Interviews

A feminist artist working in performance, video, drawing, painting and installation since 1970, Nancy Buchanan (b. 1946) has been an underground hero of the Los Angeles art and performance scenes for many decades.

She grew up in the Los Angeles area, and briefly in Palo Alto, and has worked in California for decades, aside from a brief stint teaching at the University of Wisconsin, Madison in the early 1980s. Receiving both her Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts degrees from the Department of Art at University of California, Irvine (UCI), N. Buchanan was one of the members of the infamous first graduating MFA class, which also included Chris Burden, who performed his notorious Five Day Locker Piece as a student (more on this below) and fellow feminist performance art pioneer Barbara T. Smith, and was guided by LA art world luminaries, including Robert Irwin, and Larry Bell, who were teaching there at the time.

N. Buchanan went on to become an admired visual and performance artist, video/filmmaker, writer/editor, and teacher, spending twenty-five years at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). She was a co-founder of the Double X collective, and is still active in bridging generational discussions about feminist art and women artists.

This conversation is drawn from two different interviews framed by the coronavirus pandemic and its restrictions – one via Zoom on 28 July 2020 and one in person on 5 May 2021. I approached the conversations through the framework of a crucial aspect of N. Buchanan’s practice as a feminist artist – one which, as with so many powerful feminist mentors, has largely been ignored by the larger art and institutional worlds – that is her role in supporting and helping to expand the Los Angeles art scene beyond the white artists emerging from the art schools in the 1960s and 1970s. As Black artist Senga Nengudi, who was active in Los Angeles in the 1970s, put it to me in an interview, while the feminist art institutions in Los Angeles that were appearing at this time (such as the Woman’s Building) tended to exclude Black and Latinx women artists, “all praise must go to Nancy Buchanan”, who was an exception: “She is truly for real.”1

It is N. Buchanan’s largely unacknowledged emotional and logistical labour in supporting and promoting work by Black and Latinx and other younger artists across the spectrum of gender/sex, ethnic and class identifications that provides the focus of this dialogue. This kind of work is too often neglected or ignored, but is integral to forming the basis for any structural change in the patriarchal and white-dominant institutions that continue to restrict art exhibition and curating.

AGJ: What inspired you to start engaging the art world in this activist way, not only persistently making work with feminist themes and using feminist strategies (from body art to quilting) but approaching your life as an artist by acting out of concern for others?

NB: Besides the collaborative nature of the UCI graduate group, it was fortunate that I was a member of Double X [also spelled XX] … which grew out of the cooperative gallery at the Woman’s Building in the 1970s, after it moved from the location at the old CalArts site to downtown Los Angeles.2

Connie Jenkins, was part of the Double X project and was a real force; one of the projects that Double X decided to do was to host a screening of films by women of colour at Barnsdall [Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery] and I was the point person to organise that.3 That’s how I met Barbara McCullough,4 who curated the film evening and remains a very good friend of mine … So many people turned out to see those films that we had to ask the projectionist to stay to do another screening. …

That was 1979 … I did a small retrospective of Double X a couple of years ago at Chapman University. There is history that doesn’t really get written. The Feminist Art Workers and groups that Cheri [Gaulke], works in are remembered … but not so much Double X.5

I was also inspired by my friendships with Barbara [T. Smith] and Ulysses [Jenkins], [who] has been a friend of mine forever. I took photos of his thesis show, his thesis performance at Otis. And Senga [Nengudi] of course and Maren Hassinger and May Sun – lots of people were involved in Ulysses’s performances.

[…]

I told Lucy Lippard [the feminist curator and writer] that she should really look at Senga’s work. You do what you can for people you respect and who do wonderful work. I cherish my friendship with Senga.

AGJ: Why was the rest of the feminist art world not paying attention to these other artists and activist groups. In the 1970s you had Asco over there,6 Senga and [David] Hammons over here … but seemingly few connections between these groups other than a few people like you. How much did they know about one another?

