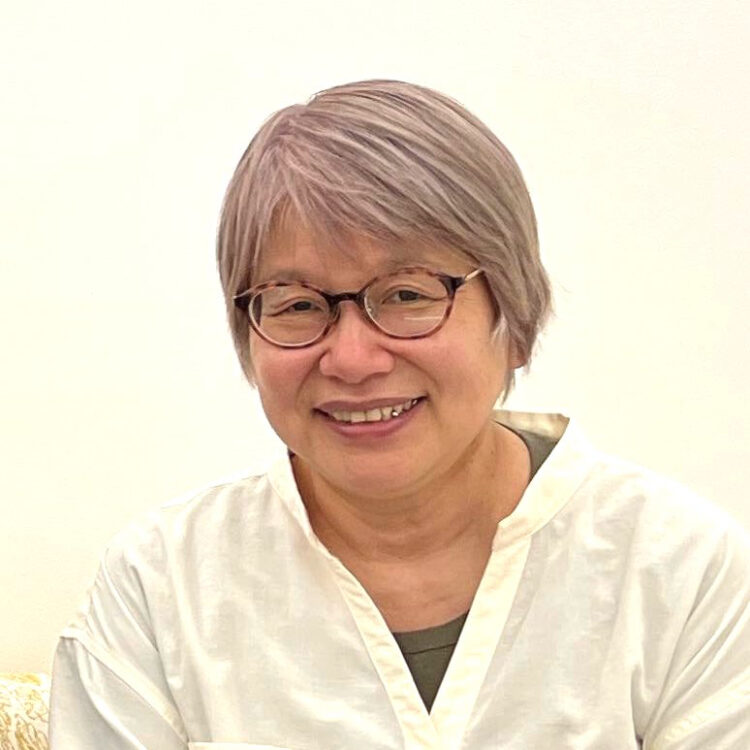

Haruko Hasegawa

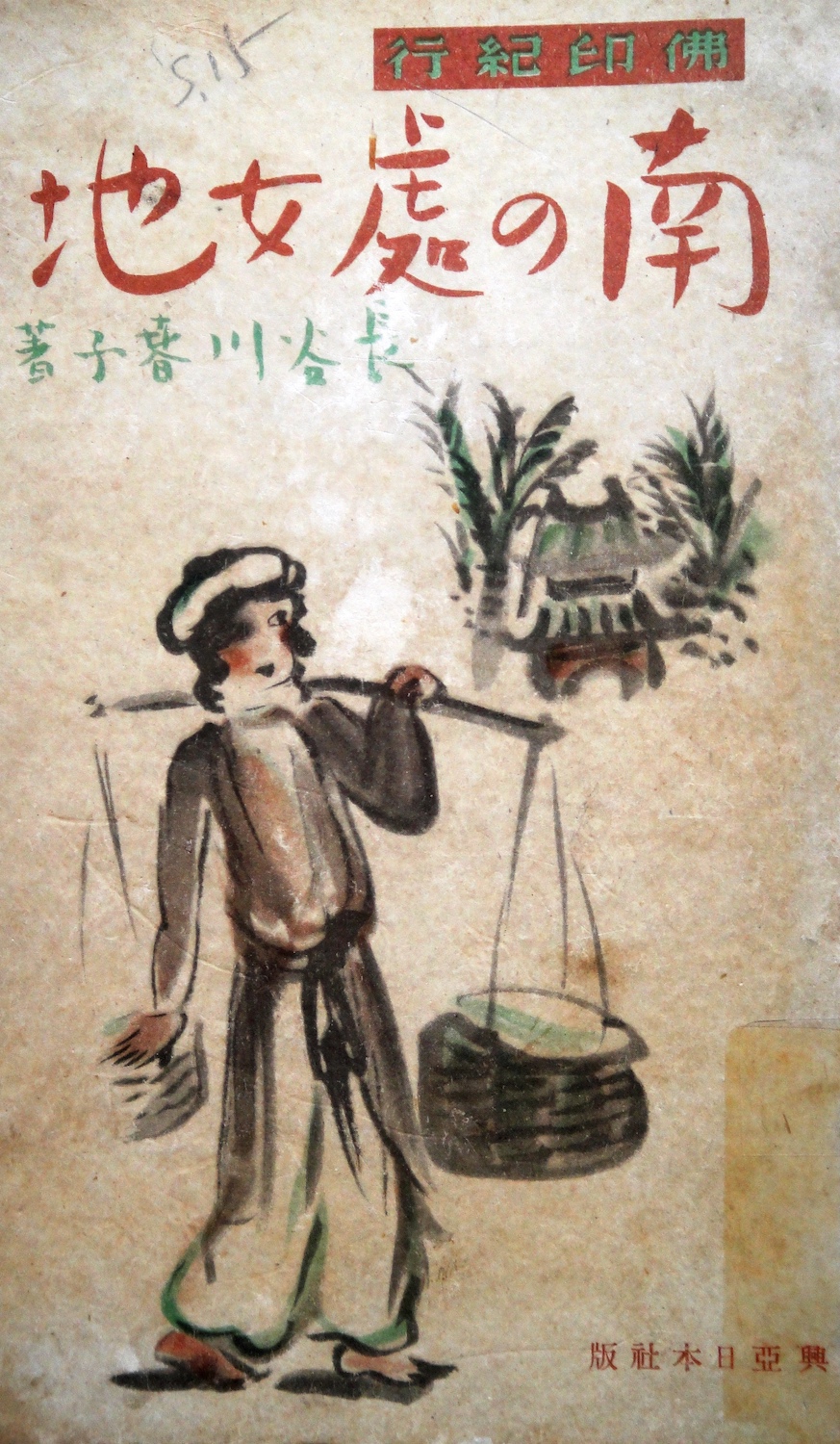

Hasegawa, Haruko, Minami no Shojochi [Virgin soil of the south], Koua Nippon Sha, Tokyo, 1940

→Hasegawa, Haruko, Hokushi mōkyō sensen: E to Bun [The Battle Lines of Northern China and Inner Mongol: Drawings and Texts], Akatsuki shobō, Tokyo, 1939

→Hasegawa, Haruko, Manchiukū [Manchukuo], Mikasa Shobō, Tokyo, 1935

Exhibition of Fighting Teenage Soldiers, Tokyo Mitsukoshi Departmentstore, Tokyo, September 1943 (travelled from Tokyo to Kobe, Osaka, Kyoto and other japanese cities)

→Hasegawa Haruko: Works, Marunouchi Teiseki Gallery, Tokyo, June 1943

→The 6th Exhibition of the Society for National Painting, Tokyofu Art Museum, Tokyo, April 1931

Japanese artist.

Haruko Hasegawa was a female painter who visited war zones in Manchuria, Mongolia, South China and French Indochina in the 1930s and 1940s, and conveyed the “achievements” of the Japanese military through her stylish writing and paintings, while at the same time playing an active role in the network connecting female artists in Japan. Although she published six monographs before the war and left behind not only her paintings but also much written material, she was rapidly forgotten in post-war society.

H. Hasegawa was born in 1895 in Tokyo, the youngest of seven siblings to a lawyer father. After graduating from Futaba High School for Girls, she studied Japanese painting under Kiyokata Kaburaki (1878-1972) and oil painting under Ryuzaburo Umehara (1888-1986) to master the art of painting. She wrote and illustrated for Nyonin Geijutsu (Women’s art, 1928-1932), a magazine founded by her sister Shigure Hasegawa, and held a solo exhibition in France after moving there in 1929. On her return to Japan, she traversed the continent on the Trans-Siberian Railway, and was moved by a glimpse of Manchukuo which was about to be established. The following year, in 1932, with the cooperation of the Japanese military, H. Hasegawa travelled to Dalian, Hsinking, Mukden, Harbin, Inner Mongolia and other places, capturing in pictures and writing the tense situation in north-eastern China, which was changing under the control of Japanese government.

