Research

Lubaina Himid, The Carrot Piece, 1985, Acrylic paint on plywood, wood and cardboard, and string, Overall display dimensions variable, Tate Collection

The early 1980s ushered in a politically charged era among Black visual artists in Britain. Artists such as Eddie Chambers (b. 1960) and Keith Piper (b. 1960) became prominent in networks which were shaping cultural discourse, but key female figures such as Sonia Boyce (b. 1962) and Lubaina Himid (b. 1954) had a strong presence. The public sector was responsible for opening up equal opportunities in a political climate heavily influenced by the success of the women’s liberation movement. Many Black women had been involved in community campaigns, and the drive for equal rights and anti-racism allowed space for greater prominence. Following a 1976 report, The Arts Britain Ignores, the Arts Council made recommendations that arts organisations must allocate a minimum of 4 per cent of their budgets to ethnic or Black arts, which matched the percentage of the ethnic minority population in Britain at the time. However, despite this boost, during the 1980s only a few mainstream galleries became involved in organising group and solo exhibitions of Black women artists’ work. From 1980 to 1990 there were only eight solo exhibitions by Black women in mainstream galleries.

Lubaina Himid, Freedom And Change, 1984, plywood, fabric, mixed media, acrylic paint, 290 x 590 cm, Courtesy Lubaina Himid et Hollybush Gardens, © Photo Andy Keate

Lubaina Himid was a central figure in what became known as the British Black Arts Movement in the 1980s. It was not only her work as a practising visual artist which was of importance, but her writing and curatorial practice which was key to the visibility of Black women artists in Britain at a time when they were marginalised from group shows. Exhibitions of women artists almost exclusively featured white women, while Black art exhibitions predominantly focused on male artists. L. Himid was responsible for organising several groundbreaking exhibitions, including Five Black Women (Africa Centre, 1983), Black Woman Time Now (Battersea Arts Centre, 1983) and The Thin Black Line (Institute of Contemporary Art, 1985), which presented emerging Black and Asian women artists, providing a much-needed outlet for the public presentation of their work.

Now a household name and Turner Prize winner (in 2017), the Zanzibar-born, British-raised artist has come to be well known for her figurative paintings, often on life-size wood cut-outs, harking back to her training as a theatre set designer, which have a lightness and dynamism even when exploring questions of power and empire. The Carrot Piece (1985) depicts a white man on a unicycle attempting to lure a Black woman with a carrot, a commentary on the meagre and patronising offers being made to Black artists by art institutions.

Maud Sulter, Terpsichore (Delta Streete), 1989, from Zabat series, cibachrome print, 152 x 122 cm © Edinburgh City Art Centre, © ADAGP, Paris

Maud Sulter, Calliope, 1989, from Zabat series, cibachrome print 152 x 122 cm , © Victoria & Albert museum, © ADAGP, Paris

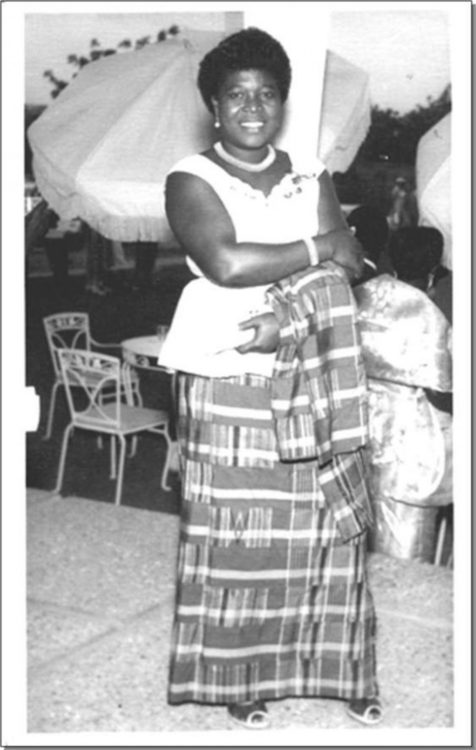

L. Himid was also a writer and publisher, setting up the Urban Fox Press along with Maud Sulter (1960-2008). Together they published Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity1, the only book produced to date in Britain dedicated to the work of Black women’s art. Sulter was a Ghanaian-Scottish writer and photographer whose portraiture served to turn art history on its head. Her series Zabat (1989) features Black women subjects styled and posed as classical muses. Sulter’s work, like that of many of her contemporaries, was rooted in collaborative practice, and she frequently featured her peers in her photographic work, including L. Himid, as well as prominent figures such as American writer Alice Walker (b. 1944).

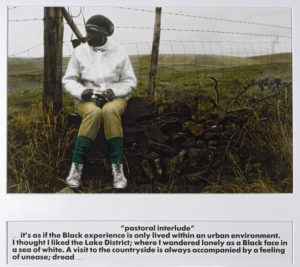

M. Sulter co-founded the Black Women’s Creative Project with Ingrid Pollard (b. 1953), another Black woman photographer associated with the British Black Arts Movement. I. Pollard’s interest in photography began as a child, and she later started to document the life of Black people in London, and more widely in Britain. Her work examines constructions of racial difference in British society. Pastoral Interlude (1987-1988) is a series of portraits set in the British countryside, questioning the commonly accepted notion that places Black people in urban rather than rural environments.

