Research

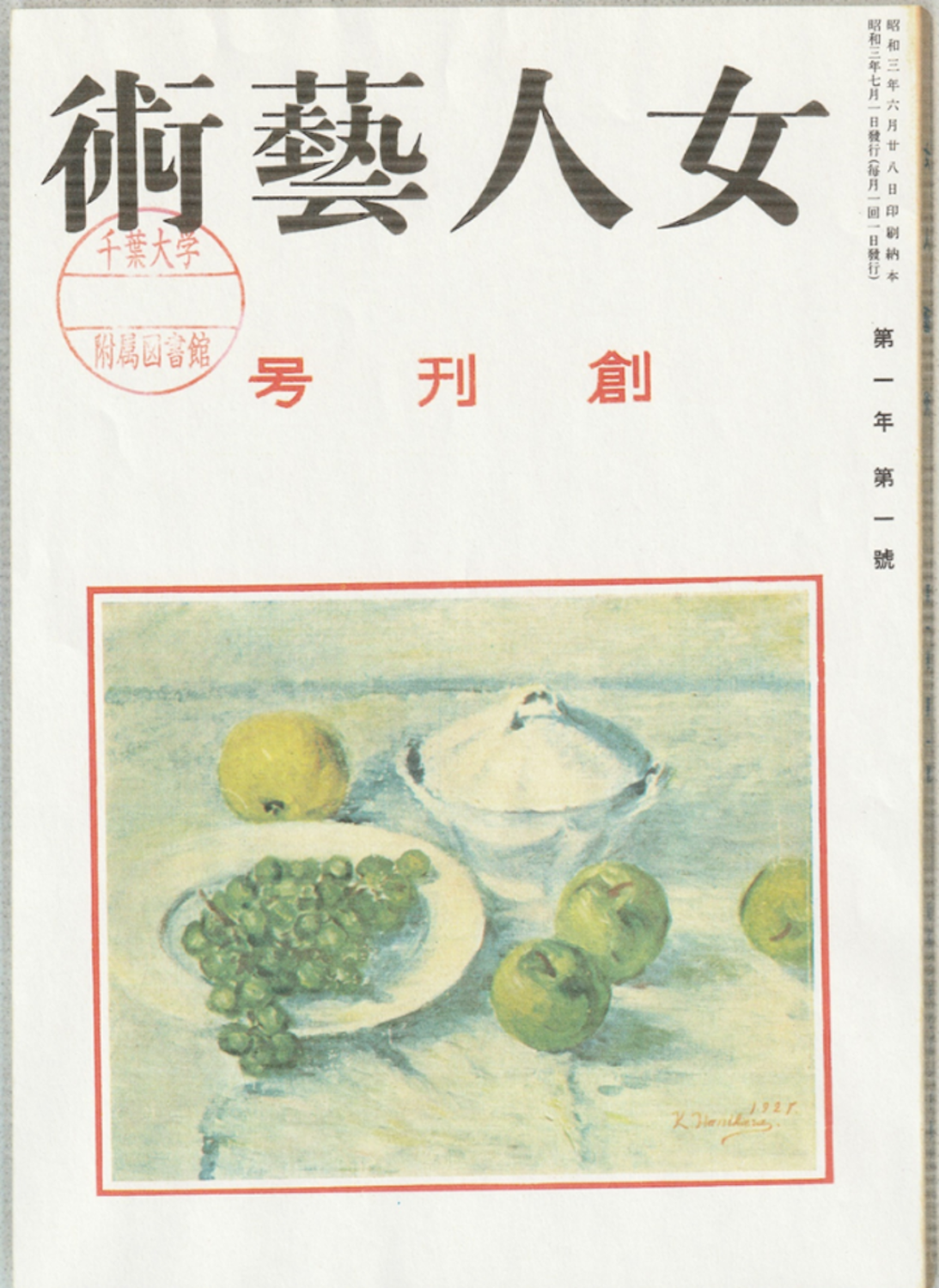

Kuwayo Hanihara, Summer Fragrance, illustration for the cover of Nyonin Geijutsu [Women’s Art], July 1928

In the period from 1868, when Japan opened to the outside world, to the end of World War II, Japanese women did not have the right to vote, had lower rates of school enrolment, and did not have the right to enrol in universities. The same was true when it came to art education. The Tokyo School of Fine Arts, a national school for the arts, was for men only.

