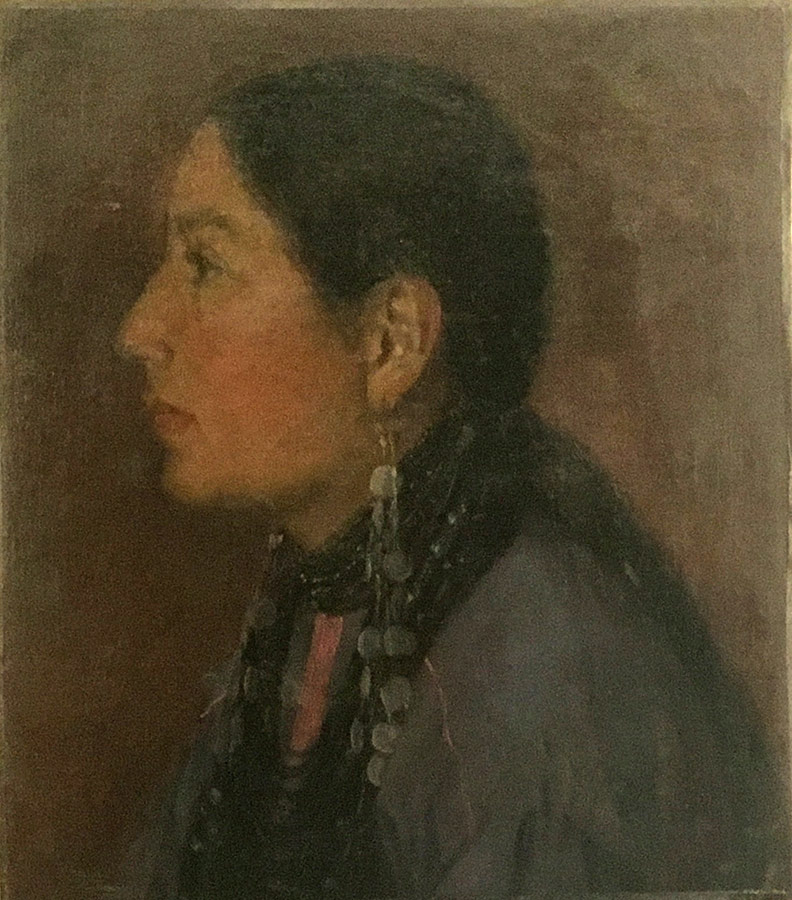

Angel De Cora

Sutton, Elizabeth, Angel De Cora, Karen Thronson, and the Art of Place: How Two Midwestern Women Used Art to Negotiate Migration and Dispossession, Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2020.

→Waggoner, Linda, Fire Light: The Life of Angel De Cora, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

→Gere, Anne Ruggles. “An Art of Survivance: Angel DeCora at Carlisle”, American Indian Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 3/4, 2004, pp. 649-684.

→Hutchinson, Elizabeth, “Modern Native American Art: Angel DeCora’s Transcultural Aesthetics”, The Art Bulletin, vol. 83, no. 4, December 2001, pp. 740-756.

Angel De Cora, Illustrator and Graphic Designer (1871-1919), Forbes Library, Northampton, MA (United States), October 2021

→Hearts of Our People : Native Women Artists, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN (United States), June–August 2019

→Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Exhibit at the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition, Omaha, NE (United States), June–November 1898

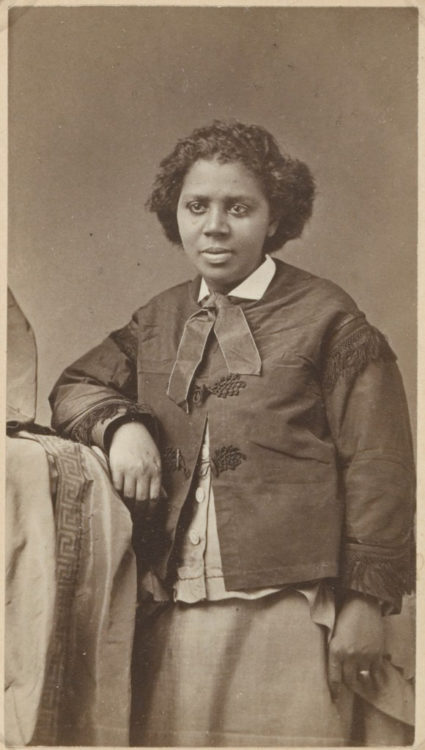

Native American painter, designer and illustrator.

A member of the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribe, Hinųk Mąxiwi Kerenąka (which means “Woman Returning Back to the Sky”), also known as Angel De Cora, was the granddaughter of Chief Little Decora and was a part of the Thunder clan. A. De Cora was born and spent her early years on the Winnebago Reservation in Nebraska.

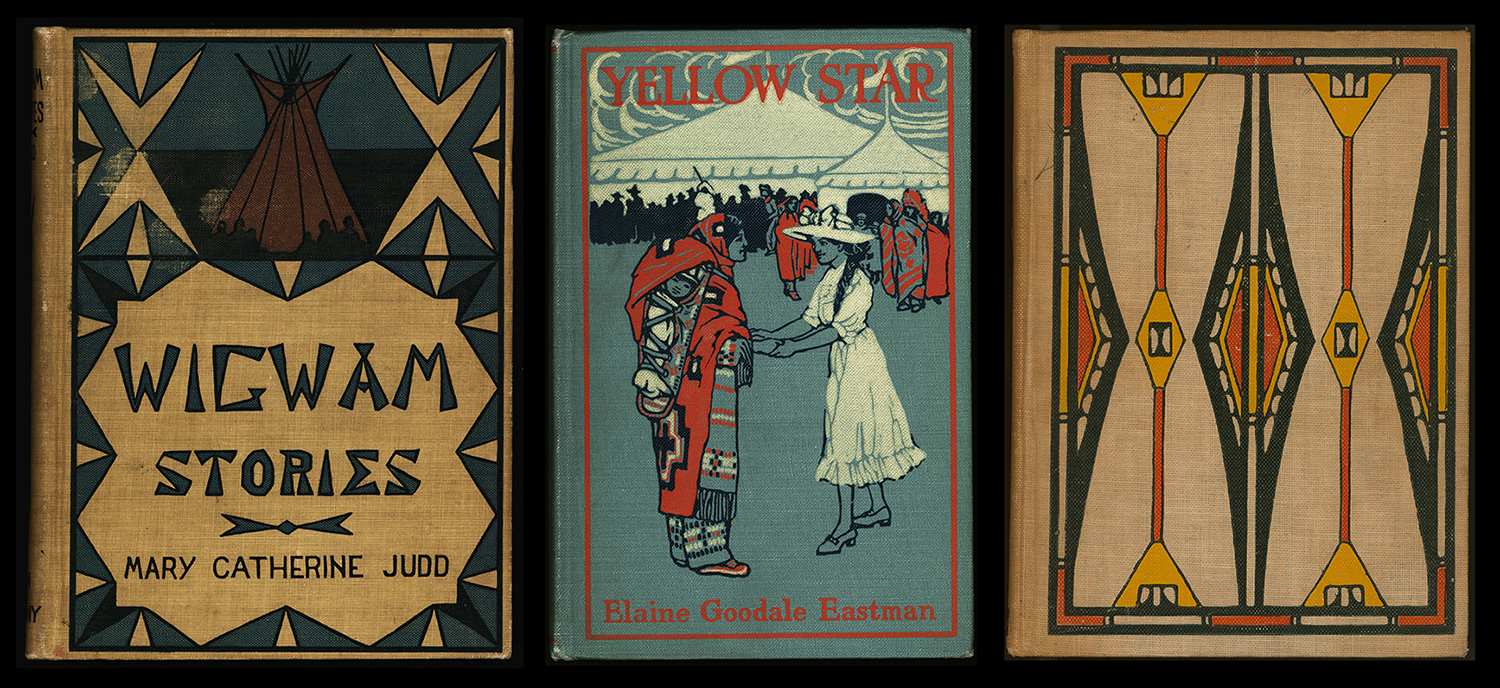

As an Native child in the United States during the settler efforts of assimilation, A. De Cora, along with six other children from the Winnebago Reservation, was kidnapped in 1883 and sent to the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute boarding school in Hampton, Virginia. She was finally able to visit home five years later. A. De Cora then graduated from Hampton in 1891. She continued her Western education at Burnham Classical School for Girls, Smith College, Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry, and Cowles Art School, before studying at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. During her education she studied with numerous teachers who impacted her appreciation for painting and illustration. During this period, they, like many other non-Native people, were fascinated with the “primitive” and her work and identity elated non-Native audiences. Because of this fascination, she saw how non-Native artists depicted Native Americans and how depictions of the American West included generic symbols of Native American identity. A. De Cora instead depicted tribally specific design elements in her work because other Native people would be able to recognise her consideration in making her depictions as accurate as she could.

