Interviews

Doris Salcedo, Untitled (Homenaje Jaime Garzón), Bogota, 1999, Courtesy White Cube, © Doris Salcedo, © Photo: Doris Salcedo

Following the assassination of political comedian Jaime Garzón on August 13, 1999, Doris Salcedo made several public interventions in the area of the assassination.

This interview was conducted by Carolina Ariza on 21 January 2017 at Doris Salcedo’s studio in Bogota, Colombia. It was made possible thanks to Felipe Arturo, an artist and assistant to D. Salcedo some years ago. A longer version of the interview is included in C. Ariza’s PhD thesis “Une mémoire à l’œuvre. Résurgences artistiques de la ‘petite histoire’ en Colombie” [Memory at work: Artistic resurgences of “little histories” in Colombia].

Carolina Ariza: There is a genuine awareness of history in your work. How did you convert Plaza de Bolívar, the main square of the Colombian capital, into a stage for collective acts of memory?

Doris Salcedo, Act of Mourning, Plaza de Bolivar, Bogota, 2007, 25,000 candles approximately, Courtesy White Cube, © Doris Salcedo, © Photos: Sergio Clavijo & Juan Fernando Castro

Doris Salcedo fills the Plaza de Bolívar with 25,000 candles in response to the assassination of deputies who were kidnapped in 2002 in the Valle del Cauca.

Doris Salcedo, Act of Mourning, Plaza de Bolivar, Bogota, 2007, 25,000 candles approximately, Courtesy White Cube, © Doris Salcedo, © Photos: Sergio Clavijo & Juan Fernando Castro

Doris Salcedo fills the Plaza de Bolívar with 25,000 candles in response to the assassination of deputies who were kidnapped in 2002 in the Valle del Cauca.

Doris Salcedo: I’m not the one who did it. The square has always been a political space shaped by social activism. Any social movement requires some sort of infrastructure in order for people to be able to achieve it. In Bogota Plaza de Bolívar was already an established infrastructure, which various social movements throughout history had chosen as a political rallying point. Its very configuration calls for it – it being an empty space that seems to await occupation. Every year on May 1, it is taken over by crowds. It is a place where the population can voice all of its grievances, all of its issues with the state – the families of missing persons, workers and so on. All I do is come to a plaza that is already loaded with political facets, and I come there as an artist who has just created a work of art. There is nothing improvised about it. I am able to act quickly because I think about it every day, and I act whenever possible, when the time is right. I have called these happenings “mourning actions”. I believe that one of the artist’s duties is to make this kind of tool available to a society which would benefit from mourning daily but of course cannot afford to. Violence is an everyday occurrence in Colombia, and we have reason to mourn the murder of a human rights activist every single day. Unfortunately Colombian society stopped reacting at some point; it wasn’t able to mourn and just decided to stop keeping up. What matters is that we should carry out these acts of mourning. My process is to interfere, to insert myself into the public space obliquely rather than straightforwardly, so that others may in turn reclaim the space for themselves.

CA: Have artists in Colombia ever considered the issue of writing history as a collective?

DS: I think that the concepts of collectiveness and interaction must be tackled from a literal point of view. They have always existed and, in the art world, curiously enough, on the one hand an artist is alone in creating a piece and addressing a topic, but on the other hand it is no coincidence if, when the piece is completed, historians are also happen to be interested in the same topics. All of this comes about without the artists officially claiming to be part of a collective.

CA: Do you think that my generation, the one born in the 1980s, was in a sense programmed to forget?

DS: Of course the system needs forgetfulness in order to function; it would come to a standstill if people were to remember everything. I don’t think it only applies to your generation; I think it concerns all of us. The system tries to conceal things, but information makes its way to us nonetheless.

CA: Did your status as an artist open up possibilities for fieldwork?