NB: I think it’s complicated.

AGJ: Can you tell me more about your immediate community as you developed your practice at university and just after that?

NB: I was in the first class at UCI with Chris and Barbara, graduating in 1971 … We were all so different at Irvine; we were doing completely different things, and yet there was total respect and support … I started out doing paintings. I wanted to paint an entire space so it would disappear – I was making airbrush paintings and I wanted to airbrush the corners of a room. But of course, who’s going to give a graduate student a whole pristine space?

AGJ: That would have been an interesting extension of light and space.7

NB: Yes, in fact Robert Irwin and Larry Bell [who taught at UCI] kind of saved my life, because I was struggling along as a single parent with a child who was a little difficult at that time. They were so supportive – whatever you want to do, do it the best you can … I’m still very close with Larry …

AGJ: What drew you to UCI?

NB: I went to undergrad there … I started at UCLA … Some things happened that skewed my life including the death of my mother, my marriage at the age of eighteen, and the birth of my son … The graduate group was really disparate. There were some older women who were finishing up their degrees for teaching. The faculty, Tony Delap, Craig Kauffman, John McCracken, kind of humored them. John Coplans hired the other faculty members, including Robert Irwin.8 When Irwin came, he made a demand which I thought was very astute: I will teach here as long as there’s no tenure, because that destroys things … Oh, and David Hockney was one of my undergrad teachers. He was a good teacher. He was very funny … I think it’s an interest in other people [that makes a good teacher], somebody who is open to others different from themselves, and interested in other things, then I think they’re great teachers. When I was teaching, I always tried to make sure to encourage students to go in their own direction. I didn’t want them to do anything like my work. I taught all over the place, part time for many years … I applied for and took a tenure track job [in 1980] at the University of Wisconsin in Madison to develop a program in non-static art and we all moved there. My performance art students presented a program at a community centre during a fierce snowstorm and the place was packed. My son stayed and still lives there. It all worked out except the marriage blew up, so I came back to California.

AGJ: For so long no one would admit that feminist and body artists could do work driven by sophisticated conceptual concerns. What I love about this Irvine moment is that all of you were deeply connecting all those things … You were all thinking really rigorous thoughts to complicate ideas about art. Using human hair to make a portrait as you’ve done … there’s something deeply philosophical about that. What does it mean to use part of a person’s body to depict that person? What’s the person? Is it the hair? Is it the representation of them?

