Constance Stuart Larrabee

Constance Stuart Larrabee, South Africa, 1936-1949, exh. cat., Washington, Smithsonian Institution, September 1998 – February 1999, Washington, Smithsonian Institution PressConstance Stuart Larrabee, South Africa, 1936-1949, exh. cat., Washington, Smithsonian Institution, September 1998 – February 1999, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press

→Marek Bartelik, « Constance Stuart Larrabee », Artforum International, vol. 34, 1996

→Constance Stuart Larrabee : Tribal Photographs, cat. d’exp., Washington, Corcoran Gallery of Art, April – June 1984Constance Stuart Larrabee : Tribal Photographs, cat. d’exp., Washington, Corcoran Gallery of Art, April – June 1984

Constance Stuart Larrabee : WW II Photo Journal, National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1989

British-South-African photographer.

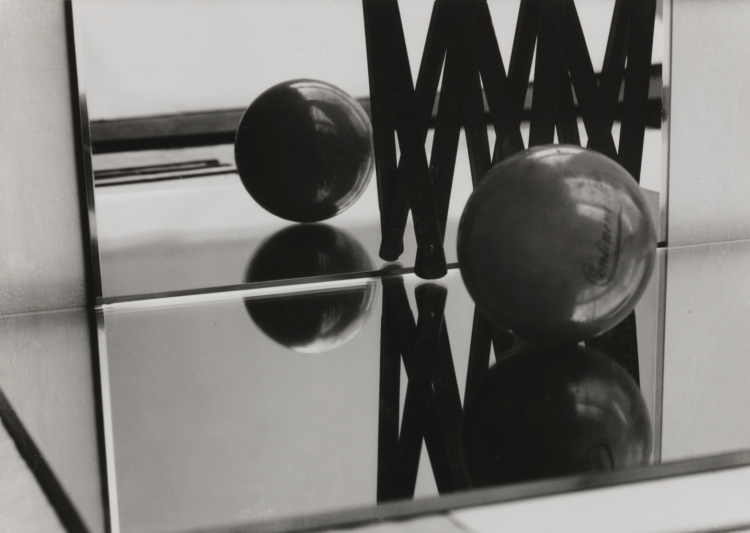

Constance Stuart arrived in the Union of South Africa with her mother shortly after her birth in Camborne, a mining town in Cornwall, and grew up in Pretoria, the country’s administrative capital. Photography became her calling early on, because her maternal grandfather William John Bennetts owned a photographic business in Camborne. In 1933 she left for training in London and Munich, where she studied at the Bavarian State Institute of Photography. There she became familiar with modernist photography, twin-lens reflex cameras, and the aesthetics of black-and-white film. By 1936 she was back in Pretoria and soon thereafter established the Constance Stuart Portrait Studio. Her modern mode of portraiture attracted prominent sitters, among them politicians, artists and writers.

