Barbara Hepworth

Bowness Alan, The Complete Sculpture of Barbara Hepworth, 1960–69, London, Lund Humphries, 1971

→Wilkinson Allan G., The Drawing of Barbara Hepworth, London, Lund Humphries, 2015

→Bowness Sophie (ed.), Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations, London, Tate Publishing, 2015

Barbara Hepworth, Wakefield City Art Gallery and Bankfield Museum, Halifax, 1944

→Barbara Hepworth, musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy, 12 January–27 March 2006

→Barbara Hepworth, Sculpture for a Modern World, Tate Britain, London, 24 June–25 October 2015

British sculptor and draughtswoman.

While she is often presented as Henry Moore’s female alter ego, Barbara Hepworth did not enjoy the same renown. Their parallel careers began at the Leeds School of Arts, where the young girl from a humble background began studying sculpture, which she later continued from 1921 to 1924 at the Royal College of Art in London, which still taught according to 19th-century canons. From 1924 to 1927, she lived in Florence, where she became interested in Etruscan and Romanesque sculpture rather than Renaissance art, before joining her first husband, the sculptor John Skeaping, at the British School in Rome. It was in the Italian capital that she learned direct carving, a technique she and H. Moore would come to specialise in. In an article from The Studio (1932), she explained that “the sculptor carves because he must” and declared her fondness for the resistance of the hard material. She renewed her approach through the use of a diversity of materials and colours throughout her career: stone in all its forms (marble, various shades of alabaster) and warm-toned exotic wood essences (teak, ebony, sycamore, mahogany, sequoia, Burmese wood, rosewood). Her earliest sculptures were animal-themed, providing her with a minimalist subject matter that freed her from the restrictions of the figurative tradition and enabled her to take her work to the limits of abstraction: Doves (1927) is a good example of the smaller formats she liked to work with. B. Hepworth also worked on the human form: up to the early 1930s, her squat, heavyset bodies show her interest in so-called primitive works – an interest shared by many artists from the two previous decades. Indeed, Hepworth and her second husband, the painter Ben Nicholson, were very involved in the constantly evolving Hampstead and Paris art communities.

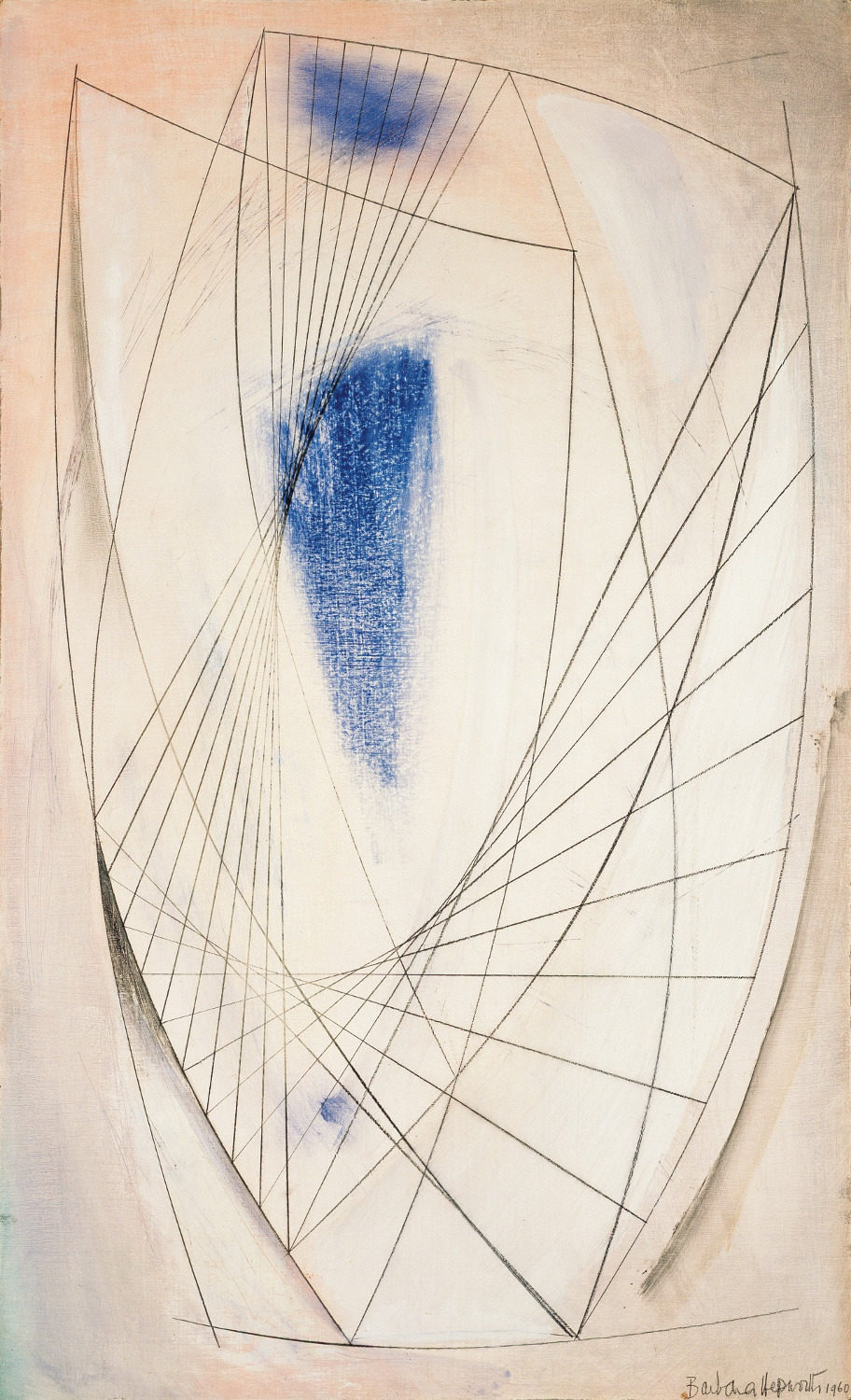

In 1933, she became a member of the Abstraction-Création group with Arp, Gropius, Le Corbusier, Hélion, and Mondrian; in 1934, she took part in the Unit One experiment with H. Moore and the critic Herbert Read, and she met Picasso, Brancusi, and Giacometti in Paris. Created in 1931 (and destroyed during World War II), her first Pierced Form would go on to inspire H. Moore: its hollowed out shapes with one, and later several openings would become the characteristic trait of her work and enable her to explore the way materials react to light and the contrasts between the inner and outer surfaces of predominantly curved geometric shapes. Her first pierced forms coincided with her first “groups”. Their titles, such as Mother and Child (1934) and Large and Small Form (1934), suggest an assimilation of form and figure. While her move toward abstraction has sometimes been attributed to motherhood, it is however more tempting to attribute it to her collective experiments of the 1930s, all the more so because her “forms”, often designated by their numbers, quickly became free geometrical explorations emancipated from any reference to the body. From 1940, the addition of ropes and colours enhanced her ovoid sculptures with straight lines and contributed to the giving the effect of perspective. The war forced B. Hepworth’s family to take refuge in Cornwall and inspired the artist to return to figuration, as can be seen in a series of drawings depicting surgeons at work (Reconstruction, 1947). A precarious refuge at first, the garden studio of her new home became a landscape in which she began working on outdoor sculptures, some of which would become her most iconic. Their names – Pelagos (1946), Anthos (1946), Eidos (1947), Elegy III (1966) – refer to the sea and to Greece, long before she visited the country. This was the period during which she was officially recognised: in 1950, two years after H. Moore, she represented British sculpture at the Venice Biennale. Her formats became increasingly large, in response to the public commissions she began to receive, which also prompted her to opt for lighter, more resistant and ductile metals, like bronze, copper or brass, starting in the 1950s. This is the case with Meridian (1958-1960), a five metre tall bronze made for State House in London. The year following Hepworth’s death in an accidental fire at her studio in St Ives, the location was converted according to her wishes into the Barbara Hepworth Museum, which became an extension of the Tate Gallery in 1980. A second museum dedicated to the sculptor, the Hepworth Wakefield, opened in 2011 in her hometown.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

The Studios at the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, St Ives

The Studios at the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, St Ives  Barbara Hepworth

Barbara Hepworth