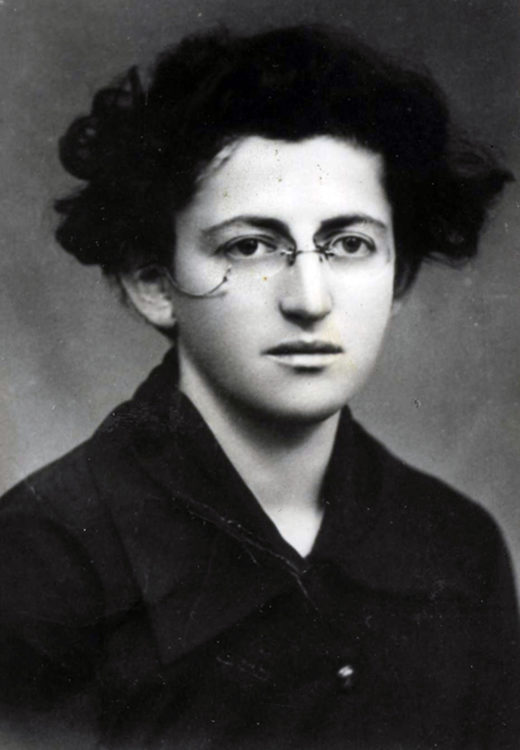

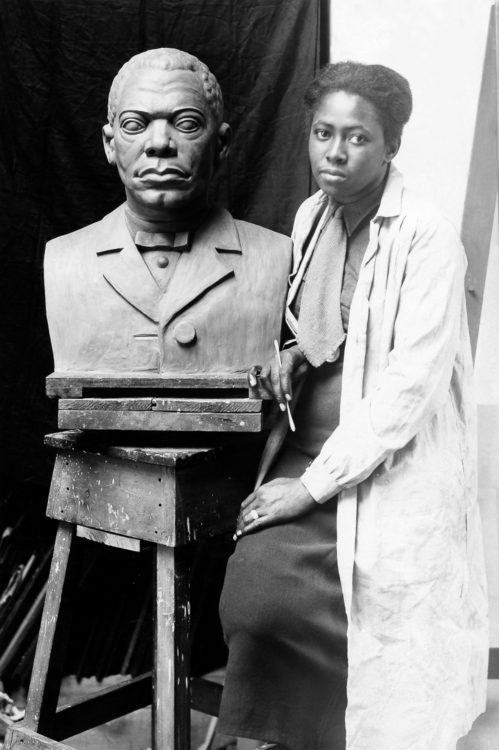

Sarra Lébédéva

Trois sculpteurs soviétiques : A. S. Goloubkina, V. I. Moukhina, S. D. Lebedeva, Paris, Musée Rodin, 1971

Sarra Lebedeva, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, 1 April – 12 June 2020

Russian sculptor.

Sarra Dmitrievna Lébédéva received a private education in Saint Petersburg, where she received artistic training at the School of the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts as well as in the studio of the Mikhail Bernstein in 1910. While studying sculpture between 1912 and 1914, she travelled to France, Germany, Austria and Italy before collaborating with the ceramist Nikolai Dmitriyevich Kuznetsov for the decoration programme of the Yusupov Palace. In 1915 she married the painter Vladimir Lebedev. After the 1917 revolution she became professor at the Svomas (free state art studios) in Petrograd, where she worked closely with, amongst others, Vladimir Mayakovsky with whom she and her husband realised propaganda posters for the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA). She also created monuments honouring revolutionary heroes (Danton, Robespierre, Herzen), taught at the Stieglitz Institute (1919-1920), and experimented with various artistic styles, including ceramics and stage design.

