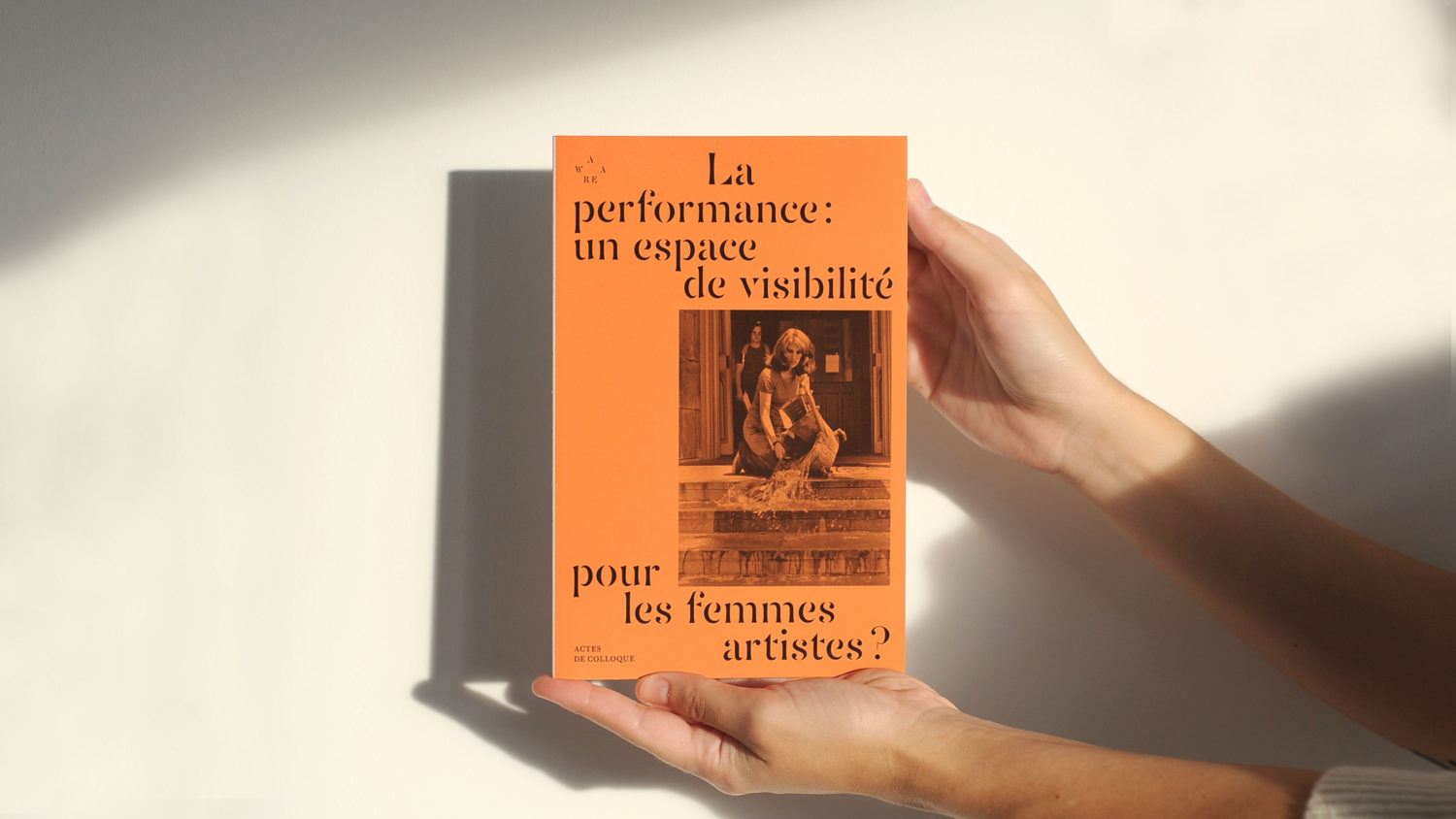

Publications

This publication follows a conference that took place on May 14th, 2018 at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. Entitled, “La performance : un espace de visibilité pour les femmes artistes ?” [Performance: a place of visibility for female artists?], the conference was part of the interdisciplinary research programme “Visibilité et invisibilité des savoirs des femmes : les créations, les savoirs et leur circulation, XVIe-XXIe siècles” [Visibility and Invisibility of Women’s Knowledge: Creations, Knowledge and Circulation, 16th-21st century]. Led by Caroline Trotot in the heart of the Littératures, Savoirs et Arts (LISAA) research lab at the Université Paris-Est – Marne-la- Vallée from 2017-2018, this programme benefited from the support and active collaboration with the association AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, for both the conference and the present publication. One of the objectives was to study how creative work or the use of the body can give way to strategies of diversion allowing to question mechanisms of visibility and invisibility that regulate women’s knowledge. As a result, performance has become a field interweaving these aspects of the body and of the work of art, particularly since it has been largely invested by women throughout its history.

