fridericianum, Kassel, 28 August–14 November 2010

→3612,54 m3 vs 0,05 m3, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin, 16 September 2017–26 February 2018

Italian visual artist.

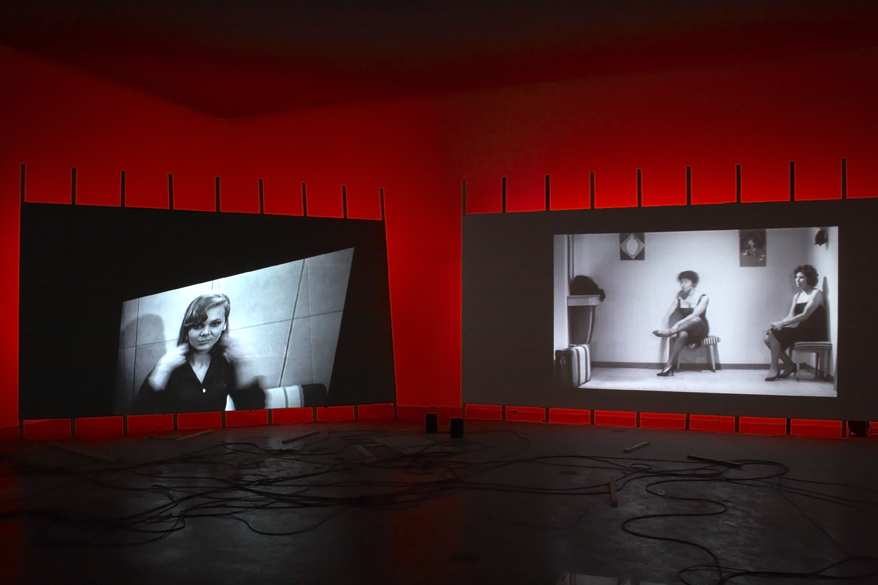

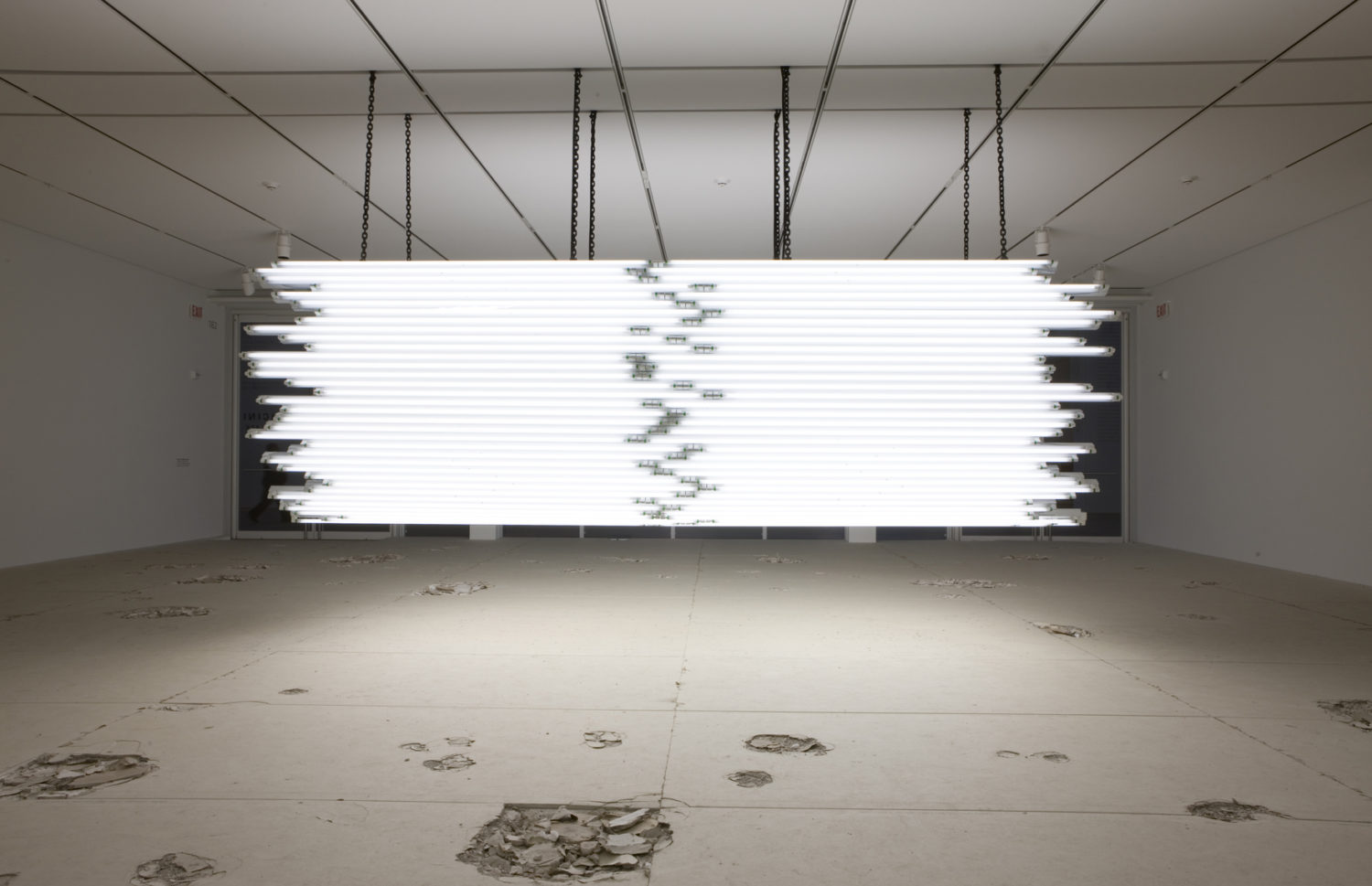

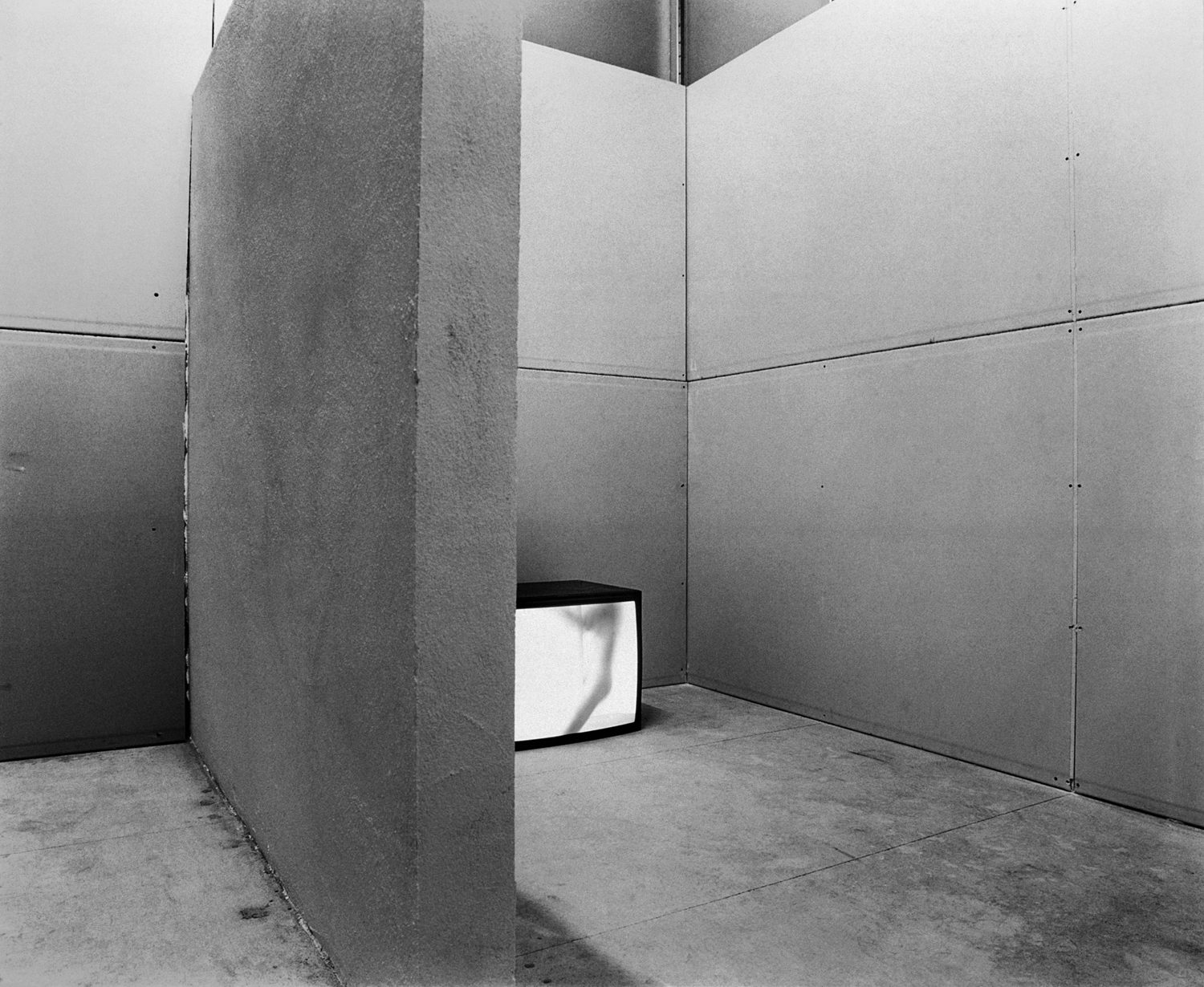

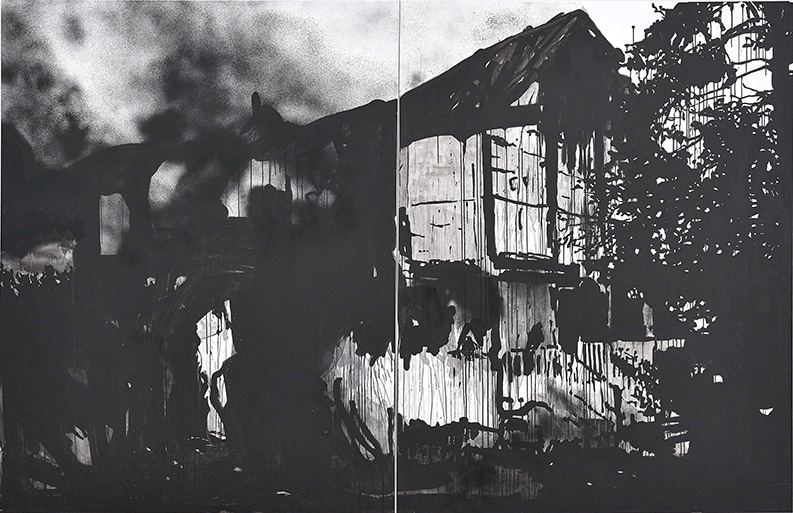

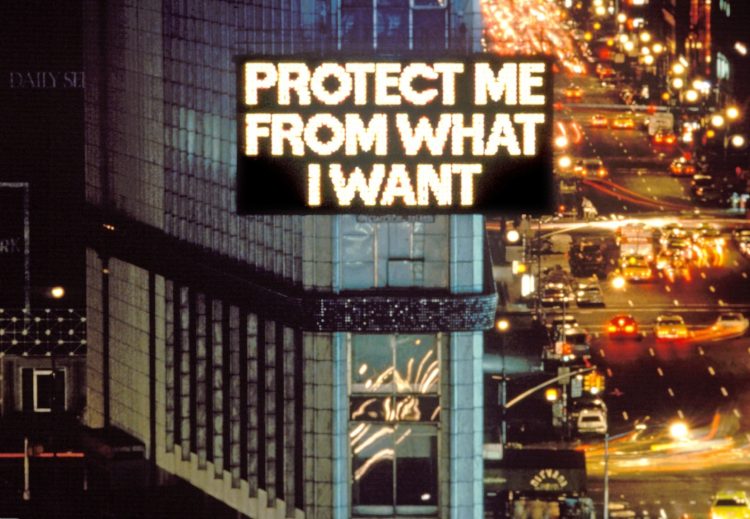

Monica Bonvicini studied in Berlin (1986-1990), then in Los Angeles, at the California Institute of the Arts (1991-1992). Her work was presented in the mid-1990s and soon propelled her onto the international stage, with