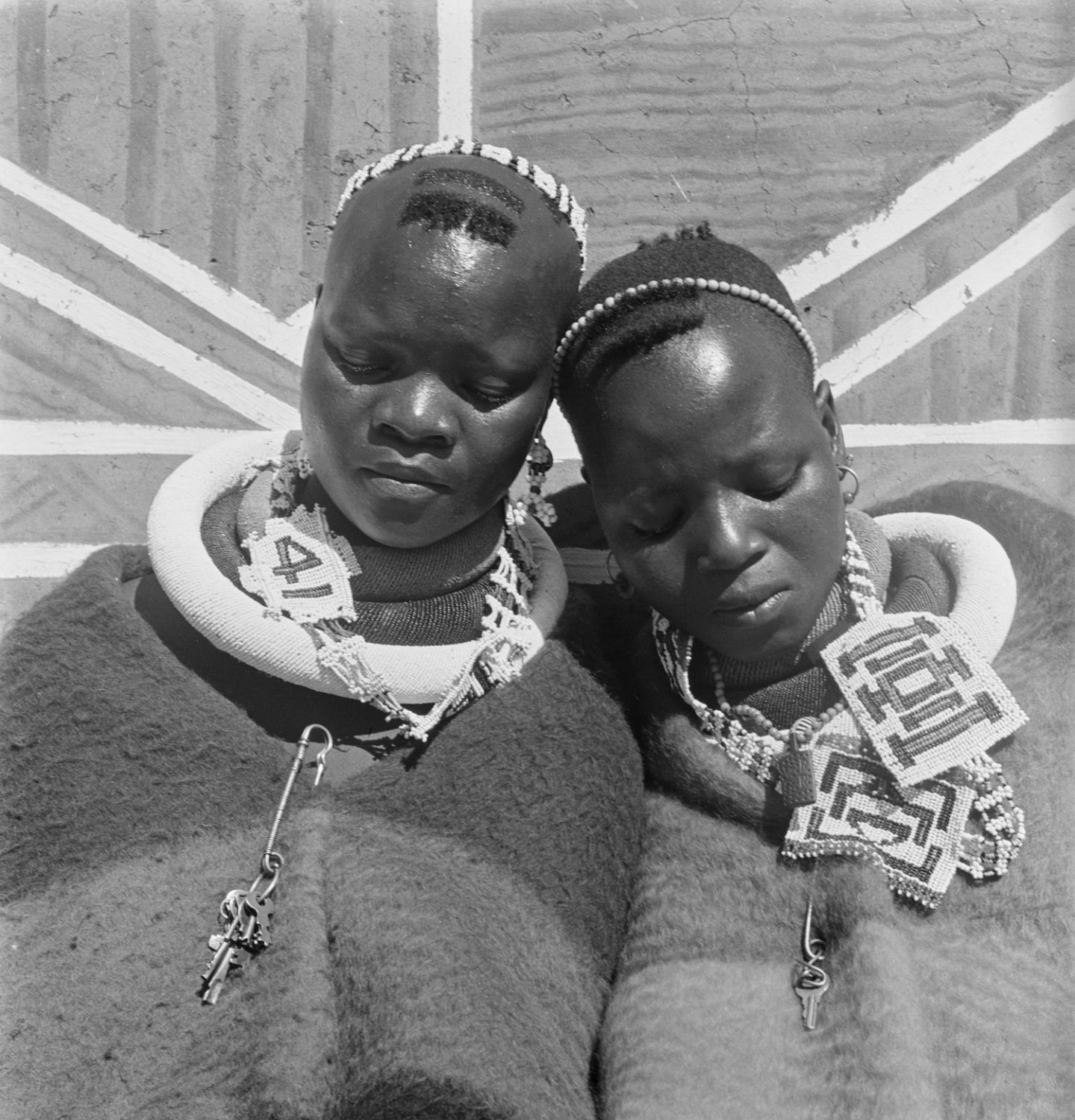

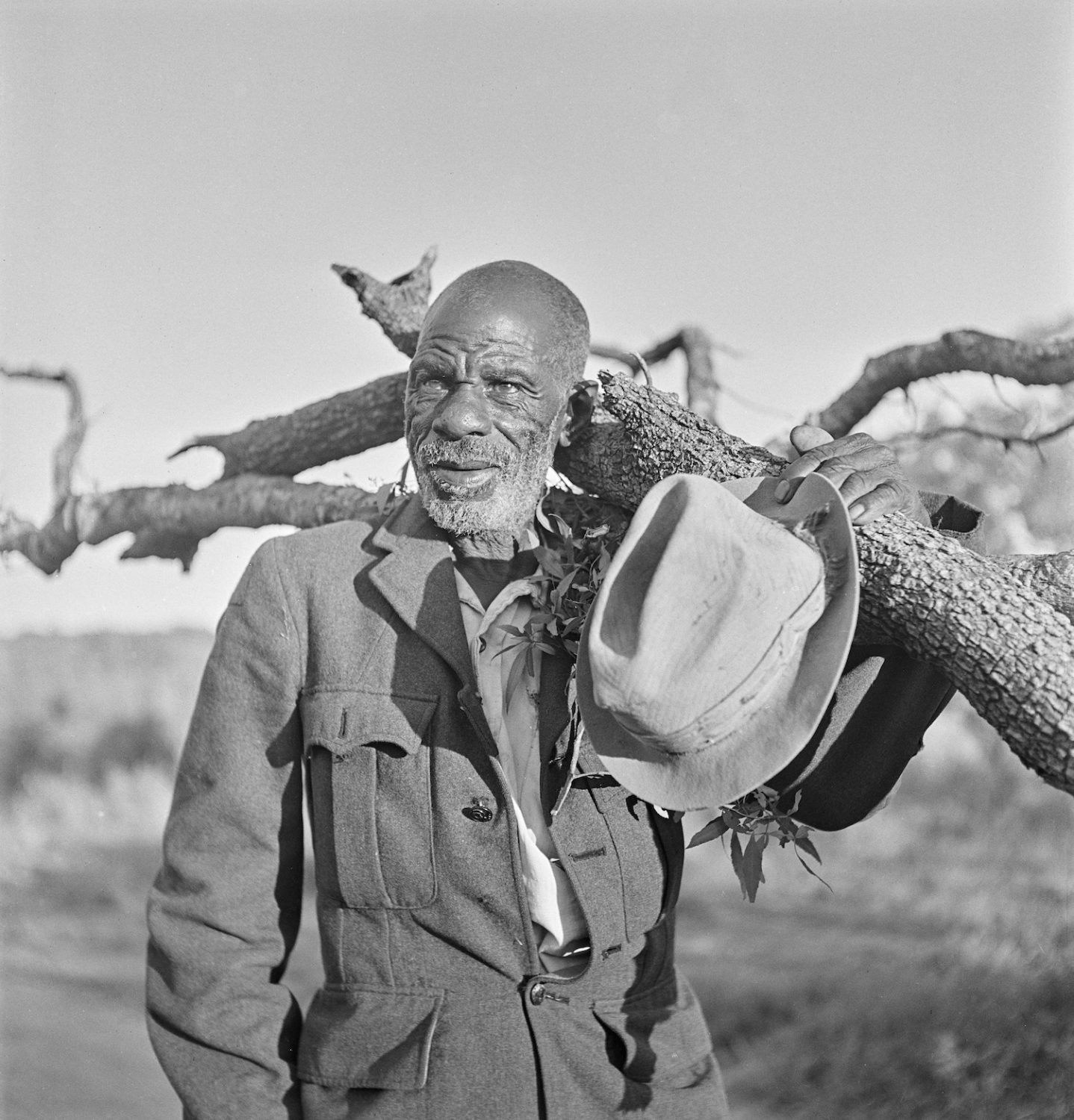

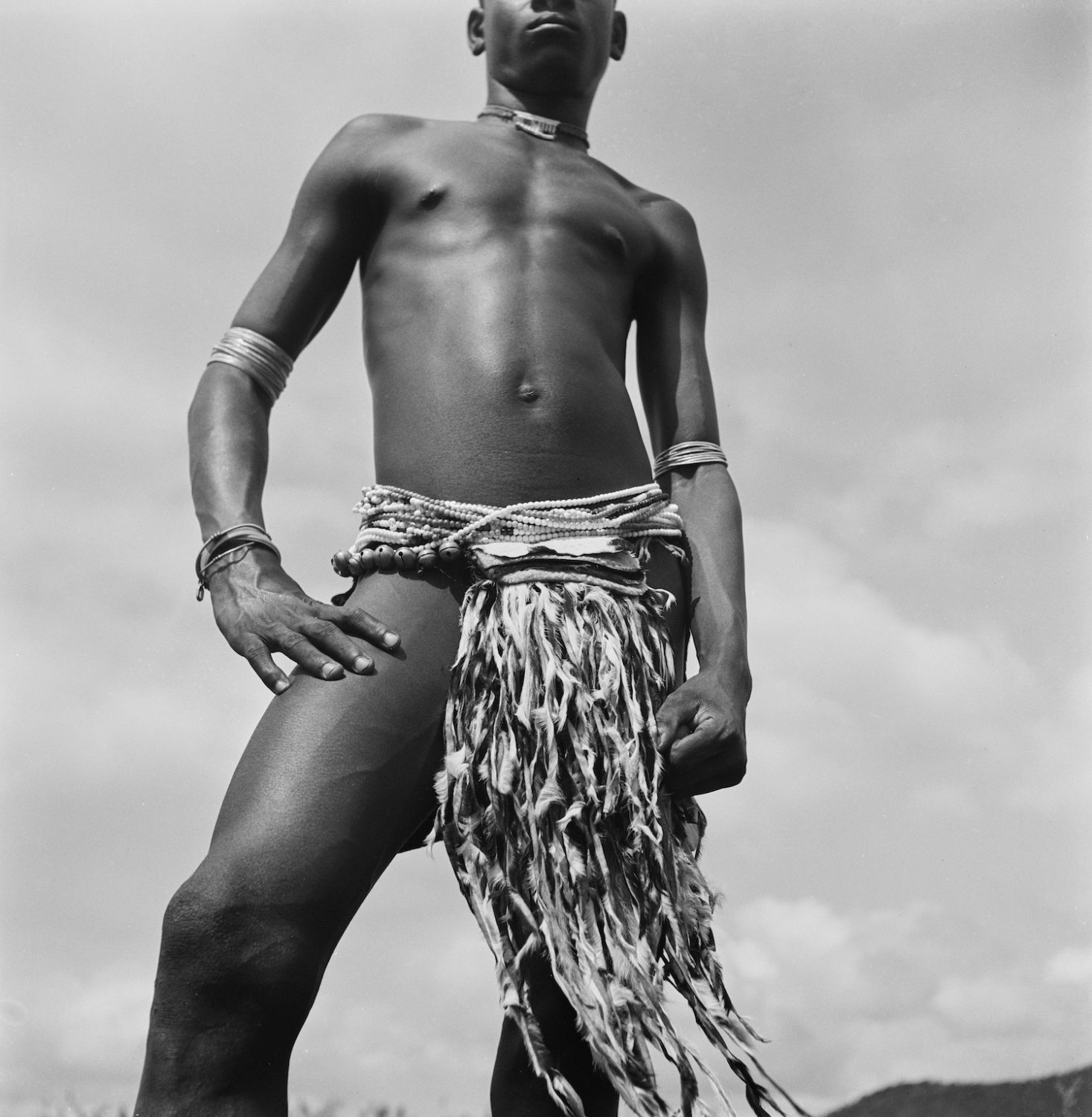

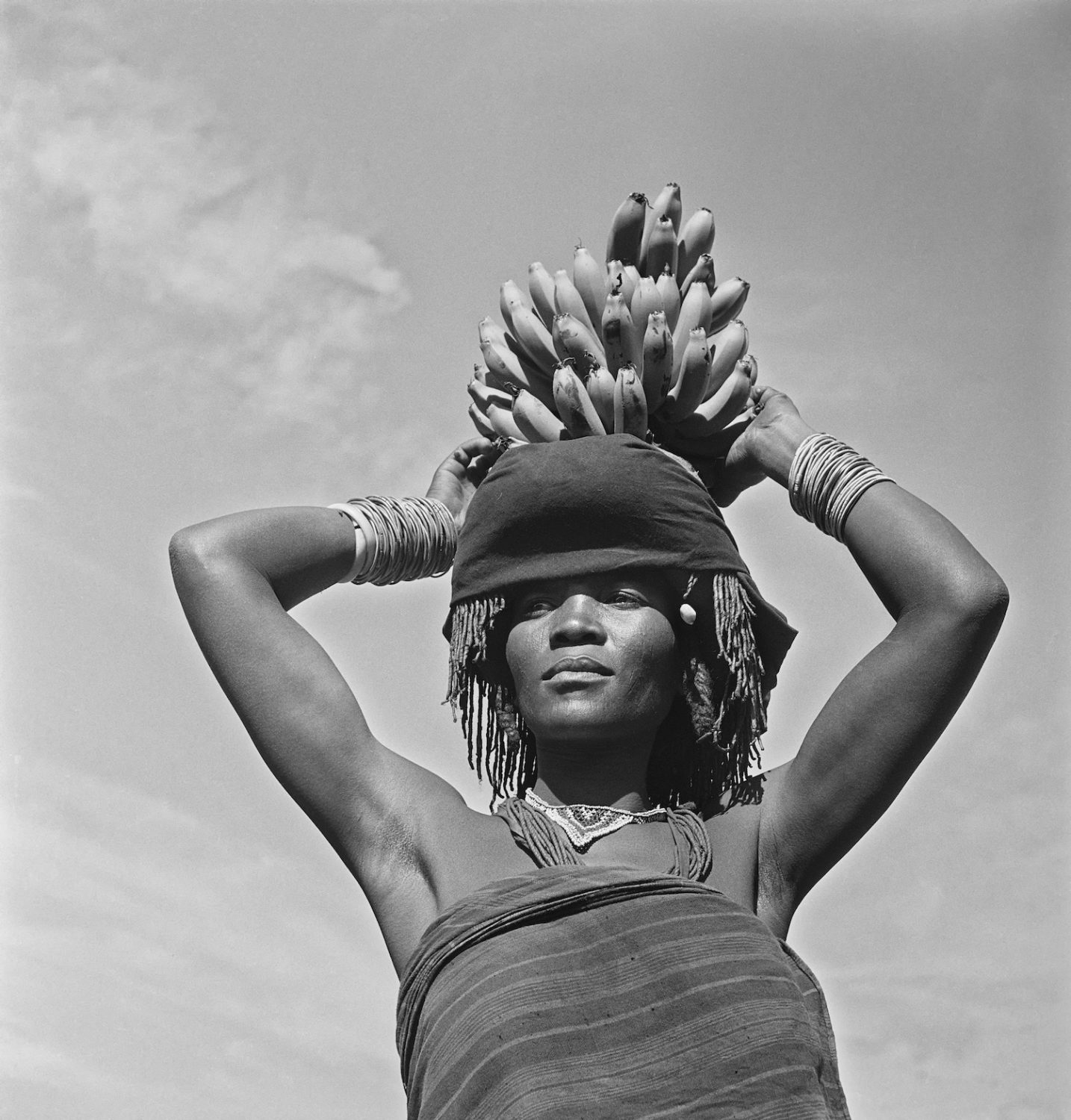

Besides her studio work, Stuart photographed South Africans of all racial backgrounds in their environments. She used a Rolleiflex and developed her signature style, including employing different camera angles, focusing on intricate details, and experimenting with light, texture and form. Fascinated with visual aspects of African cultures, C. Stuart began to visit settlements of the Ndebele peoples near Pretoria, famous for their colorful traditional attire, painted homesteads, and performances for tourists. Women and children, her favorite subjects, understood how to pose for her camera during long portrait sessions.

