Sylvia Sleigh

Carmine, Giovanni, Hottle, Andrew, Vaillant, Alexis (ed.), Sylvia Sleigh, Geneva, JRP Éditions, 2021.

→McCarthy, David, The Nude in American Painting, 1950-1980, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

→Nochlin, Linda, « Some Women Realists », dans Women, Art and Power and Other Essays, New York, Routledge, 1988, p. 86-108.

Sylvia Sleigh. Un œil viscéral, CAPC / Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux, May16 – Septeember 1, 2013.

→Sylvia Sleigh, “Working at Home“, Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, August 26 – October 2, 2010.

→An Unnerving Romanticism: The Art of Sylvia Sleigh & Lawrence Alloway, Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, March 22 – May 31, 2001.

British-American painter.

Sylvia Sleigh is one of the major feminist artists of the second half of the twentieth century. Her “realist” paintings and drawings offer a re-reading, not to say an aesthetic subversion, of the canons of Western painting, with particular reference to the genres of the portrait and nude.

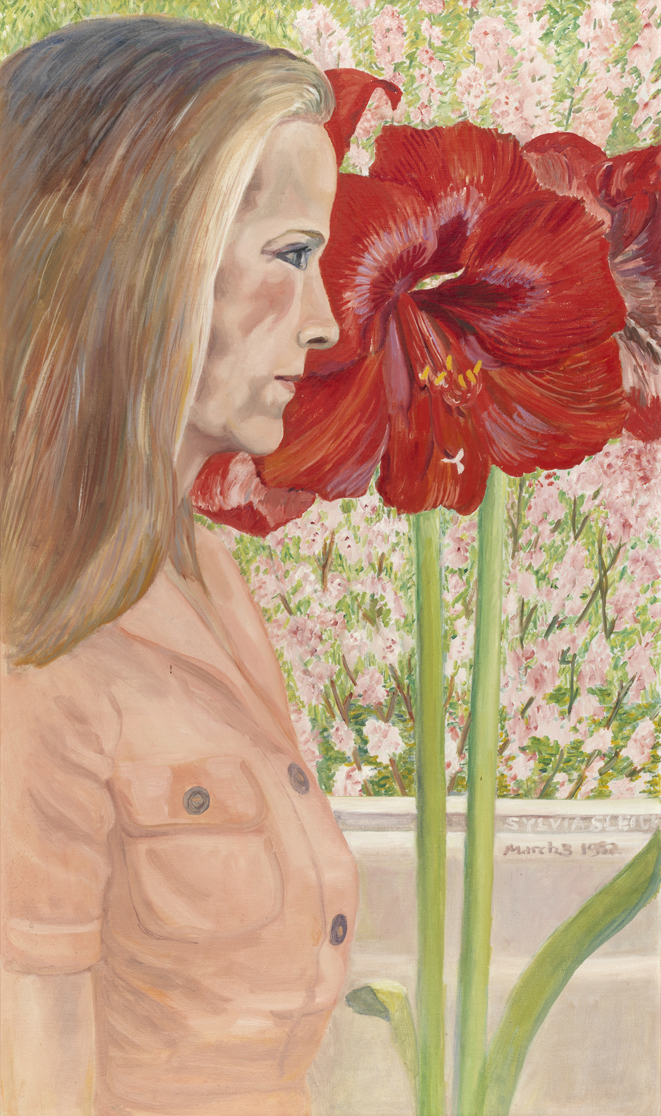

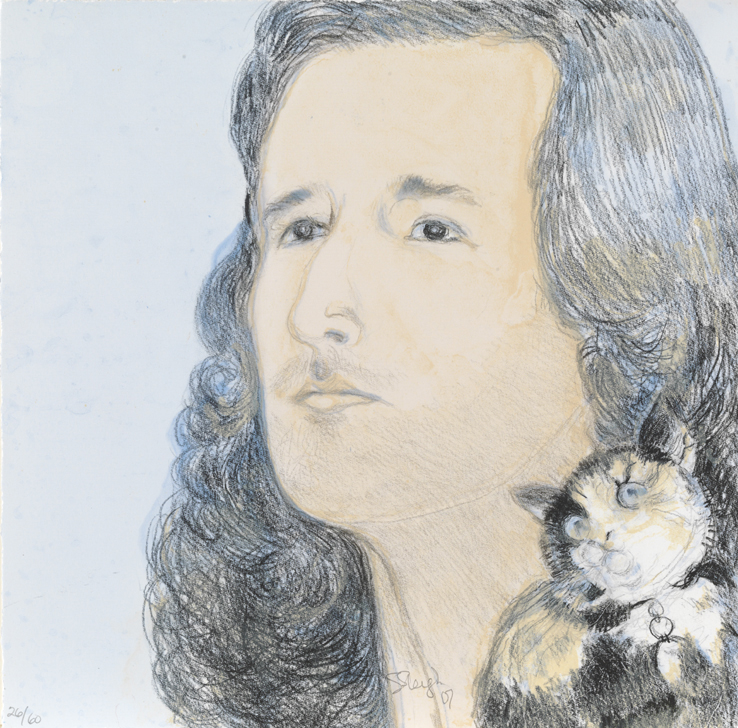

Sleigh was born in Wales and studied at the Brighton School of Art where her teachers were not encouraging. She went on to work in a clothes shop until the beginning of the Second World War. Her first solo exhibition was held in 1953, at the Kensington Art Gallery in London. It featured still lifes, landscapes and portraits in which her signature style was already apparent, characterised by numerous references to art history (and to nineteenth-century painting in particular), a refined and meticulous rendering of the details and decorative motifs adorning or encompassing her figures, and the strikingly frontal nature of the compositions. In 1954 she married Lawrence Alloway (depicted in her canvas The Bride, 1949), an art critic specialising in pop art; in 1961 the couple moved to New York, where S. Sleigh remained for the rest of her life.

