Romaine Brooks

Chadwick, Whitney; Lucchesi, Joe (ed.), Amazons in the Drawing Room: The Art of Romaine Brooks, exh. cat., National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. (29 June–14 September 2000), Chesterfield / Berkeley, Chameleon Books / University of California Press, 2000

→Wermer, Françoise, Romaine Brooks, Paris, Plon, 1989

→Chavanne, Blandine; Gaudichon, Bruno (ed.), Romaine Brooks (1874-1970), exh. cat., Musée Sainte-Croix, Poitiers (27 June–30 September 1987), Poitiers, Musée Sainte-Croix, 1987

Romaine Brooks, Galeries Durand-Ruel, Paris, March 1905

→Romaine Brooks (1874-1970), Musée Sainte-Croix, Poitiers, 27 June–30 September 1987

→Amazons in the Drawing Room: The Art of Romaine Brooks, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., 29 June–14 September 2000

Anglo-American painter.

Born to well-off American parents who separated shortly after her birth, Romaine Brooks was abandoned by her mother, an eccentric woman obsessed by the mental illness of her eldest son. In 1895, she settled in Paris against the wishes of her mother, who nevertheless gave her an allowance. She took singing lessons, but eventually turned to pictorial art. In 1898, she went to Rome to take nude drawing classes at the Scuola Nazionale, where she was the only woman. That summer, she discovered Capri, haven for many English homosexuals after the trial of Oscar Wilde. It was probably at that particular moment that she introduced the notion of “stoned” (people), which, for her, defined the homosexual. She found a studio and lived on the island for almost two years, interrupted by one or two study trips to Paris, at the Colarossi Academy. When her mother died in 1901 she inherited a considerable fortune and was able to paint without money worries. In 1902 she got married on paper to an amateur pianist encountered on Capri, whom she left after a few months, but not before providing him with an annual income. That arrangement, which was widespread among many homosexuals of the day, would permit them to make their respective sexual choices in all independence.