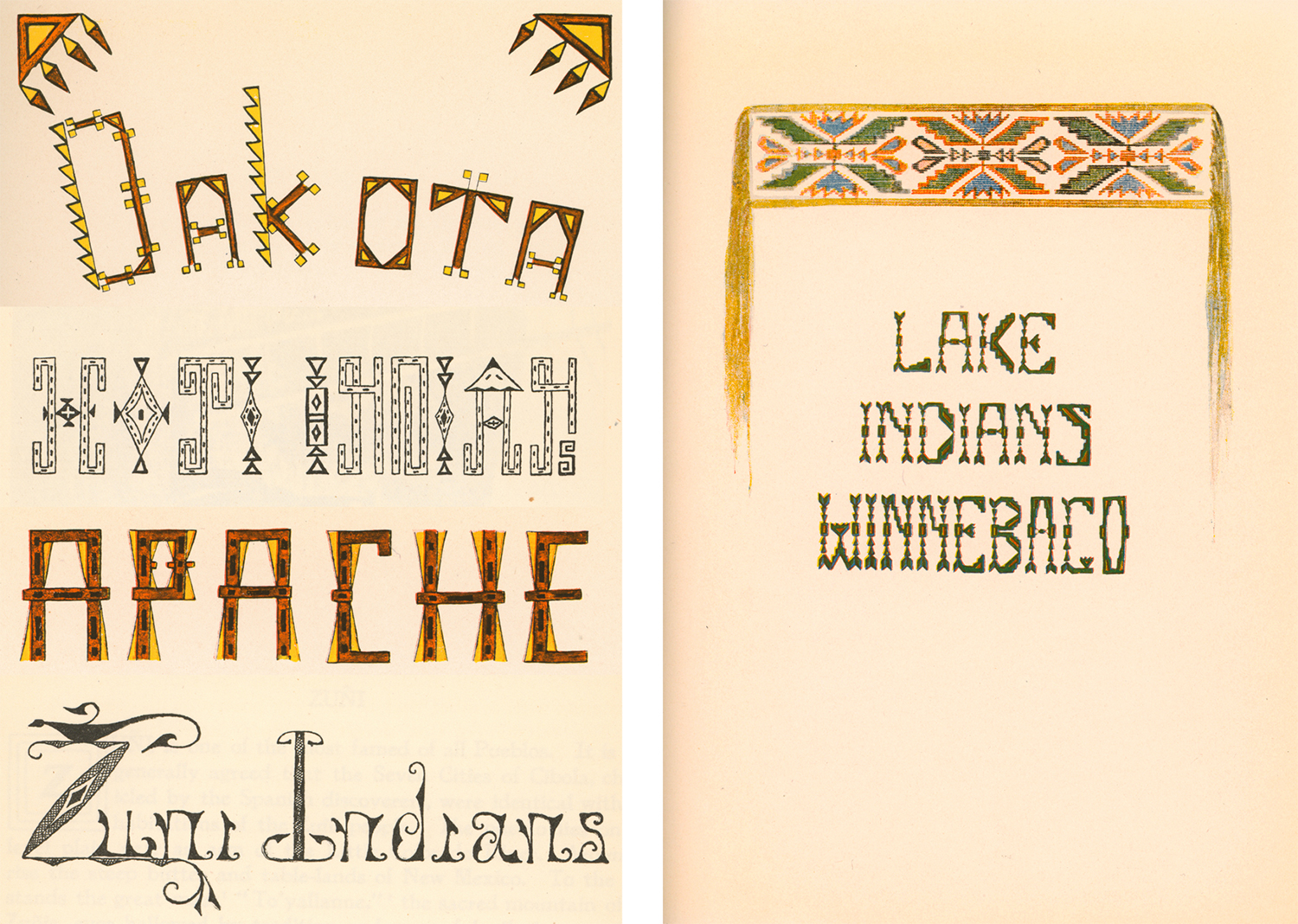

A. De Cora then taught at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from 1906 to 1915. While there, she encouraged students to research the traditional Native designs of their specific tribal heritage and to incorporate them into their artworks. This effort to continue to preserve and recreate the designs of their Native Nations was a decolonial act during this devastating period in Native American history.

She reflected on this separation of American and Native American arts in a 1911 Carlisle newspaper, Red Man: “There is no doubt that the young Indian has a talent for the pictorial art, and the Indian’s artistic conception is well worth recognition, and the school-trained Indians of Carlisle are developing it into possible use that it may become his contribution to American Art.” By encouraging young Native artists to continue practising Native art forms, she advocated for including Native art in institutional understandings of “American” art production.

After she left Carlisle, A. De Cora made illustrations for various projects, including for the Society of American Indians (the first Native-led Native rights organisation in the United States), where she held an officer position and continued to illustrate for their quarterly magazine. In 1919 she died from pneumonia brought on by the influenza pandemic.

As one of the most widely known Native artists of her time, A. De Cora used her position to advocate for Native American artists, the value of Native arts, and their contribution to American art. She frequently wore Plains-style traditional regalia during her speeches and public engagements to demonstrate her authenticity as a modern Native American woman and to disrupt the settler art and academic world in the United States that considered Native Americans to be a thing of the past. While she faced the trauma of being a student and educator in North America’s horrendous boarding school history, she used her education and position to encourage young Native students to continue practising the elements of their Native identity that could not be disrupted in the boarding school.

A biography produced as part of “The Origin of Others. Rewriting Art History in the Americas, 19th Century – Today” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023

« An Exploration of Angel DeCora’s Design and Lettering Work », Letterform Archive, March 8, 2022

« An Exploration of Angel DeCora’s Design and Lettering Work », Letterform Archive, March 8, 2022