Research

Anna Ancher, Solskin i den blå stue [Sunlight in the Blue Room], 1891, Skagens Kunstmuseer – Art Museums of Skagen

Since the 1960s and 1970s there has been a growing tendency to produce exhibitions featuring exclusively female artists as a feminist mode of curating, in order to address the imbalance and gender discrimination in the art world and to highlight marginalised artists who have been forgotten or left out of history.

Although this approach is a recent phenomenon that emerged with the so-called second-wave feminism of the 1970s and the emergence of curation as a critical and investigative field, there are, in fact, important examples of women’s political and feminist-oriented exhibitions much earlier. Already in 1920 the Danish Women Artists’ Retrospective Exhibition (Kvindelige Kunstneres Retrospektive Udstilling) was organised and presented by ambitious and enterprising women at The Free Exhibition (Den Frie Udstilling) organisation in Copenhagen, with the aim of highlighting and documenting the work of female artists.

Women-only exhibitions have brought critical attention and have been and still are the subject of many debates about feminist curation. These debates centre around whether it is counterproductive to view artists through the lens of gender, or whether such an approach is necessary for achieving equal visibility for female artists. Historically, however, feminist curation and the sole focus on women artists have been important tools for creating a platform where the female artists could present their art.

The Women Artists’ Retrospective Exhibition was an initiative of the Danish Women’s Artist Association (Kvindelige Kunstneres Samfund), one of the world’s oldest professional associations for women artists. It was founded in 1916, when the political landscape in Denmark had shifted – the women’s movement had gained ground and women had obtained the right to vote the year before. The time had now come for equality in the field of art as well.

It was only in the late nineteenth century that women had been given the opportunity to improve their skills and educate themselves as artists at art schools. And although several female artists around the time of the establishment of the Women’s Artist Association took an active role in the Danish art scene, participated in exhibitions, and received attention in press reviews, the local art world was still dominated by men. Women were even excluded from several established artist organisations.

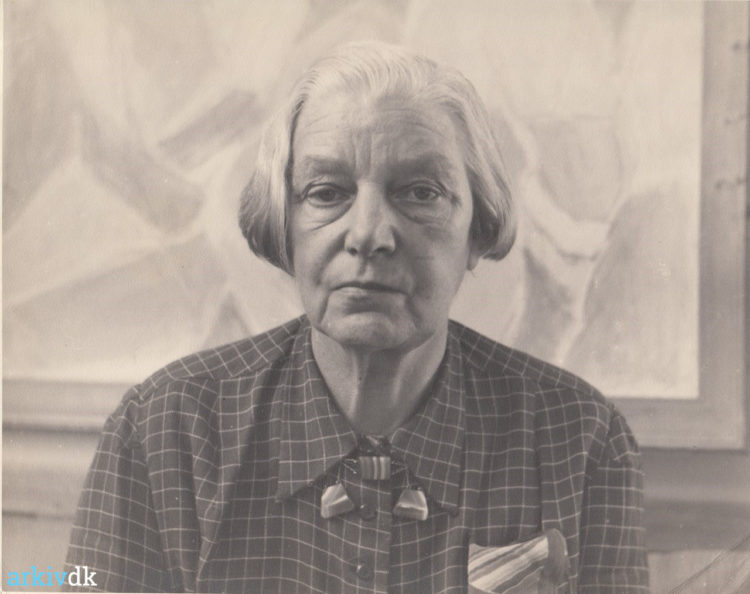

The initiators of the Women’s Artist Association were the painters Marie Henriques (1866-1944) and Helvig Kinch (1872-1956), and the sculptor Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen (1863-1945). The purpose of the association was to fight for female artists to have the same opportunities and rights as their male colleagues. More specifically, the aim was to gain more influence at the most important art educational institution of the time, the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. Women gained access to education at the academy in 1888, but they had far from achieved full equality with their male colleagues; indeed, they were kept out of the decision-making processes of the academy and thus had no political influence.1 Therefore, the ambition of the Women’s Artist Association was to campaign to have female artists represented on committees, juries and in the powerful council that headed the academy, which all primarily consisted of men. At that time, the path for entering the art scene and gaining visibility was most often through being accepted into censored exhibitions, and the association therefore wanted to gain influence and strengthen exhibition opportunities for female artists by having women represented on the significant censorship and exhibition committees.2

Although exhibition planning was not initially a direct focus of the association, nevertheless one of its first major initiatives was to arrange the exhibition, and such projects have been an important part of its mission ever since. The aim was for women artists to present their work on their own terms and to ensure visibility.

As early as it was, the exhibition was not the first in Denmark to present exclusively female artists (earlier in 1891, 1911 and 1912 a few small shows had been held, and in 1895 the large Women’s Exhibition of Past and Present (Kvindernes Udstilling fra Fortid og Nutid) was held in Copenhagen as a follow-up to the World’s Fair in Chicago 1893). But the Women Artist’s Retrospective Exhibition was the largest and most unified exhibition of Danish women’s art.