After returning to Japan from her trip, H. Hasegawa joined the Kokugakai, the Society for National Painting, and had a solo exhibition, and worked energetically on her art. From the 1920s to 1930s the popularisation of art in Japan was in full swing. She and other women painters formed groups of women painters such as Nanasai Kai to support each other in the face of inequality and male dominance in the art education system and in the presentation of works.

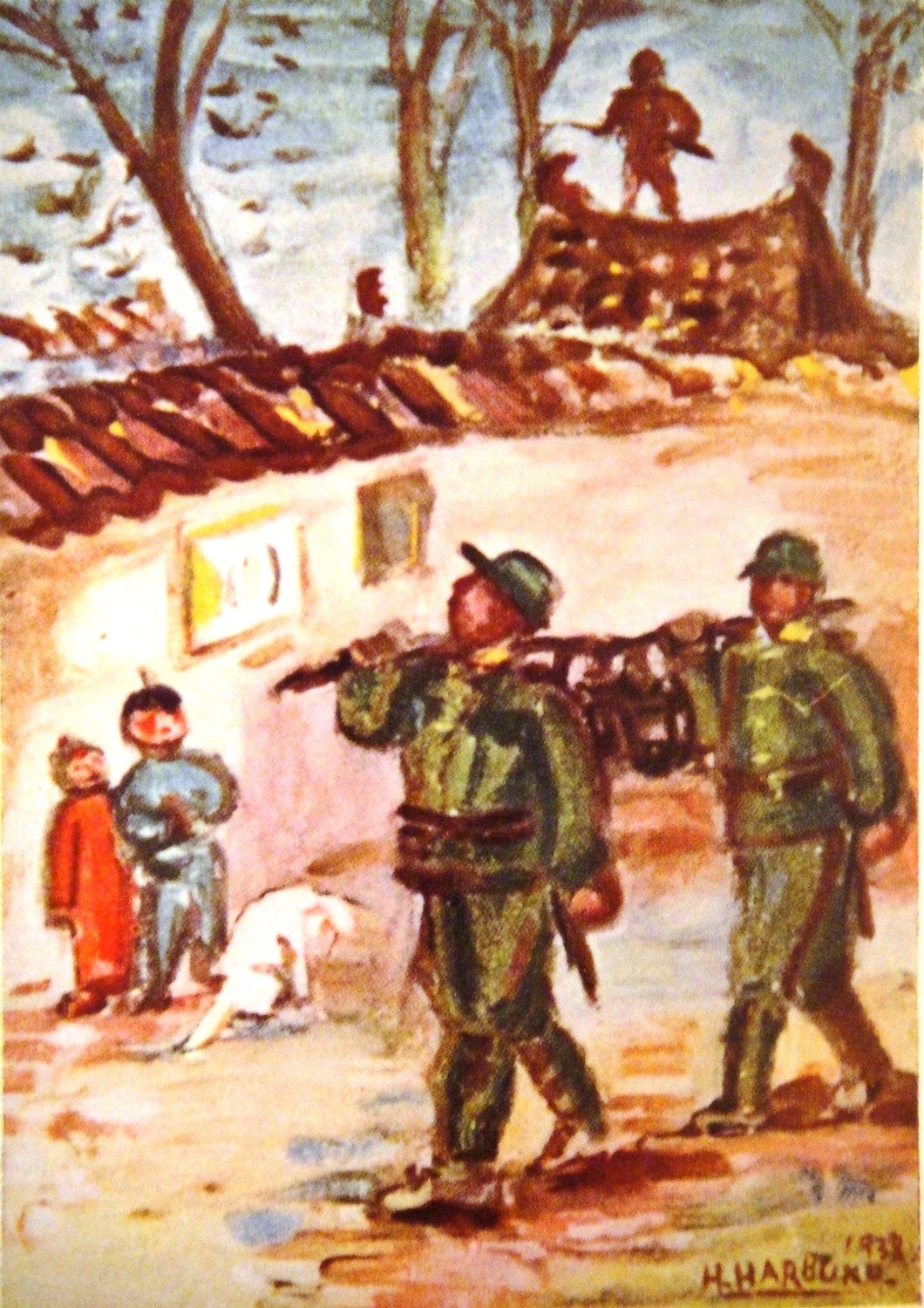

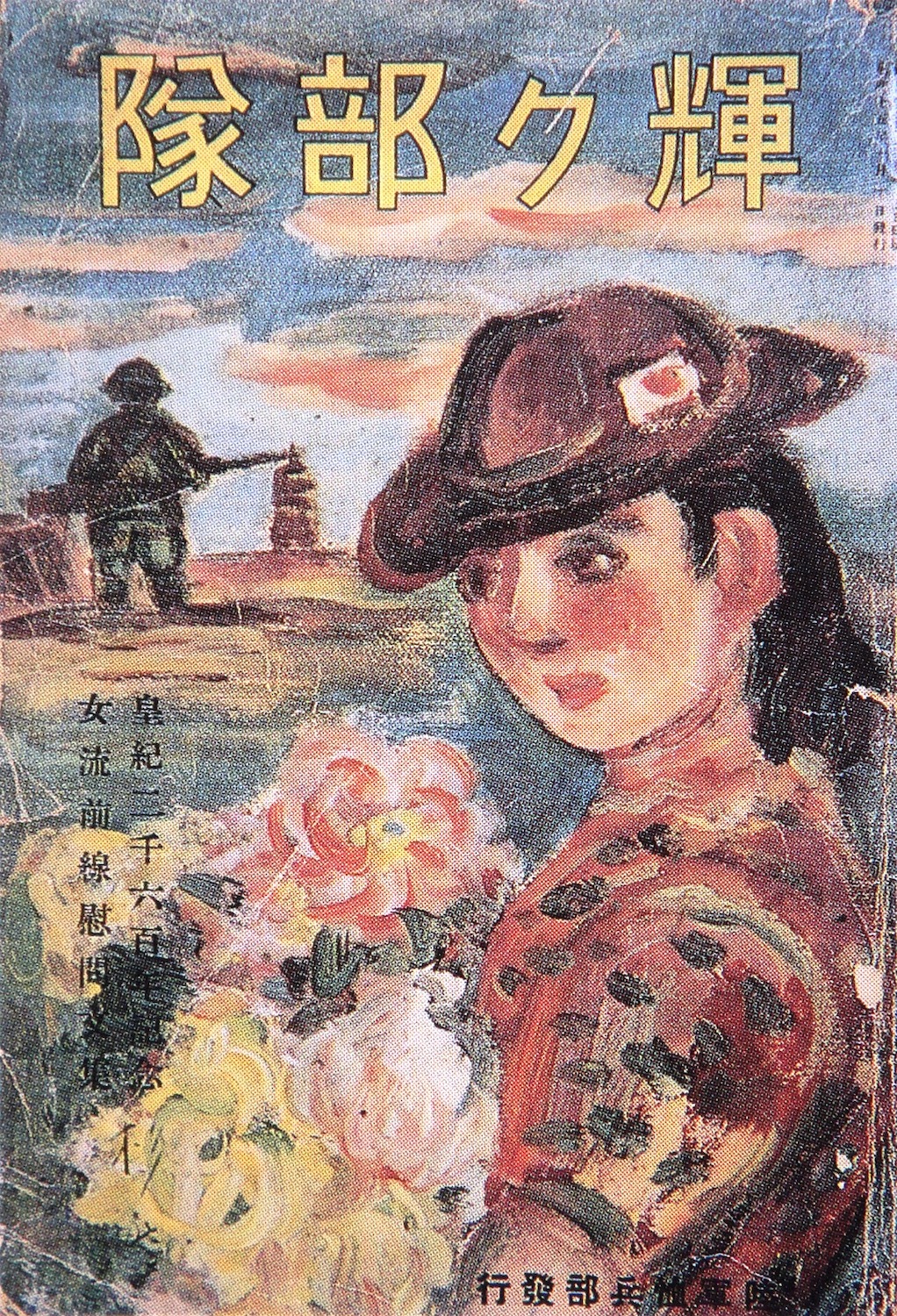

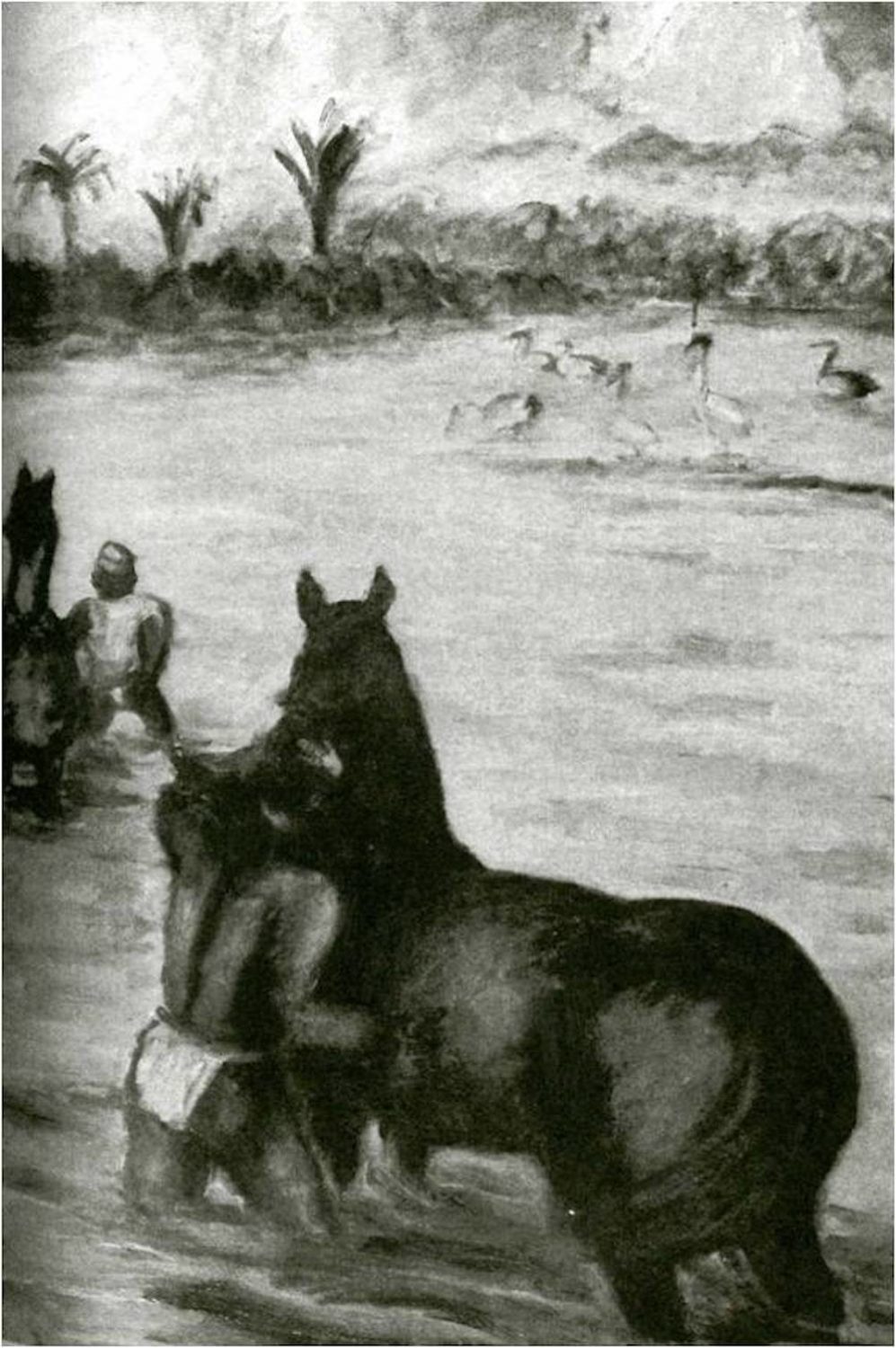