Women themselves, however, were dissatisfied with this situation. Amongst them were the sisters Shigure Hasegawa (1879–1941), a playwright, and Haruko Hasegawa (1895–1967), a painter.

The Hasegawa sisters and their close female associates started a magazine called Nyonin Geijutsu (Women’s Art) that ran for a total of 48 issues from July 1928 to June 1932.

In this short essay, I will first explain the state of gender discrimination in politics, education and art in modern Japan, before moving on to a brief introduction to the history of Women’s Art and the cover art and illustrations drawn for it by female artists. Finally, I will offer an introduction to the role played by the Hasegawa sisters in the magazine.

Gender discrimination in politics, education and art

For Japan, modernisation meant Westernisation. The country embraced not only the technology of the West but also the structures and frameworks governing its society and culture in order to forge a modern nation-state. The view of women in pre-modern Japan was strongly influenced by Confucianism. It was believed that women were naturally stupid and could not be entrusted with the education of their children. Women were considered to be capable only of bearing these children to ensure the survival of bloodlines.

The modern era saw the birth of the philosophy of the ‘dutiful wife and devoted mother’, influenced by the Western view of gender. This would go on to become widespread starting in the 1900s. The intention behind this philosophy was to educate women to take on these new roles as members of a modern nation-state and to make them responsible for their own families. In a sense, this thinking encouraged the expansion of educational programmes for women.

It might come as something of a surprise to learn that art education was emphasised in the education of women. According to Akiko Yamazaki, from the late 1800s (Meiji 20s) to the early 1900s (Meiji 40s), male intellectuals developed the ‘theory of women’s art’, which maintained that there was a particular kind of art that was suitable for and befitting of women. The theory argued for an emphasis on the role of women as mothers and encouraged art provided it did not deviate from gender norms. This view prevented women from becoming professional artists.1 While the Private Women’s School of Fine Arts, founded in 1901, contributed greatly to modern art education for women, women’s success in the art world was the exception rather than the norm.

Artists usually showed their works at exhibitions organised by art associations and were selected for awards, rising through the ranks as they progressed from ordinary members to associates and then to full members.2 During the 1920s, however, women artists began to hold group exhibitions to push back against this state of affairs.3 Meanwhile, male art critics demanded ‘femininity’ from these exhibitions, and criticised the lack thereof. Art critics at this time were mostly male, and their criticism held sway over the output of women artists.

The birth of Women’s Art

Women’s Art was a literary magazine that first appeared in July 1928 and continued until June 1932. The magazine was led by the kabuki playwright S. Hasegawa, who limited its pool of editors and writers to women and introduced many new voices.4 The magazine’s primary goal was to discover and nurture new women writers and critics, and to promote collaborations amongst all women.5 This policy extended to the magazine’s cover art and illustrations, with Shigure’s youngest sister, the Western-style (yōga) painter H. Hasegawa, drawing on her network of women painters for contributions. As commissions for magazine and newspaper illustrations tended to be dominated by male artists, Women’s Art was one of the few media outlets that provided a venue for women artists to paint.

S. Hasegawa was born the eldest daughter of Hasegawa Shinzō, a lawyer, and Hasegawa Taki, the owner of a Japanese ryotei restaurant. After finishing elementary school, S. Hasegawa was not allowed to continue her education, as her mother believed women did not need to study. In 1897, she entered an unhappy marriage arranged by her parents, during which she began writing novels to cope with her dissatisfaction. After her divorce, S. Hasegawa wrote a kabuki script that won a newspaper competition and earned her critical acclaim, establishing her reputation as a playwright. During the Taisho period (1912–1926), she wrote seven bijinden (biographies of beautiful women), celebrating successful women, including Fumiko Kametaka (1886–1977), who was later invited to paint covers and illustrations for Women’s Art.

