Research

“A propósito de identidades : todo sobre mi madre”, article written by the Mexican artist Magali Lara for the publication marking MUMA’s 7th anniversary, MUMA. Museo Mujeres Arte Goce Encuentro, ed. MUMA, 2015.

Focus on MUMA : Museo de Mujeres Artistas mexicanas

Magali Lara, Ana Quiróz, Lucero González, Angélica Abeyllera, members of MUMA, 2015, © MUMA, Lucero González

MUMA: A new kind of museum of women artists

Drawing on a long-time multidisciplinary bond and friendship, the representatives of MUMA, Museum of Mexican women artists – through its founder, the visual artist and photographer Lucero González – embody a gathering of novel initiatives in favour of the representation of female figures in the history of art. Prompted by the heritage of activism and gender studies, this virtual museum testifies to the proactive approaches of Latin-American personalities in the art world, working towards the acknowledgement and promotion of female artwork in the 20th and 21st centuries.

MUMA, Museo de Mujeres Artistas mexicanas was created in 2008 at the instigation of Lucero González, a committed feminist activist, thanks to an award she received from the Sociedad Mexicana Pro Derechos de la Mujer A.C. Semillas.1 This virtual museum offers to “dis-cover” – by taking away the veil that concealed them for so long – a gallery of artists’ portraits, a complete range of visual expressions that pays tribute to the great artists active throughout the last two centuries. MUMA’s interactive platform functions as a critical and scientific interface, rather than a simple display of artwork. It includes innovative reflections and aesthetic museum strategies that combine the will to bring visibility to the heritage of women’s art and the necessity to integrate the accessibility provided by social networks to maximise their promotion across the border and abroad. Far from offering only “dematerialised” contents, the museum has developed strategies to valorise their contents by constituting an online database of archives and discussion documents on the productions of México’s women artists.

“Nowadays,” says Lucero González, “a growing number of women graduate from art schools all over the country and yes, we can now confirm that at least 50% of these students are women. There is a considerable production of artwork in the fields of photography, video, painting, performance art, installation, art-action, street art, and public art… Faced with this blatant absence and this lack of archives accounting for the work created by Mexican women artists, I seized the opportunity and necessity to build this missing heritage.”2

MUMA offers a resolutely new understanding of museography in that it creates a semantic link between the artists and their works, thanks to an interactive gallery that presents artists in alphabetical order (“artistas” section), as well as critical and aesthetic documentation that provides exhibition texts specially written for the website. The museum’s consultative steering committee (made up of reputed historians, art critics, artists, and curators),[meets once a year to organise three annual exhibitions. There can be two types of exhibitions: virtual exhibitions essentially created by and for the MUMA website, or itinerant exhibitions shown at temporary venues, such as the University of Guanajuato in 2012 or the Museum of Modern art in México D.F. in 2015.

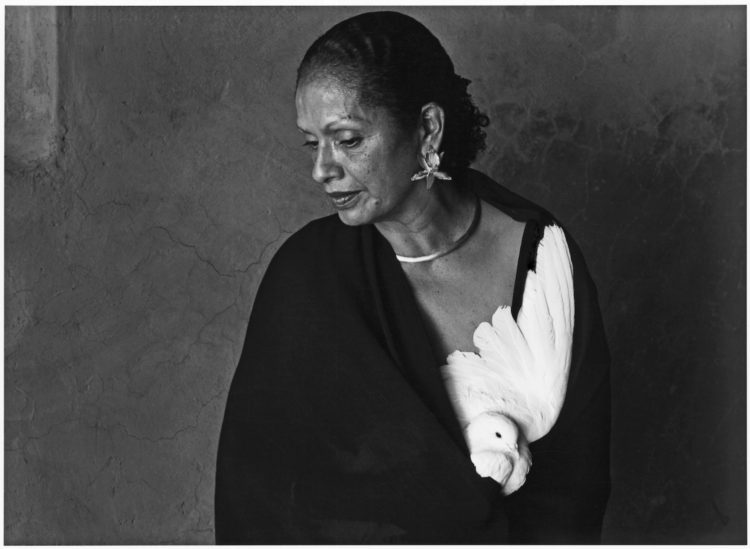

Lucero González, Mi hija, yo misma, photograph, 1980.

Lucero González, Mi hija, yo misma, photograph, 1994.

Minerva Ayón, Infectados II, 2009, textile, 150 x 150 x 100 cm, © Minerva Ayón.

Thinking in the “present”: the discursive genealogies of several generations of visual artists

Studying the museographic spaces dedicated to women artists in Mexico calls to attention the blatant lack of diversity in major cultural institutions, whether Latin-American or around the world. Virtual museums and other archive platforms focusing on women’s art reveal the institutional gulf and how deliberately ill-aware they are of the principle of equal representation of men and women in their programmes. In this respect, MUMA defends the promotion of archives on women artists, discussional and approached in relation to present times through problematized exhibitions. The compilation of older works stands alongside those of a new generation of artists, often still students or recent graduates. This artistic lineage is the focus of the virtual exhibition based on the article “A propósito de identidades: todo sobre mi madre”, written by Magali Lara (b. 1956 in México) for MUMA’s 7th anniversary. Drawing inspiration from the concept of the “maternal continent” developed by Julia Kristeva, Magali Lara’s corpus readily associates Louise Bourgeois with the work of Minerva Ayón (b. 1985), a young artist who channels her own mother’s illness through the creation of very large textile pieces.

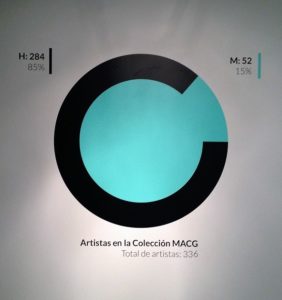

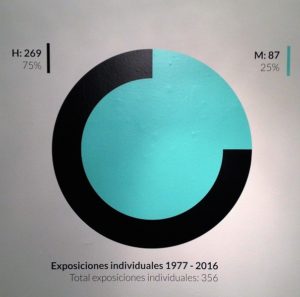

The diagrams were shown during the exhibition Ejercicios exploratorios II. Creadoras contemporáneas en la colección MACG, from 3 June to 13 November 2016. © Museo Carrillo Gil, 2016.

Diagrams revealing the estimated percentage of monographic exhibitions in terms of gender ratio at the Carrillo Gil Museum (Mexico D.F.) between 1977 and 2016, as well as the breakdown of artists by gender.

The under-representation of women artists in Mexican cultural institutions

But the initiative of creating MUMA also reflects a deep questioning of the reason for the existence of such a museum these days. For decades, as shown by Cynthia Silvana Gesualdo6 – a researcher specialised in museums and the issue of the institutional visibility of Mexican women artists –, Mexican cultural institutions have consistently ignored the fundamental principle defended by the 2009 Torréon Declaration, which pointed out, via the INTERCOM (International Committee on Management), the responsibility of museums in the promotion of marginalised groups, encouraging them to respect equality between individuals regardless of beliefs or origins. As early as 2011, Gesualdo’s study compared the men/women ratio in the country’s major official cultural institutions, such as the Museo Nacional de San Carlos (MNSC), the Museum of Fine Arts of Mexico, also known as Museo Palacio de Bellas Artes (MPBA), and the Museo Nacional de Arte (MUNAL), out of a total of 244 temporary exhibitions held between 1995 and 2011.

In addition to the predictable results in terms of disparity in monographic exhibitions and extremely low participation of women during the collective exhibitions organised by these three institutions, Gesualdo also noticed a clear decline in the number of monographic propositions over the past 20 years. For example, MUNAL (Museo Nacional de Arte) has held no solo exhibition for a woman artist since 1992, against 22 dedicated to male artists. The results of the Museo Nacional de San Carlos, which was founded in 1968, are even more alarming: in 44 years of existence, there have been no monographic exhibitions of women artists, against 21 dedicated to men. The Museo Palacio de Bellas Artes (MPBA) counts 10 monographic exhibitions of women artists against 60 for male artists. More recently still, the artist Mónica Mayer simply exposed the sad conclusion shown in the form of diagrams on the walls of the Carrillo Gil Museum during the exhibition Ejercicios exploratorios II. Creadoras contemporáneas en la colección MACG7 : only 15% of the 336 artists in the Carrillo Gil collection are women, among whom only 25% were granted a monographic exhibition between 1977 and 2016.

Continuity and performativity of the archive

A feminist archive presented “in the future”

The major issue here, in turns materialised and dematerialised by the archive interface, consists in evading the order established by the official history of art, instead nesting in performative interstices and showing, over and over, celebrated or regrettably little known works, in order to revivify a bedrock of knowledge about feminist art in general, and Mexican feminist art in the specific case of MUMA. Other reiterative initiatives and conservation measures have been launched this past decade, prompted by the vast innovative potential provided by the Internet in the 2000s: Re.act.feminism#28, an itinerant exhibition inaugurated at the Montehermoso Kulturunea cultural centre in Vitoria-Gasteiz (Spain), which gave the public the opportunity of watching on request over 70 video documents on feminist performances from all over the world; and more recently the Australian platform Future Feminist Archive9. Each of these initiatives is the result of a will to improve contributive platforms and the promotion of the works of contemporary women artists by giving the archive performative and dialectic value.

Mónica Mayer, Presentation of El Tendedero in Medellín in May 2015, on the occasion of the Medellín International Art Fair (Colombia) held at the Museo de Antioquia (October 2015 – February 2016), next to a mural photograph of its first presentation at the Museum of Modern Art in México, in 1978, © Mónica Mayer, Pinto mi raya.

Mónica Mayer, documentation of her many previous presentations of El Tendedero (Museum of Modern Art México in 1978, California in 1979, during the Wack! exhibition in Los Angeles in 2007) in Medellín in May 2015, during the Medellín International Art Fair (Colombia) held at the Museo de Antioquia (October 2015 – February 2016), © Mónica Mayer, Pinto mi raya.

Mónica Mayer, presentation of the documentation of the actions linked to El Tendedero in Medellín, during the Medellín exhibition (Colombia) held at the Museo de Antioquia (October 2015 – February 2016), table inviting the active participation of the public in the assemblage of the Medellín Tendedero.

Virtual vs. “in situ”: a focal point of curating

An important issue today is the ethical problematisation of the contributions and challenges of the virtual field in order to crystallise the exchange and contribution networks around women’s art. In October 2010, the symposium “Women: Museum. Between Collection Strategy and Social Platform”13 organised by Elke Krasny at the Vienna City Library, tried to raise issues inherent to the dichotomy between museum strategies and social platforms. The symposium was held only a few months after MoMA’s own, “Art Institutions and Feminist Politics Now”, and established connections between the specificity of contemporary artistic practices, the place of women artists in institutions, and the role of feminist heritage in curatorial practices.

From a broader point of view, what gives the virtual feminist museum its maximal expression of societal commitment is the “event-encounter”, a concept developed by the feminist theorist Griselda Pollock14 :

“The virtuality (…) concerns the creation of a different kind of archive that can deepen the understanding of art practices, not for their representational function, but as sites of creative difference, as poetic events, ever waiting to be read in the spaces they open up once we weave new webs of connection and conversation and thereby allow new encounters.”15

Karen Cordero, Graciela de la Torre, Mónica Mayer, © Lucero González

Lorena Wolffer, wall of Evidencias, in Expuestas: registros públicos, Museo de Arte Moderno; curator: Octavio Avendaño; 11 July–18 October 2015, México D.F., © Lucero González.

A plural art: revisiting the militant multidisciplinary approach

The archival palimpsest as a method, (a) memory(-ies) of the collective: the operational modes and circularity of discourses on art

MUMA also involves an interlocking of curatorial projects that demonstrate a practice of the artistic and critical palimpsest. Karen Cordero16 and Mónica Mayer strive to combine these research issues in their respective disciplines, but with a collective, not to say “retro-collective”17, ambition. Another MUMA protagonist, the performer Lorena Wolffer, questions gendered social relationships through the subject of violence against women.18 In Evidencias (Evidence), a virtual exhibition at MUMA, Lorena Wolffer collected everyday objects used to commit various acts of violence against women – “stigmatic” objects, pieces of evidence given by victims of violence or by their relatives when they were no longer there to testify. In 2015, the exhibition Expuestas: registros públicos, organised at the Museum of Modern Art in México, included a wall of objects collected during its previous presentation of Evidencias, juxtaposing the “evidence” given by female victims of violence and showing it to the general public.

In this respect, through the artist’s approach and the first presentation of Evidencias, MUMA proposes a first reflection phase, while also challenging the presumed “bell jar” traditionally associated with the exhibition space – a linear system that presents a faultless discourse, just as the work of art is perceived as a “finished product”. Thus the virtual exhibition becomes a medium, a means rather than an “end” per se. The tribute and reiterative activation process took a new turn when Lorena Wolffer presented the exhibition Documentary altercations. Revision of performances by women artists at MUMA, in which she associated Mexican feminist action-art pieces with scalable and critical resources. Based on the inescapable conclusion that any performance document inevitably alters the original action, Wolffer encouraged five Mexican women artists to interpret the documents and archives about their own work:

“The five reinterpretations came in a variety of experiences: while Mónica Mayer’s intervention proposed a collection of photographs of her work El Tendedero, Katia Tirado’s participation included documentation about three older works. I firmly believe that it is we, women artists, who should record and archive our works to save them from oblivion or their probable eviction by hegemonic narratives; but what truly stimulates me is the idea that we can reinterpret these works ourselves several years after creating them. I believe that these interpretations reveal singular aspects concerning the shifting of artwork in time and space, involving mutations and meaning, while also articulating new and unsuspected works of art.”19

By constantly renewing the visions and conditions for the critical reception of the works of art they promote virtually, the members of MUMA allow for an exchange of visions conceived through others, by others, collectively. The reflexive inventiveness on which this exchange relies depends on bold scriptovisual curatorial propositions. Starting with the singular, we soon find ourselves deep within an infinite discursive History, where memory is summoned as a duty and challenged as a necessity20. Therefore, it is hard to consider MUMA without articulating the multiplicity of singular careers of each of its members. Of course, these reflections must also be applied to the no less important works and approaches of its other members, which, although only mentioned by name, also form the cornerstone of this gathering of intellectual Mexican women.

This article was made possible thanks to the generosity and assistance of the Association Camille, via the attribution of the Michelle Coquillat Grant in 2012.

Milena Páez-Barbat is a PhD student at Paris 8 University and assistant curator for heritage preservation. Her research focuses mainly on the links between methods of artistic production, the states of the artwork that they involve, and their possible reactivations or posthumous remakes. She is also in charge of scientific observation and forecasting on the project “Replay, restitution, recréation” carried out by Labex Arts-H2H. After collaborating in the satellite editorial platform for the exhibition elles@centrepompidou with Camille Morineau at the Centre Pompidou, she was awarded an international study grant by the Fondation Camille (Michelle Coquillat Grant) in 2012, which enabled her to travel to Mexico and Argentina to study the local network of women’s museums. She is currently the assistant of the head of collections at the CAPC-Musée d’art contemporain de Bordeaux.

Semillas is a non-profit organisation that aims to improve the condition of women and draw attention to the existence of women’s groups in Mexico (labourers, natives, employees) who face glaring social inequality and a lack of acknowledgement from society.

2

Lucero González, interviewed by Milena Páez-Barbat, Study report supported by the 2012 Michelle Coquillat Grant, in Musées de la femme en Amérique latine: les enjeux argentin et mexicain, 120 pp. Grant named after the founder of the Association Camille, in charge of the Culture department for Yvette Roudy, Minister of Women’s Rights from 1981; 180 min. interview held at the Gandhi bookshop, colonia Coyoacan, México D.F., May 2012.

3

MUMA, Museo de Mujeres Artistas Mexicanas is composed of a permanent consultative scientific committee of 11 women: 7 artists, Lucera González (photographer, video and artist), Ana Quiróz (new media artist), Grace Quintanilla (video artist), Lorena Wolffer (performance artist), Magali Lara (visual artist), Mónica Mayer (performance artist), Marta Palau (visual artist); 1 specialised journalist, Angélica Abeyllera; 2 art historians and curators, Karen Cordero Reiman (historian, curator) and Pilar García (historian, curator); 1 art critic and researcher, Sylvia Navarrete.

4

After graduating from the San Carlos Academy in the 1970s, Magali Lara began making use of the ambiguous but tenuous areas that span not only the practices of writing and drawing, but also of textile art, thus breaking with the pictorial sacralisation that prevailed at the time. She then took part in the Março group, for which the relationship between text and image was a constant source of experimentation. The Março group was an art collective founded in 1979, composed of the artists Alejandro Olmedio, Gilda Castillo, Magali Lara, Manuel Marín, and Mauricio Guerrero y Sebastián. Active from 1979 to 1982, it focused on the exploration of language and its polysemous richness by taking over public spaces on the occasion of participative performances, during which passers-by were invited to form a “collective poem” by making use of the pavement or any other element of street furniture. “The Março and No-Grupo collectives were very formative experiences, and good ways to learn the cultural codes of México. The experimental frenzy and political posture at the time greatly influenced my work and guided my later output. My memory of it remains resolutely critical – although never lacking humour –, while also taking into consideration the importance of the collective, which forges a practice enhanced by collaboration and teamwork. I would never have been able to join MUMA without these experiences.”, in Interview with the artist, by Milena Páez-Barbat, May 2016.

5

Julia Kristeva, Seule une femme, chap. “Quelle avant-garde aujourd’hui?”, Éditions de l’Aube, 2013.

6

Cynthia Silvana Liceaga Gesualdo, ¿Dónde están las mujeres artistas en los espacios museísticos mexicanos?, El fenómeno de la invisibilidad femenina en las exposiciones temporales en los museos nacionales de arte, master’s degree in museum studies and curatorship, under the dir. of Patricia Galeana Herrera, Centro de cultura Casa Lamm, México D.F, 2011

7

Ejercicios exploratorios II. Creadoras contemporáneas en la colección MACG, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, México, 2016.

8

Re.act.feminism#2 – a performing archive, itinerant project created between 2011 and 2013 by the curators Bettina Knaup and Béatrice Ellen Stammer, which inventoried almost 180 artists from the 1960s to the 1980s in Eastern and Western Europe, USA, Latin America, and the Middle East.

9

The programme of the Future Feminist Archive was conceived as an annual cycle of exhibitions, events, and symposiums under the scientific supervision of the Australian SCA Contemporary Art and Feminism cluster, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of International Women’s Day 2015. Read online.

10

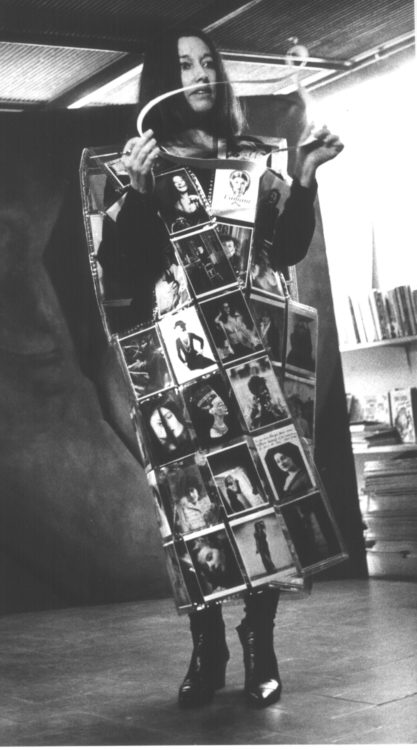

Mónica Mayer uses a simple installation (a drying rack – a semiotic symbol associated with female domestic confinement) to hang small papers on which she reproduced the answers to the following question that she spontaneously asked women in public spaces: “As a woman, what I hate the most in the city is…”. The piece is an invitation bordering on a sociological survey, which reflects the conditions of women from various social backgrounds, ages, and occupations. The work, which was presented again as a flower of feminist art during the exhibition Wack!: Art and the Feminist Revolution (Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 2007), will soon turn 40. Initially created for the Salon 77 – 78: Nuevas Tendencias in 1978 at the Museum of Modern Art of México, El Tendedero materialises a receptacle of Mexican society in the late 1970s. Presented in Los Angeles a year later, in 1979, at the invitation of the artist Suzanne Lacy for the Making it safe project, the work was adapted to its new exhibition context and focused on the insecurity felt by women at Ocean Park.

11

Expression used by Mónica Mayer to anticipate the risks of a work of art being institutionally fetishized; cf. the retrospective and trajectory of the work El Tendedero, accessible online at pintomiraya.com. Last visited on 23 August 2016.

12

Photographic reproduction system reprised in 2010 for the exhibition Máquina visual: una revisión de las exposiciones del MAM desde su colección. 1964 – 1988 at the Museum of Modern Art of México.

13

The symposium involved eminent personalities from the art world and feminist activism, such as Gudrun Ankele (Gudrun Ankele, Absolute Feminismus, Freiburg, orange-presse, 2010) and VALIE EXPORT. One of the main topics was the emergence of women’s museums on an international scale and the symbolisation of museum spaces.

14

Karen Cordero, a Mexican theoretician, feminist academic and member of MUMA, proclaims this conceptual legacy and salutes the arguments Griselda Pollock puts forward in Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space, and the Archive, London, Routledge, 2007. According to her, the “virtual museum” is an unparalleled dialectic tool, which reminds us that “the configuration of an exhibition also pertains to a form of writing”, in interview with Karen Cordero, by Milena Páez-Barbat, May 2016.

15

Griselda Pollock, “Virtuality, aesthetics, sexual difference and the exhibition: Towards the Virtual Feminist Museum », elles@centrepompidou. Women artists in the collection of the musée national d’art moderne, Centre de création industriel, exhibition catalogue, Centre Pompidou, 2009, p. 323-324.

16

The monographic retrospective exhibition of Mónica Mayer’s work at MUAC in 2016 (Mónica Mayer. Si tiene dudas… pregunte: une exposición retrocolectiva, México D.F.) aimed at highlighting the “collective and participative dynamics” inherent to the artist’s work by “inviting the public to become co-creators and accomplices in the presentation of the works exhibited. Some of the works by other artists reactivate Mayer’s works – such as Lo normal and La fiesta de quince años de Tlacuilas y retrateras – through an interpretative differential. We wished to allude to this in the exhibition, despite noticing that people were for the most part extremely attached to the perpetuation of the singular authority of the artist in the exhibition space, distinctly ruling out the perception of other factors.” Interview with Karen Cordero, by Milena Páez-Barbat, May 2016.

17

The term “retro-collective exhibition” was conceptualised by the Argentinian art historian Maria Laura Rosa on the occasion of the first retrospective exhibition of Mónica Mayer’s work from 6 February to 31 July 2016 at MUAC, University Museum of Contemporary Art in México D.F. (curated by Karen Cordero). It showcased the eminently collegial dimension of second-wave feminist groups in North and South America, and of the artist collectives that appeared in the early 70s in Mexico, which were more concerned about collective social struggle than the egocentric consolidation of the individualised and mythicized figure of the artist. In Mónica Mayer. Si tiene dudas… pregunte: una exposición retrocolectiva, México D.F., MUAC, 2016.

18

Virtual exhibitions such as Géneros fluidos – inspired by Judith Butler’s theoretical input, which initiated “queer” theory – question artistic practices that go beyond the strict binary imposed by the institution of “male” and “female” genders, and reject the idea of a naturalisation and normalisation of examples of violence against women. However, this dialectic goes further, and the artist aims at “summoning” the public and the voices of women, whether witnesses or victims, by means of “open summons”, thus making participative and social resources an inherent part of the organisation of her exhibitions.

19

Interview with Lorena Wolffer, by Milena Páez-Barbat, May 2016.

20

In autumn 2016, in response to the importance of preservation and the role of archival science and its social significance in this respect, MUMA and the Museum of Women of Mexico collaborated on a first edition paying tribute to the feminist archive (“Reconocimiento al Archivo Feminista”), published on 3 September 2016 and focusing on the iconic figure of Ana Victoria Jiménez. This is the first time such an anniversary is celebrated, yet again revealing the energy and daily commitment of these very active members of MUMA, who fight unrelentingly for the visibility of Mexican women artists to be finally acknowledged and shared.

Milena Páez-Barbat, "Present, continuous, past(s) – A virtual museum at the service of the (re)cognition of women artists in the 20th and 21st centuries." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/present-continuous-pasts-a-virtual-museum-at-the-service-of-the-recognition-of-women-artists-in-the-20th-and-21st-centuries/. Accessed 8 July 2025