Anna Atkins

Larry J. Schaaf, Joshua Chuang (eds.), Sun Gardens: Cyanotypes by Anna Atkins, New York, New York Public Library, Prestel, 2018

→Carol Armstrong, Scenes in a Library: Reading the Photograph in the Book, 1843-1875, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press, 1998

→Larry J. Schaaf, Sun Gardens: Victorian Photograms by Anna Atkins, New York, Aperture, 1985

Blue Prints: the Pioneering Photographs of Anna Atkins, the New York Public Library, New York, October 19, 2018 – February17, 2019.

→Sun Gardens: An Exhibition of Victorian Photograms by Anna Atkins, St. Andrews, Crawford Centre for the Arts, April – May 1988.

British photographer.

Anna Atkins was a botanist and a pioneer in the history of photography and illustrated publications. Doubly privileged by birth and social background, she was the only child of eminent chemist, mineralogist and zoologist John George Children, who provided her with a thorough education and introduced her to the scientific circles of the time. Her talent as a draughtswoman led her to illustrate her father’s 1823 English translation of French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s Genera of Shells. Both her marriage in 1825 to John Pelly Atkins, a wealthy merchant and landowner who was also interested in science, and the fact that they had no children, were also circumstances that helped A. Atkins remain invested in botany – one of the rare scientific fields relatively open to women of the British polite society. In the mid-1830s she started to put together a herbarium (after adding to it for thirty years, Atkins donated it to the British Museum in 1865). In 1839 she was elected a member of the London Botanical Society, where her father then served as vice-president. He was also a member of the Royal Society, where William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) caused a sensation that same year with his invention of paper photography. W. H. F. Talbot and J. G. Children would maintain scientific exchanges on the subject, as they had in the case of many others throughout the years. This is how A. Atkins, who herself had direct contact with the inventor, became one of the first women practitioners of paper photography.

