Barbara Regina Dietzsch

Charlotte Brooks, “Botanical Art in the Age of Enlightenment: Barbara Regina Dietzsch and her circle”, Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library 16 (June 2018): pp. 7–17.

→Heidrun Ludwig, “Nürnberger Blumenmalerinnen um 1700 zwischen Dilettantismus und Professionalität [Nuremberg Flower Painters Around 1700 Between Dilettantism and Professionalism”, Kritische Berichte 4 (1996): pp. 21–29.

→Eyke Greiser, “Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706–1783) und ihre Familie ‘Gemälde auf Pergament’—Präsentationsformen und Markt [Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706-1783) and her Family ‘Paintings on Vellum’ – Forms of Presentation and the Market]”, in Michael Roth, Martin Sonnabend et al. (ed.), Maria Sibylla Merian und die Tradition des Blumenbildes von der Renaissance bis zur Romantik [Maria Sibylla Merian and the Tradition of Flower Painting from the Renaissance to Romanticism]. Munich: Hirmer, 2017, pp. 205–219

German still-life painter.

Active in Nuremberg, a major centre for botanical illustration, Barbara Regina Dietzsch specialised in watercolour drawings of plants and animals. Her flower drawings are considered amongst the most accomplished and important examples of botanical art in 18th-century Europe. Enjoying an international reputation in her lifetime, B. Dietzsch sold her works widely and attracted commissions from across Europe.

Like many successful women artists of the 18th century, B. Dietzsch grew up in an artistic family. Her father, Johann Israel Dietzsch (1681–1754), a landscape painter and engraver, trained his six children to participate in the family workshop’s production of flower and animal still life compositions. Within this context, B. Dietzsch and her sister Margaretha Barbara Dietzsch (1726–1795) could develop their artistic practice independent of the societal restrictions imposed by the local guild and artistic academies that excluded women from their ranks. Variations of similar compositions of flower and animal studies (nearly all unsigned) are attributed to the two Dietzsch sisters and other Dietzsch family members, as well as Ernst Friedrich Karl Lang (1748–1782), a student of B. Dietzsch’s, reflecting the prevalent role of repetition and reuse between artists. Contemporary auction catalogues indicate that B. Dietzsch also painted birds, shells and landscapes, in addition to botanical subjects.

Within the collaborative workshop, B. Dietzsch was the principal flower painter and received significant critical attention during her lifetime. She was also well-known to the scientific community in Nuremberg, referred to as “our countrywoman, Miss Barbara Regina Dietzsch, now quite famous everywhere” by the physician and botanist Christoph Jacob Trew. Along with other leading botanical artists of the time, B. Dietzsch and her sister contributed drawings to be translated into engraved illustrations for significant scientific and natural history publications, such as Trew’s Plantae Selectae (1750–1773) and Hortus nitidissimis (1750–1786). Despite her renown, B. Dietzsch remained with her family in Nuremberg, never marrying and turning down an invitation to paint for the court of Bavaria.

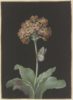

Works attributed to B. Dietzsch frequently set a single flowering plant against an opaque black background painted on vellum. Each aspect of the flower is meticulously rendered in careful detail, and insects enliven the composition. Her delicate manipulation of gum arabic and opaque watercolour (gouache) – mixed to varying degrees of opacity and layered to create detailed visual effects – achieves a high degree of verisimilitude, reflecting the tradition of melding scientific and aesthetic interests in the natural world found in the work of her predecessors in Nuremberg, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Hans Hoffmann (1530-1591). B. Dietzsch’s penchant for precise detail allies her with the scientific impulse, but the insect visitors that occupy her flowers imbue her work with a charmingly episodic, almost narrative quality. Her gestural application of pigment to the flower’s petals and leaves and the portrait-like presentation of the plants suggest that these works were intended as miniature paintings rather than solely botanical illustration.

Her use of parchment, or vellum – historically a preferred working surface for delicate applications of opaque watercolour – points to the luxury status of her works. Often smaller than a sheet of notebook paper, these flower portraits may have been kept in an album of collected drawings or displayed in groups to evoke the sense of a garden indoors. On many examples of her works, the presence of a gold border– likely added later – further supports the assumption that they were collectors’ items, valued both for their beauty and their reflection of the artist’s reputation as an accomplished flower painter.

A biography produced as part of the programme “Reilluminating the Age of Enlightenment: Women Artists of 18th Century”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2024