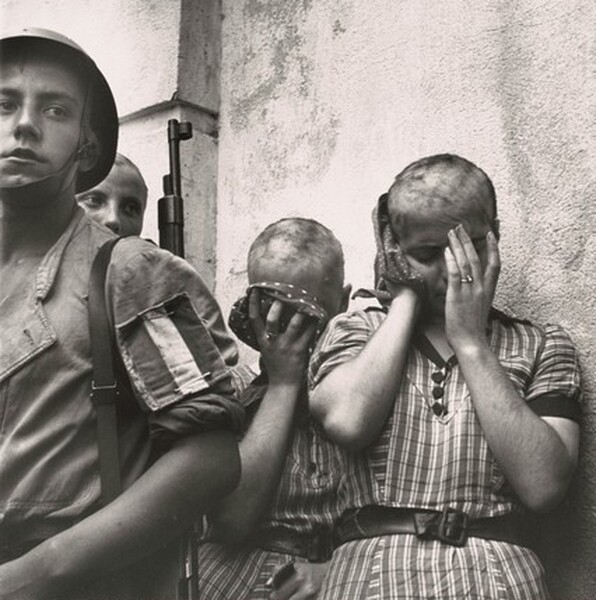

C. Stuart’s reputation as a photographer grew, and several smaller exhibitions brought her wider recognition, among them a 1944 show of photographs she had taken in 1942-1943 in the Cape Town Malay Quarter, today referred to as Bo-Kaap. Flamboyant English playwright and actor Noël Coward opened this display (The Malay Quarter, 1944). Towards the end of the Second World War, the South African Director of Military Intelligence accredited her South Africa’s first woman war correspondent on assignment for the illustrated periodical Libertas. Between July 1944 and March 1945, Stuart accompanied the South African Sixth Armoured Division and the American Seventh Army to Italy. She also encountered French and Italian resistance fighters and French and British troops. As a woman, she was not allowed to witness battles, thus she often depicted their aftermath and the human toll of war during the ongoing liberation of Europe from Mussolini’s forces in Italy and Hitler’s occupation in France.