- “Cleaning is working” Camille Paulhan

- Beyond the Frame: Feminist Strategies in the Expanded Cinema of the 1960s and 1970s Maud Jacquin

- The Body in Performance: The Impossible Quest for Identity Thérèse St-Gelais

- Suffering Bodies and Transgressive Femininity in the Performative Works of Yvonne Rainer, Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke Johanna Renard

- The Performances of Gina Pane through the Prism of Apulian Tarantism: Between the Repressive Economy of Blood and the Visibility of Popular Feminine Rituals Janig Bégoc

- Counter Archives: Archaeological Ficttion of Embedded Submission Laboratoire de la contreperformance

Introduction

Juliette Bertron et Carole Halimi

This publication follows a conference that took place on May 14th, 2018 at the Beaux-Arts de Paris. Entitled, “La performance : un espace de visibilité pour les femmes artistes ?” [Performance: a place of visibility for female artists?], the conference was part of the interdisciplinary research programme “Visibilité et invisibilité des savoirs des femmes : les créations, les savoirs et leur circulation, XVIe-XXIe siècles” [Visibility and Invisibility of Women’s Knowledge: Creations, Knowledge and Circulation, 16th-21st century]. Led by Caroline Trotot in the heart of the Littératures, Savoirs et Arts (LISAA) research lab at the Université Paris-Est – Marne-la- Vallée from 2017-2018, this programme benefited from the support and active collaboration with the association AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, for both the conference and the present publication. One of the objectives was to study how creative work or the use of the body can give way to strategies of diversion allowing to question mechanisms of visibility and invisibility that regulate women’s knowledge. As a result, performance has become a field interweaving these aspects of the body and of the work of art, particularly since it has been largely invested by women throughout its history.

If we consider performance in its strictest definition—“an artistic manifestation in which the execution of an act or gesture has value in and of itself”— we can immediately understand how this medium lies directly on the border of where the artwork and the body merge not only as operators of knowledge, but also as instruments of interaction with the social, the audience and the environment. The performative act, in its visibility and invisibility, is the place of tangible interrogation able to convey and divert knowledge, as well as raising questions. If this medium has been able to serve a field of feminist revendications, it is because in performance women have found themselves simultaneously as actors, creators and subjects. The method of visibility and exhibition of the self at play in performance allows us to create a hollow space where women can physically and conceptually engage in a questioning of their own condition.

By becoming a popular artistic embodiment of the feminine, performance has only exacerbated a strategy that has been at work for a long time. When we consider attitudes by lady Hamilton at the end of the 18th century, or even the tableaux vivants from the 19th century, it is clear that women already occupied positions as both creators and subjects. Often at the initiative of men and intended for their enjoyment, these representations could have nevertheless created a liberating space where women could free themselves from the existing norms. This space of body exposure and its physical valorisation through movement and pose was readily given to women to satisfy the pleasures of the male gaze’s scopic drive. Several female performers, as seen with numerous articles in this publication, have openly played with this dual reality between seduction and denunciation. Thus, one can question the intrinsic link that binds performance to women. In an aphorism from The Gay Science by Fredrich Nietzsche that addressed the unveiling of the invisible and the beautiful in the space of life and the visible, comes the following affirmation: “Yes, life is a woman!” In this publication, we wish to divert this statement coming from a place of masculine thinking, as gay as it was, to address another hypothesis — “Yes, performance is a woman!”

Beyond the medium itself, it is to the history of performance that this affirmation can thus be linked. It was RoseLee Goldberg that published one of the first books on the history of performance in the 20th century in 1979. For quite some time, this art form was thus found in the margins of canonical art history. The questions raised through consciences and bodies left only traces that could no longer be considered at the same level as traditional works of art. It was necessary to reconsider the traces and archives as a new mode of transmitting knowledge in order to make the invisible reality of performative practices visible. Over time, certain female artists emerged as established founding figures in the history of performance, among them are Gina Pane (1939-1990), Hannah Wilke (1940-1993) and Yvonne Rainer (born 1934), who will be discussed in this publication.