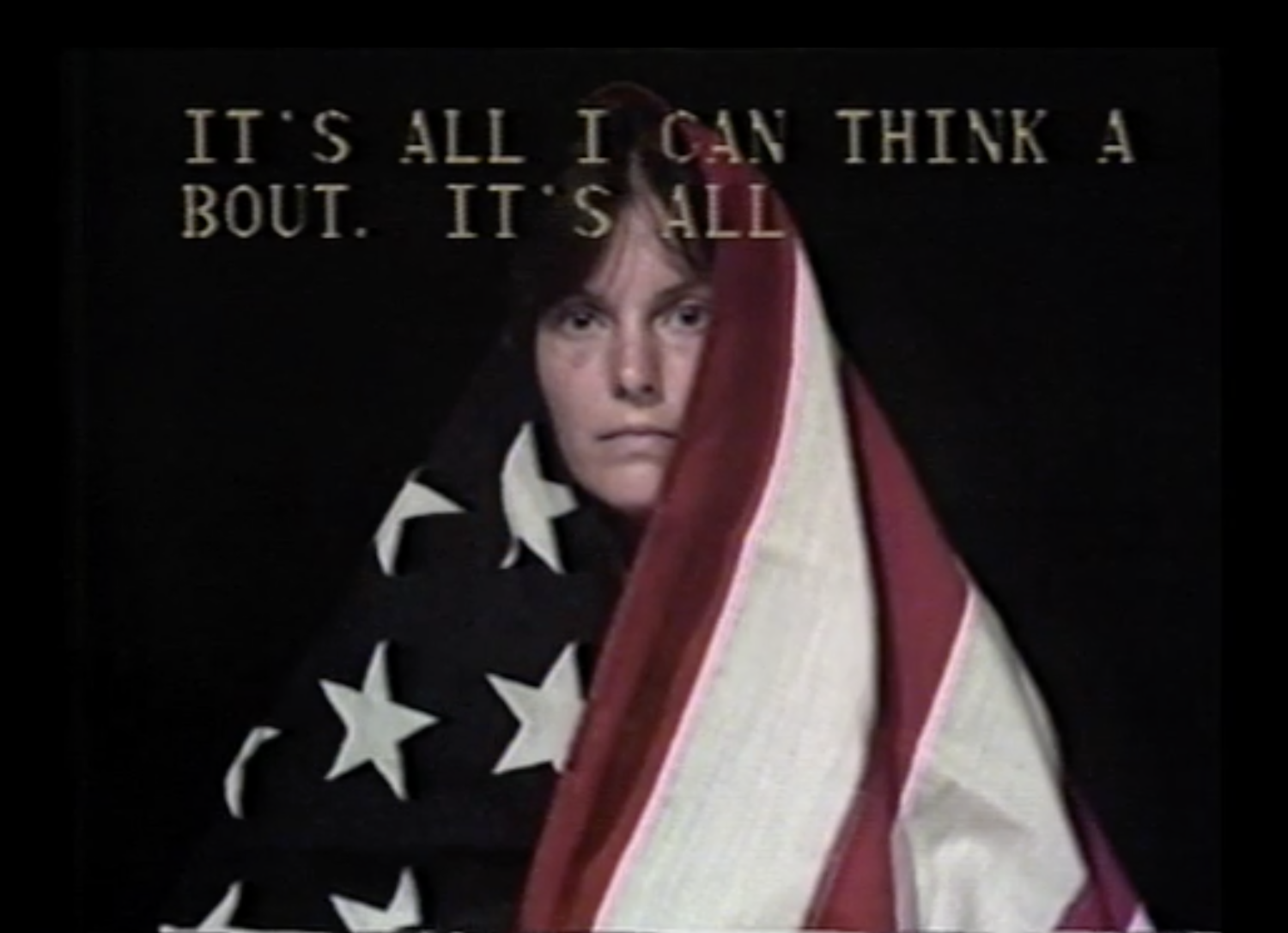

Can you tell me more about your early performances – aren’t you shaving a man’s pubic hair in Hair Transplant?9

NB: Yes, I thought of Hair Transplant as a minimalist event; everything was white, but then there were our bodies and our hair (I had red hair and he [Bob Walker] had black hair). He had grown a moustache just for the piece. The action was me shaving off the major body hair – his moustache, chest hair, underarm hair, pubic hair. I cut off my long red hair, then replaced his newly bare areas with that. I gave the audience the rest of my hair. Interestingly, there was no real response when I was doing the shaving but when I went to cut my hair off the audience gasped, “Oh no!”

AGJ: Hair has deep resonance!

NB: Yes, there are taboos and rituals to do with hair in every place in the world.

AGJ: Can you tell me more about your works with hair that are more recent? Such as those just displayed in your solo exhibition at Charlie James Gallery?10

NB: Related to hair – I had been trying to take something really charged with my very early erotic drawings, something cold and make it hot, something soft and make it hard … to bring the viewer really close. If you have to allow the work into your personal space … if the drawing is in that space, it’s another way of getting rid of intellectualisation. This is my strategy with the video miniatures I’ve made, too. You have to get really close.