When the Sino-Japanese War began, H. Hasegawa immediately went to northern China and Mongolia as a special correspondent for newspapers and magazines, wearing pants with a pistol slung over her shoulder. The record of her service at this time was compiled in Hokushi Moukyō sensen (The battle lines of Northern China and Inner Mongol, the front in North China and Mongolia, 1939). In 1938 when the Association of Great Japanese Army Painters was formed, she was the only woman to be named as one of its founders and exhibited Dawn on the Battlefield (1938) and other war paintings at its first exhibition. Soon after, in 1939, she was sent by the War Department to southern China, Hainan Island and French Indochina (The Virgin Soil of the South, 1940). These experiences were published in a series of magazine articles and in exhibitions such as Exhibition of the Art of the Holy War and Exhibition of Army Art.

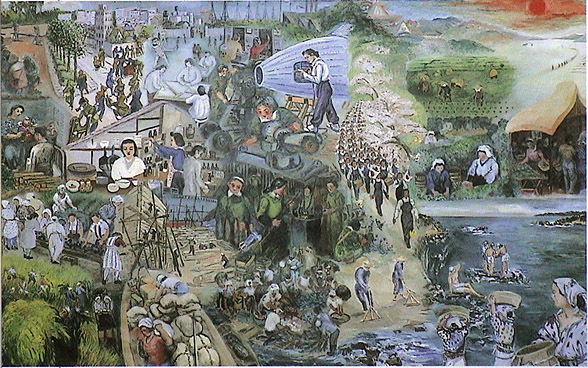

In 1943, in the middle of the Asia-Pacific War, H. Hasegawa herself became the chairperson of the Women Artists’ Public Service Brigade, which was formed with about 50 women artists, and actively promoted the home-front war cooperation. The Women’s Artist Corps was commissioned by the War Department