Research

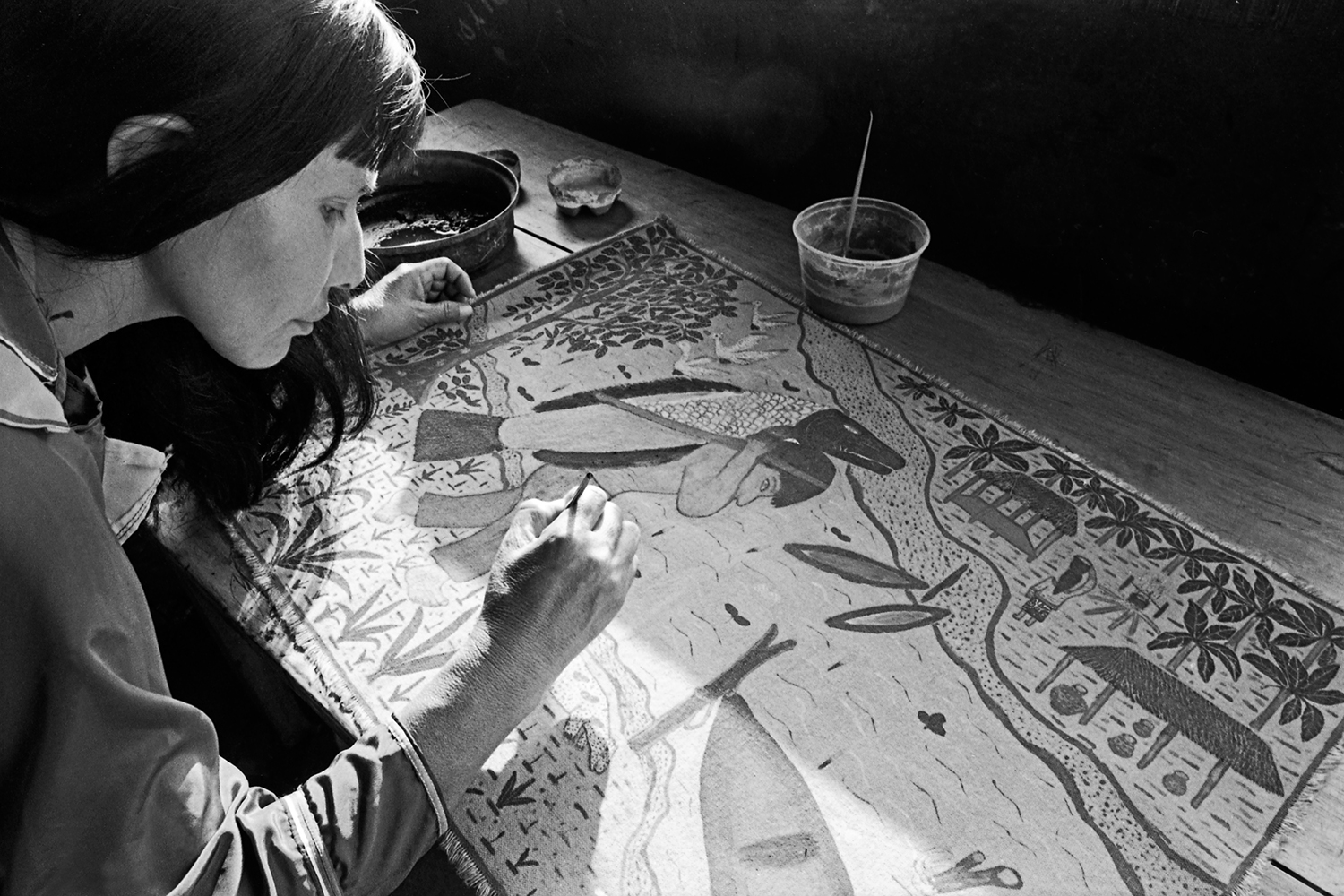

Mónica Newton, Asi es mi pueblo, Elena Valera, Cantagallo, Lima [This is my town, Elena Valera, Cantagallo, Lima], 2004, digital printing on photo paper, 20 x 30 cm

The trajectory of Shipibo-Konibo painter Elena Valera (Bawan Jisbe, b. 1968) helps us reflect on a series of important changes in the Peruvian art scene’s political frontiers in recent decades. Through historian Pablo Macera’s invitation, E. Valera trained at the Seminario de Historia Rural Andina (the Andean Rural History Seminar), or SHRA workshops in 1998. The SHRA was a project of the National University of San Marcos, founded by Macera in 1966 to challenge structures of colonial domination through research, art and literature. In the 1970s the SHRA initiated an academic rescue of Amazonian history through the publication of historical documents such as La memoria sobre el Amazonas peruanos [The Memory of the Peruvian Amazon] (1966) by David Muñoz but also of new research, for example, La explotación del caucho en Perú [Rubber exploitation in Peru] (1977) by José Flores Marín. In 1997 a second phase of action began with the reactivation of the SHRA’s research focus on the traditions of Amazonia, which sought to emphasise oral histories, bilingual narratives, and the role of art in the transmission of collective memory. Under Macera’s direction and María Belén Soria’s coordination, this new phase began to promote collaborations with indigenous narrators and painters who had slowly begun to modify Peru’s art scene’s vocabulary of cultural discussion.

