Alla Horska

Iakovlenko, Kateryna, “Art Between Manliness and Activism. The Role of Ukrainian Women Artists During Political Transformations”. Miejsce, n° 7, 2021, https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.24501611.MCE.2021.7.5

→Ohnieva, Liudmyla (ed.), Alla Horska. The Soul of the Ukrainian Sixties, Kyiv, Smoloskyp, 2015 (in Ukrainian)

→Ohnieva, Liudmyla (ed.), Alla Horska. Biography in the Language of Letters, Donetsk, Smoloskyp Collection, 2013 (in Ukrainian)

Alla Horska. Boryviter, Ukrainian House, Kyiv, 15 March–28 April, 2024

Ukrainian monumentalist painter.

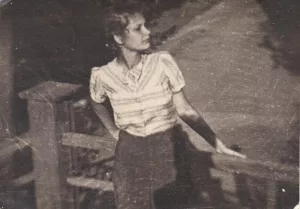

Alla Horska was born in Yalta (Crimea), home city to the Soviet Yalta Film Studio where her father worked. In the 1930s, Joseph Stalin started his violent politics of the Ukrainian Famine (1932–1933) and the subsequent persecution of the intelligentsia known as the Executed Renaissance (1937–1938). In 1932 A. Horska’s family moved to Moscow and then to Kyiv at the end of 1943. There, she studied art at the Taras Shevchenko State Art School (1946–1948) and monumental art at the Kyiv Art Institute (now the National Academy of Visual Arts and Architecture) between 1948 and 1954, followed by carrying out independent research into the history of Ukrainian arts and traditions.

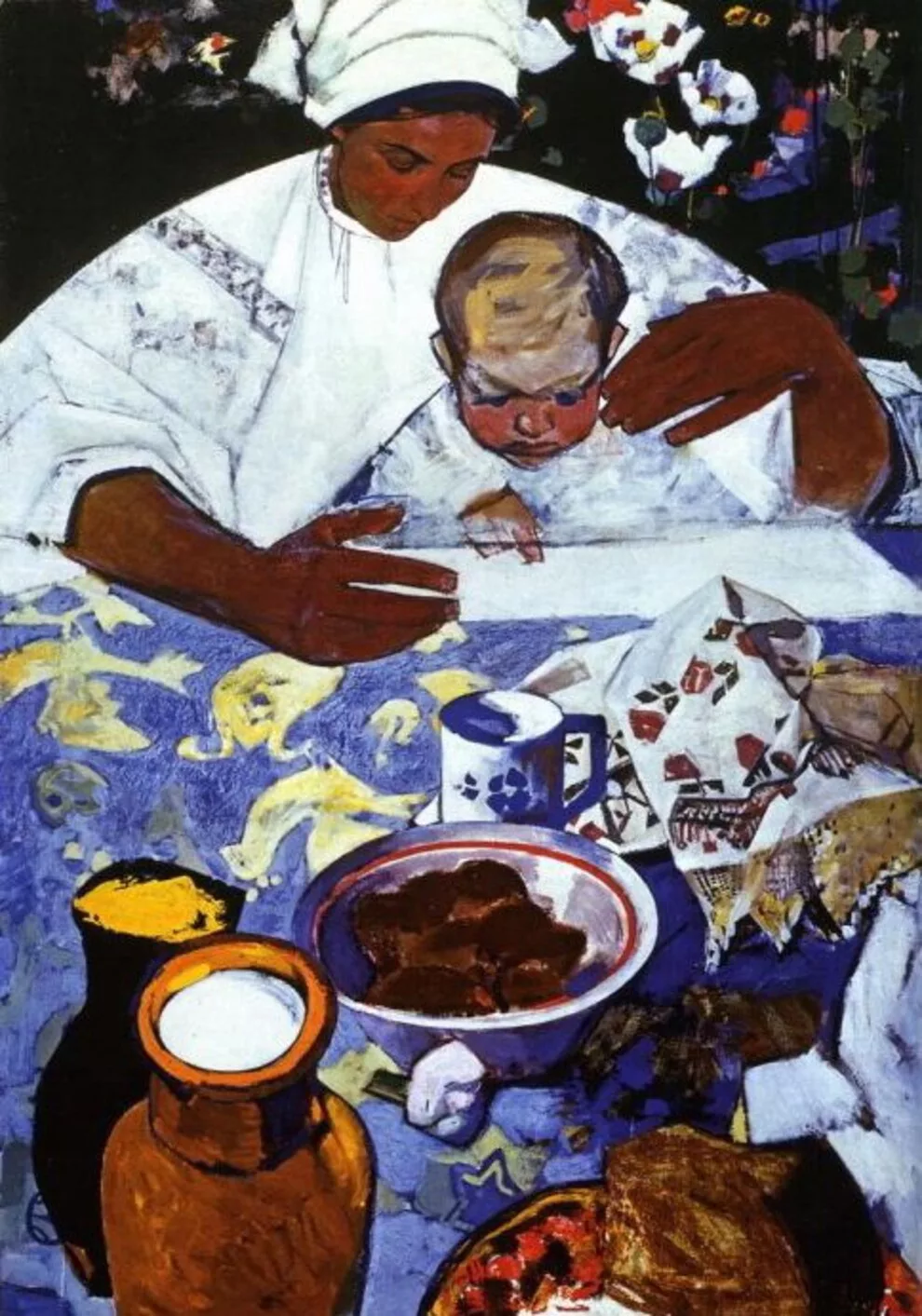

Discovering the energy of local tradition and the past persecution of artists was life-changing for A. Horska. She began to study the avant-garde, especially the works of the Boichukists, an artistic movement in the 1920s which sought to revive mural practices, inspired by monumental traditions and modernism. A. Horska addressed ideas of equal rights and freedom by grounding them in the local environment. She co-organised an artist community called Suchasyk [Contemporary] to exchange ideas with others and became one of the most active figures in the Ukrainian civil rights movement of the 1960s, known as the Sixtiers.

A. Horska’s primary medium was monumental art. By creating such artworks, she spoke of Ukrainian national liberation and culture, for which the Soviet regime oppressed her. Her glass window Shevchenko. Mother (1964), dedicated to the leading national poet Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861), created with Opanas Zalyvakha (1925–2007), Liudmyla Semykina (1924–2021), Halyna Sevruk (1929–1922) and Halyna Zubchenko (1929–2000), was identified as “wrong ideological art” by the authorities. This piece was destroyed, and she and the artists who helped her realise the piece were excluded from the Artists’ Union of the USSR in 1964 for the first time (she re-entered it in 1965).

In the mid-1960s, a new wave of oppression of Ukrainian artists brought her, along with a group of other artists, to Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts: here they found more freedom to work with local context and created monumental panels for schools, restaurants, factories and public spaces. Between 1964 and 1970, A. Horska participated in human rights activities and spoke out against closed trials of dissidents, signing a letter of protest to the leaders of the USSR in April 1968, alongside 139 scientists and cultural figures. She was again expelled from the Artists’ Union.

Her body was found in the forest near Kyiv, its head severed, on 28 November 1970. To this day the circumstances of her death have not been officially disclosed, but for many there is no doubt that the local authorities organised it. A. Horska’s name and her works were censored until 1990.

Most of her outstanding works have been at risk since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. For example, both her mosaic Boryviter (1967), created to decorate a restaurant in Mariupol and depicting a local bird restricted by the strength of the steppe and the Azov wind waves, and the panel The Tree of Life (1967) were destroyed by the Russian airstrike in 2022.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025