Claudia Triozzi

“Entretien par Béatrice Lapadat”, in Claudia Triozzi. Pour rien mais dans le bon sens (dossier de presse Festival d’automne), March 2024, online: https://www.festival-automne.com/storage/medias/claudia-triozzi_o_1i338cc85gvg19iqtv4d1m1sufh.pdf

→Derrien, Marianne, Cotinet-Alphaize, Jérôme, Some of Us : Artistes contemporainexs. Une anthologie, Paris, Manuella éditions, 2024

→Brignone, Patricia, La Ménagerie de verre, nouvelles pratiques du corps scénique, Romainville, Al Dante, 2006

Pour une thèse vivante, galerie Ygrec-ENSAPC, Aubervilliers, 15 May–3 June, 2021

→Le Juste prix, Fondation d’entreprise Pernod Ricard, Paris, 19 May–12 June, 2021

→Jeux, Rituels et récréations, Gare Saint-Sauveur, Lille, 7 September–5 November, 2017

French-Italian choreographer, set designer and visual artist.

Claudia Triozzi began her classical dance training as a child. Later, for two years in the early 1980s, she worked alongside other women on a factory assembly line, against the backdrop of Italy’s Years of Lead. The experience was grounded in the body and the real, and would provide a link between the artist’s studies in dance and her approach to contemporary creation. She attended a number of workshops in Milan and Paris during this period, notably with Carolyn Carlson (1943–), which helped launch her career.

C. Triozzi moved to Paris in 1985. The Nouvelle Danse Française movement was in full swing, and throughout the 1990s she worked with choreographers including Odile Duboc (1941–2010), Georges Appaix (1953–) and François Verret (1955–). Her performance in the 1991 production of Villanelles by O. Duboc brought her public acclaim. Following her collaboration with F. Verret on Rapport pour une académie [Report to an Academy, 1995], she began to create her own productions, in which bodies, gestures and voices come together to form tableaux anchored in real time (the time it takes to smoke a cigarette, or for a cow to be butchered, for instance). Repurposed domestic objects and machines form scenic mechanisms, and thus the works combine dance and the visual arts, with each play benefitting from its own original set design conceived by the artist herself.

Her first work, Park (1998) is at once a dance, a performance and a tableau vivant. In it, the feminine exists as a space of alienation, play, pleasure and projection, connoted by a series of artifices and inappropriate gestures. A manifesto both sarcastic and poetic, in Park the mechanical body and the instinctual body come together such that meaning becomes delirious, evoking the avant-garde. The artist appears dressed in an apron, sitting with her head stuck in a steam cooker designed for hot dogs, a gesture that echoes a number of iconic feminist performances such as Martha Rosler’s (1943–) Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975).

C. Triozzi has been professor of art education at the École Superieure d’Arts de Rueil-Malmaison (2006–2011) and at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Art de Bourges (2011–2018). She currently holds the same post at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris-Cergy (since 2018). Pour une thèse vivante [For a Lively Thesis, 2011–2019] was developed within this context: a research project in the form of six staged episodes, its aim is to function as a doctoral thesis ‘en acte’. Through it, the artist proposes the collective construction of a national centre for choreography out of earth and straw, at once precarious habitat, space of welcome and a metaphor for a utopian school. Butchers, knotmakers and psychoanalysts amongst others are invited to practice their craft on stage, while the work also involves a dimension of critical writing.

