Research

Jean LaMarr, Some Kind of Buckaroo, 1990, screen-print, 26 x 38 in / 66.04 x 96.52 cm, Collection of the Nevada Museum of Art © Jean LaMarr

This article gives a brief overview of Native American women’s contributions to the formal art world in the latter half of the 20th century. During this period, Indigenous artists blended modernist and traditional Native art forms and asserted that their work was worthy of being exhibited in the world’s finest art institutions. This proliferation of Native American art did not exist in a vacuum but was deeply shaped by the Red Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s which fostered a rebirth of Native politicisation, pride and cultural revitalisation. Native American artists reflected this political consciousness through their art and through the formation of art organisations such as The Grey Canyon Group or art institutions like the Gorman Museum of Native American Art at the University of California, Davis.

It is imperative to acknowledge that Native American women have been crafting experimental and innovative art since time immemorial. In fact, most Native art has been and continues to be made by women. Renowned art institutions have rarely acknowledged this fact. Instead, the art produced by Native American women has been diminished. They have been regarded as outside the canon and their innovations have not been recognised. The fact that these artists are both women and Native American results in a double marginalisation that has often led to their works being sold as souvenirs or used only for ethnographic study. Until relatively recently, both Native American men and women artists were resigned to showing their works in trading posts rather than formal art galleries or museums.1

In the 1960s and 1970s, the tide began to turn with the burgeoning of Red Power, which was an inter-tribal political movement committed to the recognition of Indigenous sovereignty, Native self-determination, the protection of Indigenous human rights and the restoration of treaty territories and lifeways.2 The movement was both urban and rural, but first burst on the scene in California’s Bay Area in a newly concentrated community of urban Native Americans. Thousands of Native Americans, in search of economic and educational opportunities, took part in the federal government’s Relocation Program which moved Native Americans from reservations to assimilate them into American cities and towns. Like other marginalised communities, many Native Americans faced poverty, limited social mobility, racism and police brutality. Red Power became a fiercely anti-colonial political movement that manifested in a variety of ways. Most famously, groups such as Indians of All Tribes and the American Indian Movement launched occupations of Alcatraz Island, the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in the nation’s capital and the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. For perhaps the first time in the 20th century, Native Americans and their critiques of the settler colonial state were impossible to ignore. The end results included the creation of Indigenous studies programmes at universities, the legal freedom to practice Indigenous religions and ceremonies and the creation of tribal colleges and museums. Another undeniable result was the revitalisation of Native American cultures, which manifested through the ways people chose to dress, how they chose to live their lives and raise their children and in the art they created.

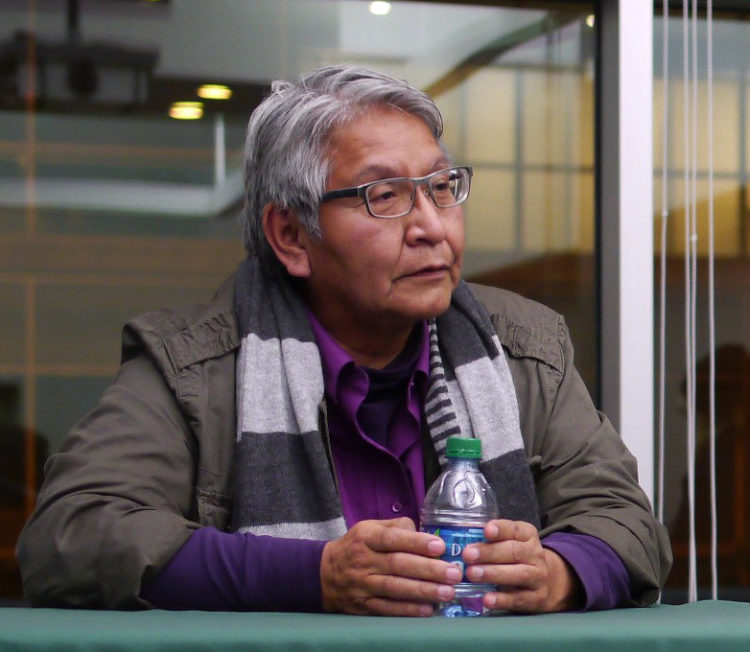

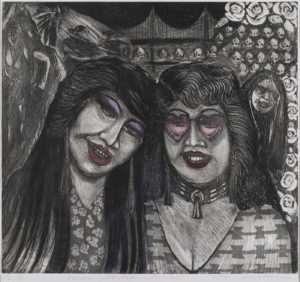

Jean LaMarr, Urban Indian Girls, 1982, etching, 55.88 x 60.96 cm / 22 x 24 in, Nevada Museum of Art, Reno © Jean LaMarr