It was S. Hasegawa’s youngest sister, H. Hasegawa, who connected these women painters to Women’s Art. H. Hasegawa was born in Nihonbashi, Tokyo in 1895. After graduating from Futaba High School for Girls she initially assisted with her mother’s ryokan inn. At Shigure’s suggestion, she studied under renowned masters: first Japanese style painting (nihonga) under Kiyokata Kaburaki (1878–1972) and then Western-style (yōga) painting under Ryūzaburō Umehara (1888–1986). H. Hasegawa contributed not only cover art and illustrations but also essays to the magazine.

Haruko left for France in March 1929. In Paris, she devoted herself to her work, which was prolific, and prepared for a solo exhibition at the Galerie Zak in Saint-Germain-des-Près through the introduction of the painter Tsuguharu Fujita (Léonard Fujita, 1886–1968) and others. After returning to Japan in March 1931, H. Hasegawa re-engaged in Women’s Art.

Hisakayo Hanihara, Summer Fragrance, illustration for the cover of Nyonin Geijutsu [Arts féminins], July 1928

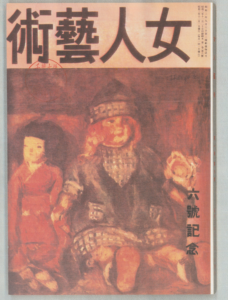

Hitoyo Kai, Mutsumi, illustration for the cover of Nyonin Geijutsu [Women’s Art], December 1928

Women’s Art and women artists

From the first issue of Women’s Art until H. Hasegawa’s departure for France, the magazine’s cover art featured many motifs deemed suitable for “women painters.” For example, Kuwayo Hanihara (1879–1936), who designed the first issue’s cover in July 1928, depicted tableware and fruit on a table. In the December 1928 issue, Hitoyo Kai (1902–1963) depicted Japanese and Western dolls, while F. Kametaka painted a Caucasian girl for the January 1929 issue. These images were considered appropriate for Women’s Art, as it was primarily targeted at middle-class women.

However, after H. Hasegawa moved to France, Women’s Art rapidly shifted to the left during the rise of the proletarian cultural movement in the early 1930s. This period saw the magazine introduce content on the Soviet Union and the lives of proletarian women, leading to it being banned three times. The cover art also changed, featuring photomontages of working Soviet women and geometric designs. The shift was influenced by Yuko Atsuta (1906–1983), who took over the cover art and illustrations after H. Hasegawa and was devoted to the proletarian cultural movement. Although S. Hasegawa distanced herself from such ideology, she did not waver in her original goal of providing a platform for self-expression for women of all backgrounds.

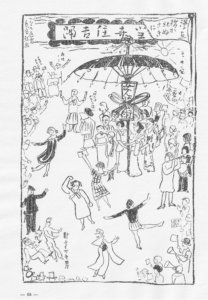

Before leaving for France, H. Hasegawa painted a striking cover image of a nude woman enjoying a seaside hot spring, a rare depiction of a nude by a woman artist. H. Hasegawa’s cartoon titled Kakarenu Saki ni – Manga [Undrawable – Manga] depicts the women of Women’s Art gathered under a large umbrella. In the lower left corner, a trembling man and another man paralysed with fear illustrate the impact of these ‘new women’. The umbrella, a symbol referencing those used in the rituals of Sumiyoshi Taisha Shrine, signifies the celebration of the future of Women’s Art. H. Hasegawa portrayed the women as free and unconstrained, a reflection of her own pioneering spirit within this community.

Haruko Hasegawa, Bath by the sea, illustration for the cover of Nyonin Geijutsu [Women’s Art], August 1928

Haruko Hasegawa, Kakarenu Saki ni – Manga [Undrawable – Manga], illustration for the cover of Nyonin Geijutsu [Women’s Art], February 1929

Shigure and Haruko after the discontinuation of Women’s Art

Due to financial difficulties, S. Hasegawa decided to discontinue Women’s Art. In response to women artists who had lost this vital platform, she launched the tabloid-style pamphlet, Kagayaku (To Shine), in April 1933, which ran for 102 issues until November 1941. However, since Kagayaku was a booklet without a cover, it offered limited opportunities for visual artists to display their work. With the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, Kagayaku became a pro-war publication. S. Hasegawa also formed the ‘Kagayaku Troop’, an organisation aimed at comforting soldiers in war zones by sending them ‘comfort bags’ containing daily necessities and essays by children.

