Research

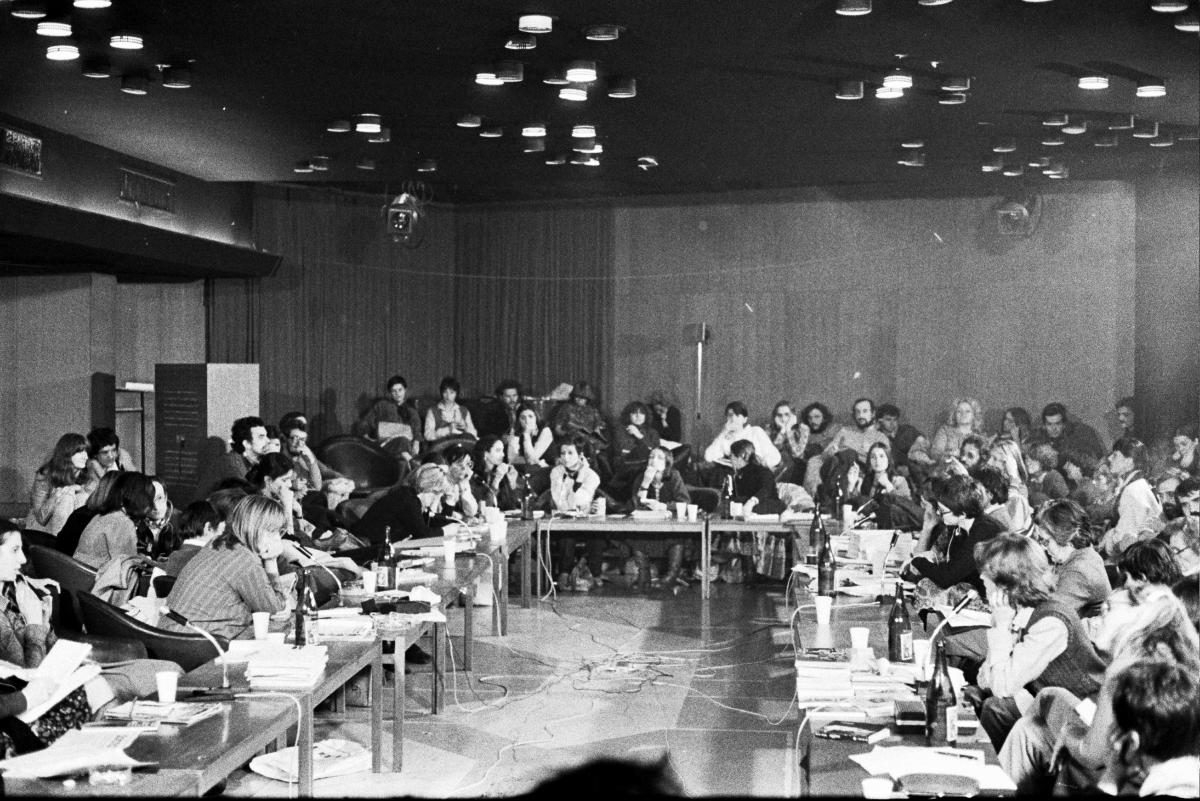

Conference Drug-ca žena: Žensko pitanje – novi pristup? [Comrade Woman: Women’s Question – A New Approach?], Belgrade, Student Cultural Centre (SKC), 1978 © SKC Belgrade Archive

On the contemporary art scenes of the countries of post-socialist-Yugoslavia there is consensus on the historical significance of art historian, curator and critic Dunja Blažević. Her experiments in broadening institutional space for New Art Practices1 have been researched and interpreted in projects, exhibitions and papers over the last ten years.2 Already in the 1970s Blažević used the term applied critique in reference to her own work. The term suggests her constant search for innovation in art, the democratisation of this narrow and elite field, and an art that would find its place and function in the self-managed socialist society. Although thoroughly researched, little has been published on the feminist aspect of her curatorial experiments, despite its continuity from the very beginnings of her career.

Throughout her professional life, Blažević held four institutional positions, in three different institutions and under two different political and economic systems. At the age of 26 she was curator and editor of the visual program of the Gallery of the Student Cultural Centre (SKC) in Belgrade (1970-1976), then director of the SKC (1976-1979), then editor-in-chief of the visual arts programme at TV Belgrade (1980-1991), and finally director of the Sarajevo Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA, 1996-2010). In all these positions she initiated and organised explicitly feminist programs, open discussions on women’s position in art and society in general, as well as supporting female artists, expanding spaces for production, exhibiting and mediation in an unprecedented way.

The first feminist program she organised was the discussion “Women in Art” at the SKC in 1975, within the framework of the fourth edition of the April Meetings, an extended media festival. It gathered female artists, art historians and critics, as well as feminist activists from different geographies and political-economic systems: Western capitalist and Eastern socialist countries, such as Nena Baljković Dimitrijević, Ida Biard, Iole de Freitas, Natalia LL, Gislind Nabakowski, Ulrike Rosenbach, Katharina Sieverding, Irina Subotić, Jasna Tijardović, Biljana Tomić and Jadranka Vinterhalter. With hindsight, and relying on post-socialist feminist scholars such as Chiara Bonfiglioli, Adrijana Zaharijević and Kristen R. Ghodsee who insist on different feminist temporalities in East and West, this event called for focused attention and further research.

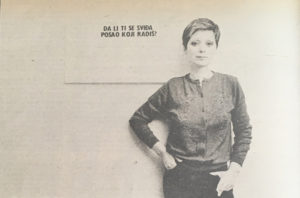

“Dunja Blažević: Aktivistkinje avangarde” [Dunja Blažević: The activist of the avant-garde], an interview with Vesna Kesić, Start 340 (February 12, 1982), pp. 48-49

Not only was it one of the first feminist interventions in art in the context of socialist Yugoslavia, but its composite structure can be seen as a foundation for the 1978 event Drug-ca žena: Žensko pitanje – novi pristup? [Comrade Woman: Women’s Question – A New Approach?] which is “still considered a landmark of feminist history in the former Yugoslavia”.3 This paradigmatic event was the first autonomous second wave feminist conference in a socialist country. It was initiated by young scholars and feminists, Nada Ler Sofronić and Žarana Papić, and curated together with Blažević. As Bonfiglioli’s feminist oral history project on the event has demonstrated, Blažević’s made SKC available for this and other feminist meetings.4 In a somewhat modest tone, Blažević recollects the first steps: “They [Ler Sofronić and Papić] had read feminist theory, and engaged with feminism internationally.[…] I have become a feminist somehow by nature.”5 The conference gathered feminists from both Western capitalist and Eastern socialist countries for the first time and was structured around three thematic threads: 1) woman, capitalism, social change; 2) woman, culture; 3) woman, capitalism, revolution. As these titles suggest, women’s questions were seen as inseparable from social organisation, and women’s emancipation was considered as going hand in hand with overthrowing capitalism. Somewhat surprisingly, although focused on the socio-political context and openly critical of capitalism, it avoided themes dealing with socialism, up until the closing session titled “Position(s) of Woman in the Self-Managed Socialist Society”. According to Bonfiglioli, the aim of this particular session was to develop a feminist critique of the socialist state’s gender politics in Marxist terms. The idea was not to dismiss the material and legal achievements of socialism with regards to the so-called “women’s question”, but to criticise patriarchy in a socialist state as a bourgeois residue and therefore an obvious contradiction of it: “This internal critique of the Yugoslav system – feminist but not anti-socialist – is a very specific one, and represents, in my view, the major point of cultural and political difference between the Yugoslav and the international participants, the knot that can only be translated with difficulty.”6

An exhibition programme at the SKC gallery accompanying conference was curated by B. Tomić and D. Blažević, with the assistance of Bojana Pejić. It comprised two documentary art exhibitions dedicated to Claire Bretécher and Goranka Matić: Jugoslovenska žena u statistici [The Yugoslav woman in statistics] and Seksizam oko nas [The sexism that surrounds us]. Both shows displayed data collected from official statistics and state media outlining the position of women in Yugoslav society, alongside film and video programmes. This event shook the political establishment and provoked heated public debates. Looking at it from a wider perspective, it appears as another schism between the “official” and “alternative” spheres, in this case between gender politics of the state and autonomous feminism. Both of these conflicts traverse the entirety of Blažević’s career.

In a later text, “Da li žensko pitanje još postoji?” [Does the woman’s question still exist?], in which she looks back at the Drug-ca žena event, she concludes with a focus on the position of female artists: “A precondition for dealing with that phenomenon is the existence of the feminist critique and theory, which in our context remains non-existent, or comes down to a few individuals. On the other side, female artists do not declare themselves as feminists, even though by their behaviour and their artworks they certainly are.”7 The publication of this text included a manifesto originally written with a group of female artists in Sarajevo in 2003 as a response to female artists being left without any spaces to work. The publication of the manifesto almost ten years after it was first disseminated not only underlined its relevance, but connected it to historical struggles and to her lifelong political engagement. It also showed her commitment to post-war Sarajevo, where SCCA with Blažević at the head became a single meeting point, to use the title of her first exhibition in the city, in 1997. When she arrived in post-socialist and post-war Sarajevo to run SCCA Sarajevo, now in a different political and economic system, she gathered younger generations of artists, provided material conditions and an institutional framework for artistic interventions in the public and social space, and post-war life in general, which was “essentially reduced and impoverished in relation to pre-war – materially, institutionally and professionally”.8

Portrait of Dunja Blažević by Božica Babić, published in Saša Gavrić and Hana Stojić (eds.), Dolje ti rijeka, dolje ti pruga. Žene u Bosni i Hercegovini [Down there’s your river, down there’s your railway. Women in Bosnia and Herzegovina], Sarajevo, Buybook, 2011