[At this point, Nancy showed me her small artist’s book Hair Stories from 2019]

Nancy Buchanan, Fallout from the Nuclear Family, 1980, 10 unique artist’s books, photos, Courtesy of the artist

NB: The book is from project I started in 1972 … where I asked friends to send me their hair stories. People would send me all sort of different things. Finally, in 2017 I decided I wanted to finish it. It all started with Barbara T. Smith, who had a dinner and I asked, “What can I bring?” and she said, “You can bring some hair.” I had a friend who worked on the local marine base and who gathered a bag of hair from the barber there. I gave it to Barbara and she proceeded to repackage the hair, with a note to our friends: “Send this back to Nancy.”

AGJ: Could you tell me more about your approach and your generation? I don’t want to oversimplify, but you have always started from a covert or explicit politics, but without a lot of anguish around the system, accepting whatever the work ends up being. But today, there’s much more energy being put into systemic issues among younger artists – such as the systemic racism of the art world, which I completely agree needs to be addressed.

NB: Yeah, but you know, the world is a horrible place. You can’t expect that you can create a perfect desert island for beautiful sensitive art makers to feel safe.

AGJ: They have to find their way and find a way to make their artwork more visible.

NB: But they also have to keep being an artist. My life as an artist started when I was very young. I had tuberculosis when I was … four … They sent me to live with my maternal grandmother and she was wonderful. She would bring reams of typing paper and sit with me and we would draw pictures together and she would write the stories for me. … She saved my life … My Grandmother Page was wonderful – she was much more giving than most parents were at the time and very openminded.

AGJ: One of the most vibrant things about you on the LA art scene is your kindness and generosity. I told you, Senga Nengudi pulled you out – “I really struggled with the Woman’s Building and there wasn’t a lot of acknowledgment”; as Senga told me, Black and Latinx women often had children and many of the white women did not … Your supportiveness has stayed with her until this day – there was something about you that was different. Most white people in the art world are liberal but the vast majority of white people don’t really understand or acknowledge white supremacy … it’s that empathy that you have that is so often missing. Obviously it comes naturally to you.

NB: I’m grateful for all my friendships. I met Senga through Ulysses. I met Barbara McCullough through Double X.

AGJ: Tell me more about the 1970s and how your feminism developed in relation to these friendships. To me this all relates because being a feminist is a life politics, creating a community – your career really exemplifies that.

NB: At Irvine nobody did anything like anyone else. But here was this complete solidarity. Irwin profoundly affected all of us in terms of – better than [Marcel] Duchamp – making us understand that art is not in the thing, it’s in the experience – that’s where it resides.

When I was at UCI I didn’t have much of an income. I had a small budget from my mother’s estate … Bob [Robert] Morris was pushing scatter stuff. Irwin and Bell were minimalists. Bob [Robert] Walker and I were scheduled to do something for F Space Gallery [in 1971] and we drove by a recycling place with huge piles of shredded newspaper. We bought something like 5 tons of it and made a nest in F Space. That was kind of like hair in a way.

When it was time for me to do my thesis piece, I was in the graduate gallery, which was terrible. It was like a gym – I mean, it had those lockers and a big clock, and ugly linoleum on the floor. And I thought, you can’t put your paintings in there … there’s no good lighting system. You have to do something else. So I thought, I’ll make a rug out of human hair and put poodle hair in the middle for a contrast. If people are interested they could take their shoes off and feel it. It’s this minimalist thing, these colours of grey and brown …

Barbara Rose, the art critic, was visiting and took one look at it and said, “I’ve never seen anything so disgusting”. It was like – whoa that’s interesting. Instead of being a cerebral piece it was more visceral. I was shocked because I hadn’t thought of that aspect of it … And then it occurred to me, well, this is a whole new direction and I like that. It’s visceral so it breaks down that intellectualizing [that people do when] they see art. Hair’s a really good medium to use [as a feminist strategy].

Chris [Burden] had the gallery after me, and he said: “I’m not going to use the space, I’m just going to use the lockers, so you can keep your piece there.”11 …

Our group graduate show was another example of solidarity. Due to the controversial nature of Chris’s proposal to ride a racing bicycle through the gallery, the dean said, you can’t do that because we can’t take liability for that, so all of us other students said, “OK, we’re out of here”. But they had already advertised it so the dean had to figure out how to let Chris ride his bike. He wanted to continually ride around the gallery. He had a fascination for vehicles … The upshot was that Chris had to post some little signs and viewers had to sign a waiver. He rode on a tar paper loop in one door and out the other.

