Research

Seba Calfuqueo, A imagen y semejanza [To her image and likeness], 2018 (detail), installation, photograph (110 x 65 cm), 2 photographs (2 x 4 cm), shelf and magnifier, register by Diego Argote © Courtesy Seba Calfuqueo

This article’s title is taken from the title of a piece by Rosana Paulino (b. 1967), an Afro-Brazilian artist who has become a reference for new generations of artists struggling to transform the politics of artistic representation. In writing about the exhibition 34 Panorama del Arte Brasileño (Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, 2015), which presented carved stone sculptures, Brazil’s oldest artworks, alongside the work of six non-Indigenous artists invited to address the abstract art Indigenous past, she asked why no work by contemporary Indigenous artists was included.1 I’ve altered her original phrase – “representation without participation” – swapping “without” for “and” to underline the necessity and urgency of transforming this situation. There are more than five hundred groups of Indigenous peoples among the Latin American population, but their work is barely starting to become visible in the continent’s predominantly white art landscape. How can an inclusive art historical narrative be produced? This article offers an evaluation of the representation and participation of artists linked to the continent’s first peoples in contemporary Latin American art. It explores both the work of non-indigenous artists in relation to the cosmologies of first peoples, as well as the active participation of indigenous artists. It touches on not only the work of women but also non-binary artists.

In order to produce a representation with participation it is necessary to form alliances, open doors and contribute to strategies to empower Indigenous artists and cultures. While the process of participation by Afro-descendant artists started at the end of the twentieth century and is now being consolidated,2 in the case of original peoples, their presence in contemporary art is more recent, framed by the situation following the outbreak of Covid-19.

It is not that there have been no reappraisals or attempts to find the ways in which pre-Hispanic imaginary has been incorporated into Latin American art. The indigenist tradition has found expression since the founding of Latin American nation states in the nineteenth century. The 1920s and 1930s saw two important movements, Muralism in Mexico and Indigenismo in Peru. There has also been an abstract indigenist current, exemplified by artists such as Elena Izcue (1889-1970) in Peru and Rosa Acle (1919-1990) in Uruguay.

Claudia Andujar, Xirixana Xaxanapi thëri mistura mingau de banana em cocho suspenso, capaz de armazenar até 200 litros de alimento para as festas, Catrimani [Xirixana Xaxanapi thëri mixes banana porridge in a suspended trough capable of storing up to 200 liters of food for ceremonies, Catrimani], from A casa [House] series, 1974, gelatin and silver analog enlargement on Ilford Multigrade Classic fibre based matte paper, with selenium toning, enlarged by Elisabete Savioli, São Paulo, Courtesy Galeria Vermelho © Claudia Andujar

Since the 1970s the ethical, aesthetic and political photos of Claudia Andujar (b. 1931), a Swiss-born Brazilian artist who lives in São Paulo, has familiarised the public with Yanomami Indigenous communities.3 By publicly exposing the appropriation of their lands, pro-mining government policies and the clearing of the Amazon, C. Andujar has played an exemplary role as an activist in the struggle to save Yanomami lives and culture. Nevertheless, her photos leave no agency to the Yanomami community to decide how their story will be told and express their sensibilities.

The work of the Brazilian artist Anna Bella Geiger (b. 1933) also takes up the question of tribal peoples. Her performance photos mock the exoticisation generated by tourism when it erases specific identities, cultures and problematics.

Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu Menstrual at La Moneda [Menstrual Quipu at the Moneda], 2006, street performance in front of the government palace, Santiago, photo: Rodrigo Chodil © Courtesy Cecilia Vicuña

Cecilia Vicuña, Kon Kon, 2006, HD video, 53 min. 55 s. , color, sound, Spanish with English subtitles, photo: Pilar Polanco © Courtesy Cecilia Vicuña

Cecilia Vicuña, Cantos del Agua [Songs of the water], 2015, a sound-weaving improvisation performance, Galería Patricia Ready in Chile, January, 2015, video stills by Antonio Pozo © Courtesy Cecilia Vicuña

With her quipus and singing, the Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña (b. 1948) evokes, introduces and references an abstract, general idea of Indigenous presence. Although she had a genealogical DNA test done to prove her Indigenous origins, her work simply references a generalised identity, unsituated in the voice of today’s multiple Indigenous problematics.

Nelbia Romero, Sal-si-puedes [Get out if you can], 1983, documentation of performance, colour photograph, courtesy of Teresita Romero Cabrera © Nelbia Romero

Nelbia Romero, Sal-si-puedes [Get out if you can], 1983, documentation of performance, colour photograph, courtesy of Teresita Romero Cabrera © Nelbia Romero

The work of the Uruguayan artist Nelbia Romero (1938-2015) also denounces the genocide of Indigenous peoples. In Sal-si-puedes [Escape-if-you-can, 1983] she exposed the massacre of the Charrúa people in 1831, drawing a direct line between the violence of Uruguay’s founding as a country in the nineteenth century and the military dictatorship of 1973-1985.4

In the context of the fifth centenary of the conquest of Latin America, Indigenous imaginaries were powerfully reactivated. This interest arose in an international context marked by exhibitions such as the renowned Magiciens de la terre held in 1989 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Maruch Sántiz Gómez, Es malo sonar las semillas del chile [It is bad to sound the chili sedes] from the series Creencias de nuestros antepasados [Beliefs of our ancestors], 1994, silver on gelatin and text in Tzotzil, 22 5/8 x 18 3/4 in, 57.5 x 47.5 cm, courtesy OMR © Maruch Sántiz Gómez

Maruch Sántiz Gómez, No mencionar el nombre de la hoja de bejao al envolver tamales [Do not mention the name of the bejao leaf when wrapping tamales] from the series Creencias de nuestros antepasados [Beliefs of our ancestors], 1994, silver, gelatin and text, 18 3/4 x 22 5/8 in, 47.5 x 57.5 cm, courtesy OMR © Maruch Sántiz Gómez

Maruch Sántiz Gómez, Para evitar que caigan granizos grandes [To prevent large hailstones from falling] from the series Creencias de nuestros antepasados [Beliefs of our ancestors], 1994, silver gelatin and text in Tzotzil, 22 5/8 x 18 3/4 in, 57.5 x 47.5 cm, courtesy OMR © Maruch Sántiz Gómez

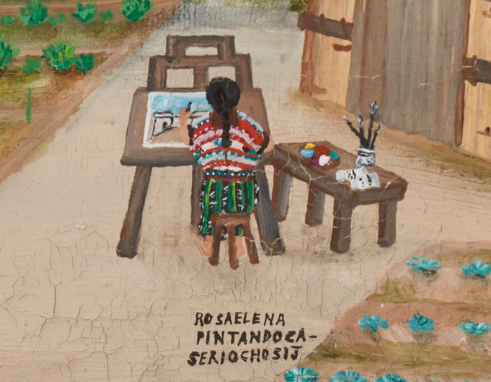

Maruch Sántiz Gómez (b. 1975) has been producing remarkable work since the 1990s. A member of the Tzotzil community in Chiapas, Mexico, she had no formal art education and spoke no Spanish. Later, during a workshop in her community, she learned photographic and darkroom techniques from John Taboa and María Maronel. In 1991 she began making Creencias de nuestros antepasados [Beliefs of our ancestors], a collection of traditional sayings that concentrate and seek to preserve her community’s wisdom. Each saying is accompanied by a photo depicting seeds, leaves, animals and so on. In the way she connects images and texts, M. Sántiz Gómez produces a sophisticated poetics. Although she identifies as an artist and has gallery representation and collectors, both private and institutional (such as the Daros Latinamerica Collection and the Museo Reina Sofía), have acquired her production, changing fashions have damped the interest in her work shown in previous decades. This example serves as a crucial warning about the way those of us who have the power to intervene in the art world operate.

Portrait of Juana Marta Rodas and Julia Isídrez

Portrait of Juana Marta Rodas and Julia Isídrez

Portrait of Julia Isídrez

The Indigenous presence has been and still is powerfully visible in Paraguay, represented by theoretical work and the acquisitions practices of Ticio Escobar (b. 1947) and Ricardo Migliorisi (1948-2019), based at the Museo del Barro in the city of Asunción. This museum’s holdings include a broad representation of contemporary Indigenous cultures, along with colonial-era and contemporary artworks, resulting in a unique juxtaposition. It celebrates beauty rather than exoticism, providing a reading of Indigenous art that T. Escobar put forward in his extraordinary books La belleza de los otros. El arte indígena del Paraguay [The Beauty of Others. Indigenous Art in Paraguay,1993] and The Curse of Nemur: In Search of the Art, Myth and Ritual of the Ishir.5 With the exception of the Museo del Barro, Indigenous communities are not systematically represented in any contemporary art showcase.

By bringing together disparate artworks and time periods, T. Escobar also seeks to identify and more widely promote craftspeople who explore novel approaches. For instance, the innovative use of clay and fire by Juana Marta Rodas (1925-2013) and her daughter Julia Isídrez (b. 1967) have transformed traditional ceramics. They appropriated the industrial furnaces introduced by the International Development Bank in the 1980s. It is interesting to note that when these kilns were first built, potters turned their backs on them as useless for the small pieces they were then making. Years later the furnaces were appropriated and reactivated to make much bigger ceramics and new forms echoing Guarani culture, with its funerary urns and vessels to hold water and food. This new approach is infused with references to an imaginary, mestizo animality. Form no longer follow functionality in these oversized works. While both artists were invited to Documenta 13 in Kassel in 2012, they have not found a home in the contemporary art world. Curators showed an interest in them during a certain period but then they faded out of fashion.

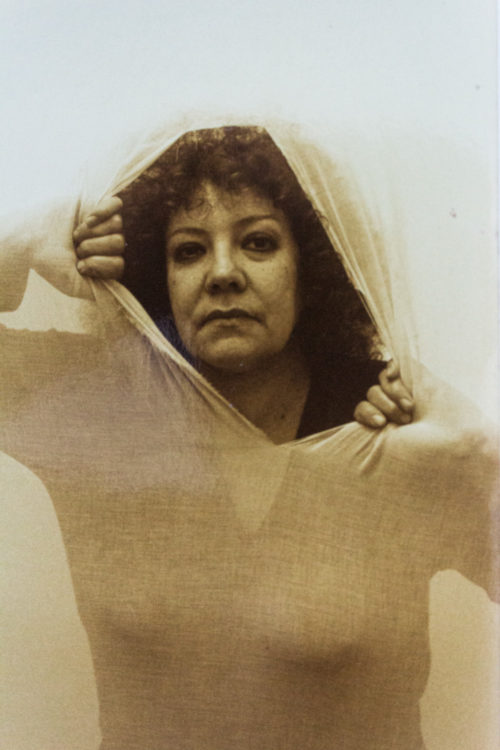

Seba Calfuqueo, A imagen y semejanza [To her image and likeness] (detail), 2018, installation, photograph, 110 x 65 cm, 2 photographs, 2 x 4 cm, shelf and magnifier, register by Diego Argote © Courtesy Seba Calfuqueo

Seba Calfuqueo, A imagen y semejanza [To her image and likeness] (detail), 2018, installation, photograph (110 x 65 cm), 2 photographs (2 x 4 cm), shelf and magnifier, register by Diego Argote © Courtesy Seba Calfuqueo

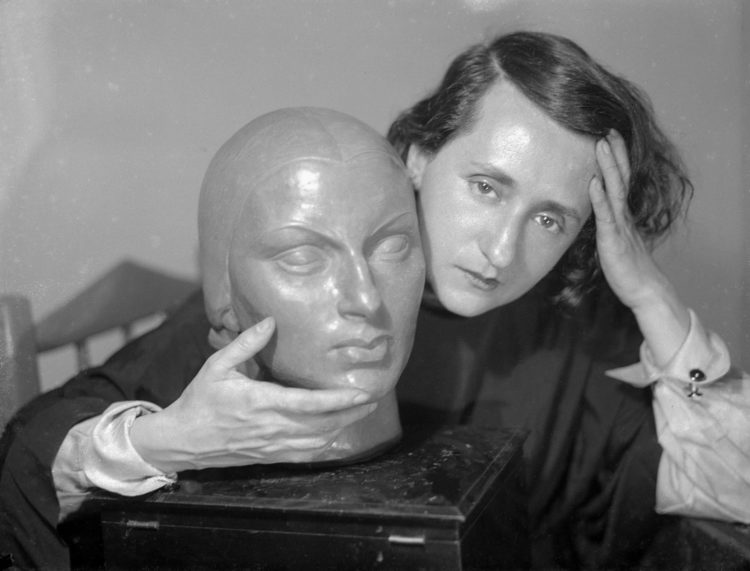

In Chile, Seba Calfuqueo (b. 1991), a non-binary artist of Mapuche origin, makes installations and videos about subjects such as migration, deterritorialisation and the construction of the links between eroticism, pornography and photography in the twentieth century. In one of their installations they juxtapose an erotic photo of a nude European female, a picture of a Yahgan Indigenous woman taken in 1882-1883, and a self-portrait where they reproduce the position of the women in both photos. S. Calfuqueo contrasts the European vision of sexuality with their own, which is non-binary and non-essentialist.

Returning to the Yanomami nation, which extends along the Brazilian-Venezuelan border, we should also note a recent transformation in which new collection policies have brought about increased visibility for artists such as Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe (b. 1971), from the Yanomami community of Pori Pori, in Venezuela, who makes drawings on natural fibres. He first interacted with contemporary art in the early 1990s when he held a workshop on making paper by hand with the Mexican artist Laura Anderson Barbata (b. 1958). In 2020 the Malba contemporary art museum in Buenos Aires acquired a series of his work. It was exhibited at the New York Armory Show (at the Marlborough gallery’s stand), along with art by L. Anderson Barbata.

Brazil has also witnessed significant changes regarding the representation of Indigenous peoples in contemporary art. Although the 2014 show Histórias Mestiças at the Instituto Tomie Ohtake in São Paulo included Yanomami drawings that were then still anonymous (from the Claudia Andújar collection), today Indigenous artists and curators speak for themselves.

Nevertheless, recent conflicts demonstrate that the conversations are not simple. In 2019 Sandra Benites, of the Guaraní Ñandeva people, became the first Indigenous curator at MASP, São Paulo’s museum of contemporary art. The significance of this event was highlighted by an article in The New York Times, which reported her intention to include women artists of “various ethnicities and disciplines, like a Guajajara performance artist, a Karajá photographer, a Huni Kuin painter, and Guarani and Maxacali audiovisual artists”, and quoted her expressing aim to ensure women artists as “protagonists of their own voices.”6 In May 2022, while preparing the exhibition Historias Indígenas, she and the show’s adjunct curator Clarissa Diniz resigned. In an open letter they revealed that the museum had eliminated photos from the Movimiento Sin Tierra, a landless peasant movement, with the pretext that these photos had not been included in time, when the proposal for the exhibition was submitted to museum authorities. The two women disputed this argument, saying that they had never been given any timeline so that this decision was a concealed form of censorship.7 Museums may seek to be more inclusive, but have they found how to carry out a real dialogue?

In the context of pandemic turbulence, the curators of the Bienal de São Paulo decided that the term “diversity” (women, Afro-descendant and Indigenous artists) would be the key for its 34th edition in 2021. They invited Jaider Esbell (1979-2021), a Macuxi artist and activist, who in turn suggested bringing in many other artists from his community. In an interview he explained that taking part in an exhibition in the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo was not so easy, that he had to go up against the biennial’s organisers who were prepared to show his work but not that of others in his community.8 The Paraguayan museum director T. Escobar had a pessimistic take on this biennial. He understood that the focus on “diversity” was simply a turn in the curatorial market.9 Obviously there is a big symbolic and political difference between speaking in the name of, speaking from a position of empathy arising from engagement in the conversation, and speaking from the positions of the expelled and subalterns.

Curator Pablo José Ramírez (1982-) was born in Guatemala, and works between there and London, where he is Adjunct Curator of First Nations and Indigenous Art at Tate Modern. He studies the relationship between pre-Hispanic, pre-colonial cultural expressions and contemporary art. Starting from the concept of culturas planetarias (planetary cultures, not global, a term associated with finance capitalism), he argues for post-identitarian discourses that are permeable and open to new connections. He formulated these ideas while in Europe, where his own mestizo experience is subjected to those conceptual and discursive matrixes. He identifies the subaltern status he left behind with his transformation into a global mestizo subject. Living in London affords him an epistemic distancing that seeks connections that go beyond identities. Can people who still live in their original contexts produce such a distancing? Is that an option for people who live in the Paraguayan Chaco, the Amazon rainforests or the Mapuche Nation, fighting to keep their territory and culture, people for whom cosmopolitanism means nothing but ever-expanding capitalist plunder?

When Cecilia Fajardo-Hill and I curated Radical Women: Latin America, 1960-1985 in 2017, there was little presence of women artists linked to Indigenous world outlooks, since so few had participated in the art scene. People at the margins of the art world are occasionally invited to take part in group shows, biennials and publications, and then forgotten. They are represented, but don’t participate, to once again cite R. Paulino. It seems that we are on the cusp of a change in which women and non-binary Indigenous artists can finally and superbly expand cultural dialogues.

Andrea Giunta is Principal Researcher at CONICET, Argentina. She is also a professor of Latin American, modern and contemporary art at the Universidad de Buenos Aires, where she obtained her doctorate. She was co-curator of the exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985 (Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Brooklyn Museum, New York; and the Pinacoteca de São Paulo, 2017–2018). She was also chief curator of the Mercosur Biennial 12 in Porto Alegre, Feminine(s): visualities, actions, affections in 2020 and the exhibition Pensar Todo De Nuevo (Rethink Everything) (Rolf Art, Buenos Aires, 2020, and Les Rencontres d’Arles, 2021). She is the author of The Political Body: Stories on Art, Feminism, and Emancipation in Latin America, published by University of California Press (2023).

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Andrea Giunta, "Representation and Participation: Indigenous Latin American artists in the Transition between Two Centuries." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/representation-et-participation-artistes-indigenes-latino-americaines-dun-siecle-a-lautre/. Accessed 25 April 2024