to produce a major work on the theme of women of the home front who work on behalf of men in the war zone, Daitōwa sen kōkoku fujo kaidō no zu (Pictures of Imperial Japanese women working together for the Greater East Asia War, 1943).

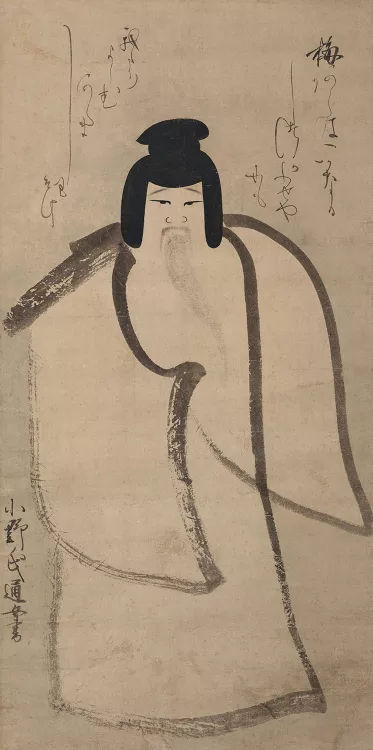

After the war women painters formed a new group and began their activities, to which H. Hasegawa did not join. She extensively drew illustrations for newspaper novels and columns, and in her later years she devoted herself to her life’s work, 54 picture scrolls of The Tale of Genji.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022