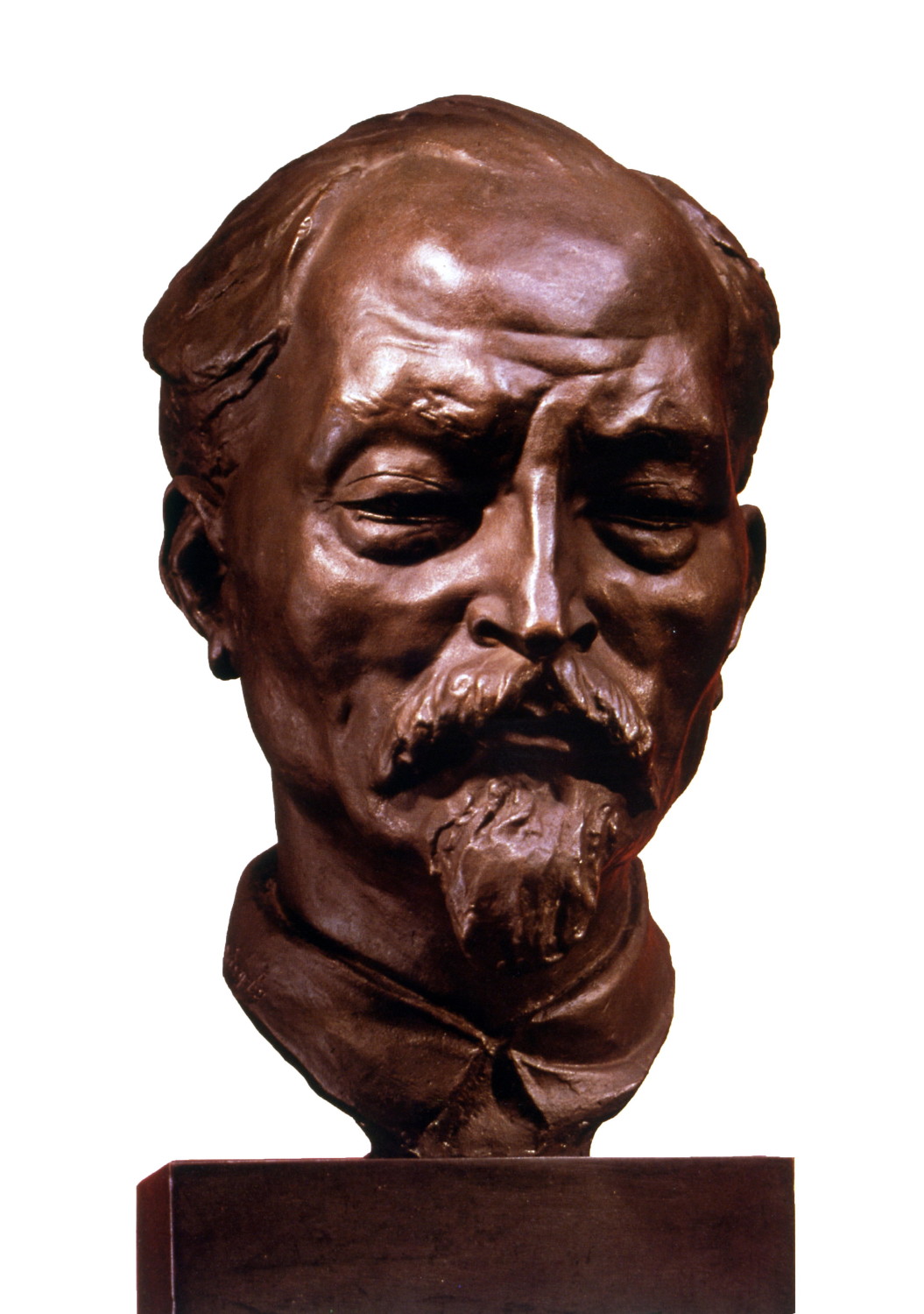

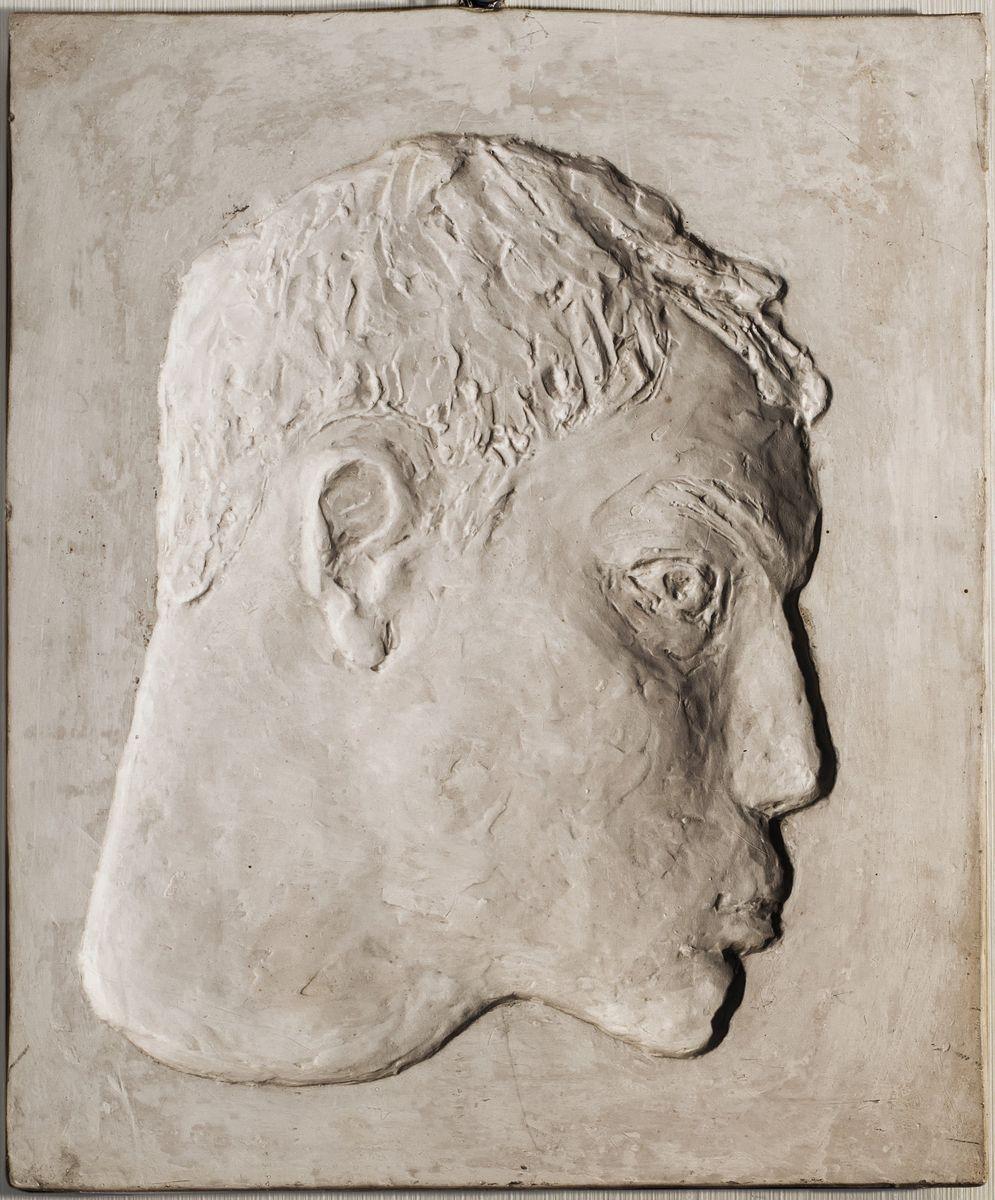

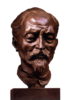

After separating from V. Lebedev she moved to Moscow in 1925 and became a member of the Society of Russian Sculptors. She exhibited regularly in the city and participated in the Venice Biennale in 1928. During the 1930s she created a 2-metre high sculpture in the Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure in Moscow, Fillette et papillon (1936) whose monolithic character, flexibility and dynamism was praised. Children are an important subject in her work (Vania Brouni; Niourka; Fillette aux nattes), as well as female nudes (Liouda). Nevertheless throughout her life her speciality remained portraiture, particularly of her contemporaries, which she created naturally. Like her colleague Vera Mukhina, she went beyond academism with a very vigorous terseness in the treatment of the different facial details. Her portraits often concentrated on the face, which would be placed directly on pedestals rather than emerging from blocks, as seen with followers of Rodin. She preferred bronze, to which she gave various nuances, from matt to shiny. She used this material to represent her artist friends, the heroes of the Second World War and of the revolution, including portraits of the founder of the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky (1925). Close to Vladimir Tatlin in the 1940s and 1950s, she donated the latter’s works and documents to the Russian National Archives. Her reliefs, such as that of Robespierre (1920), show her mastery of the interplay of convex and concave forms.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2020