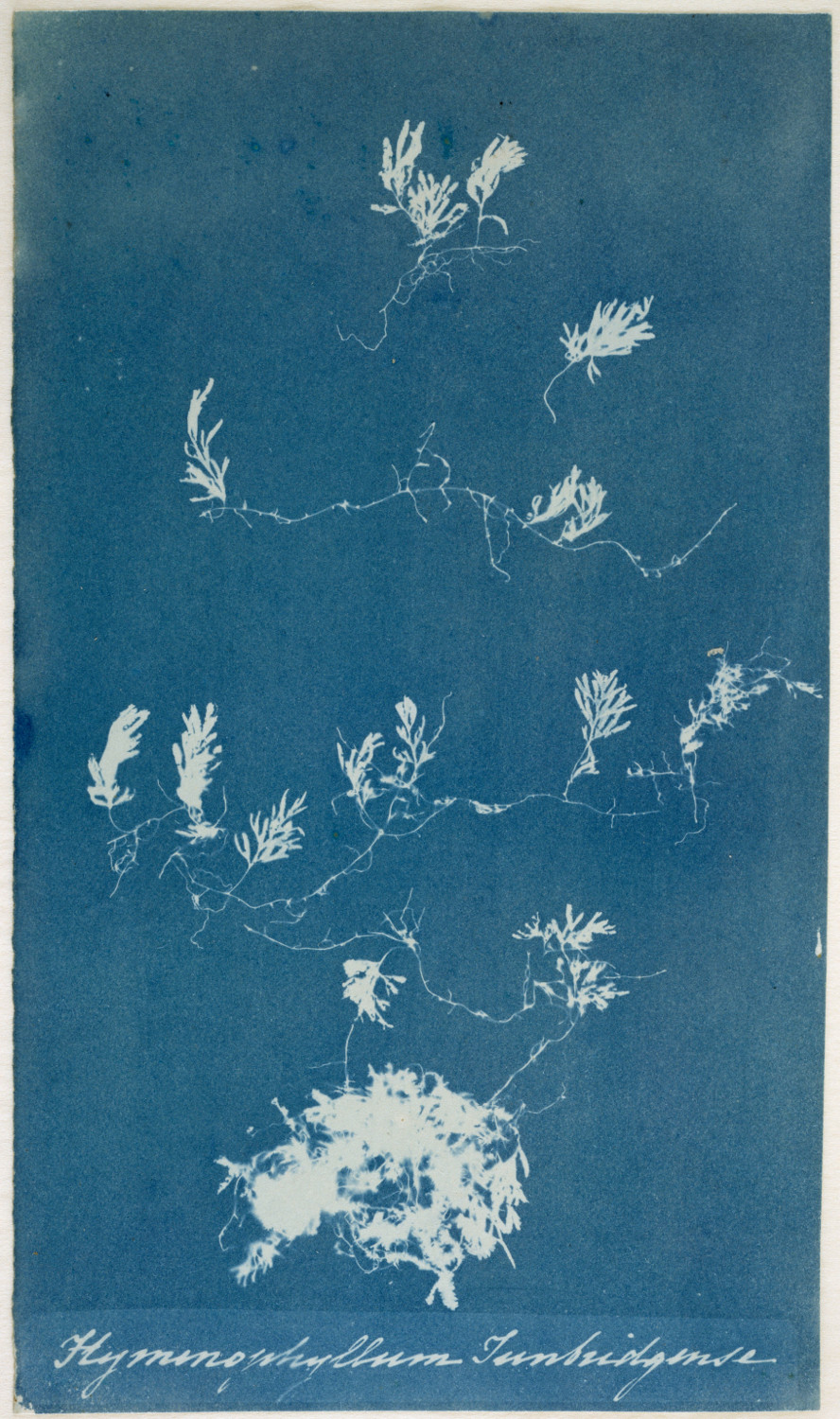

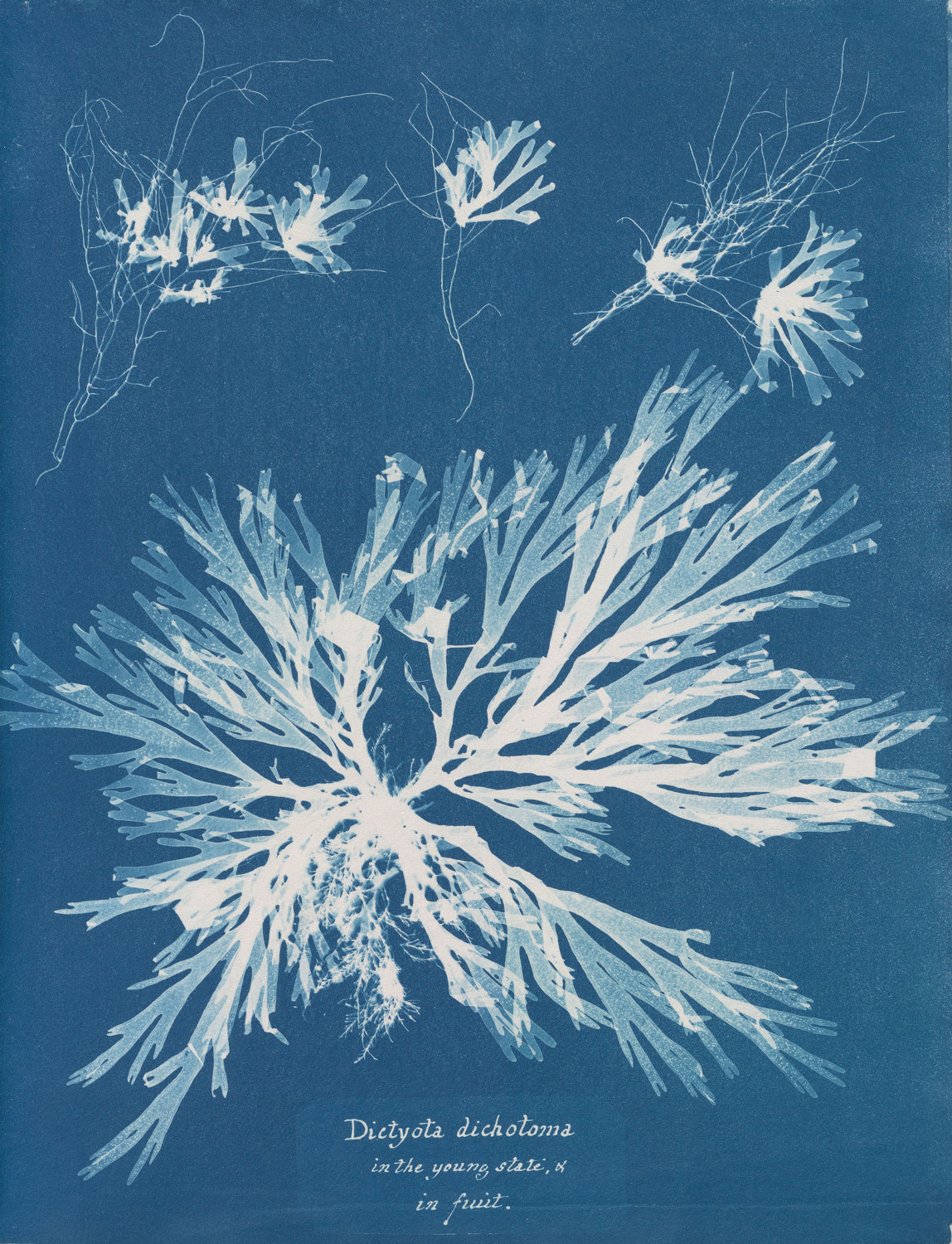

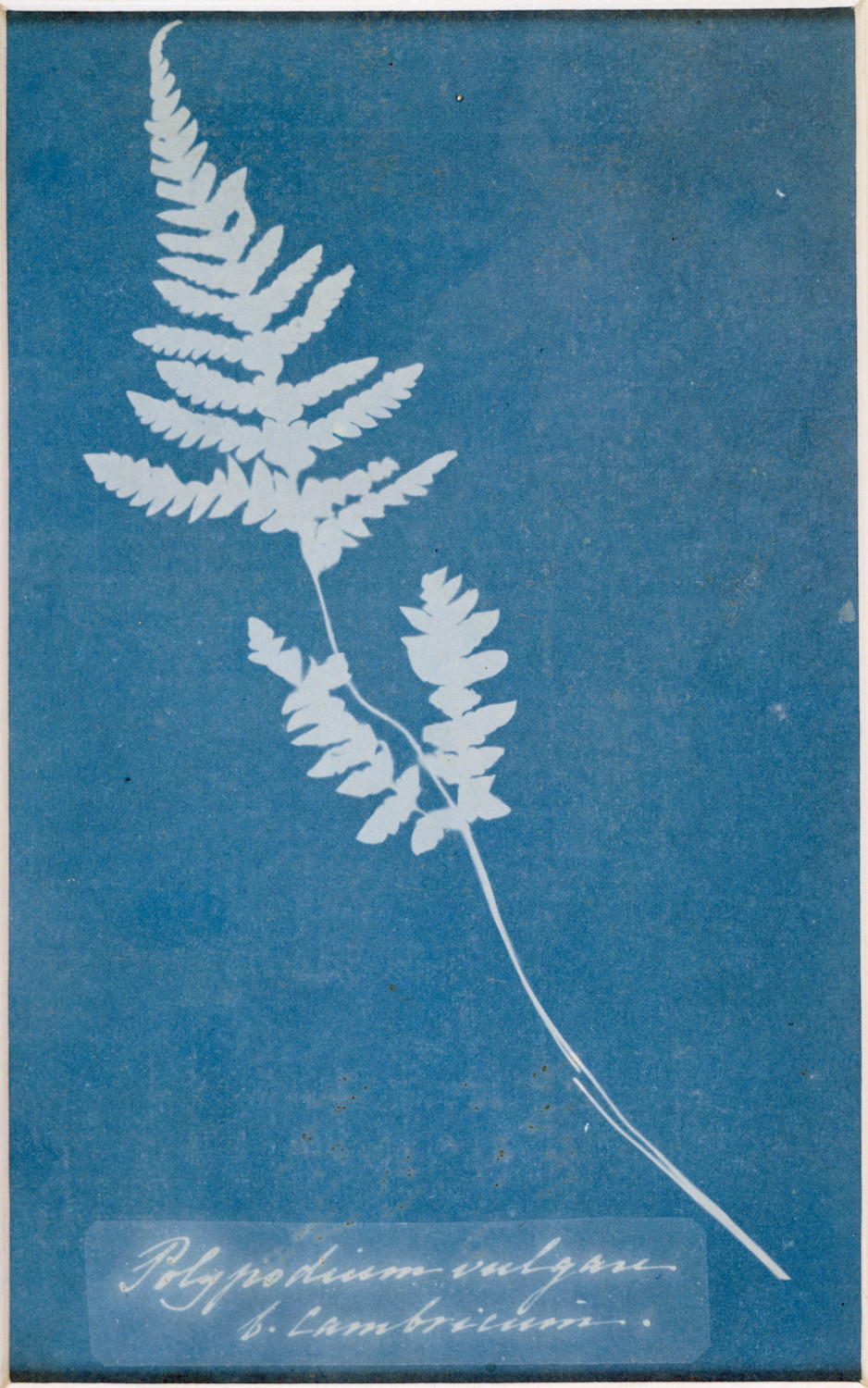

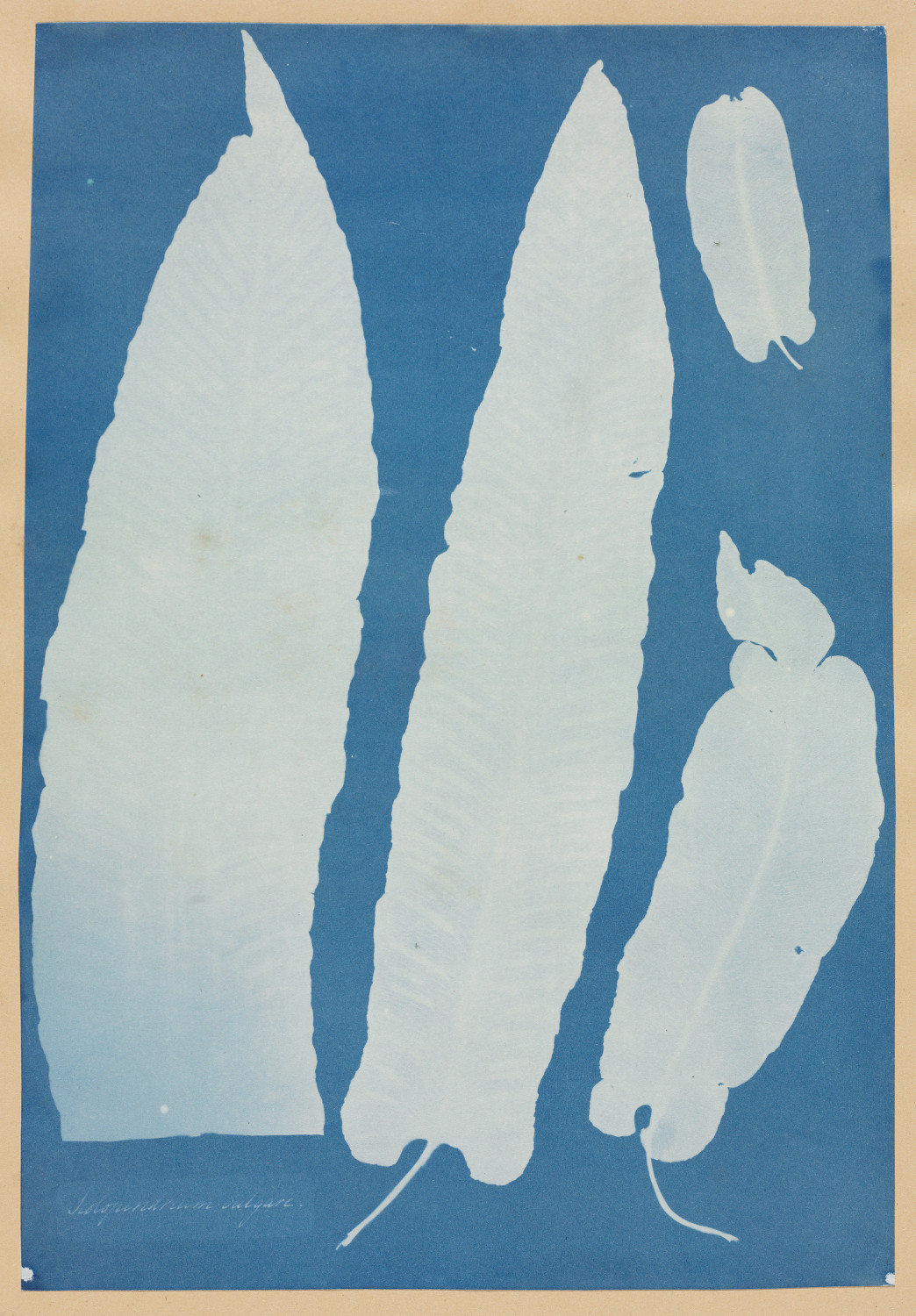

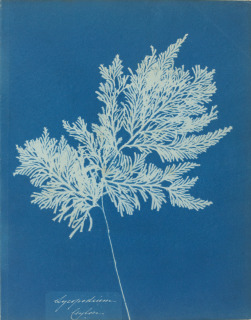

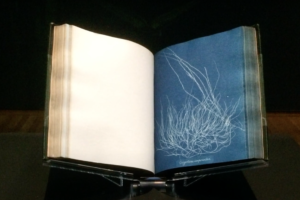

From then on, she would move away from drawing and use photography to document her collection of algae, driven by the promise of saving time and, more importantly, increased precision in her scientific descriptions. While she did own a camera as from the autumn 1841, she favoured the photogram technique instead for this specific purpose. Using this primitive method of cameraless photography developed by W. H. F. Talbot, who called it “photogenic drawing”, she was able to produce negative images of her specimens by exposing them to the sun in direct contact with sensitised paper sheets. Unlike Talbot, who used silver salts, A. Atkins achieved her impressions using ferric salts, resulting in “Sir John Herschel’s beautiful process of cyanotype”, as she called it – a process that had just been invented in 1842 by this renowned astronomer and physician, also a close neighbour and family friend.