AGJ: You went from that Irvine context [graduating with an MFA in 1971] to being an artist in Los Angeles – can you tell me more about that period?

NB: Everybody helped everybody else. I was in a few of Barbara’s performances, reluctantly losing my clothes … and then Judy [Chicago] contacted Barbara because Judy and Barbara had had studios next to each other in Pasadena. She invited Barbara to join a new co-op gallery at Grandview [the gallery at the first site of The Woman’s Building], but Barbara didn’t want a full membership, so she shared it with me … that was around 1973.

In the gallery we used to have these sessions where everybody would talk about what they were doing … just talking through the work.

AGJ: So there you are, at Grandview … was that kind of a major site for you until the end of the decade?

NB: The building moved and there was a bunch of us who wanted to do projects in the community rather than just show our own work – our first project was to publish Faith Wilding’s book about women’s art in Southern California: By Our Own Hands.12 In the 1970s I did performance work and also began using video – which then led to many new opportunities, such as teaching community workshops and working with activist Michael Zinzun from 1988-1998 on his live Community Access cable tv program, Message to the Grassroots. We also taught workshops together in Watts, and through Michael’s LA435 group, I travelled to Namibia and produced a short documentary about Africa’s last colony moving to full independence.

AGJ: What a life! What a career crossing over art, activism and teaching. Los Angeles and the feminist community in particular is lucky to have you.

Senga Nengudi, 2009 interview with Amelia Jones for the Live Art in Los Angeles project, sponsored by Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions and the J. Paul Getty Research Institute’s Pacific Standard Time (PST) initiative on arts in Los Angeles, 2011.

2

See Nancy Buchanan, “Double X Redux”, in XX Redux: revisiting a feminist art collective (exh. cat. Orange, CA: Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University, 2015), pp. 6-7. As she notes here, “Double X, an art collective that flourished from 1975-1985, was committed to expanding the visibility of art made by women. … A group of artists who had been members of Grandview I and II Galleries at the original location of the Los Angeles Woman’s Building formed Double X, following the [Woman’s] Building’s relocation on Spring Street,” p. 6. She continues: “We represent a gamut of contemporary directions; the sole commonality [of artists in Double X] is based in the fact that all of our works grow from personal experience and/or social perspectives – the bedrock of feminist theory,” p. 7. Of note, Womanspace Gallery had preceded Grandview Galleries and Double X; Womanspace was a short-lived initiative, which was founded in 1973, moving to the Woman’s Building later that year; it folded in 1974. See Eizabeth Dastin, “From the Laundromat to the Woman’s Building: Historical Precedents for Double X Collective”, in XX Redux, pp. 46-49.

In an email to the author on 4 June 2021, N. Buchanan expanded on the complex politics of the Woman’s Building: “Actually, thinking about the Building, it IS so complicated. I wouldn’t want us to go too far in criticizing them. But – Mother Art [a feminist collective founded in 1974] formed there because a few members of the first feminist art class at the building had kids – but [some of] the Building’s … [members] had made rules that women were invited to bring their dogs, but not their children. (I later found that my own son had carved a little snake in the bricks by the parking lot and had written ‘Page, a boy, 8 years old’; so he must have felt excluded somewhat!) So these artists [in Mother Art] (Laura Silagi, Christie Kruse, Suzanne Siegel, Helen Million Ruby, and Jan Cook) made a kid’s playground. There is some cool super-8 footage of them driving forklifts and building it. [Also] Judy Chicago told Helen Million-Ruby that she couldn’t be an artist unless she left her family.” For more information on Mother Art, see the video of the panel “Woman’s Building History” of original members from Otis College, 2010; available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qWHeimOXgn0

3

See the timeline of Double X exhibitions and events, XX Redux, p. 53.