One of the most significant aspects of the SHRA’s work was its desire to position the Amazonian arts and demand that their value be understood from a different perspective from the one established by dominant Western aesthetics. Macera established close ties with indigenous painters such as Víctor Charay, Enrique Casanto and Lastenia Canayo (Pecon Quena), generating their enthusiasm for publicly sharing their work that narrated their personal stories and recounted their communities’ perspectives of the world. The SHRA organised intercultural workshops aimed at fostering the creative force of indigenous artists, who were invited to write and illustrate books about Amazonia’s history and present their art in exhibitions at the San Marcos Museum of Art or the Museum of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru. These works challenged a system of artistic meaning anchored in the standards of the fine arts, as well as the hierarchies of race and class that dominated Lima’s art scene. María Belén Soria recounts the hostility of the local cultural establishment at the end of the 1990s that saw indigenous art as handicraft with little value: “This criterion reflected the established difference, since the time of the Enlightenment, between notions of ‘academic culture’ and ‘popular culture’, which reserved for the former the monopoly of the reproduction of beauty, while judging the latter as the result of intellectual dullness and the vulgarity of the customs of the riff-raff.”1

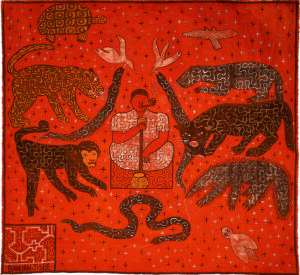

Elena Valera (Bawan Jisbe), Visiones del chamán [Shaman’s vision], 1999, Courtesy of Gredna Landolt.

Before participating in the SHRA workshops, E. Valera attended nursing school but was forced to drop out due to limited financial means. Like other self-taught indigenous painters, she strengthened her artistic identity through the exchanges she had within the SHRA. Her early paintings document visions from ayahuasca, myths of Amazonia, and the kinship that exists between land, the spiritual world and human beings from the Shipibo perspective. E. Valera’s Visiones del chamán [Shaman’s vision] (1999) is made with natural dyes on canvas and represents a shaman smoking tobacco surrounded by a monkey, a puma, a turtle, various serpents and other animals, covered by various kené designs. As the painter describes it: “When I paint, I feel that I am present within my own world, it’s as if I am feeling myself. (…) I like for them to know about my people, about who they are, and the place we inhabit, over there, in the jungle. (…) The plants have their own power, so you feel another type of air, another force. That is what I want to share in my painting, to make them feel how I feel in that moment.”2 As researcher Gredna Landolt points out, the care E. Valera takes in portraying animals and other beings derives from the respect she feels for them “in their condition as kin to humanity, as possessing a soul”.3

E. Valera was part of one of the 14 founding families of Cantagallo, a Shipibo-Konibo community that settled on a vacant lot on the banks of the Rimac river in 2000, a few blocks from Lima’s historic centre. The majority of the families began migrating from Amazonia to Lima in the mid-1990s. During those years, women took on the leadership of several of the main associations within the community. E. Valera was elected president of Ashirel [Association of Shipibo Artisans Residing in Lima] in 2007, which meant a great deal of political responsibility that had a significant impact on her and her family life and the time she could devote to her artistic production. Today, Cantagallo is the largest indigenous urban settlement in Peru, and, despite having become a leading public voice, the residents are still struggling to acquire land titles and access to basic services such as water and sewage. Many of E. Valera’s paintings from those years narrate the difficulties of migration the Shipibo community faced, the racism and discrimination in Lima, and the ways in which her community fought to maintain their roots and traditions in the city.

E. Valera’s work was gradually integrated into Lima’s art scene. Those who bought her work also evolved over time: in the late 1990s her buyers were mainly historians and anthropologists; later it was artists and curators, followed by contemporary art collectors. The art scene itself underwent transformations due to the neoliberal politics introduced during Alberto Fujimori’s dictatorship. The fall of the latter in November 2000 signalled a return to democracy but this time embraced by a neoliberal model in which art became assimilated into the discourse of the corporate art market.