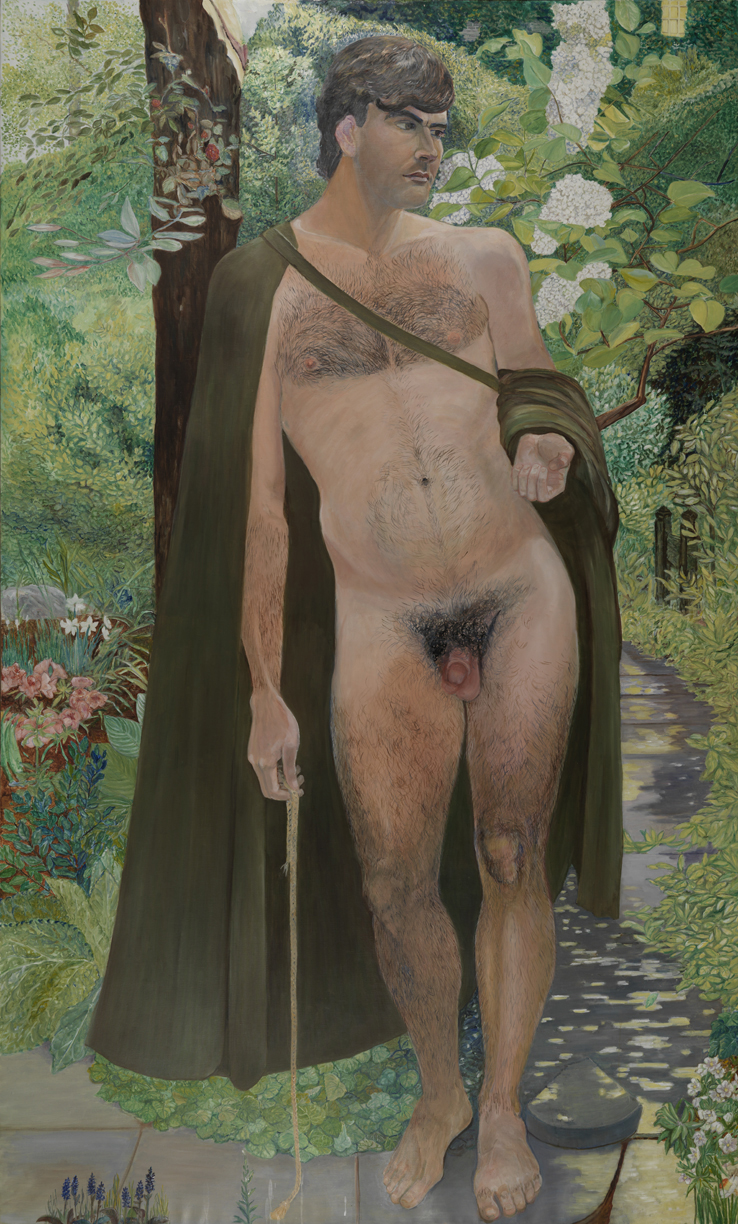

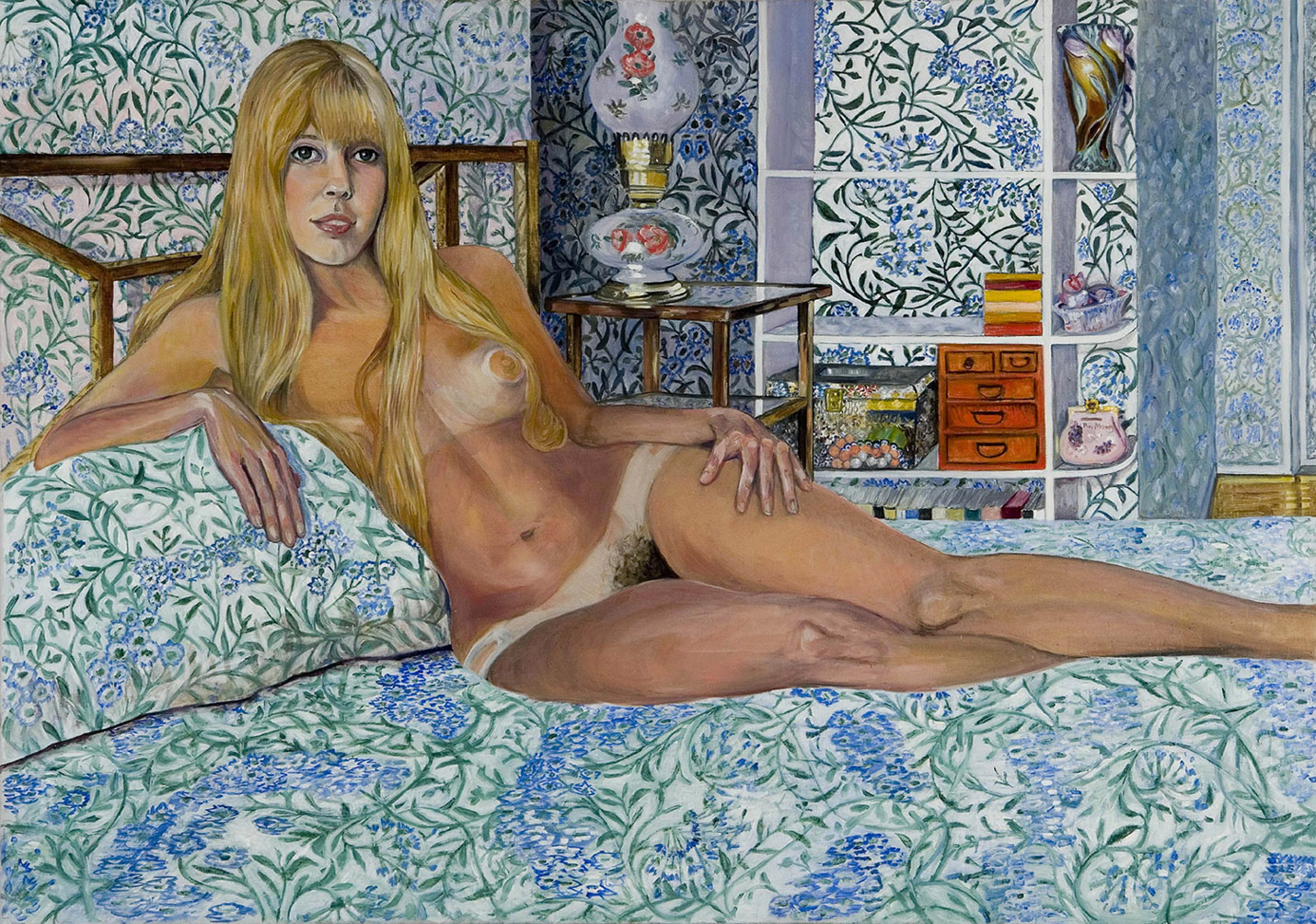

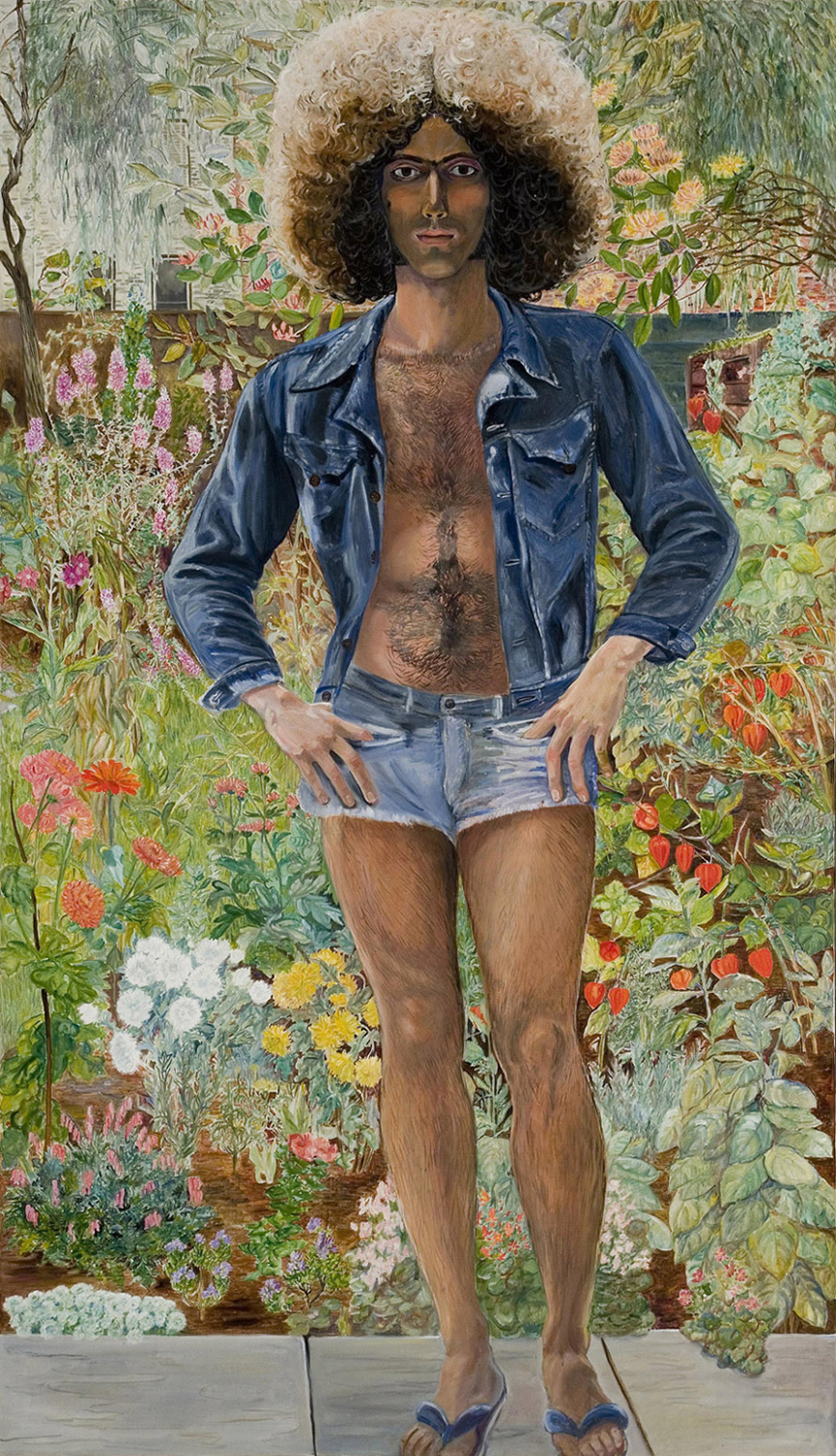

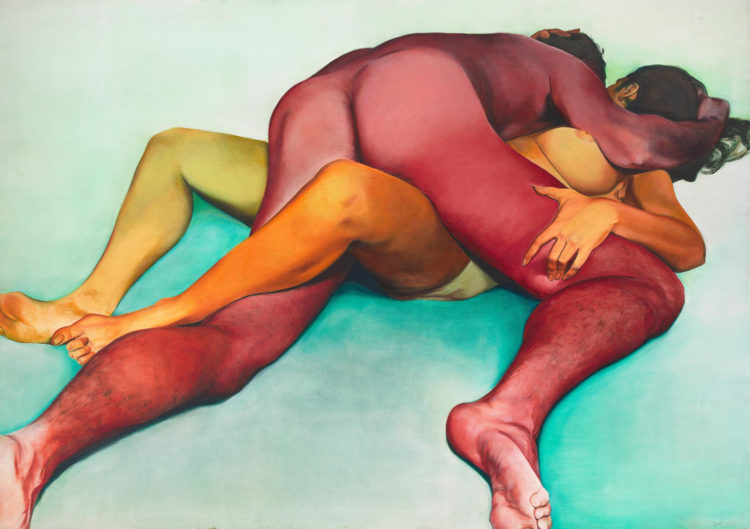

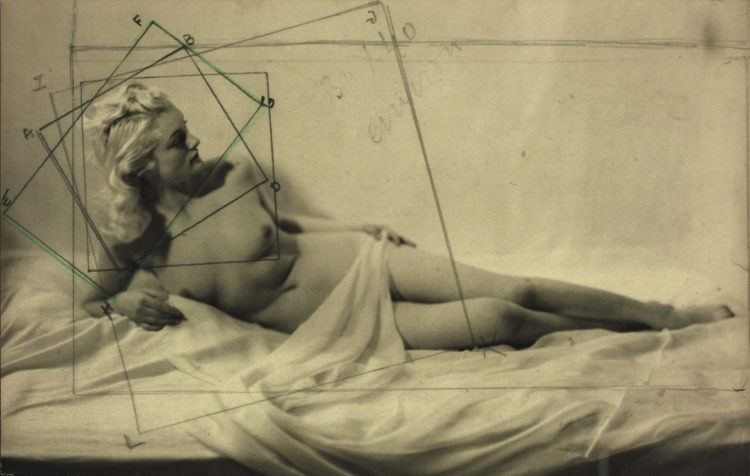

From the late 1960s the artist painted many male and female nudes, which she viewed as portraits in their own right, capable of standing up to the sexual objectification perpetrated by the “male gaze”. Borrowing her compositions and poses from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) (The Turkish Bath, 1976) or from Giorgione (1478-1510) (Concert champêtre, 1976), she melds them into a contemporary setting, lending them the traits of close male and female friends and relatives. Her