This experience, particularly her close work with younger generations of artists in Sarajevo, inspired Blažević’s last project, Miraz [Dowry] in 2012, an exhibition of female artists from Sarajevo and other art centres of the former Yugoslavia, including Alma Suljević, Danica Dakić, Gordana Anđelić Galić, Maja Bajević and Šejla Kamerić from Sarajevo, Darinka Pop-Mitić, Milica Tomić and group škart from Belgrade, Dejan Habicht, Marjetica Potrč and Tanja Lažetić from Ljubljana, Kristina Leko, Renata Poljak and Sanja Iveković from Zagreb. This young and vibrant scene was predominantly female, functioning in poor material conditions, with a lack of institutional recognition and no feminist support in terms of critical writings and theoretical production. Thus the exhibition was “an image of collective memory and the burden I carry, we all carry, through space and time […] as a dowry, opening one possible reading of what we call female art”.9 Appropriated from the patriarchal tradition, the title re-signifies women’s confinement to the family, positioning them in a broader social context and making them active political subjects. Bringing together female artists from the former Yugoslavia, the exhibition not only refers to their common social and political context, but empowers their shared feminist struggles.

Blažević’s curatorial position grew out of a critique of modernism, as an alternative practice in relation to the high modernism of late socialist society. It was characterised by a constant search for democratisation of the field of art, which was still perceived as elite and bourgeois even in a self-managed socialist society, and especially by her efforts to intertwine feminism with conceptual art and its dematerialisation “as a revolutionary path to a self-managed system of free exchange and associated labour”.10 Looking back at her engaged feminist curating and her systemic interventions in art institutions, it is this aspect of her applied critique that has not been emphasised enough, despite its pioneering nature and far-reaching effects.

The term New Art Practices was introduced by art historian Ješa Denegri, who adopted the term from Catherine Millet as a common denominator for radical art practices of the mid 1960s and early 1970s, comprising of different performative and time-based artistic interventions (actions, performances, happenings, body art, experimental film and video) but also visual and concrete poetry and language-based conceptual art. See Ješa Denegri, “Art in the Past Decade”, in The New Art Practice in Yugoslavia 1966-1978, ed. Marijan Susovski (exh. cat. Zagreb: Gallery of Contemporary Art, 1978), pp. 5-12.

2

Examples include Političke prakse (post-) jugoslovenske umetnosti [Political Practices of (Post-)Yugoslav art], a research and exhibition project by Prelom Kolektiv/Belgrade, WHW/Zagreb, kuda.org/Novi Sad, and SCCA/pro.ba/Sarajevo, 2009; Jelena Vesić’s essay “SKC as a Site of Performative (Self-)Production: October 75 – Institution, Self-Organization, First-Person Speech, Collectivization”, in Život umjetnosti 91 (2012); Jelena Vesić’s project Oktobar XXX: Exposition – Symposim – Performance (2012); and Ivana Bago, “Dematerijalizacija i politizacija izložbe: Primjeri kustoske prakse kao antikapitalističke institucionalne kritike u Jugoslaviji tijekom 60-ih i 70-ih godina 20. Stoljeća”, in Radovi Instituta za povijest umjetnosti, n. 36, 2012.

3

Chiara Bonfiglioli, “Remembering the Conference ‘Comrade Woman: The Women’s Question – A New Approach?’ Thirty Years After”, MA thesis, Utrecht University, 2008, p. 5.

4

Ibid., p. 52.

5

My italics. See Branka Mihajlović, “Blažević: Izložba Marine Abramović košta koliko i budžet muzeja”, Radio Slobodna Evropa, September 14, 2019.

6

Bonfiglioli, “Remembering the Conference”, p. 57.

7

Dunja Blažević, “Da li žensko pitanje još postoji?”, in Dolje ti Rijeka, dolje ti pruga. Žene u Bosni i Hercegovini (Sarajevo: Buybook, 2011), p. 20.

8

Dunja Blažević’s curatorial statement for the very first annual exhibition project of the SCCA, Meeting Point, Sarajevo, SCCA, 1997.

9

Nada Salom, “Žensko nasljeđe – doprinos jednakosti”, Aljazeera (15 October 2012).

10

Dunja Blažević, “Umetnost kao forma svojinske svesti”, in Oktobar 75 (Belgrade: SKC Beograd, 1975).

Vesna Vuković is a curator and researcher in the field of socially engaged art, and a PhD student at the University of Zadar’s Department of Art History, with a dissertation provisionally titled “Women’s visual art production in late socialism and feminist aesthetics: Contradictions and correlations”. As member of the Zagreb-based collective BLOK, she is active in the field of publishing, research, and an exhibition practice that intertwines art and politics. Since 2018 she has been editor of the BLOK’s book series Tendency.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Vesna Vuković, "The Feminist Dowry of Dunja Blažević." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/la-dot-feministe-de-dunja-blazevic/. Accessed 14 February 2026