It is clear that a conference or a publication about performance must be in touch with the impetus of the medium and its impact on reality. The collective Laboratoire de la contre-performance (Counter Performance Lab, founded in 2014) thus delivered a lecture-performance under the provocative title Les Contre-archives [The Counter-archives] at the Beaux-Arts de Paris on May 14th, 2018. Initially, the framework of the conference favoured three axes of research: the exposed body, the intimate and sexuality, and social interaction. The authors of this publication adapted these various lines of thinking, reconsidering the dialectics of visibility and invisibility of women’s knowledge in and through the medium of performance. Through the performative act, women are confronted with their environment, allowing a re-examining of societal, historical, cultural and anthropological frameworks.

The publication opens with a text by Camille Paulhan, focusing on the recurrent use of domestic acts in performances from the 1960s and 1970s, and more specifically the actions of Mierle Laderman Ukeles (born 1939). C. Paulhan’s approach is nourished by feminist slogans as well as archetypes from popular culture. She highlights how these performances combine a politicised reflection on invisible and gendered savoir-faire and domestic work with a reflection on the institutional legitimacy of female artists.

The constraints and invisibilisation that affect women in the social field are also questions raised in the article by Maud Jacquin. Through the analysis of works by Gill Eatherley (born 1950), Sally Potter (born 1949), Trisha Brown (1936-2017), Barbara Hammer (1939-2019) and the duo formed by Maria Klonaris (1950-2014) and Katerina Thomadaki (born 1949), the author illustrates how the practices of expanded cinema, by orchestrating the confrontation between the physical presence of live performers and their filmed images, engendered not only the surpassing of the traditional cinematographic screen, but also the straitjacket too often imposed on the female body.

As seen in Thérèse St-Gelais’s contribution to the publication, this emancipatory potentiality of performance as a means of critiquing norms and stereotypes is mobilised in the works of Nadège Grebmeier Forget (born 1985) and Rebecca Belmore (born 1960). Based notably on foundational theories of Judith Butler, the author highlights the possible emergence of real representations of women and their sexuality, as well as the unveiling of new subjectivities. In the performances of N. Grebmeier Forget, the colourful and outrageous staging of feminine excessiveness disrupts the social expectations of seduction and beauty. With R. Belmore, the same seduction is displaced towards a troubling aestheticization of suffering and wounds employed to reveal the underlying violence against women, particularly indigenous Anishinaabe women.

These same decrees of beauty, youth and health specific to patriarchal societies are highly criticised through the works of Y. Rainer, Jo Spence (1934-1992) and H. Wilke, as discussed by Johanna Renard. The suffering bodies of these artists, all suffering from cancer in the 1980s and 1990s, were exposed to scrutiny and invested with a strong contentious force, not without a certain subversive impertinence. Performative practices thus become a means of documenting illness while fighting against a dispossession of the body suffering in a medical context.

The theme of suffering takes on a different role in the performances of G. Pane between 1968 and 1979, here studied by Janig Bégoc. The author reveals a survival of popular feminine rituals with healing and cathartic functions, particularly regarding the phenomenon of tarantism. She weaves the links between these performances and the both symbolic and mythological figure of the spider, proposing a new reading of the artist’s use of wounds and blood, enriched by the anthropology of feminine knowledge. The last article in this publication written by the collective Laboratoire de la contre-performance documents the lectureperformance Les Contre-archives. With caustic humour, the links between performance and archives are questioned through the use of fiction, as well as a theoretical discourse and re-enactment carried out with artefacts.

This contribution invites us to reconsider the role of the archive in the dialectic of visibility and invisibility from a historiographical perspective. Through her analysis, C. Paulhan mentions the absence of archives related to the performances of M. Laderman Ukeles at the Wadsworth Atheneum museum of art—a revealing absence in regards to the housework that is unnoticed by society and the fate that is too often reserved for female artists. According to J. Bégoc, it is precisely from the photographs of the performances by G. Pane that she is able to detect a “slightly visible” oscillation and swaying in the artist’s body that gives her importance. It is thus through the full scope of these documents—at times having the status of a work of art in and of themselves—from which a history of performance can be extracted. The fifty-year period, from the late 1960s until today, covered by the works examined here provides an additional testimony— if still needed—to the essential role held by female artists in the artistic field.

It must be noted that the contributions brought together in this publication shed light on a new history of current and ancestral feminine knowledge, whether intimate, medical, ritual, domestic or artisanal. Against the backdrop of the strong ties to the demands of feminist activism, performance appears in all of its active and profoundly reformative strength as a tool of protest and empowerment allowing women artists to assert themselves as subjects.

In conclusion, we would like to warmly thank the participants of the conference and the authors of the present publication; Caroline Trotot; Kathy Alliou, Jean-Marc Bustamante, Jany Lauga and Armelle Pradalier from the Beaux-Arts de Paris; the AWARE team, and notably Hanna Alkema, Camille Morineau and Sorana Munteanu.