erotic gaze sublimates rather than minimises the individualised nude bodies with their precisely depicted anatomy and body hair. Rather than overturning the relationship between painter, model and viewer, however, S. Sleigh’s art highlights the equilibrium between them, through positive eroticisation. This applies to her panel entitled Lilith, which she contributed to the collective installation The Sister Chapel (1978), conceived by Ilise Greenstein, in which male and female bodies become indistinguishable.

In the 1970s S. Sleigh began an active campaign to acknowledge women artists and bring about a feminist shift within the American art world. She painted a large number of portraits, established her own personal collection, frequently featuring the works in exhibitions, and supported galleries and artist-run venues such as the A.I.R. Gallery, the first feminist cooperative gallery in the United States, and the SOHO20 Gallery, for which she produced group portraits.

Although it was mainly her male nudes that attracted critical attention for their political impact, S. Sleigh’s oeuvre is to be perceived across a broader spectrum, as a form of celebration – of a community, a political battle and a certain beauty related to the human body but also to nature, rooted in Western art history and transformed by a personal and feminist viewpoint. It is this artistic vision that bursts through the colossal work inspired by Charles Baudelaire and entitled Invitation to a Voyage: The Hudson River at Fishkill (1979-1999), which unites in a bucolic setting – evoking a pastoral fête galante – the artist, her husband L. Alloway and several close friends.

During her lifetime S. Sleigh’s work was shown extensively in American art galleries and at the Hudson River Museum. Major museums such as the Tate in London and the Whitney Museum in New York have acquired her works. On her death, the artist left her collection of approximately one hundred works to the Rowan University Art Gallery in New Jersey. She posthumously received the Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Aard.