Barbro Östlihn

Barbro Östlihn. New York Imprint, exh. cat., Gothenburg Museum of Art, Göteborg (12 March-25 September 2022), Göteborg, Gothenburg Museum of Art, 2022

→Annika Öhrner, Barbro Östlihn & New York. Konstens rum och möjligheter [Barbro Östlihn & New York. The spaces and potential of art], Stockholm-Göteborg, Makadam, 2010

→Barbro Östlihn, Liv och Konst [Barbro Östlihn, life and art], exh. cat., Norrköpings Konstmuseum, Norrköping (29 March-25 May 2003), Norrköping, Norrköpings Konstmuseum, 2003

Barbro Östlihn (1930-1995): Stockholm-New York-Paris, Swedish Institute, Paris, March-July 2025

→Barbro Östlihn. New York Imprint, Gothenburg Museum of Art, Göteborg, March-September 2022

→Barbro Östlihn. En retrospektiv [Barbro Östlihn. A Retrospective], Norrköpings Konstmuseum, Norrköping, March-May 2003

Swedish painter.

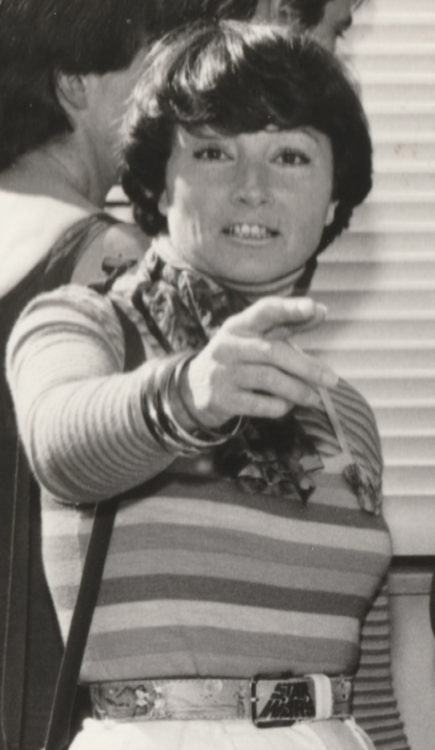

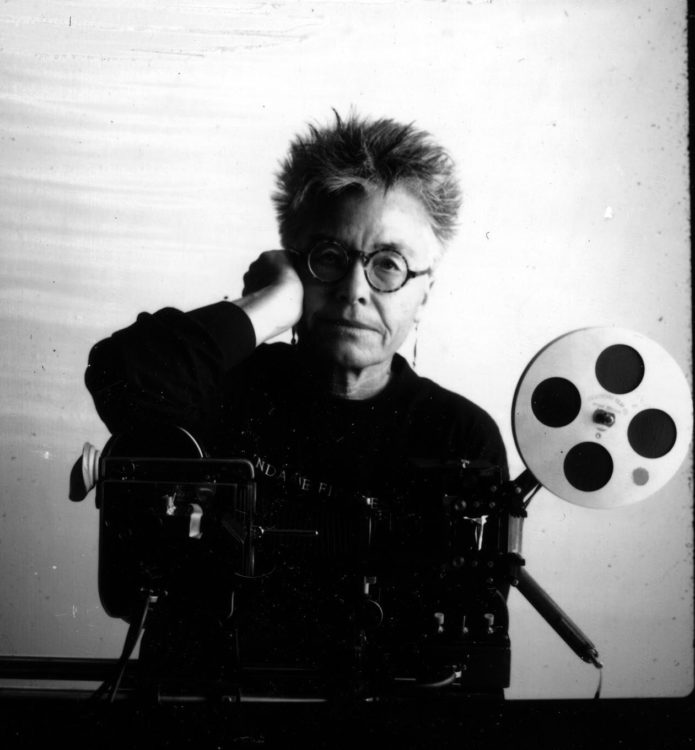

Working first in Stockholm and later in New York and Paris, Barbro Östlihn developed an innovative pictorial language blending abstraction with figuration. In 1961, after training at various Stockholm art schools, the young painter moved to New York with her second husband, the artist Öyvind Fahlström (1928–1976). They made their home in lower Manhattan, a few blocks from Wall Street, moving into the loft formerly occupied by Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008), whom they had met together with Jasper Johns (1930–) in Sweden a few months earlier.