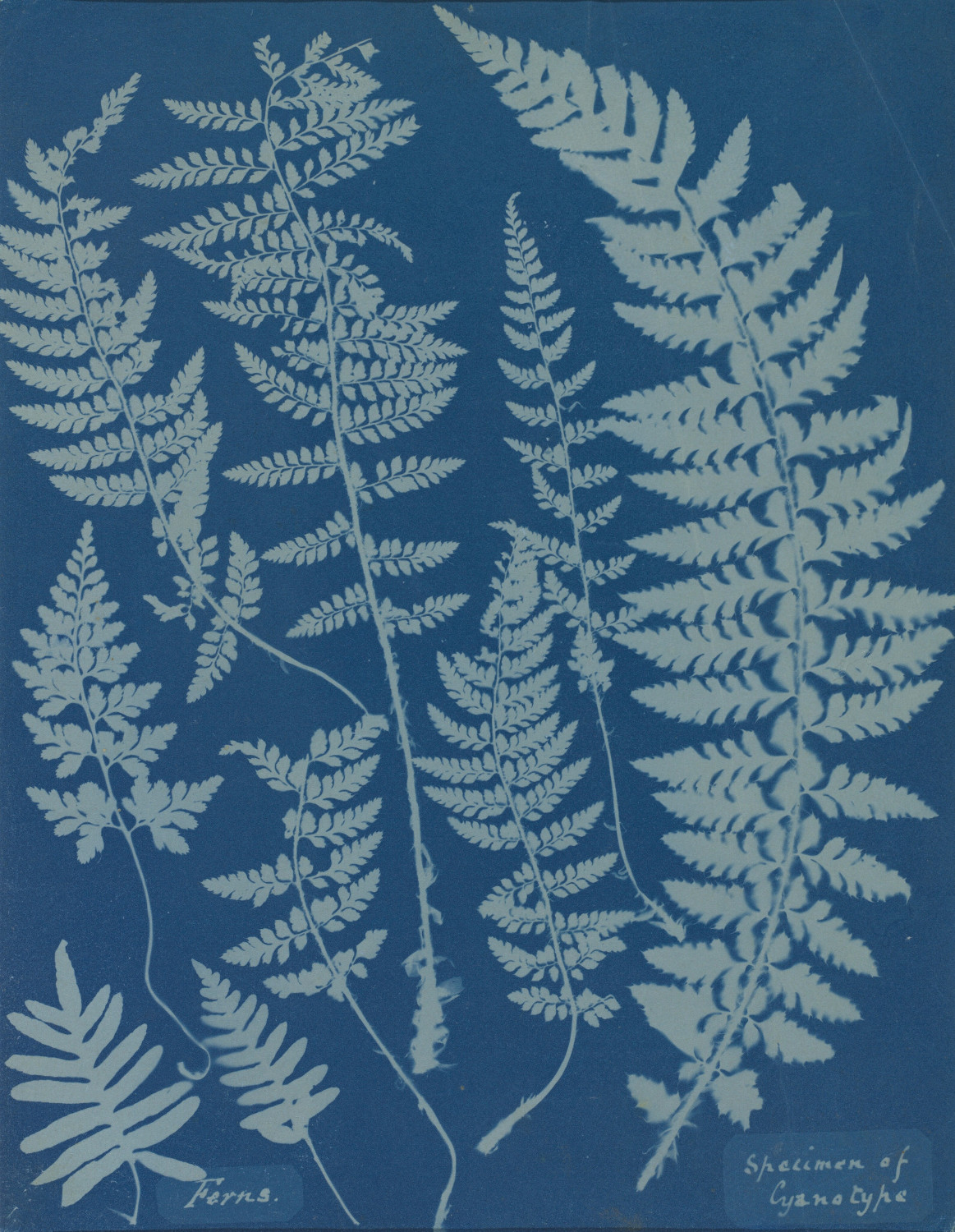

Between October 1843 and November 1853 A. Atkins self-published and privately released Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, a three-volume book with 389 captioned plates and fourteen pages of text. The issue date of the first of the twelve fascicules makes it not only one of the earliest applications of the new invention to science but also the first photographically illustrated book (the same technique was also used to reproduce the text). Around the time she was completing it, she started a photographic collaboration with Anne Dixon (1799-1864), née Austen (a distant cousin of novelist Jane Austen). This fruitful partnership would last at least until 1861. While the complicity between the two childhood friends can be felt in the late experimentation with non-vegetal motifs such as feathers and lace, one can find in the photograms of ferns and flowers the same creative balance that the algae had earlier inspired, between botanical accuracy, expressivity and formal harmony.

The work of A. Atkins has been studied and recognised for its pioneering qualities since the mid-1980s. A century earlier Scottish historian and bibliophile William Lang was instrumental in preventing her name from falling into oblivion: in 1889 he reviewed his incorrect interpretation of the initials “A. A.”, with which Atkins had signed her introduction to British Algae, and presented to the Philosophical Society of Glasgow the photographer whom he had at first mistakenly thought to be an “anonymous amateur”.

Publication made in partnership with musée d’Orsay.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

Anna Atkins: Botanical Illustration and Photographic Innovation | Geoffrey Batchen and Lena Fritsch

Anna Atkins: Botanical Illustration and Photographic Innovation | Geoffrey Batchen and Lena Fritsch  Anna Atkins' special photo book | Hans Roseboom, Rijks Museum

Anna Atkins' special photo book | Hans Roseboom, Rijks Museum