DS: I’m not even sure what an artist’s status means. I think division and polarisation have a lot to do with the fact that some people don’t do anything. The system works because people interiorise it. I won’t go so far as to say that going out there is safe, but in contemporary life nothing is completely free of danger. In time of course, one builds support networks that enable one to access these spaces. These networks include women-led non-governmental organisations (NGOs), the judicial system, the attorney general’s office, non-profit organisations (which have helped me a lot), the finance minister and embassies. However, if more people took over these spaces, they would stop belonging to no one.

Doris Salcedo, Sumando Ausencias, Plaza Bolivar, Bogota, 11 October 2016, Courtesy Doris Salcedo, © Doris Salcedo, © Photo: Oscar Monsalve

Doris Salcedo has seven kilometers of white cloth sewn on which the names of the victims are written in ash. She mades this action following the negative response to the referendum on the peace agreement established between the state and the FARC guerrillas.

CA: Do you have any historians working with you in the field?

DS: There have been several historians, including my friend Fernán González,1 a Jesuit priest who works for the Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP, Centre for research and popular education). They all have a novel way of understanding Colombia’s problem – not to sound like a stupid nationalist – but, because this country is a shameful disaster and because it is so violent, a resistance has formed over the years. In Colombia the peace process failed after the “no” won in the referendum. I can go to Plaza de Bolívar to create a piece and have 10,000 people helping, but I’ll also have 300,000 others booing me. When Sumando Ausencias [Counting the missing, 2016]2 was created, the memory remained and we, as survivors, not only freed ourselves but also enabled those who were excluded to exist. In Colombia it wasn’t enough to simply displace the victims, to assassinate them – there was also a will to erase them. With this piece we were able to bring those who had been excluded back to the centre of the country’s politics, symbolised by the Plaza de Bolívar. It was a demonstration of the dead, a demonstration of the missing. Despite the criticism, it exists now and was seen by many.

CA: In Colombia all this violence has clearly become a part of society. There have consistently been many responses to it, and despite fear and intimidation, artists have always denounced human rights violations.

DS: Precisely, and what is happening in Colombia is so frightful that we have no issues with criticising our country because we are not proud of it. It isn’t easy for a society, but for artists, as Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari said so eloquently in their book Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature,3 the scarcity of masters is beneficial, in that they can choose to draw from whatever they please. The same can be said about the concept of “nation”: if you have no idea of what a nation is and if you know that your government will neither defend you nor provide for you, then you end up doing things your own way. In many ways the same principle is also applicable to art: as artists, we take over the public space as a reaction to what is happening in the public sphere.

CA: I would like to discuss the work you created about the Bogota courthouse, 6 y 7 de Noviembre [November 6 and 7, 2002], which clarified a lot about what took place during the massacre: how did you put together all that archival material and where is it now?

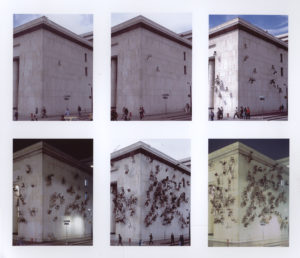

Doris Salcedo, Noviembre 6 y 7, Bogota, 2002, Courtesy White Cube, © Doris Salcedo, © Photo: Sergio Clavijo

Doris Salcedo, Noviembre 6 y 7, Bogota, 2002, Courtesy White Cube, © Doris Salcedo, © Photo: Sergio Clavijo

DS: It happened little by little. The first thing was that I witnessed the events in person, so I had a clear understanding of what had occurred. I was always aware of what was happening. The second thing is that, for many years, I had attempted to get into the courthouse but was never authorised to do so. Then the building was torn down. In addition to this, I was secretly in contact with the morgue. I was able to access autopsies and photographs – all of the photographs and autopsies – most of which weren’t very thorough, as they are more likely to be nowadays. So I had all this material at my disposal and two people helping me gather all the data published in the press. I donated part of these archives to the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, where a forensic anthropology master’s department has been created, but the university being what it is, no one knows where they are now. Later on, in 1995, Beatriz González, F. González and I submitted an exhibition project to the Museo Nacional de Colombia. At that time, the courthouse building had been razed to the ground but its basement still remained. We managed to access it in order to get some footage. What we found was astounding. All the remains of the fire were still piled up there: furniture, desks, typewriters, crucifixes, stacks of books. Everything had melted. The gigantic cabinets in which the volumes of the old Constitution were kept had burned to the ground. The amount of material was incredible. So I put together a project for a permanent exhibition room at the Museo Nacional de Colombia.

