Judy Chicago

Lippard Lucy R. (ed.), Judy Chicago, exh. cat., National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C. (2002), New York, NY, Watson-Guptill, 2002

→Levin Gail, Becoming Judy Chicago: A Biography of the Artist, New York, Hamarmony Books, 2007

→Dickson Rachel (ed.), Judy Chicago and Louise Bourgeois, Helen Chadwick, Tracey Emin, exh. cat., Ben Uri, The London of Jewish Museum of Art, London (14 November 2012–10 March 2013), Farnham Burlington, Lund Humphries, 2012

Why not Judy Chicago?, CAPC, Musée d’Art Contemporain de Bordeaux, 12 March–4 September 2016

→Inside The Dinner Party Studio, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC, 17 September 2017–5 January 2018

→Judy Chicago and Louise Bourgeois, Helen Chadwick, Tracey Emin: A Transatlantic Dialogue, Ben Uri, The Jewish Museum of Art, London, 14 November 2012–March 10 2013

American visual artist.

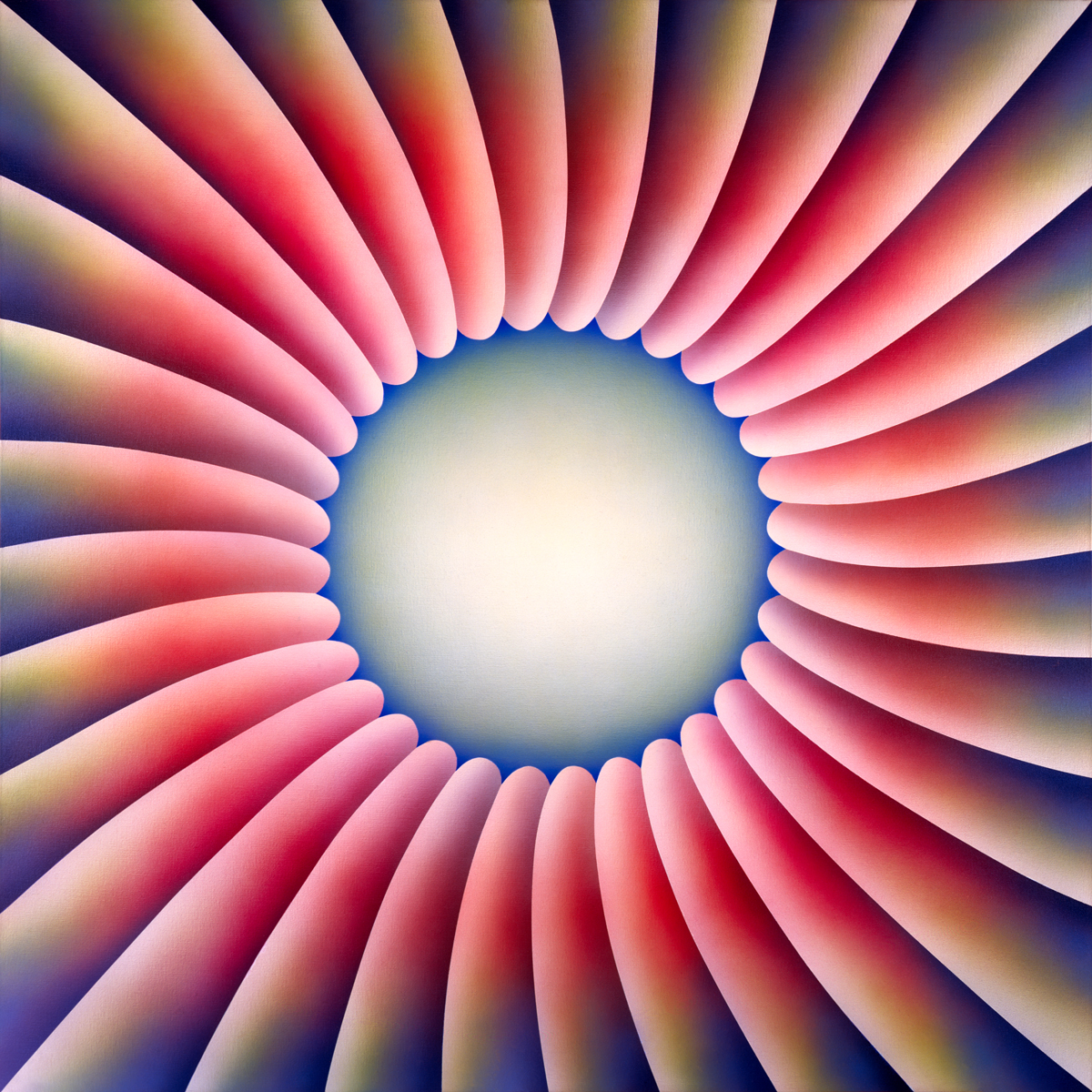

In 1964, Judy Cohen graduated from the University of California’s art school. She then gained recognition for her near-minimalist art pieces such as Rainbow Pickets, exhibited for the first time during Primary Structures (exhibition, Jewish Museum, New York, 1966), a landmark event for minimal art. Today she is known as one of the founders of the feminist art movement in the United States. Calling into question the language of minimalism, which she felt was too exclusively formalist, she then devoted herself to the exploration of her feminine experiences. In 1969, she created the first feminist education programme in California, the Feminist Art Program, at Fresno State College, before repeating the experience from 1971 to 1973 with artist Miriam Shapiro (1923) at CalArts (California Institute of the Arts): the two women would encourage their students to give a voice to their experiences and support their ambitions. In the famous Womanhouse exhibition (1972), 17 projects illustrated the experiences of women within a discriminatory society (household chores, the construction of femininity), echoing Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique (1963). Both artists advocated a specific representation of women based on vaginal centrality. This assertion is amply debated within feminist circles: some criticize its essentialism – you are born as a woman, you do not become one – objecting to the biological determination of these images in favour of a cultural and social construction.