4

Barbara McCullough is a Black independent film director, production manager and visual effects artist linked to the so-called L.A. Rebellion filmmakers; she has worked across the art and film worlds in Los Angeles since 1970. According to N. Buchanan, McCullough made a documentary video featuring Betye Saar, David Hammonds, Sunga Nengudi, and her own work: Shopping Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes: Reflections on Ritual Space. Her most recent work is Horace Tapscott: A Musical Griot (2017).

5

The Feminist Art Workers were a performance collective including Nancy Angelo, Candace Compton, Cheri Gaulke, Vanalyne Green and Laurel Klick. It was founded at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles in 1976 and made work together until 1981. The collective’s work is remembered partly because it was featured in an exhibition and catalogue sponsored by the J Paul Getty Institute as part of the 2011 Pacific Standard Time events showcasing Los Angeles art, called Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building (at Otis College of Art and Design). See also Cheri Gaulke’s website: https://cherigaulke.com/portfolio/feminist-art-workers/

6

Asco was a radical Chicana/o art collective founded in the early 1970s by Harry Gamboa Jr., Patssi Valdez, Gronk (Glugio Nicandro) and Willie Herrón. Nengudi and Hammons, along with Jenkins, McCullough and Hassinger, often worked together and formed a vibrant community of Black artists, along with luminaries such as Noah Purifoy and Charles White, working in Los Angeles.

7

The Light and Space movement was a loosely defined group of Los Angeles artists working with scrims, glass and reflected light, airbrushed paint, Plexiglas, and other materials associated with Southern California’s aero-space industries, including Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, Mary Corse and, for a brief period in the late 1960s and early 1970s, feminist icon Judy Chicago.

8

Based in California in the 1960s through 1971, John Coplans was a British artist and a major player in the 1960s and 1970s US art world, co-founding Artforum, writing art criticism, and teaching as well as running the University Art Gallery at UCI and then acting as senior curator and then director at the Pasadena Art Museum. He left California for New York in 1971.

9

Hair Transplant was performed at F Space in 1972. The gallery was formed by N. Buchanan, Chris Burden and a handful of other UCI students, who were disappointed with the inadequate gallery space on campus. See Nancy Buchanan, “A Few Snapshots from F Space Gallery, 1514 E. Edinger, Santa Ana,” In the Canyon, Revise the Canon: Utopian Knowledge, Radical Pedagogy, and Artist-Run Community Art Spaces in Southern California, ed. Géraldine Gourbe (Annency: ESAAA Editions and Lescheraines, France: Shelter Press, 2015), pp. 49-55.

10

The show was Nancy Buchanan: Crowning Glories, 15 July-29 August 2020; Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles. See: https://www.cjamesgallery.com/show-detail/crowning-glories

11

This would be Chris Burden’s infamous Five Day Locker Piece, in which he situated himself in a locker for five days, with a container below the locker for his pee, and another above with water for him to drink.

12

Faith Wilding’s By Our Own Hands: The Woman Artist’s Movement, Southern California, 1970-1976 (Santa Monica, CA: Double X, 1977) remains one of the most important sources on the history of the feminist art movement in Los Angeles.

Amelia Jones is Robert A. Day Professor and Vice Dean at Roski School of Art & Design, USC. Publications include Seeing Differently: A History and Theory of Identification and the Visual Arts (2012) and Otherwise: Imagining Queer Feminist Art Histories, co-edited with Erin Silver (2016). The catalogue Queer Communion: Ron Athey (2020), co-edited with Andy Campbell, and which accompanies a retrospective of Athey’s work at Participant Inc. (New York) and ICA (Los Angeles), was listed among the “Best Art Books 2020” in the NY Times. Her book entitled In Between Subjects: A Critical Genealogy of Queer Performance (2021) is published by Routledge Press.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring