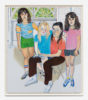

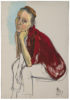

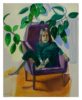

Alice Neel

Allara Pamela, Pictures of people, Alice Neel’s American portrait gallery, Hanover, University Press of New England, 1998

→Lewison Jeremy (ed.), Alice Neel : peintre de la vie moderne, exh. cat., Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki (2016) ; Gemeentenmuseum, La Haye (2016 – 2017) ; Fondation Vincent van Gogh, Arles (2017) ; Deichtorhallen, Hambourg (2017 – 2018), Brussels/Arles, Fonds Mercator/fondation Vincent van Gogh, 2016

→Larrett-Smith Philip, Lewison Jeremy (ed.), Alice Neel in New Jersey and Vermont, exh. cat., Xavier Hufkens, Brussels (26 October – 15 December 2018), Brussels, Xavier Hufkens, 2018

Alice Neel’s Women, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D. C., 28 October 2005 – 15 January 2006

→Alice Neel Collector of Souls, Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 6 September – 7 December 2008

→Alice Neel: Painted Truths, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 21 March – 13 June 2010

American painter.

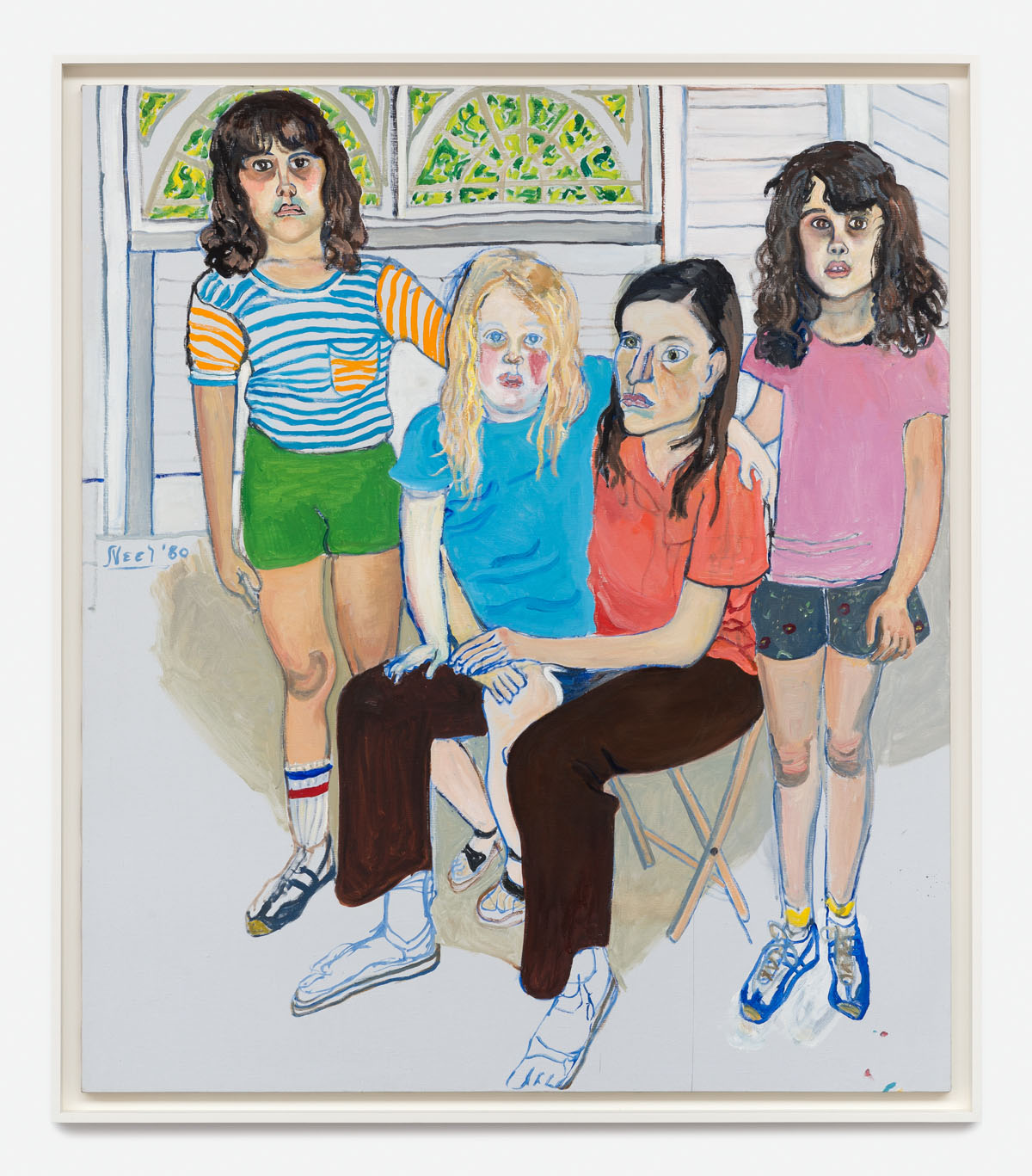

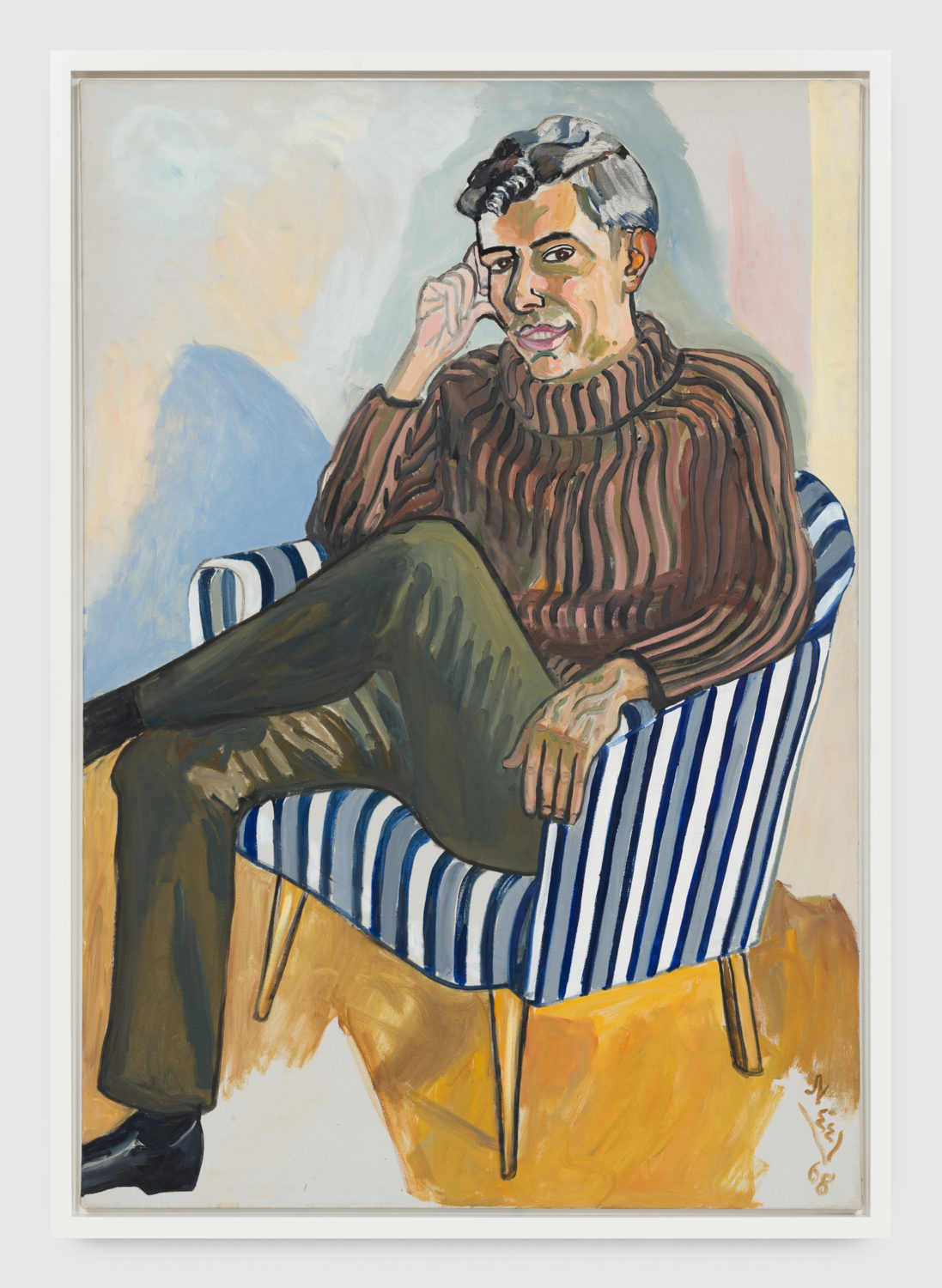

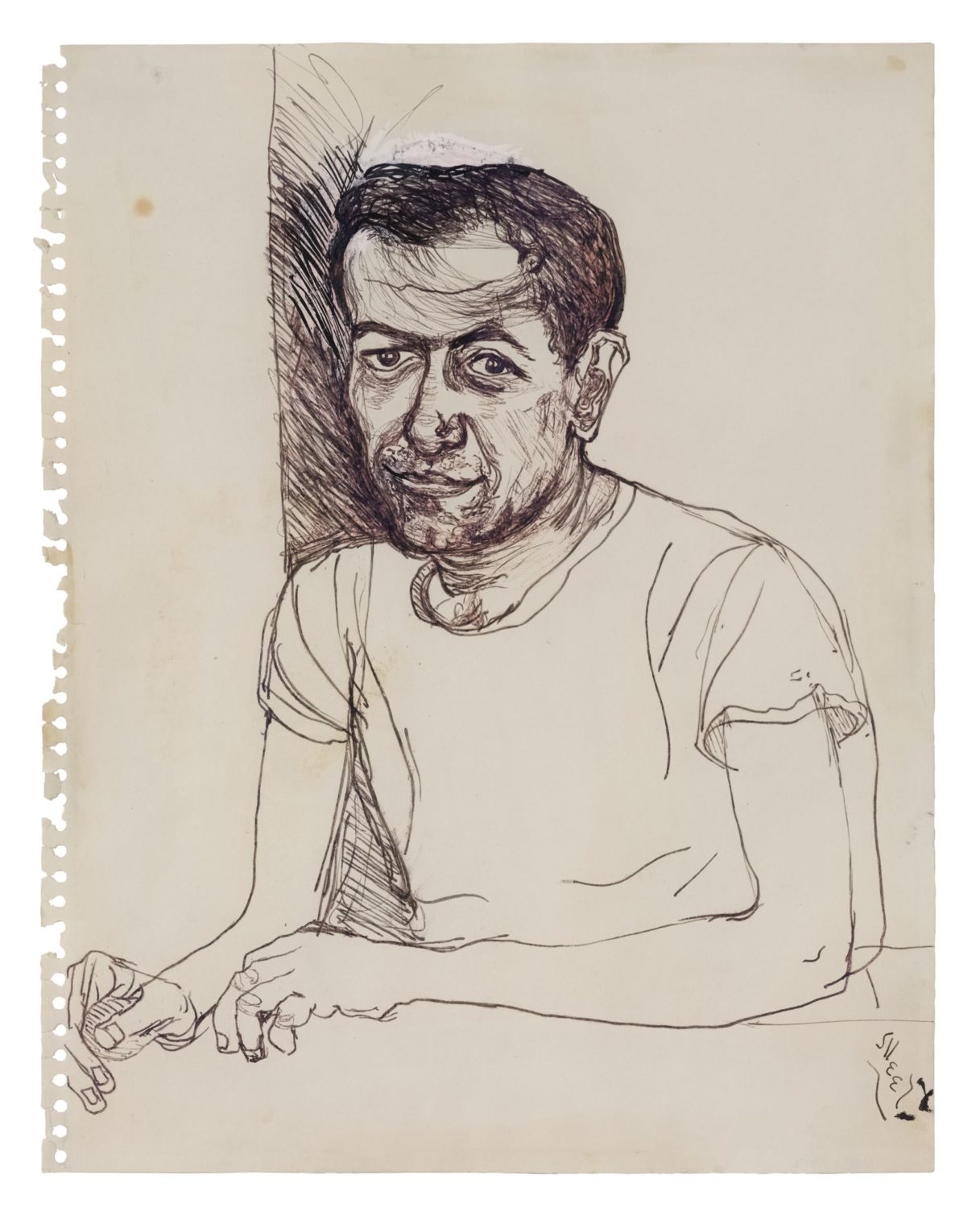

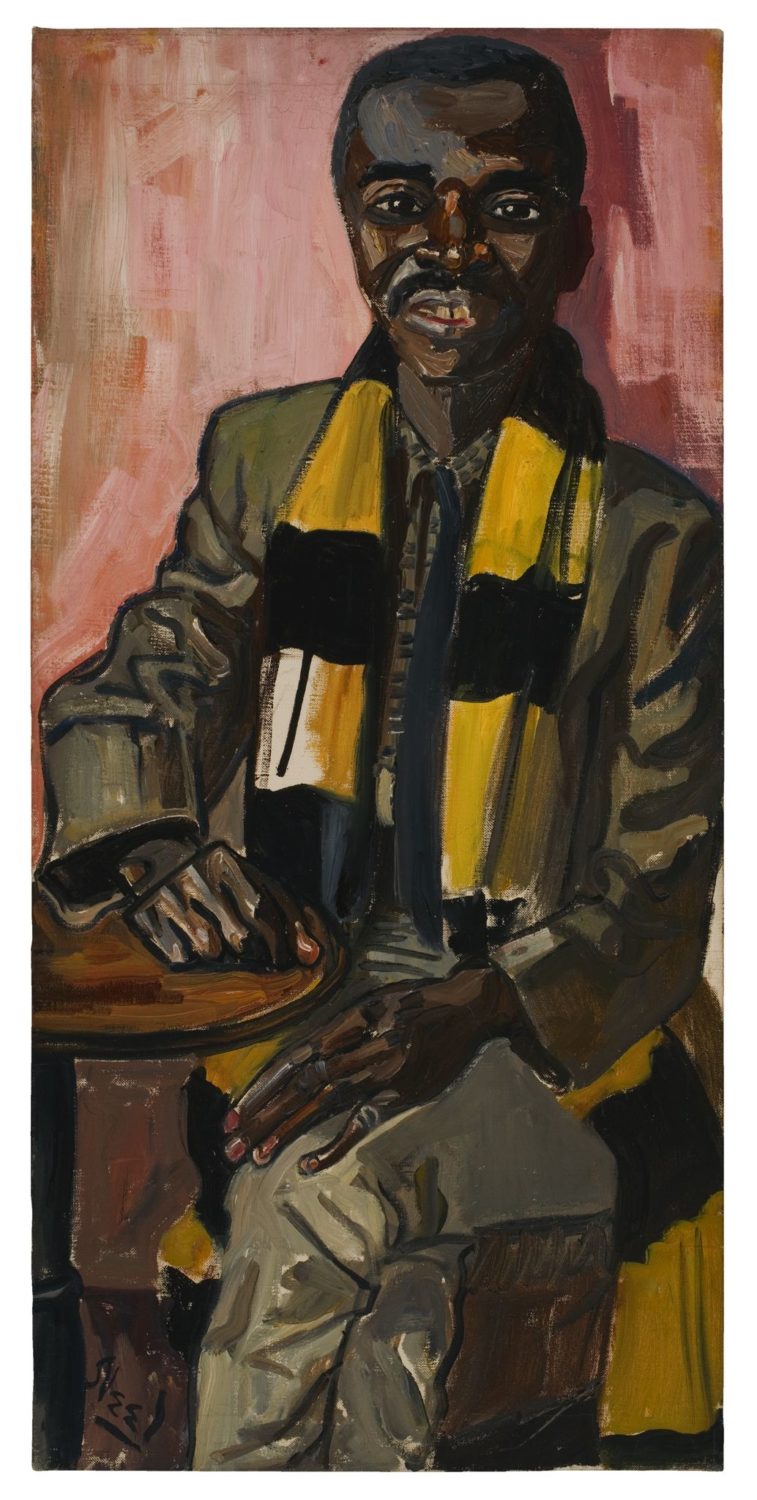

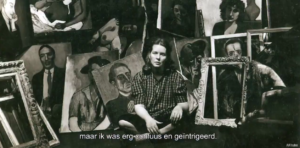

After studying at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, Alice Neel travelled with her husband, painter Carlos Enríquez (1900–1957), to Havana, where she socialized with the Cuban artistic avant-garde. The terminal illness of her first daughter Santillana would hang over her subsequent work, haunting them with the issue of maternity for the rest of her life. Neel moved to New York in 1926. The birth of her second daughter, Isabetta, inspired a painting that was both cruel and grotesque – Well Baby Clinic (1928) – in which the maternity ward took on the appearance of a psychiatric hospital. In 1930, Enríquez returned to Cuba with their daughter. Neel then fell prey to depression and attempted suicide. Following a year-long stay in a psychiatric institution in Philadelphia, she returned in 1931 to New York, where she would paint a series of portraits of New York locals, among them Joe Gould, Greenwich Village’s “heavenly tramp”, whose naked body was riddled with a multitude of penises. In the era between 1930 and 1940, her works, mainly portraiture, took on a distinctly sexual and political dimension.

This is how she ended up developing emotional and political ties with the members of the American communist party, many of whose portraits she would paint. Her love affair with filmmaker, photographer, and critic Sam Brody (with whom she would have a child), went hand in hand with an intense militant activity within the American communist press. Towards the end of the 1960s in particular, Neel became a major icon owing to the growing influence of the women’s liberation movement. Her portrait of feminist Kate Millet* for the cover of Time Magazine put her in the spotlight. In 1974, the Whitney Museum of American Art featured her in a comprehensive retrospective. Since her death in 1984, recognition of the painter’s importance has been constantly increasing. Her grandson, Andrew Neel, made a film about her in 2007, and her posthumous exhibition (Alice Neel Painted Truths), organized by the Houston Museum of Fine Arts in 2010, was also shown at the Whitechapel Gallery in London and the Moderna Museet de Malmö in Sweden.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Alice Neel, Collector of Souls

Alice Neel, Collector of Souls