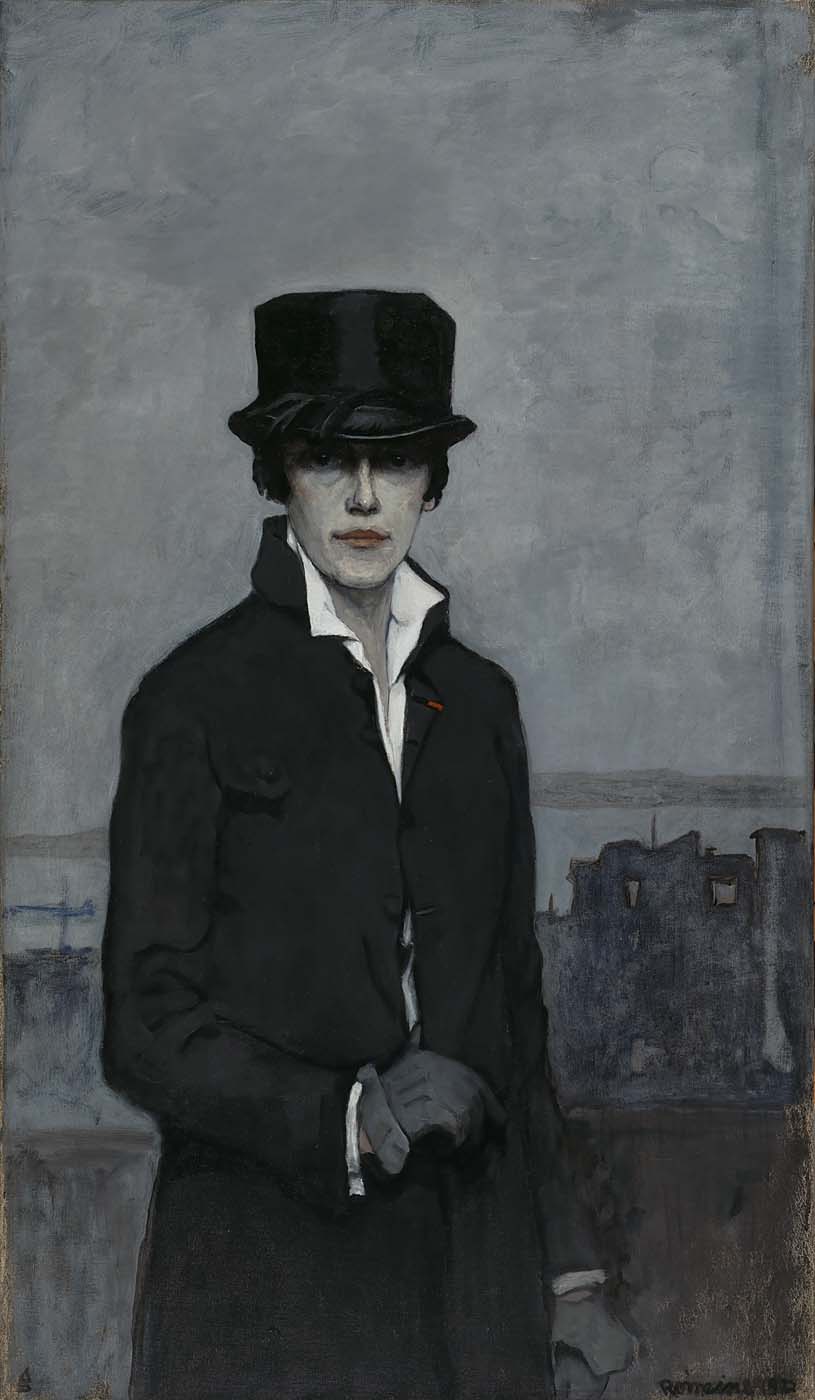

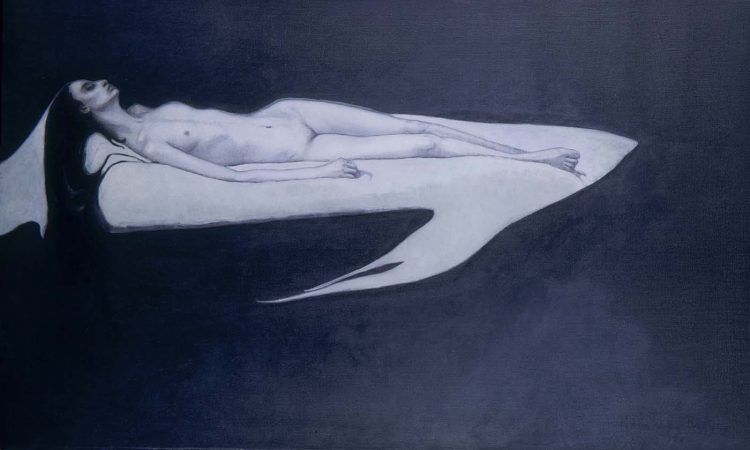

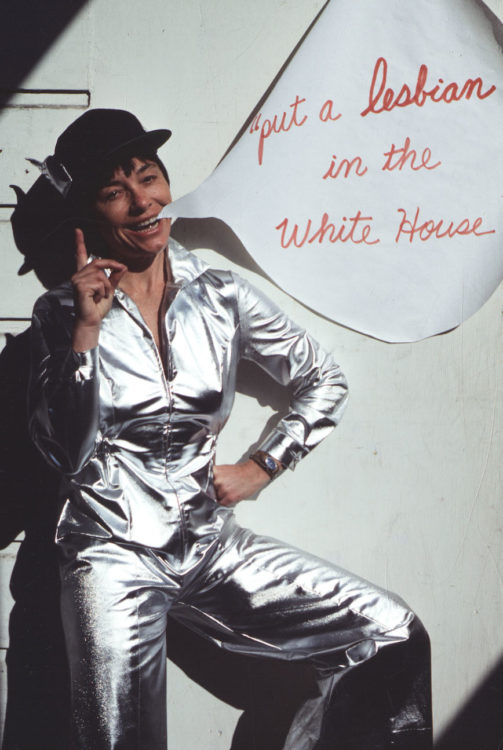

The artist spent a lengthy period in London, where she absorbed the influence of Walter Sickert, Max Beerbohm, and Aubrey Beardsley; her visit to St. Ives (Cornwall) transformed the colours of her palette into grey, ochre and black. In 1905, she settled in Paris, and in 1910 organized her first solo exhibition at the Durand-Ruel Gallery; in it, essentially, she showed portraits of women and one or two nudes. In an article for Le Figaro, Montesquiou nicknamed her a “thief of souls”. That same year saw the beginning of her faithful amorous friendship with Gabriele D’Annunzio, of whom she made several portraits (Le Poète en exil [1910-1912] would be purchased by the Musée du Luxembourg). She also met the dancer Ida Rubenstein, her ideal of androgynous beauty, who was her inspiration for a complex painting about the female nude, a pictorial genre which she tried to renew and eroticize, by avoiding details; she nevertheless remained something of a martyr. In 1915, she got to know Natalie Clifford Barney, with whom she had a liaison, so to speak, until her death. From 1909 on, in her salon on Rue Jacob, the rich American feminist welcomed a shrewd mixture of women—lesbians, journalists, writers, artists, and upper-class ladies, English speakers and otherwise—which defined a new type of modern and independent woman in Left Bank Paris. Her theme would then shift from the martyrology of the “stoned”, to that of the Amazon, which she developed around the portrait of Clifford Barney (Amazone, 1920), using for her models women who regularly attended her salon, and even herself.