It is notable that many of the women artists associated with the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s, although they explored questions of history and Black identity, did not necessarily create explicitly political work in the way that their male contemporaries did. Sonia Boyce, whose work tells stories about the experiences of the Black woman in a white society, has expressed that she found herself under pressure from her peers to create politically explicit art, who felt it was their responsibility as Black artists to address and challenge the racism experienced by Black people in British society: “I had very definite ideas about myself and what I understood of politics… The Pan-Afrikan Connection (Herbert Art Gallery, 1983) offered a glimpse of what was possible, but I wasn’t able to work in that way.”2

Sonia Boyce, Missionary Position II, 1985, watercolour, pastel and crayon on paper, 123.8 x 183 cm, Tate Collection

Of equal importance to many Black women artists of the period, was for their work to challenge or question patriarchal ideas and behaviours. S. Boyce’s early explorations of self through monumental figurative drawings, many of which are now in national collections, are some of her best-known works. Missionary Position II (1985) ties religion together with sexual and racial politics, drawing parallels between sexual submission, and passivity towards the imposition of white culture and religion on Black people in the Caribbean.

S. Boyce’s practice over the years developed to incorporate different mediums, first photography and assemblage, before venturing into site-specific performance and installation. Other artists of the time, such as Veronica Ryan (b. 1956) had already begun making unique site-specific sculptural works. Ryan’s abstract forms cast in bronze and displayed at ground level are evocative of plant forms and other organic materials. Her public artwork Boundaries (1985, fig. 6) was displayed at Peterborough Sculpture Park, its form resembling distorted Monstera plant leaves, an unexpected contrast with its grassy location.

If it seemed like the visibility of Black women artists was improving, this was not quite the case. The decade closed with The Other Story, a major exhibition curated by artist Rasheed Araeen (b. 1935) at the Hayward Gallery of work by Asian, African and Caribbean artists. Despite the inroads made during the 1980s, the show was notable for almost completely excluding women artists; only four were exhibited out of a total of twenty-four artists – S. Boyce, Mona Hatoum (b. 1952), L. Himid and Kumiko Shimizu (b. 1948).

Ultimately funding cuts to the Arts Council and the closure of the Greater London Council impacted Black artists, and particularly Black women disproportionately. The artist Marlene Smith (b. 1964), who was also curator of the now defunct Black Art Gallery in North London in the early 1990s, noted with alarm that after the intense exhibition activities of the 1980s the number of Black women artists showing work declined. Many had lost funding during the economic recession and had to give up their studio space. The vigorous activity of the previous years left others exhausted, having spent a decade not only producing artworks, but being agents, exhibition organisers and publishers. M. Smith was not the only one to note the rapid decline at this point in time. Art historian Deborah Cherry wrote: 1989 has been seen as a turning point, marking both the demise of the Black Art Movement, and the inception of a globalised art world with the proliferation of international biennales and, in Britain, fierce debates over “the new internationalism”.3

The 1990s saw the media sensation of the young British artists, and several black male British artists became prominent, such as Chris Ofili (b. 1968) and Steve McQueen (b. 1969) who became winners of the Turner Prize in 1998 and 1999, respectively. With the exception of the same handful who found modest success during the 1980s, Black women seem to all but disappear from the British art world. The Arts Council policy changes in the 1980s may have appeared significant, but were in effect superficial. Whatever progress was made in terms of representation was not matched by the culture and structure of the funding bodies or the institutions they support. Exhibiting opportunities became far less frequent, and several of the artists mentioned sustained themselves and their creative practice by taking up teaching positionsin art colleges and universities.

The last decade has begun to see slow changes and an uncovering of the work of the women of the Black Arts Movement that has been previously obscured to anyone who is not a specialist researcher. Research and archival projects such as Making Histories Visible and Black Artists and Modernism, led by L. Himid and S. Boyce respectively, are ensuring that the artistic and intellectual legacy of this movement is solidified in British art history.

British art institutions are also finally beginning to acknowledge not only the tenacity and enduring efforts of these women, but the actual artistic value of their works, and attempting to redress the imbalances in their permanent collections and exhibiting practices.

Not only did L. Himid become the first Black woman to win the Turner Prize, she will be the subject of a major retrospective at Tate Britain in 2021. A retrospective of I. Pollard’s work will be shown at the MK Gallery in 2022, while S. Boyce has been selected as the British Pavilion artist for the Venice Biennale of the same year. Unfortunately, M. Sulter, who died in 2008, did not make it to witness this long overdue recognition, but her work and that of her peers – of whom there are too many to be mentioned in this piece – will be remembered as those who paved the way for current and future generations of Black women artists, curators and art historians.

Lubaina Humid and Maud Sulter (eds), Passion: Discourses on Blackwomen’s Creativity, London: Urban Fox Press, 1990.

2

Sonia Boyce and John Roberts (1987), ‘Sonia Boyce in conversation with John Roberts,’ Circa Art Magazine, no. 39, pp. 24.

3

Angela Dimitrakaki and Lara Perry, eds, Politics in a Glass Case: Feminism, Exhibition Cultures and Curatorial Transgressions (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013)

Aurella Yussuf is a writer and art historian. She is a founding member of interdisciplinary research collective Thick/er Black Lines and the convener of Kitchen Table Crit, a monthly salon for Black artists and writers. Her writing has appeared in Frieze, Hyperallergic, Artskop, Arts.Black and other contemporary art publications.

An article produced as part of AWARE’s academic network, TEAM: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.