Like the work of other indigenous artists, E. Valera’s paintings require a different analytical framework from the one used by the fine arts. She did not conceive her work with professional development in mind, as it is often taught in universities. The Western concept of “art” does not exist in the Shipibo world; rather, the Shipibo talk of kené which means “design”. Kené is the name given to the geometric patterns usually traced by women on ceramics, textiles, paintings, objects and human skin. These patterns give structure and materialise the energy of master plants and present a different understanding of time and space in which human life, nature, land and spiritual beings exist in reciprocity. Like other Shipibo women, E. Valera learned to trace kené with her mother and grandmother. It is not learned through copying a drawing, but rather, surges from the intimate relationship with the energy of the plants and the visions induced by ayahuasca and piri-piri.4 In her paintings, kené usually appears on the skin of her figures, which include serpents, mermaids, river dolphins and shamans. She even signs her name on her work in the form of a geometric design.

Elena Valera (Bawan Jisbe), La lucha de los Shipibos frente al covid-19 en la Comunidad Shipibo-Konibo en Cantagallo [The Shipibo fight against covid-19 in the Shipibo-Konibo Community in Cantagallo], 2022, natural pigments on canvas, © photo: Miguel A. López

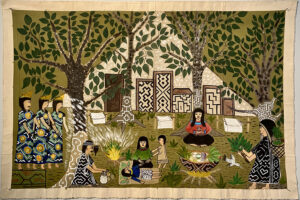

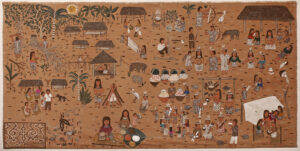

Soon after she began painting in 1999, her work was included in El Laberinto de la Choledad [The Labyrinth of Choledad], an exhibition that presented a panorama of the visual arts in Peru from 1979 through 1999 curated by the Asociación Espacios y Márgenes. Her work was also exhibited in Telas pintadas shipibas. Roldán Pinedo y Elena Valera [Painted Shipibo Canvases: Roldán Pinedo and Elena Valera], curated by Soria in the Popular Art Temporary Exhibition Gallery in the San Marcos Museum of Art. In 2000 her work was included in the ambitious exhibition of several cultural objects from different Amazonian nations titled El ojo verde. Cosmovisiones amazónicas [The Green Eye. Amazonian Worldviews], curated by Macera and Landolt in the Sala Fundación Telefónica.5 Later exhibitions sought to place E. Valera’s painting on equal footing with Western art forms and contemporary art. Of particular importance are the La soga de los muertos: el conocer desconocido de la ayahuasca [The Noose of the Dead: The Unknown Knowledge of Ayahuasca] exhibition curated by Christian Bendayán at the Museo de Arte de San Marcos in 2005 and the “Entornos reconfigurados” [Reconfigurated Surroundings] section curated by Gabriela Germaná for the LIMA 04 exhibition at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC), Lima in 2013.6 These curatorial practices demanded the recognition of the political value of indigenous voices in the face of the dominant white and urban discourse.7 Although Valera has gradually stopped painting to practice traditional, indigenous medicine, her work has continued to circulate in different spaces. They have impacted the way in which museums see their collections, their narratives, and categories. In 2018 the MAC Lima acquired her painting, La gran fiesta del Ani Sheati [The Great Ani Sheati Party] (2005), making her the first indigenous Shipibo artist to enter their contemporary art collection.

Elena Valera (Bawan Jisbe), La gran fiesta del Ani Sheati [The Great Ani Sheati Party], 2005, natural pigments on canvas, 89 x 181.5 cm, museo de Arte de Lima, © Photo: Daniel Giannoni

Another effect of E. Valera’s painting has been to pave the way for others from Cantagallo to access various spaces in the cultural scene (craft fairs, commercial galleries and museums, among others), especially for women who are the ones to traditionally draw kené. As kené is the embodiment of visions from shamanic and ritual use of master plants, women – unlike men – are more active in offering the public an aesthetic materialisation of energy and protective spirits. As researcher Luisa Elvira Belaúnde points out, the intimate link between women and kené also means a “certain material aesthetic dependence of men on women” since all male clothing and objects used daily “are adorned with kené by women”, that is, “without a woman, a man would have no material adornment”.8 Women have also assumed a key role in the production and sale of artistic and handicraft objects with kené that allow the economic sustenance of many Shipibo families, sometimes earning more money than the men. The commercialisation of paintings, embroidery and objects is also an extension of the spaces where their voices can have a political impact. In recent years several women artists from Cantagallo have begun to gain significant visibility, among them Olinda Silvano (Reshinjabe), Wilma Maynas Inuma, Silvia Ricopa, Delia Pizarro, Cordelia Sánchez (Pesin Kate), Metsá Rama and the Shipibo Collective. Many of them have created huge murals in different parts of Lima, theatrical works and musical concerts through their chants, which have a performative therapeutic dimension – the energy of kené is interpreted by the women through a musical reading of the different geometric patterns and designs. This makes it clear that kené is not only an aesthetic art form but also science, medicine, philosophy and ecology.

