Shinique Smith

Rapaport Brooke Kamin, “Shinique Smith and the Politics of Fabric”, Sculpture Magazine, June 15, 2021

→Smith Shinique, “Flower of my Heart: Reflection on a Collage”, LALA Magazine Summer, 2020

→Vankin Deborah, “Shinique Smith’s Refuge explores shelter, homelessness and the excess of our stuff”, Los Angeles Times, June 13, 2018

Shinique Smith: Grace Stands Beside, The Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, March 1, 2020 – January 3, 2021

→Shinique Smith: Refuge, California African American Museum (CAAM), Los Angeles, March 14 – September 9, 2018

→Shinique Smith: Bright Matter, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, August 23, 2014 – March 1, 2015

American sculptor and painter.

Shinique Smith began her career as a graffiti artist when still in high school and went on to study painting and drawing at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, graduating in 2003. She then turned to sculpture.

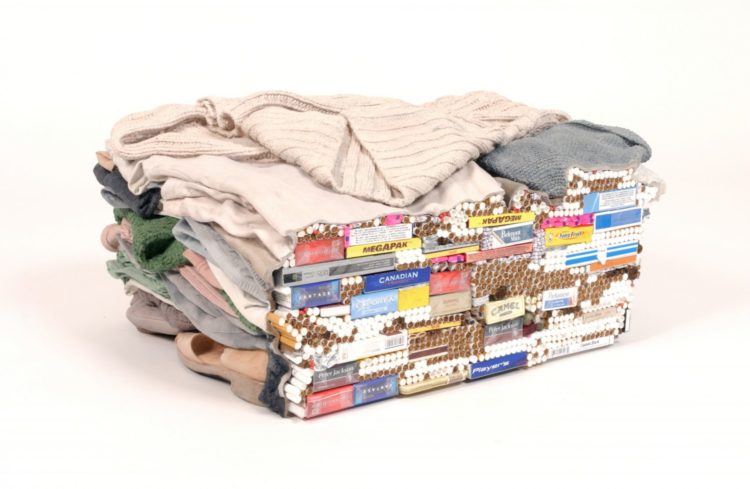

Imbued with a powerful spiritual dimension inspired by Hinduism and Buddhism, S. Smith’s work brings into play a kind of transcendence of everyday objects – she refers to her practice as “frenetic meditation”. Her renowned wrapped sculptures (“bundles”), either suspended or placed directly on the floor, are created from piles of heterogeneous fabrics, usually ragged items of clothing held together by ropes and ribbons. The pleats they create provide a treasure trove for items from everyday life (flowers, stuffed animals, toys, photographs, etc.). These reappropriated objects then become bearers of communal memory: the artist’s own and that of people close to her, as well as unfamiliar figures or communities, not to mention periods of fashion history or popular culture, childhood and adolescence, feelings and the diverse senses of belonging pertaining to each individual. According to the artist, together they create a “cross-section of time, place and meaning”, offering multiple ramifications of their artistic potential.

The series Bale Variants (c. 2005-2019) imitates the compressed bales of second-hand clothes sent to developing countries and posits a view of consumerism and relations stemming from globalisation. The suspended bundles carry what seems to be a more intangible connotation, occasionally triggering a powerful protective or votive message (Talisman for Eternal Delight, 2016): like many of the artist’s works, they possess the poetic nature of a charm evoking love, grace or even forgiveness. In the course of several performances, S. Smith has humanised the form of her sculptures, turning them into equivocal bodies that challenge and reshuffle the traditional categories of gender, race or validity through what Renate Lorenz termed “radical drag” (Untitled [Rodeo Beach Bundle], 2007).

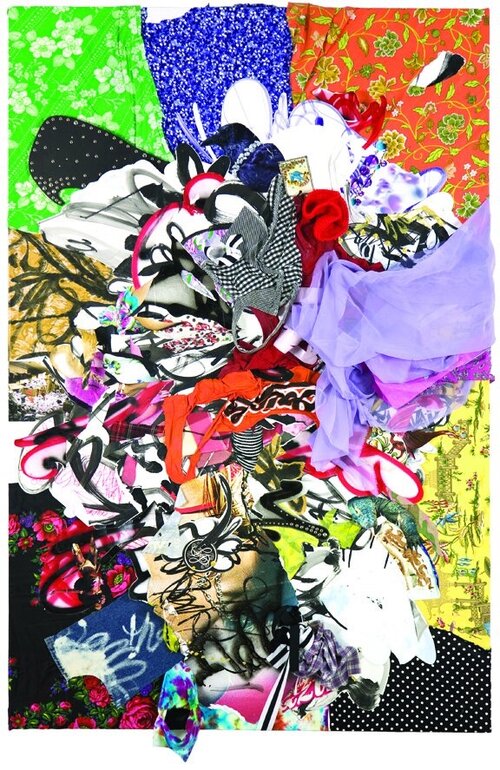

S. Smith has also honed her pictorial practice. In her painted works, she mixes broad, expressive gestures reminiscent of Islamic or Japanese calligraphy with pasted fabrics, to create a series of coloured explosions unfurling their written form from a specific point of origin. Their frequently radiant colour plays a positive psychological role, the dynamic compositions suggesting freedom, abundance or meditation in turn. The artist usually presents her paintings and sculptures together, systematically establishing a dialogue with the space they occupy, either as an installation within a museum (No Dust, No Stain, 2007) or as public art (Only Light, Only Love, 2017). S. Smith thereby creates sanctuaries of a kind, for the most part temporary, which lend a symbolic charge to the space in question and allow us to (re)discover and review our conception of the relationships linking objects, places and human beings.

The works of S. Smith feature in many major American collections, such as those of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The artist has also received a number of prestigious awards, including that of the Anonymous Was A Woman Foundation in 2016.

Shinique Smith: Grace Stands Beside | The Baltimore Museum of Art

Shinique Smith: Grace Stands Beside | The Baltimore Museum of Art