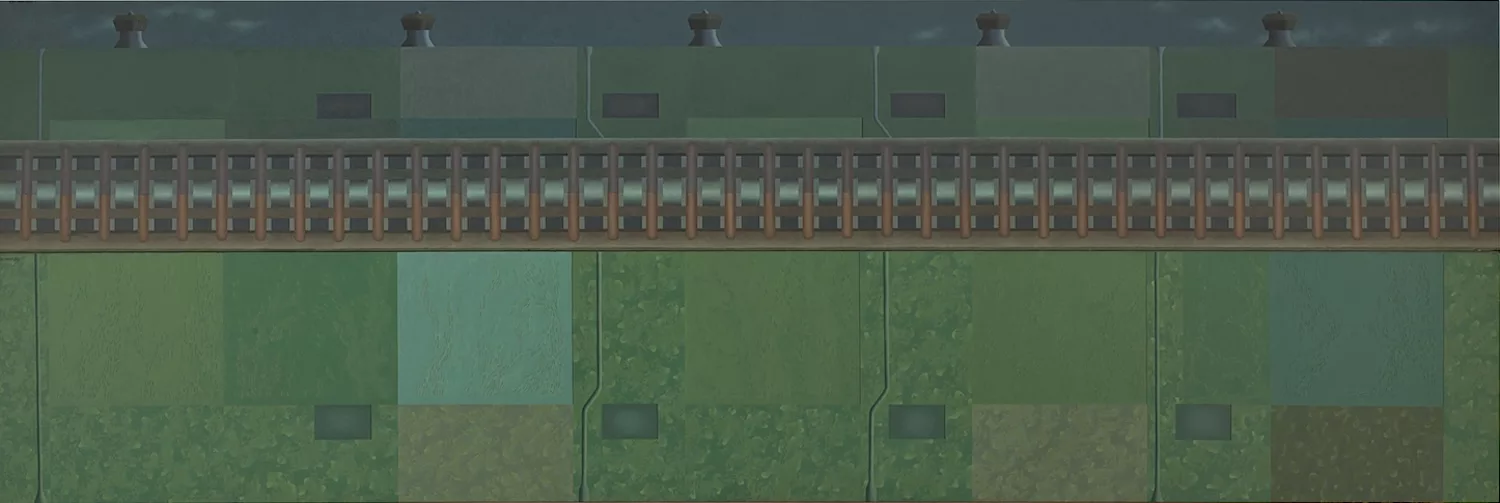

There, amidst the upheavals of a metropolis in flux, B. Östlihn crafted her own unique style independent of existing art trends. Fascinated by the dance of demolition, construction and renovation underway in that still notorious part of the city, she made large oil paintings of skyscraper façades. But the fronts were not her sole focus – she could be equally captivated by the outline of a lost structure on a side wall, or the back of a building, complete with fire escapes. Whether belonging to a residential high-rise or a factory (as in New York Steam Company, 1962), walls filled her canvases from one edge to another, embedding softer, more organic elements into their rigid architectural symmetry as they took form. Though reality always served as B. Östlihn’s starting point, her method – reducing a scene to a few planes, tightening the frame onto a single architectural feature and using palettes that stepped away from the inspiration’s actual colours – distilled her subject matter into a more abstract vein.

Some works, such as Gas Station (1963), are evocative of surrealism: the viewer wonders from what angle she painted those pennants strung up on wires. Others, like Washington Bridge (1962), are reminiscent of Op Art. Still others have been interpreted as nods to Pop Art. But B. Östlihn’s oeuvre continually resists categorisation, existing in an abundance of layers, flattened and compressed perspectives, and jumbled or merging planes.

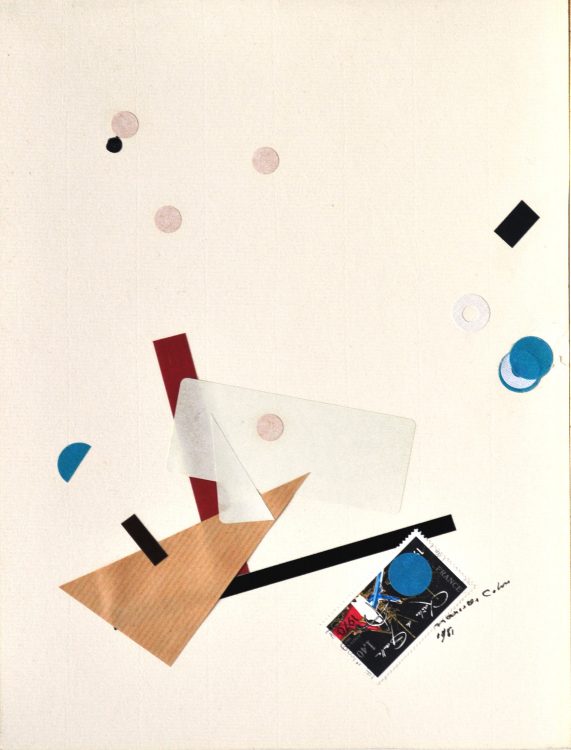

In 1975, her marriage to Ö. Fahlström, whose career she had extensively supported and with whom she had often coproduced works, came to an end. She decided to return to Europe and make a home for herself in Paris, a city that had always inspired her. She settled there in 1976 with the French artist Charles Dreyfus (1947–). From this point on, her paintings became increasingly abstract. In addition to building façades, she began to depict other flat surfaces such as parquet flooring and, influenced by her visits to Spain, the Mediterranean Sea (Tarragona, 1980). Their connections to the real world survive only in their titles, which reference the inspirations behind them. Highly uniform geometric macroforms populate her canvases from this period, whilst colour unfolds in shades and gradations. And though her palettes continued to consist of soft, muted earth tones, her paintings sparkle.

B. Östlihn earned recognition and exhibited at galleries in Sweden, the United States and France, and her work entered many prestigious public collections (the Centre Pompidou in Paris and Moderna Museet in Stockholm, amongst others). One retrospective was organised during her lifetime, at Moderna Museet, in 1984. It was only in 2003 that the first major solo exhibition of her work was held, followed by another in 2022, in the Swedish cities of Norrköping and Gothenburg respectively.