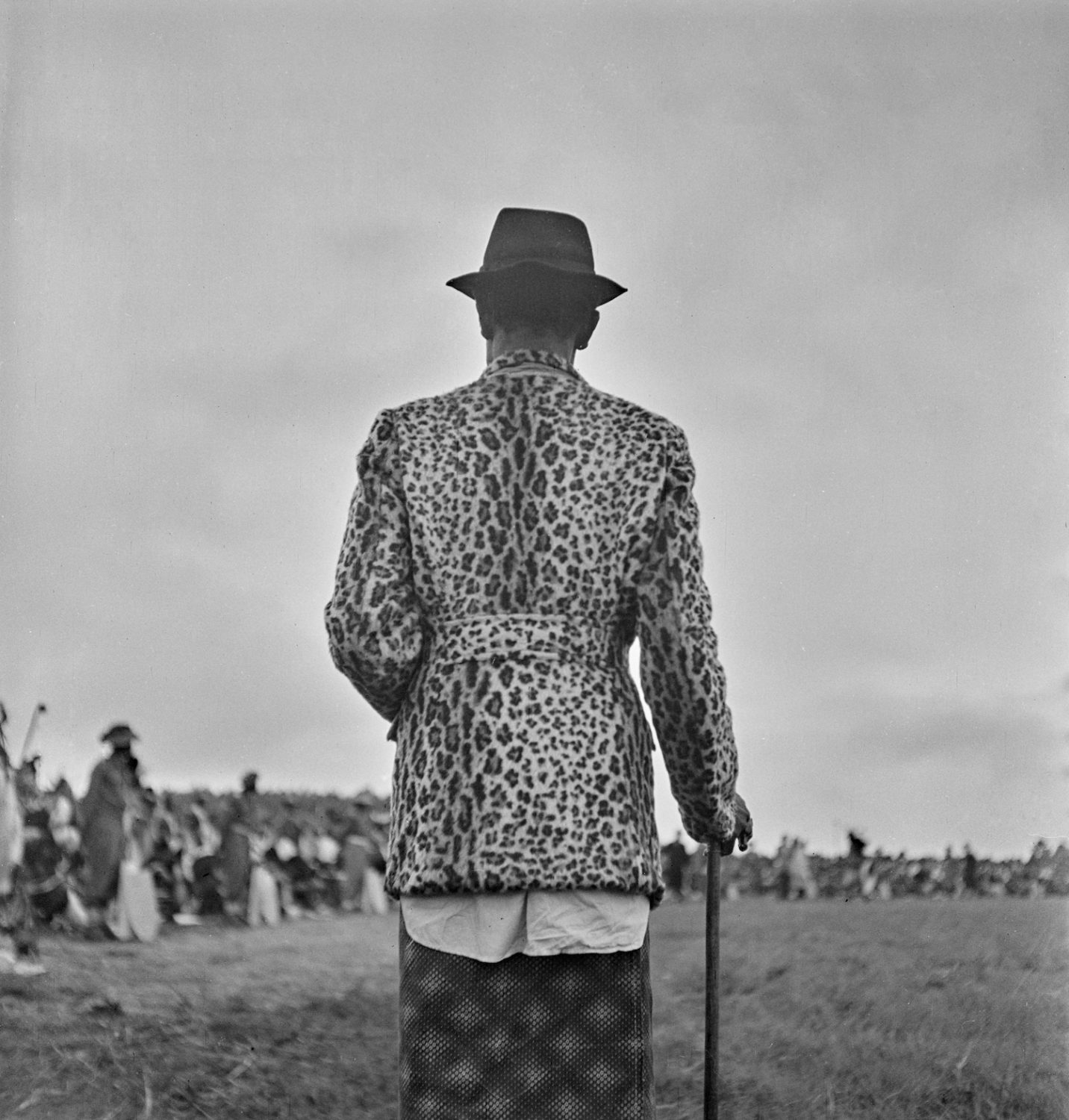

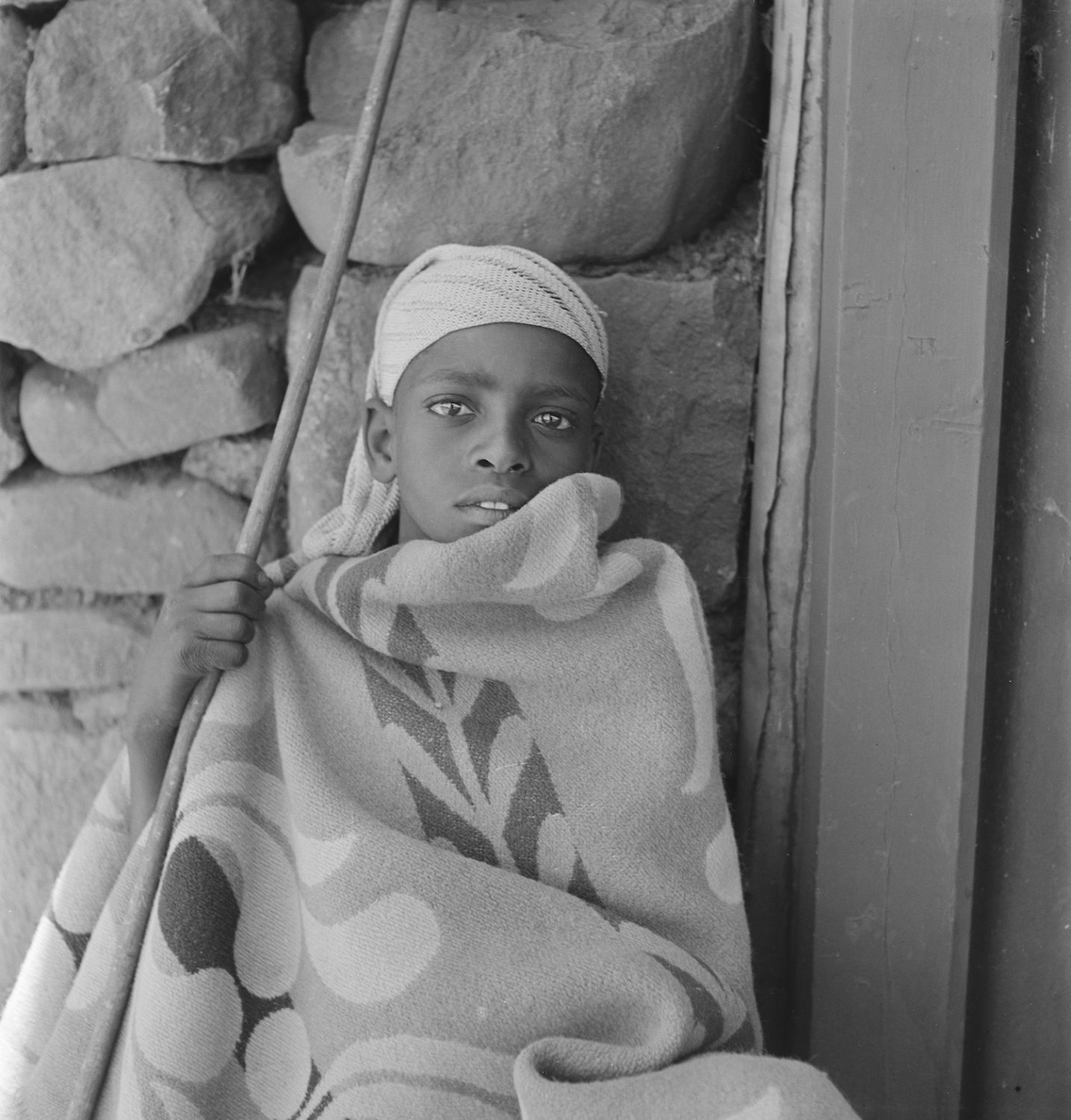

Upon her return to South Africa C. Stuart opened a second studio in Johannesburg, an unusual endeavor for an unmarried woman in a profession dominated by men. Whenever possible, C. Stuart also continued her passion of recording the life of black Africans in an effort to visually preserve their cultures. She traveled to the Xhosa, Zulu, Swazi and Lobedu peoples in so-called Homelands, rural regions where the white South African government required them to live or had forcefully resettled them.

In and around Johannesburg Stuart created images, which for viewers today bear witness to the horrendous conditions that black African workers and so-called Coloureds of various descent experienced as a result of economic marginalisation and exploitation during the era of racial segregation and, after 1948, under apartheid. Stuart ventured into the south-western townships on the city’s outskirts (by the early 1960s referred to as Soweto). She photographed in Pimville and Orlando, where non-white migrants from rural areas lived in barracks and substandard housing erected by the government. She also captured the plight of poor white South Africans, and the lives of rural Afrikaners, the descendants of early Dutch and Huguenot settlers.

Illustrated magazines thrived in the United States and C. Stuart saw another opportunity to promote her work, so in 1948 she signed up with Black Star, a picture agency in New York. Through Black Star, some of her photographs appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, Life and Vogue. In May of 1949 she arrived in New York for a three-month tour organised