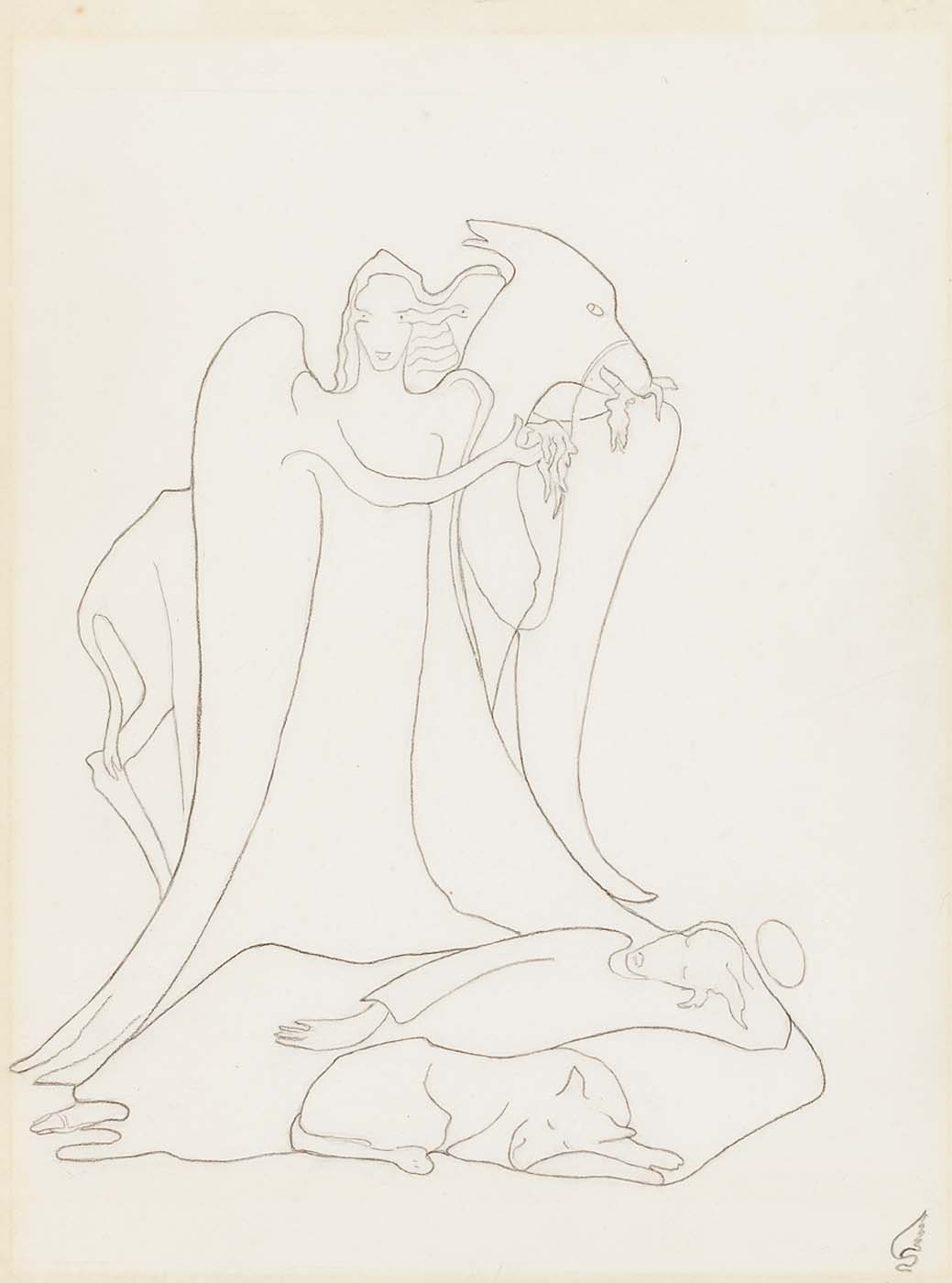

From her earliest days, the artist sought ways of showing a new female portrait, on the sidelines of traditional codes and statuses, and how to make it a symbolic equivalent of the male portrait. She likewise strove, through self-portraits, to express her position as a female artist, without encumbering herself with the tools of the trade: easel, palette. In this way, the portraits of her lesbian friends enabled her to develop the representation of an asserted identity, presented and claimed as such, far removed from the sexual clichés defined by male painters during the 19th and early 20th centuries; they seem like an initial attempt to demand, in painting, a new place for women within a universal framework. From 1925 onward, Brooks showed her works in solo exhibitions in Paris and New York, but she stopped painting in favor of drawing, a medium through which she conjured up her difficult childhood, striving for a maximum of expression with a minimum of means. At the same time, she started to write her memoirs, titled No Pleasant Memories, which would not be published in her lifetime.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Romaine Brooks, elle@centrepompidou (INA)

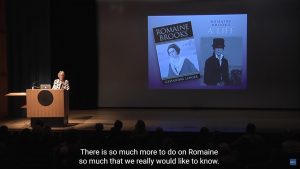

Romaine Brooks, elle@centrepompidou (INA)  Cassandra Langer - Romaine Brooks, 20th-Century Woman - Art Discussion, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Cassandra Langer - Romaine Brooks, 20th-Century Woman - Art Discussion, Smithsonian American Art Museum