Xiao Lu

Skew, 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong, September 12 – October 5, 2019

→Xiao Lu Impossible Dialogue, 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, Sydney, January 19 – March 24, 2019

→Xiao Lu, Skovde Art Museum, Skovde, Sweden, 2017

Chinese performance artist.

Xiao Lu (肖鲁) lives and works between China and Sydney, Australia. She is regarded as one of the most influential artistic figures of the radical and experimental group, ’85 New Wave, and one of the few women to be associated with the movement. She attended the Subsidiary School of the Central Academy of Fine Art, Beijing in 1979, before going on to study oil painting at Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, Hangzhou. After graduating in 1988 she worked at the Shanghai Oil Painting and Sculpture Institute.

Xiao Lu is widely known for her groundbreaking performative action that accompanied her installation, Duihua [Dialogue], which took place during the opening of the first experimental art exhibition, China/Avant-Garde, at the Beijing National Gallery in 1989.

Organised by the influential Chinese curators, Li Xianting, Peng De and Gao Minglu, this show consisted of some three hundred artworks made between 1985 and 1987. However, the government shut down exhibition twice during the two weeks it was open. The first time was after Xiao fired two gunshots at point blank range at the two disused telephone kiosks that made up part of her installation. The ensuing blast and shattering of glass immediately attracted the authorities’ attention, which led to her arrest. She spent two days in custody and charged with public disorder.

Xiao has previously spoken about “accidental elements” being an integral aspect of her performances. Duihua was in fact her graduation piece, created five years earlier and a major departure from her chosen practice, oil painting.

Not long after the events surrounding the shooting in the gallery, and the ensuing fame, in 1989 Xiao withdrew from the art scene and moved to Sydney, returning to Hangzhou in 1997, before moving on to settle in Beijing in 2003 where she resides part of her time.

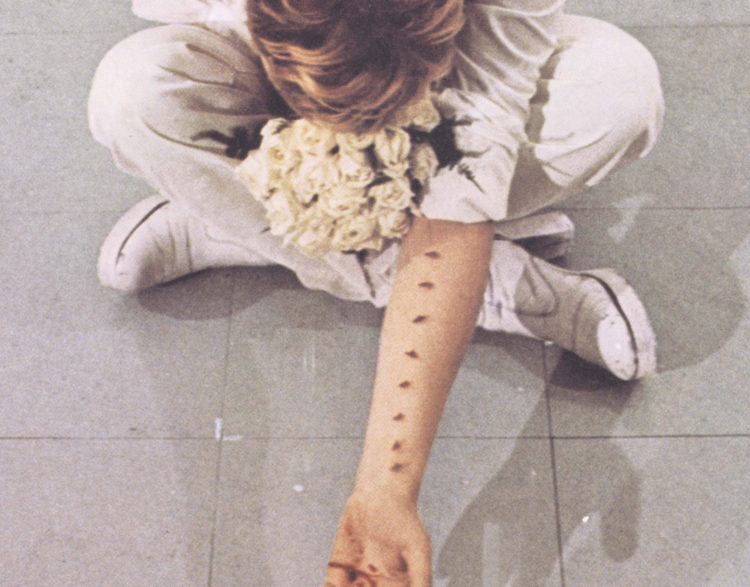

Xiao has a reputation for using her body as her medium and orbiting her performances around personal experiences, and power struggles in particular the complex relationships between men and women. These dynamics are often reflected in numerous dramatic, powerful and unsettling works, including her video installation, Sperm (2006), which relates to an unsuccessful IVF attempt.

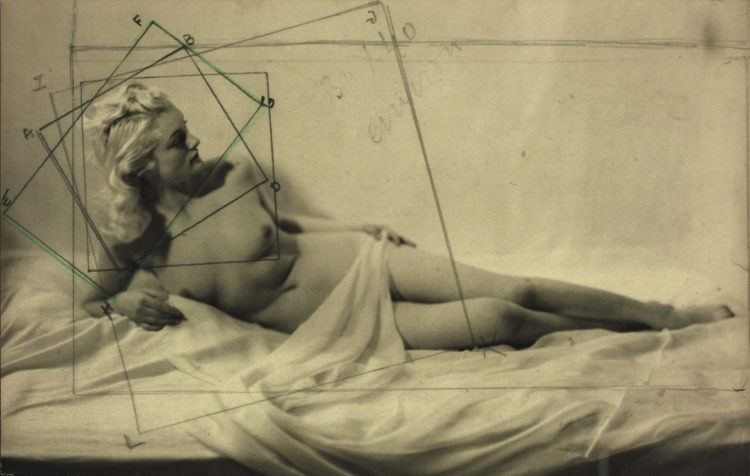

In 2003, Xiao produced 15 Gunshots, From 1989 to 2003, another emboldened body of work that she has described as an artistic and personal turning point, and one which reflects on her first performance piece, plus the collective research of the subsequent fourteen years of artistic practice.

For her performance Toxins at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, part of a Chinese collateral exhibition titled Grand Canal, curated by Xiao Ge, Xiao had a large bucket of mud extracted from Beijing’s own Grand Canal shipped to Italy, with the aim of giving her naked body a Daoist tuina massage, in order to metaphorically expel its toxins. Planned to take place inside a nearby church she was met with resistance by the venue and told the activity could only take place outdoors; mysteriously the bucket and its contents disappeared the day before the intended event. Nonetheless, Xiao decided to enact her performance, disrobing inside the church before heading into the canal for a swim, while framed sheets of papers daubed with essential oils; personal bodily toxins and their chemical analysis were displayed in the venue.

Xiao Lu Impossible Dialogue, a seminal exhibition held three decades after her initial performance, was presented as part of the Sydney Festival in early 2019 at Sydney’s 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, curated by Claire Roberts and Xu Hong. The accompanying international workshop brought together artists, critics and art historians from China, Indonesia and Singapore to debate the question of gender in art.

Such a spirit of resistance continues to be the major force in many of Xiao Lu’s works. She remains one of the very few women whose work has been lauded to herald the beginning of contemporary art in China during the late 1980s. As she has said: “Even if you oppress me and apply a lot of pressure, I will still resist you.”

Interview with Xiao Lu, 2020 | ArtAsiaPacific

Interview with Xiao Lu, 2020 | ArtAsiaPacific  Xiao Lu in 5 minutes, 2017 | White Rabbit Collection

Xiao Lu in 5 minutes, 2017 | White Rabbit Collection