by the agency to familiarise her with fellow American image-makers and to show her work. While in the city, she renewed her acquaintance with Colonel Sterling Loop Larrabee (1889-1974), whom she knew from his time as a military attaché in Pretoria; they married and she stayed in the United States.

C. Stuart Larrabee and her husband enjoyed a quiet life at his estate on Chesapeake Bay in rural Maryland. Some of her South African photographs appeared in American exhibitions, among them two in Edward Steichen’s groundbreaking Family of Man at the Museum of Modern Art in 1955. She also pursued a few documentary projects, such as a 1951 photographic exploration of historic Tangier Island and its inhabitants in the Virginia part of the bay. However, as time went by her professional photographic activities declined. She devoted herself to depicting Maryland’s environment, its architecture, working people, and nearby Washington College in Chestertown, which she supported generously.

Beginning in the late 1970s, C. Stuart Larrabee’s photography experienced a renaissance through exhibitions and publications in South Africa and the United States. She enjoyed the renewed recognition of her work. However, she never fully answered the one question that curators and scholars posed during frequent interviews, namely whether she actively opposed the South African regime’s cruel segregationist and apartheid policies in her photographic oeuvre. She shied away from politics until the end of her life. She maintained that her practice was purely personal expression, her passion for photography, and a testimony to her excellent eye.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021