In the shadow of this political excitement, a growing number of formally trained Native American artists, many of them women, began their careers. Some women, such as Northern Piute/Pit River artist Jean LaMarr (1945) directly used their art to further the Red Power cause. J. LaMarr, on relocation in Berkeley, learned the art of mural making from Chicano/a activists. She then created murals, posters and flyers for Red Power’s various organisations, events and occupations.3 Her political consciousness has been a touchstone in her career, and she currently teaches art to young Native Americans in her community of Susanville, California. J. LaMarr, and many other Native American women artists of the era, also explored the experiences of urban Native American life in their artwork. J. LaMarr’s etching Urban Indian Girls (1982) portrays smiling Native women, wearing hints of their traditional regalia as a sign of cultural pride, with the Golden Gate Bridge as a backdrop. This work, and others like it, reflect on the shifting social worlds for Native Americans in the latter half of the 20th century.

Kay WalkingStick, Chief Joseph Series (detail), 1975–1977, acrylic and wax on canvas, 50.8 x 38.1 cm / 20 x 15 in each, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington © Kay WalkingStick

Kay WalkingStick, Orilla Verde at the Rio Grande, 2012, oil on wood panel, 101.6 x 203.2 cm / 40 x 80 in, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington © Kay WalkingStick

Cherokee painter Kay WalkingStick (1935), an MFA graduate of Pratt Institute, also began her artistic career in the early 1970s and primarily focused on pop art-inspired, silhouetted depictions of the body. After exposure to the Second Wave Feminist and Red Power Movements, she began to explore her Native identity through her paintings.4 One of the first works in which she did this was her Chief Joseph (1974-1977) series which meditates on Native historical pain, resistance and memory. Throughout the rest of her career, Indigenous themes have continued to appear, most notably with her painted American landscapes which feature inlays of traditional Native designs. These pieces are assertions of Native political and cultural sovereignty over the land and ask onlookers to reconsider their relationships to these natural spaces.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Celebrate 40,000 Years of American Art, 1995, collagraph, 1.94 x 1.34 m / 76.5 x 53 in, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Gifts For Trading Land With White People, 1992, oil and mixed media, 4.32 x 1.52 m /14.2 ft x 60 in, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Emmi Whitehorse, Fire Weed, 1998, chalk, graphite, pastel and oil on paper mounted on canvas, 38 1/2 x 50 in / 97.8 x 127 cm, Brooklyn Museum, New York, gift of Hinrich Peiper and Dorothee Peiper-Riegraf in honor of Emmi Whitehorse © Emmi Whitehorse’s estate

Others, like the acclaimed Salish and Kootenai artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940), began organising Native artist associations to create both community and bargaining power. As a graduate student at the University of New Mexico in the 1970s, J. Smith founded the Grey Canyon Group for Native American contemporary artists. The group, which referenced the concrete “canyons” of cities, included the likes of Navajo artist Emmi Whitehorse (1957) and Felice Lucero-Giaccardo (1946) of San Felipe Pueblo. Together they faced the challenges of meeting the Euro-centric expectations of art school and efforts to get their work noticed by galleries and institutions. It was a real dilemma. Both J. Smith and E. Whitehorse were told by their professors that their work was “too Indian in appearance”.5 To pass classes, the two women conformed to European modern abstraction to “make their marks”.6 And when they went to find exhibition venues for their Grey Canyon Group, they were told their work was not “Indian enough”.7 J. Smith recounted in a recent interview, “This commentary was a disavowal of who we were as a people. It meant that others had the power to decide the merit or value of our artwork based on racial stereotyping”.8 Nevertheless, the Grey Canyon Group managed to exhibit their work locally, nationally and internationally. J. Smith has dedicated her career to pushing the boundaries of Native American art through her own artistic and curatorial endeavours. Some of her most politically charged work includes Gifts for Trading Land with White People (1992), Tribal Map (2000) and Celebrate 40,000 Years of American Art (1995). Her dedication to greater representation of Native American women in the art world is best exemplified in her co-curated show with Harmony Hammond (1944), Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar, and Sage (1985) which featured over thirty contemporary Native American women artists.9