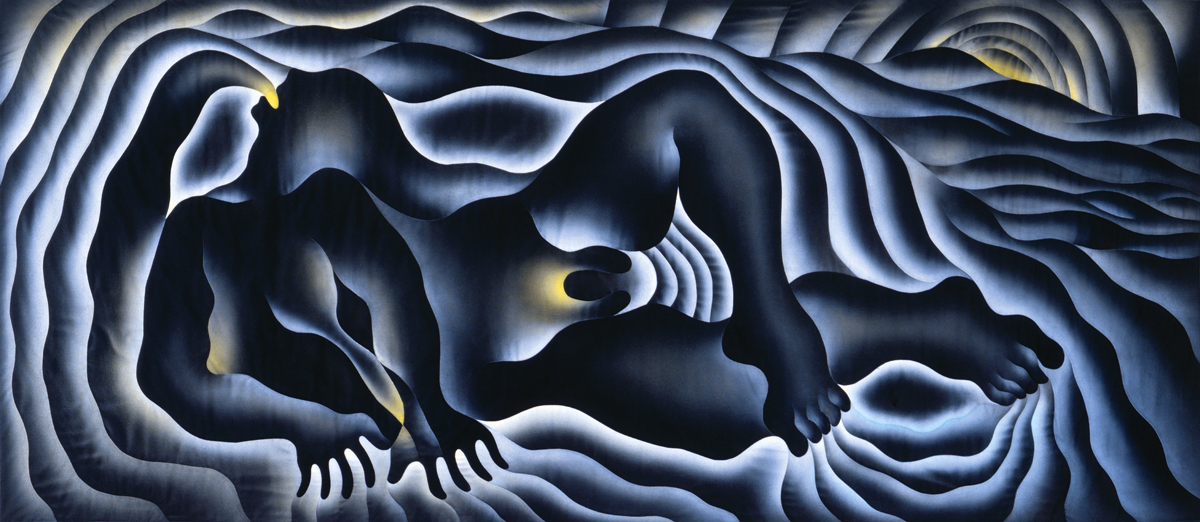

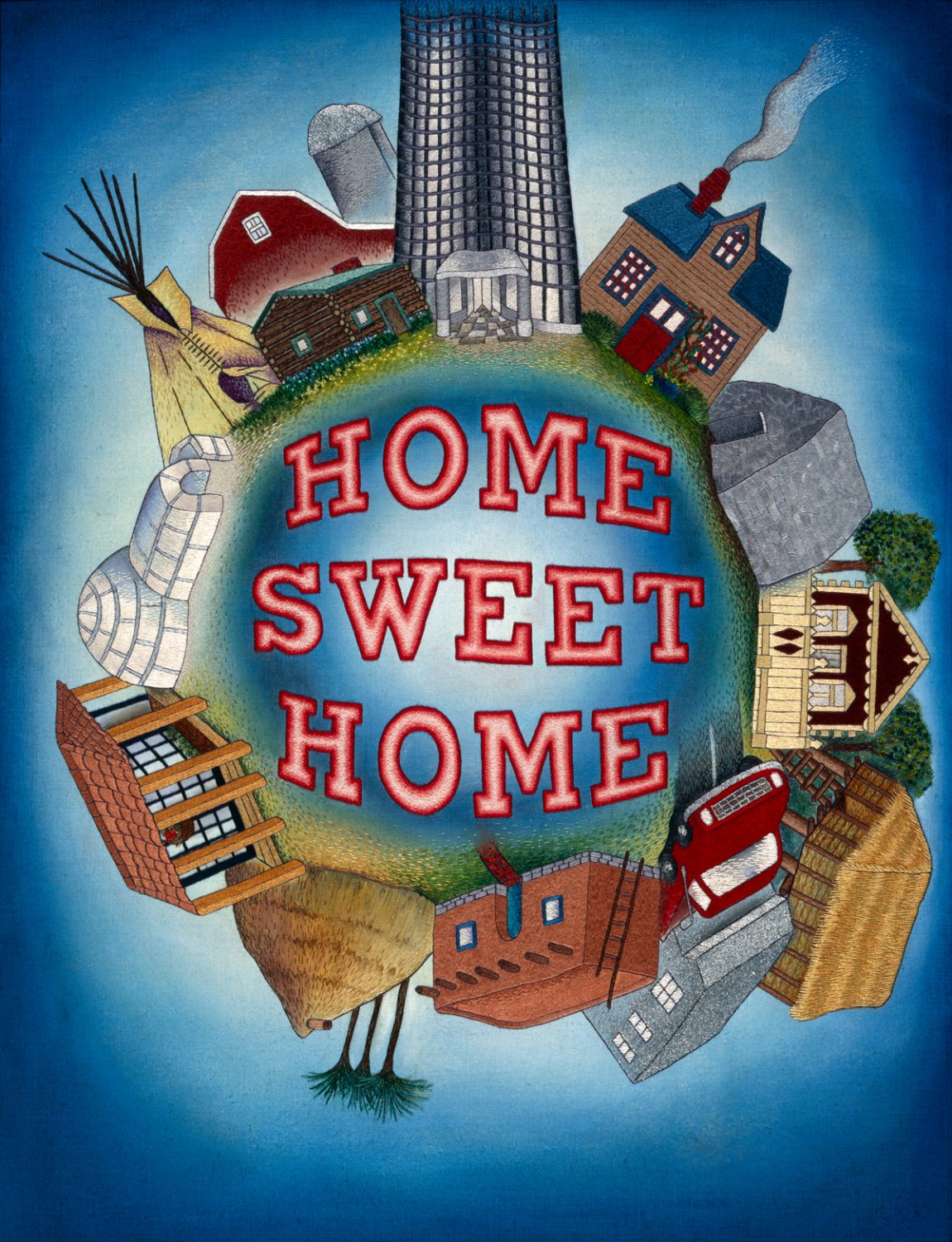

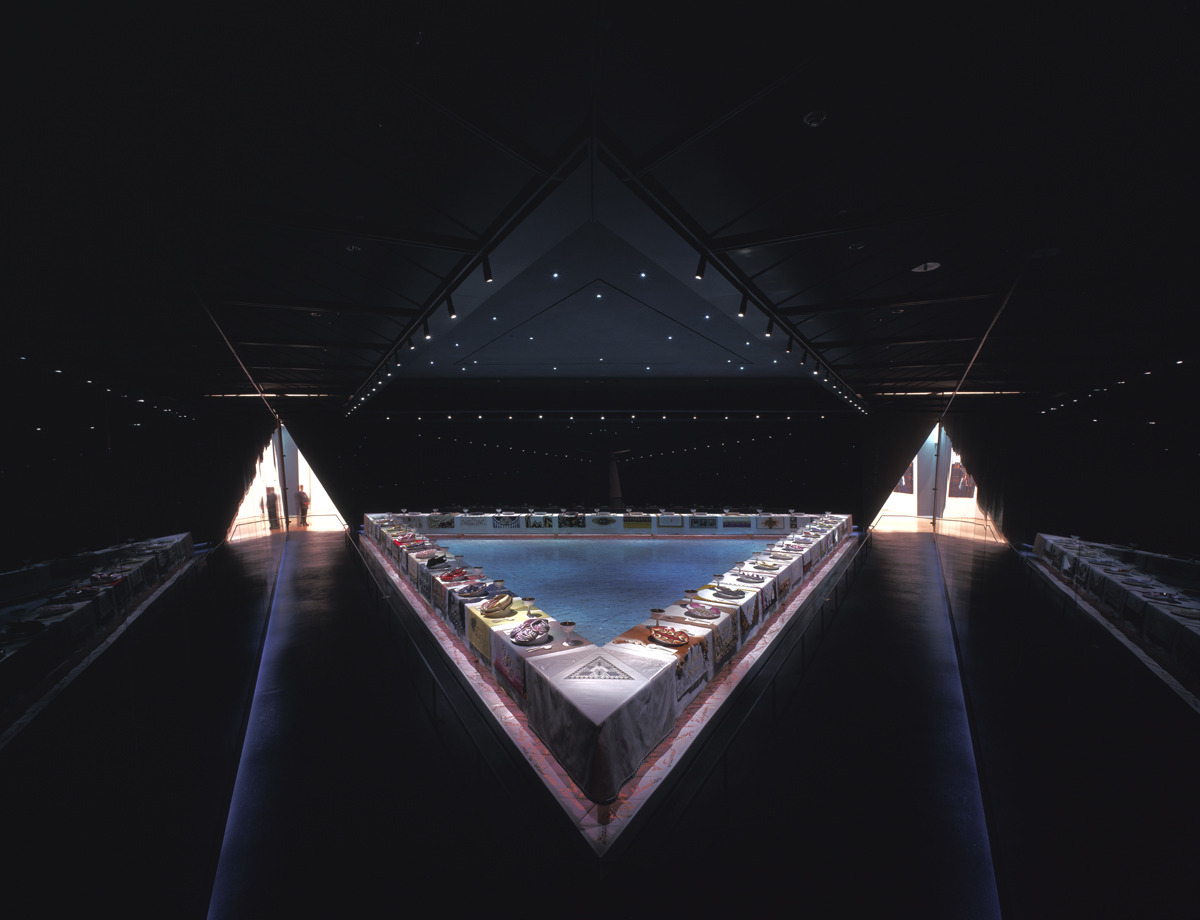

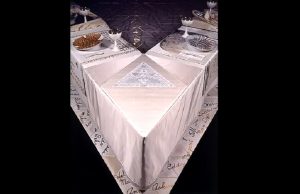

In 1973, together with Sheila Levrant de Bretteville (1940) and Arlene Raven (1944–2006), Judy Chicago inaugurated the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles, a multi-purpose space for exhibitions and art education exclusively reserved for women. She became famous with The Dinner Party (Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum, New York 1974–1979). The 39 place settings of this enormous triangular Last Supper pay tribute to important historical and mythological women. The ceramic, porcelain, and textile art work, which was made in collaboration with about one hundred women, has become an icon of feminist art from the 1970s, but also garnered its share of detractors. In the 1980s, several of her realistic pictorial series featured specific issues. Thus, Birth Project (1980–1985) depicts the experience of giving birth, between pain, realism, and spirituality; Powerplay portrays the construction of masculinity and its abuses of power. In her autobiography, the creator explains what compelled her to make art: her fight for the recognition of a certain view of women, while providing a visual showcase for work considered “feminine.” She is aware of the simplifications inherent in her message, and owns up to these limitations, which she considers necessary to insert the female experience into art, alter how reality is perceived, and operate cultural change.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Judy Chicago's exhibition tour

Judy Chicago's exhibition tour  Judy Chicago: A Butterfly for Brooklyn (Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist)

Judy Chicago: A Butterfly for Brooklyn (Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist)  The Dinner Party, A Tour of the Exhibition, narrated by Judy Chicago

The Dinner Party, A Tour of the Exhibition, narrated by Judy Chicago