exhibitions held in many institutions (Kunstmuseum in Basel, Le Magasin in Grenoble, the Kunsthalle in Kassel, Palais de Tokyo in Paris, Museum of Contemporary Art in Vigo, Palazzo Grassi in Venice, and the Secession in Vienna). She obtained the Lion d’Or at the Venice Biennale in 1999 and the Berlin National Gallery Prize in 2005. In 2007, she won a public commission: a floating sculpture, opposite the new Opera House of Oslo (Norway). Her work is “political” and deeply rooted in contemporary society. The artist questions, sometimes violently, the traditional power structures governing male-female relationships and methodically deconstructs social, cultural, and identity-based systems of values. She thus undertakes a critical analysis of architecture, its codes and representations, in terms of sexuality: I Believe in the Skin of Things as in that of Women (1999), a title borrowed from a quote from Le Corbusier, consists of a plasterboard space whose walls bear citations from famous architects, juxtaposed with caricatured and sometimes obscene drawings that ridicule the great masters of modernism. Physical destruction is sometimes added to the moral destruction, as in Hammering Out (an old argument) (1998), a filmed performance showing a woman’s arms striking a wall with the blows of a hammer, or Plastered (1998), a fake floor covering an exhibition space, destined to be destroyed by the flow of visitors. Without being truly participatory, Bonvicini’s creations involve spectators in a particular process, from which they are sometimes rejected, but for which they remain the target. In this way, while the inscriptions in light bulbs and mirrors in Not For You (2006) address visitors, they also leave them out. The body in a space, in a building, within a given environment, constitutes one of the problematics that the artist develops throughout her work.