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, Vanna Brown, Azteca Style, 1990, collage of gelatin silver prints, 38.4 x 57 cm / 15 1/8 x 22 7/16 in, Museum of Modern Art, New York © 2022 Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie

Others, like Seminole-Muscogee-Navajo artist Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie (1954), also experimented with photography to express themselves. She began her career in the late 1970s and has since utilised both original photographs and retooled historical photographs of Indigenous peoples. Her photographs are meant for the Native American gaze and serve as a tool of historic and contemporary reclamation. She was first inspired to take up photography after seeing the work of the South African photographer, Ernest Cole (1940–1990), which prompted her to make connections between international manifestations of settler colonialism. Her most well-known works include Vanna Brown, Azteca Style (1990) and her mesmerising series Portraits Against Amnesia (2003). Since 2004, she has served as the director of the Gorman Museum of Native American Art.

Countless other Native American women artists of this generation contributed innovative art. Some of those trailblazers include the Wasco-Yakama artist Lillian Pitt (1944), Mi’kmaq and Onondaga writer and artist Gail Tremblay (1945–2023) and Hopi and Choctaw artist Linda Lomahaftewa (1947). These women used a multitude of mediums from sculpture to mixed media to assert their artistic ability, cultural sovereignty and their own meditations on identity. Together these women pursued formal educations in the arts, blended European and Indigenous artistic canons, and laboured to make the art world pay proper attention to their craft. Generations of Native American women artists have followed in their footsteps. From the intricate beadwork of Kiowa artist Teri Greeves (1970) that depict contemporary Native life to the historically poignant pictures of Apsáalooke photographer Wendy Red Star (1981). These artists’ efforts led to ground-breaking exhibitions like Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists which showcased the brilliance of Native women artists over more than two millennia.

Of course, this greater acceptance of Native American art in formal art institutions is also the result of the radical, political and social changes that gave rise to the creation of new or reformed museums and galleries. For example, the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C. did not open its doors until 2004. Artists, curators, gallerists and museum directors have all contributed to the efforts to better represent the ingenious art created by Native American women. Nevertheless, Native American women artists continue to be marginalised when compared to the likes of cis, white and heterosexual male artists of the 21st century. The creation of shows such as Hearts of Our People or recent major retrospectives on K. WalkingStick, J. LaMarr and J. Quick-to-See Smith have begun the work of properly showcasing and celebrating the contributions that Native American women have and continue to make to the art world.10

Jill Ahlberg Yohe and Teri Greeves, Hearts of Our People: Native American Women Artists (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2019), 12–15.

2

Kent Blansett, A Journey to Freedom: Richard Oaks, Alcatraz, and the Red Power Movement (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 4.

3

Ann M. Wolfe, The Art of Jean LaMarr (Reno: Nevada Museum of Art, 2020), 12–14.

4

Smithsonian NMAI, “Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist,” YouTube, 25 November 2015, educational video, 1:50 to 3:36, https://youtu.be/_TOI7kAh3pg.

5

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, “Jaune Quick-to-See Smith – Salish and Kootenai,” interview by Shilo George, Contemporary North American Indigenous Artists, 9 June 2011, https://contemporarynativeartists.tumblr.com/post/6346633044/jaune-quick-to-see-smith-salishkootenai.

6

Ibid.

7

Ibid.

8

Ibid.

9

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Women of Sweetgrass, Cedar, and Sage: Contemporary Art by Native American Women (New York: American Indian Community House, 1985).

10

Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists, (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 2 June–18 August 2019); Kay WalkingStick, Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist, (Washington D.C.: National Museum of the American Indian, 7 November 2015–18 September 2016); Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 19 April –13 August 2023).

Raven Manygoats is a Diné and Bilagáana History PhD student at Rutgers University. Her research focuses on Native American women’s activism in the era of Red Power. Her work examines both radical and grassroots efforts made by Native American women to ensure both land and bodily sovereignty in the late 20th century. In her work, she draws on Indigenous feminist theory, Native cosmologies, oral tradition and materials produced by organisations like the American Indian Movement (AIM). Additionally, she serves as a graduate assistant for the Art of the Americas at Rutgers’ Zimmerli Art Museum.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Raven Manygoats, "Native American Women Artists in the Late Twentieth Century." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/les-artistes-femmes-autochtones-des-etats-unis-dans-la-seconde-moitie-du-xxe-siecle/. Accessed 4 July 2025