CA: Was the idea to use the material as an archive?

DS: The idea was to use the objects that we had found and filmed in the basement. Based on the same argument that is used against me today, which is that I wanted to become famous by exploiting the victims’ pain, the Ministry’s officer started throwing out the contents of the courthouse’s basement. We managed to secretly salvage a typewriter, a chair and a few objects that we exhibited at the Museo Nacional de Colombia, after which someone from the cultural department at the local city council supported our project to have them become part of the museum’s permanent collection. They now belong to the Museo Nacional de Colombia’s collection as anonymous pieces.

CA: Are they to be considered artwork or historical archive?

DS: They are not art – they are objects. The typewriter and chair now belong to the Museo Nacional and they are the only items we were able to salvage. It was the first time I was faced with the impossibility of using objects that carried memory, which is why I created the piece Noviembre 6 y 7. So I decided to simply buy some chairs and I planned the courthouse installation. I asked the Supreme Court, the Constitutional Council and the Ministry of Justice for permission but nobody replied. Thanks to a contact of mine, I was able to covertly enter the building and to work on the roof. We kept at it for two months, at night and on Sundays, and on the eve of the scheduled day, on the 5 November at five or six in the afternoon, I finally received notice that the Supreme Court had green-lit the project.

Doris Salcedo, Noviembre 6 y 7, Bogota, 2002, Courtesy White Cube, © Doris Salcedo, © Photo: Sergio Clavijo

CA: About the chairs: you asked your assistants to find a very specific object that matched a particular period and aesthetic. Could you elaborate on this?

DS: Firstly the chairs I chose had a connection to the type of furniture that I had found abandoned and burnt in the courthouse basement. Furthermore I was interested in working with a specific object. There is this type of chair that for instance cannot be found in France because it is a more basic, more simply crafted piece of furniture that is typical of Colombian interiors. It can be found in houses and in schools alike; it belongs in an intermediate space. It is neither strictly institutional nor exclusively designed for home use – it exists halfway between these two points. That was how I made that choice, all the more so as the chair belongs to interiors, to the intimate lives of people. The function of a chair is to enable a person to sit down; if its function is altered to the point of it becoming a flat surface, a facade, then you know something serious has happened.

CA: Did any of the victims reach out to you after the installation and commemoration? What was the outcome of the event?

DS: This was in 2002, and at the time there were no articles in the press, no inquiry commission looking into a subject that was virtually non-existent. It was all very strange, in that the only people I could discuss it with were my historian friends. It felt as if I was the only one still thinking about the event, that I was perhaps crazy. But when I started working on the piece, I spent a little over fifty hours in the street downtown, and it astounded me to hear people remembering the exact moment and describing it in great detail. I was wrong to think that the memory was lost; it was, in fact, dormant. All the violence they had faced from 1985 to 2002 had devastated them. Memory had become suppressed and we needed an act of recollection, an intention to remember for it to resurface because we are not very good at remembering. The families of the missing and others told me that it had been the only funeral act they were ever granted. It was staggering.

CA: Do you think that today, with the signing of the peace deal in Havana on 26 September 2016 in the context of the peace process between the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), there will finally be an opportunity to rebuild this lost memory?