While assisting S. Hasegawa, H. Hasegawa began reporting from the front lines in Mongolia, China, Vietnam and other countries in the early 1930s, later publishing her observations in a book. However, S. Hasegawa fell ill and died in August 1941.6 In February 1943, H. Hasegawa followed in S. Hasegawa’s footsteps by forming and chairing a wartime organisation of women painters, called the Women Artists Service Corps, which held exhibitions that sought to rally young male soldiers and collaborate to produce works expressing the nature of women’s wartime labour.7

Women’s Art magazine, founded by S. Hasegawa, provided a platform for women artists and painters to showcase their work, despite the constraints of a patriarchal society that restricted their creative freedom. As S. Hasegawa’s collaborator, H. Hasegawa played a pivotal role by inviting women painters to contribute, ensuring the magazine’s artistic recognition. Beyond their contributions to the arts, the sisters also connected women in both literary and art artistic circles to the war effort. Despite facing gender discrimination, they increasingly recognised their leadership role during the war amongst Asian women within the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Looking ahead, it is important to examine their activities and works with sensitivity, while acknowledging the intersectional nature of the discrimination they faced.

Akiko Yamazaki, “The Gender System in Art Education”, in Shinobu Ikeda and Midori Kobayashi (eds.), Visual Representation and Music, Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 2010, pp. 279-298

2

Reiko Kokatsu, “The System of Women Painters in Modern Japan: Focusing on Prewar and Postwar Western-style Painters”, Women on the Run: Women Painters Before and After World War II, 1930s-1950s exhibition catalogue, Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts (21 October–9 December 2001), Tochigi: Cogito, 2001

3

Reiko Kokatsu, “The Environment Surrounding Japanese Women Western-style Painters in the 1930s-1950s: Institutions and their Evaluations”, in All About Women Painters, edited by Natsuko Kusanagi, Tokyo: Bijutsu Nenkan Sha, 2003, pp. 30-34

4

Akiko Ogata, “The World of Women’s Art: Shigure Hasegawa and Her Milieu”, Tokyo: Domesu Shuppan, 1980

5

Akiko Ogata, “Women’s Art,” Women’s Art and Seito: The Women who Defined Their Era exhibition catalogue, Setagaya Literary Museum (10 October–24 November 1996), Tokyo: Otsuka Kogeisha, 1996

6

For more information on Haruko Hasegawa’s activities and artworks, see Reiko Kokatsu, “What Did Japanese Women Painters Draw During the War: Haruko Hasegawa and Toshiko Akamatsu (Toshi Maruki)” (pp. 25-72); Megumi Kitahara, “Wartime Artist: Haruko Hasegawa – focusing on the painting Hanoi Landscape (1939)” (pp. 73-121), in Megumi Kitahara (ed.), How Were Asian Women’s Bodies Depicted: Visual Representations and Memories of War, Tokyo: Seikyusha, 2013

7

Tomoko Kira, Women Painters and War, Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2023

Kira Tomoko is a researcher; her areas of expertise are Japanese art history and gender history. KIRA received her PhD from the Graduate School of Social Sciences and Humanities of Chiba University in 2010. She published War and Women Painters in 2013, Women Painter’s War in 2015. She won Women’s History Aoyama Nao award in 2014. KIRA wrote papers “Women Artists Service Corps and ‘Japanese Women All Working Together for the Great East Asia War Effort’” Bijutushi in 2002, “Women and Doll Making in Modern Japan: Reinterpretation of UEMURA Tsuyuko and her activities” Ningyogangu Katachi Asobi in 2018. She wrote newspaper columns “Art from a Woman’s Perspective” and “Thinking About “Flaming”” on Tokyo Shimbun in 2016 and 2021.

An article produced as part of the “Women Artists in Japan: 19th – 21st century” programme.

Tomoko Kira, "The sisters Shigure and Haruko Hasegawa, and Women’s Art magazine." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/les-soeurs-shigure-et-haruko-hasegawa-et-la-revue-nyonin-geijutsu/. Accessed 2 February 2026