With works from 1740 until 1920, it was an attempt to cover Danish women’s art of the previous two hundred years. The ambitious and large-scale exhibition that presented as many as 199 artists with a total of 590 artworks consisting of paintings, sculptures, prints and crafts, took place from 18 September to 14 October 1920. Among the exhibiting artists, 30 deceased artists from different time periods were represented with 79 works, while 511 works were by contemporary women artists, and so the show was divided into two sections.

The exhibition was organised by chairman of the association Marie Henriques and a committee set up for the purpose, consisting of the artists Helvig Kinch, Berta Dorph (1875-1960), Marie Sandholt (1872-1942), Olga Jensen (1877-1949), Nanna Johansen (1888-1964) and Agnes Lunn (1850-1941).

Ludovica Thornam, The Artist Vilhelm Kyhn, 1868-1896, Statens Museum for Kunst – National Gallery of Denmark

The older section presented landscapes and animal paintings, portraits by the artists Elisabeth Jerichau Baumann (1819-1881) and Ludovica Thornam (1853-1896), and still-life paintings with flowers by Hermania Neergaard (1799-1875) and Julie Hamann (1842-1916), including the work Blooming Iris [Blomstrende iris] (1897), among other works.

Anna Ancher, To gamle, der plukker måger [Two Old People Plucking Gulls], 1883, The Hirschsprung Collection

The newer section presented seascapes by Louise Bonfils (1856-1933), one of Denmark’s

only female marine artists, porcelain by the potter and artist Harriet Bing (1863-1919), and modernist paintings by Ebba Carstensen (1885-1967) and Astrid Holm (1876-1937). It also included portraits by Bertha Wegmann (1846-1926) and paintings from the Modern Breakthrough movement such as Solskin i den blå stue [Sunlight in the blue room, 1891] and To gamle, der plukker måger [Two old people plucking gulls, c. 1883] by Anna Ancher (1859-1935).

The catalogue is indispensable in understanding the exhibition as feminist curating. It begins by stating that next to men, there have always been women who took part in the struggle to become professional artists,3 followed by several international examples, such as Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) and Angelika Kauffmann (1741-1807). The intention of the exhibition is not directly stated, but the introductory words and the following biographical sections about the deceased artists testify to the fact that the organisers believed that female artists had not received the adequate and deserved representation, either historically in the established art canon or while they were alive, and it demonstrates a desire to pay tribute to and create awareness about Danish women artists.

Although the historical part of the exhibition did not take up nearly as much space as the new part, it did play an important role, as the show’s title indicates. The focus on contemporary artists was natural. The section was open to both members and non-members of the association, and so a range of works were displayed.

With almost six hundred catalogue entries, the exhibition required a great deal of planning and research, and the organisers reviewed several museum collections and catalogues to gather material.4 This indicates a strong desire to create a thorough overview of women’s art through time as well as to ensure the deceased female artists a permanent place in Danish art history. Though noted in the catalogue, it is clear that it was not possible to find information about all the artists, which, ironically, highlights the need for such an exhibition.

Well received and with a solid attendance, the exhibition was generally praised by critics. One emphasised the quality of several of the works on display – by the artists Sophie Holten (1858-1930) and Edma Stage (1859-1958), among others – and expressed her astonishment at the fact that the names of the artists did not receive more attention; that they had been forgotten. Another noted that it was only on occasions like the exhibition that one realised the importance of women artists to Danish art.

The exhibition revealed that inequality in the art world was not a question of content or quality, but of lack of visibility. However, the works in the show did not sell well, and the Women’s Artist Association ended up with a small financial loss. Today many of the participating artists are more or less unknown to the wider public, but few are represented in museums and public collections, and a large part of the artworks have still not been located. Despite the great effort, there is still a long way to go to cement female artists’ place in the master narrative of art. But this exhibition was a step in the right direction. And it was a necessity at a time when female artists lacked professional communities and exhibition opportunities on an equal footing with men. Seen from today’s perspective, it can be said to be an expression of feminist curating, long before the concept was formed.

Marie Laulund, “Pionergenerationen,” in 100 års øjeblikke – Kvindelige Kunstneres Samfund, ed. Charlotte Glahn &and Nina Marie Poulsen (Copenhagen: SAXO, 2014), pp. 28-29.

2

Ellen Tange, “Kvindernes fremtidige kunsthistorie”, in ibid., p. 304.

3

Kvindelige Kunstneres Retrospektive Udstilling (exh. cat. Copenhagen: København, 1920).

4

Tange, “Kvindernes fremtidige kunsthistorie”, p. 304.

Sofie Normann Christensen is an art historian. She has worked as Curatorial Assistant at Ordrupgaard, Copenhagen, and Kunstforeningen GL STRAND, Copenhagen, and as a Curator and Project Coordinator at Museum Jorn, Silkeborg, Denmark.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.