At the end of the 1990s, E. Valera’s appearance on Lima’s art scene led to a different way of thinking and relating to the world, even when they weren’t always well-received. In the face of the homogenisation channelled by that decade’s neoliberal modernisation, her paintings offered forms of resistance to the dispossession, demanding the value of the knowledge that emerges from plants and reminding us of the importance of living in reciprocity with the land we inhabit. E. Valera’s creations and the new generation of artists are part of the struggles that are freeing the Shipibo-Konibo people. Through their art and activism, these artists demand the preservation and respect of their ancestral knowledge and the prevention of the destruction of the Amazon to improve the living conditions of indigenous peoples in Peru and elsewhere.

María Belén Soria, “La Amazonía en el quehacer del Seminario de Historia Rural Andina (1977-2015)” [Amazonia in the work of the Seminar of Andean Rural History (1977-2015)], ISHRA. Revista del Instituto de Historia Rural Andina 1, no. 1 (July-December, 2016): p. 105.

2

Elena Valera, “Cuando pinto siento…” [When I paint, I feel…], in Amazonía al descubierto. Dueños, costumbres y visiones (folleto de exposición) [The Amazon uncovered: spirit guides, customs and visions] (exhibition brochure, Lima: Museo de Arte del Centro Cultural de San Marcos, 2005).

3

Gredna Landolt, “Es nuestra costumbre. Shoyan Sheca y Bahuan Jisbe, del pueblo Shipibo” [It is our Custom. Shoyan Sheca and Bahaun Jisbe, from the Shipibo community”], in Amazonía al descubierto, ibid.

4

See Luisa Elvira Belaúnde, Kené: arte, ciencia y tradición en diseño [Kené: Art, Science, and Tradition in Design], Lima: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 2009.

5

Pablo Macera and Gredna Landolt, El ojo verde: cosmovisiones amazónicas [The Green Eye: Amazonia Worldviews] (ima: Programa de Formación de Maestros Bilingües, AIDESEP, Fundación Telefónica, 2004).

6

Ver Christian Bendayán, La soga de los muertos: el conocer desconocido de la ayahuasca [The Noose of the Dead: The Unknown Knowledge of Ayahuasca] (Lima: Centro Cultural del Museo de San Marcos, 2006); and Gabriela Germaná, “Entornos reconfigurados: tránsitos artísticos en la nueva contemporaneidad limeña” [Reconfigured Surroundings: Artistic Transits in Lima’s New Contemporaneity], in Lima 04 (Lima: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima, 2013), pp. 36-57.

7

Additional reflections can be read in María Eugenia Yllia’s “Ensanchar las fronteras invisibles: las artistas indígenas, campesinas y rurales en Perú” [Widening the Invisible Borders: Indigenous Artists and Rural Farmers in Peru], in Hay algo incomestible en la garganta. Poéticas antipatriarcales y nueva escena en los años noventa [Antipatriarchal Poetics and the New Scene in the 1990s], ed. Miguel A. López (Lima: ICPNA, 2021), pp. 226-236, y Giuliana Vidarte, “Equilibrio, convivencia y protección de territorios y saberes en la obra de dos artistas del pueblo Shipibo-Konibo: Elena Valera y Chonon Bensho” [Harmony, Coexistence, and Protection of Land and Knowledge in the Work of Two of the Shipibo-Konibo Community: Elena Valera and Chonon Bensho], in Hilo común / Common Thread, ed. Miguel A. López (San Diego, CA: INSITE, 2023).

8

Belaúnde, Kenét, p. 22.

Miguel A. López is a writer and curator. In his practice, he focuses on the role of art in politics and public life, collective work and collaborative dynamics, and queer and feminist rewritings of history. From 2015 to 2020 he worked as chief curator, and later co-director at TEOR/éTica, Costa Rica. In 2019 he curated the retrospective Cecilia Vicuña: Seehearing the Enlightened Failure at the Witte de With (now Kunstinstituut Melly), Rotterdam. He is the curator for the 2024 edition of the Toronto Biennial of Art.

An article produced as part of “The Origin of Others” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

Miguel A. López, "Elena Valera (Bawan Jisbe): Painting Reciprocity with the Land." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/elena-valera-bawan-jisbe-peindre-la-reciprocite-avec-le-territoire/. Accessed 6 February 2026