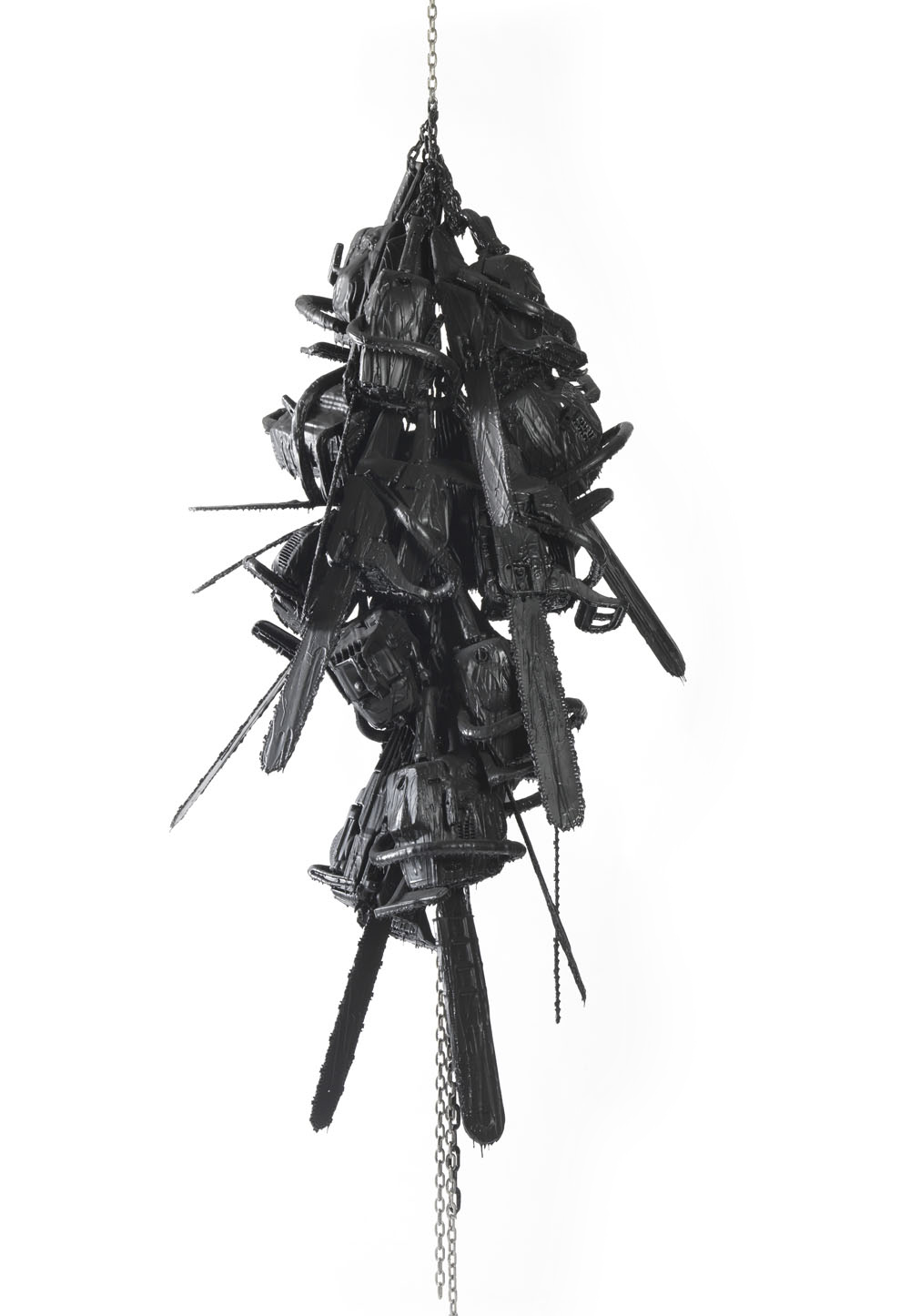

While architecture constitutes a field of questioning of power relations that reveals a male-female power imbalance, from the 2000s, the artist has diversified her research, focusing on other forms of domination, such as the practice of sadomasochism, appropriating its characteristic elements – black leather and steel chains – which she combines with metal grids and shattered glass, subverting all of this in service to powerful and sardonic stagings (Never again, 2005; Identity Protection, 2006). Leather thus becomes an emblematic material in many of her artworks (Black You, 2010; Leather Chainsaw, 2004; Leather Tools, 2009), as do steel chains (Black, 2002; Knotted (big) 2004; Stairway to Hell, 2003; and Scale of Things [to come], 2010). Whether defined by their absence or presence, women play an important role, especially in performances that denounce masculine hegemony (Hausfrau Swinging, 1997; Wallfuckin’, 1995-1996). Through her approach, the artist develops a discourse that falls within the legacy of the feminist movements of the 1970s, such as the Feminist Art Movement, a very active group whose aim was to fight sexism. However, here it is not so much a matter of taking up a position in favour of women as it is of deconstructing the traditional relationships between the sexes within society. In her works, the woman is therefore not considered an object of desire or categorised by a series of clichés. For M. Bonvicini, women are a potentially destructive force, capable of destabilising authoritarian structures and overthrowing masculine domination, sometimes becoming the dominant party themselves.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Monica Bonvicini at Venice Biennale 2011

Monica Bonvicini at Venice Biennale 2011  Monica Bonvicini at Max Hetzler Berlin

Monica Bonvicini at Max Hetzler Berlin