DS: I think that the scope of the tragedy in Colombia is colossal. It will take us many years and it won’t be easy. I think that historians, the Comisión de Memoria Histórica (Committee for Historical Memory), as well as artists are starting to work on it. The peace process will make it easier for some fragments of memory to resurface: those of the paramilitary, of the various FARC guerrillas, and of the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN, National Liberation Army). We covered part of the paramilitary chapter because they confessed – not because they were good people but because it was convenient. Deals were made and it was worth it because we got information out of them. We already know a lot but there is still a long way to go. There is a great deal of archival material but we still need to study it. In my opinion the peace process doesn’t bring complete reconciliation but brief snippets of peace. The same can be said about memory: all we have are short snippets of memory. As they accumulate, these fragments will come together little by little to form something that will bring us closer to grief. I really do hope this happens!

Doris Salcedo, Sumando Ausencias, Plaza Bolivar, Bogota, 11 October 2016, Courtesy Doris Salcedo, © Doris Salcedo, © Photo: Oscar Monsalve

Doris Salcedo has seven kilometers of white cloth sewn on which the names of the victims are written in ash. She mades this action following the negative response to the referendum on the peace agreement established between the state and the FARC guerrillas.

CA: Do you think that artists can make an important contribution to historiography?

DS: I am a great admirer of Walter Benjamin, whose lessons in history I view as essential. What we, as historians and artists, are trying to do is to respectively recount and rewrite history from our present perspective. Our mission as artists is to revisit the past; there is something messianic in this act of rewriting. I felt this for example on the day we laid out Sumando Ausencias on Plaza de Bolívar in 2016. I felt as if a messianic act had been performed, as W. Benjamin would say. He wrote that we – and each generation – have been endowed with a weak messianic power and, on that day, we exercised that weak power to conjure up the idea of salvation. For W. Benjamin, this meant that a new image could have the power to strike down an image of the past right before our eyes. At that very moment, in a moment of danger, if we do not appropriate that image and fail to present it, then it can become lost to us forever.

González Fernán, Poder y Violencia en Colombia, Bogota, ODECOFI-CINEP, 2014. See also, González Fernán, “No Estamos Condenados Ni a la Guerra ni a la Violencia”, Semana, 29 August 2015, https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/fernan-gonzalez-habla-de-su-libro-el-conflicto-la-paz/440390-3/.

2

Following the negative response to the referendum that aimed to ratify a peace accord between the state and the FARC, D. Salcedo and hundreds of collaborators created Sumando Ausencias on 12 October 2016. The piece consisted in covering the entire Plaza de Bolívar in 7 kilometres of white fabric, stitched together and spelling out the names of victims written in ashes. After a wave of demonstrations and under international pressure, in November 2016 the accord was signed despite the vote.

3

Deleuze Gilles, and Guattari Felix, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Carolina Ariza is a curator and researcher. In 2018 she defended a PhD thesis in arts at Université Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne about the artistic resurgences of “little” histories in Colombia, starting with the storming of the Bogota courthouse in 1985. In 2019 she was a finalist of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques’ (CNAP) theoretician and art critic research grant for the development of the publication and exhibition project Tisseuses de mémoire. Les artistes femmes et leur participation à l’écriture de l’histoire [Memory weavers: Women artists and their involvement in writing history]. She curated the exhibitions Tisseuses de mémoire (Espace Arte Faktos, Paris, 2019) and Murmures et visions. Une déambulation en Amérique latine (IESA arts & culture, Paris, 2016), and was in charge of the Latin American section of the Solo Projects at the SWAB Art Fair in Barcelona (2014 and 2015). She also worked as a research supervisor in the Latin American department of the Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou for the project Recherche et mondialisation, and took part in the museum’s acquisition of Antonio Caro’s piece Aquínocabeelarte [Artdoesnotfithere, 1972].

Doris Salcedo & Carolina Ariza, "Doris Salcedo: From Singular Identity to Collective Historiography." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/doris-salcedo-de-lidentite-singuliere-a-lhistoriographie-collective/. Accessed 16 February 2026