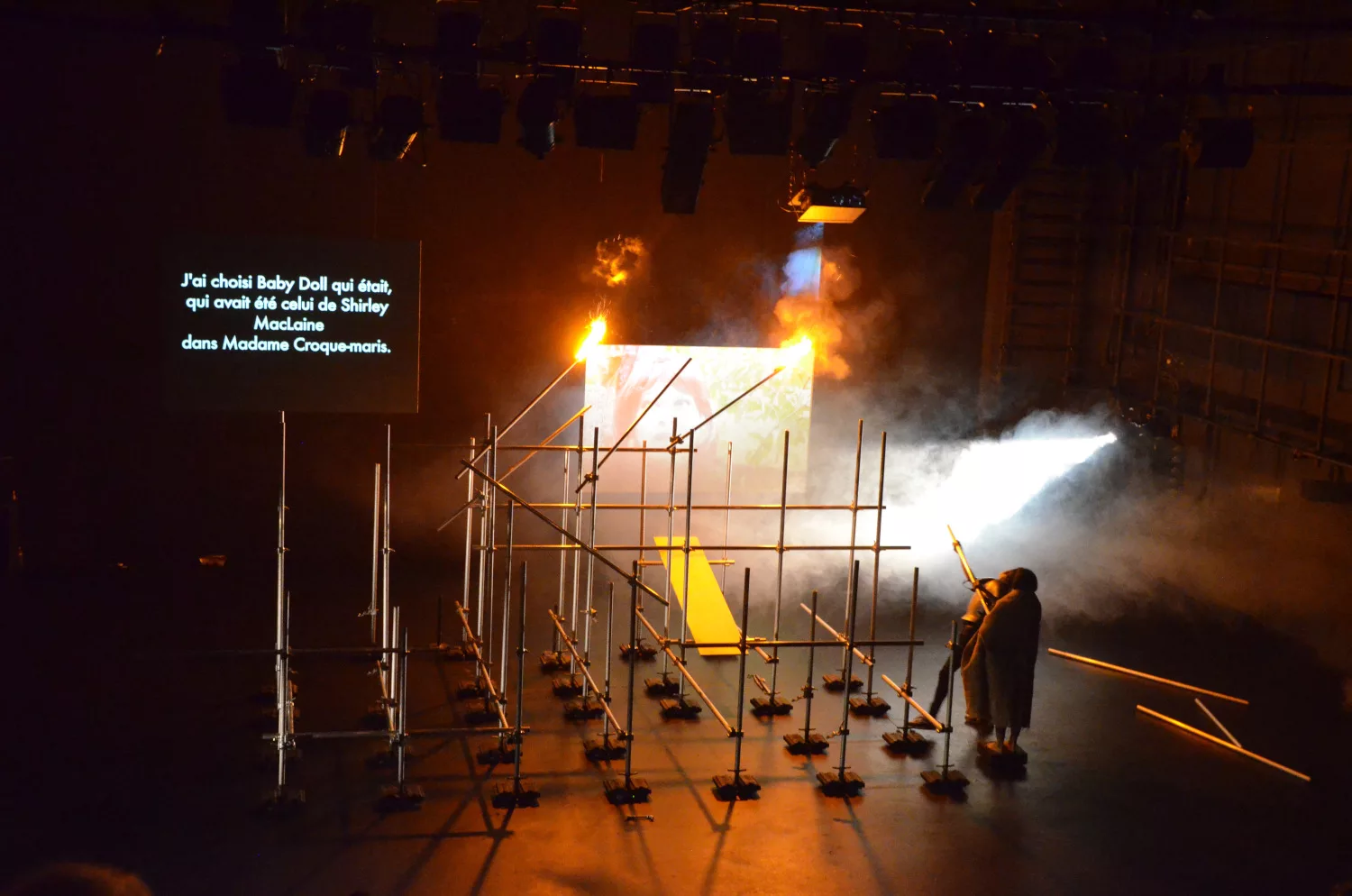

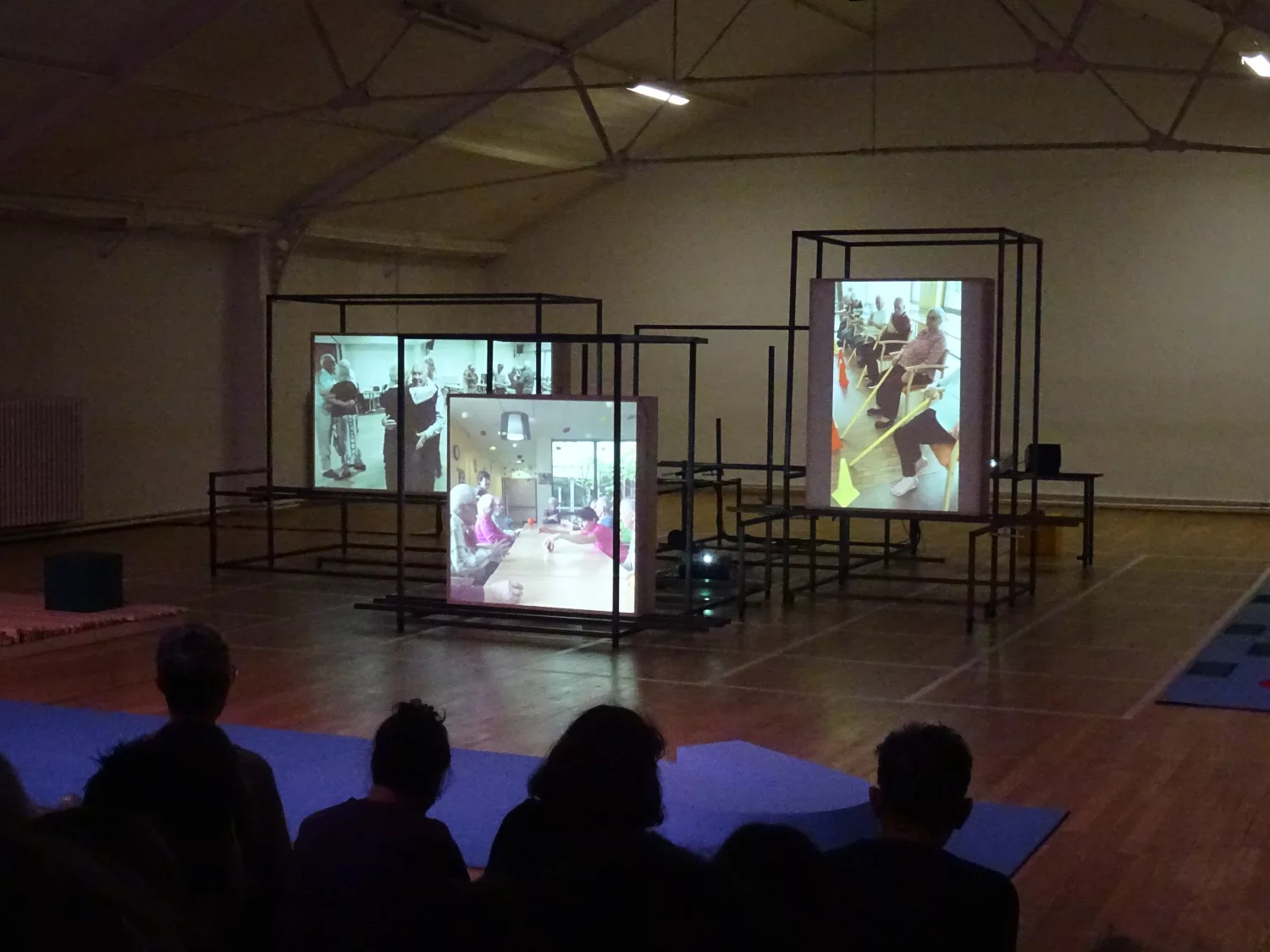

Pour rien mais dans le bon sens [For Nothing But in a Good Way, 2022] emerged from workshops conducted in retirement homes with older people. A project of transmission and investigation, it constitutes a reflection on what exercise, dance and interaction with objects and the voice may offer to those confined to a spacetime marginalised by society. Presented at the Festival d’Automne (2024) alongside a video installation and an architectural tubular construction, it brings to mind other scenic devices previously created by the artist, notably Boomerang ou le retour à soi [Boomerang or the Return to Oneself, 2013]. By recording the stories, echolalia and vacillations of the participants, C. Triozzi reflects on the relationship of the body to the machine, the physical and emotional incorporation of gestures of labour, and their poetic displacement towards the realms of dance.