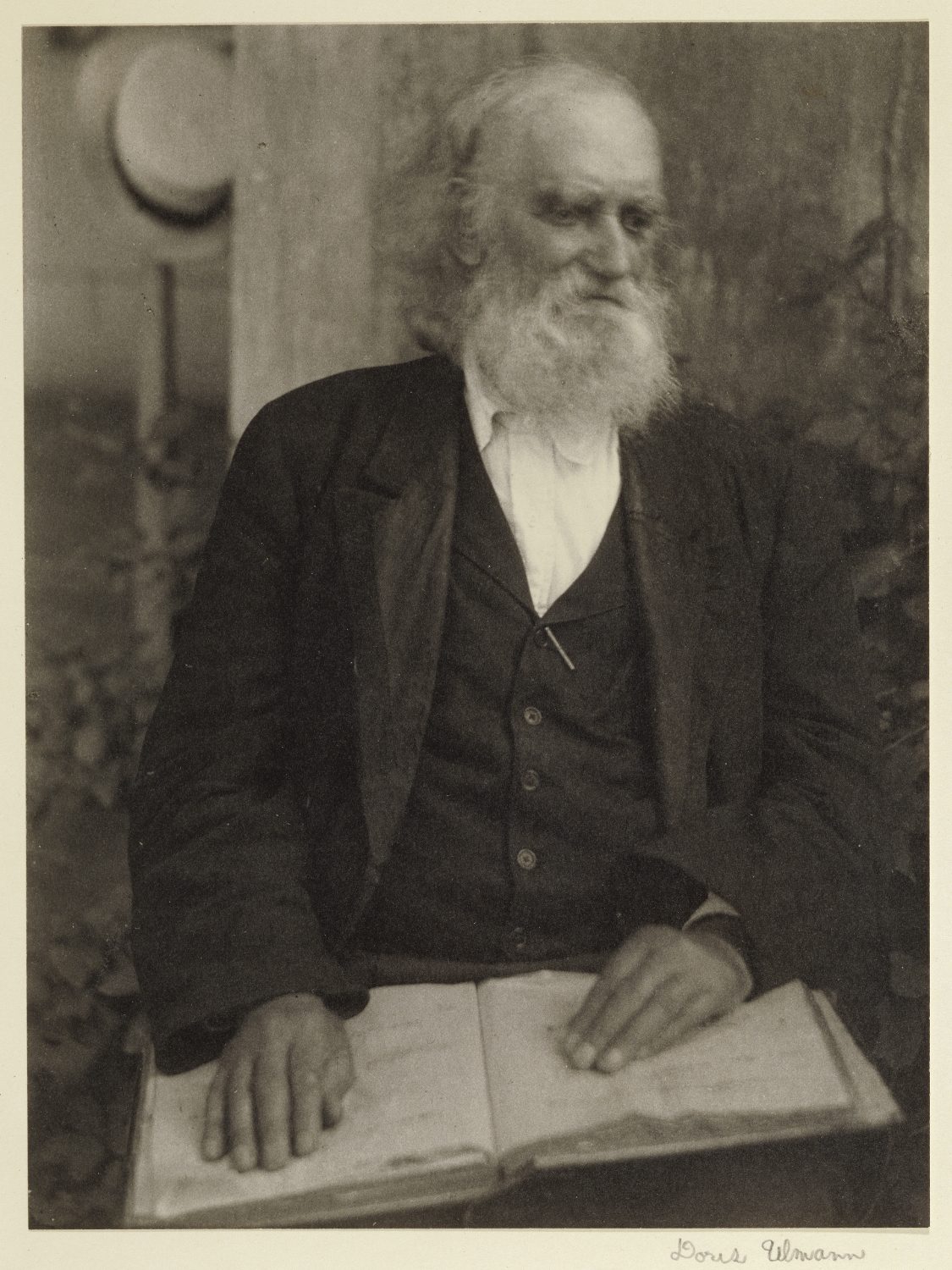

Doris Ulmann

Doris Ulmann: Photographs from The J. Paul Getty Museum, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California, 1996

→Philip Walker Jacobs, The Life and Photography of Doris Ulmann, Lexington, University Press of Kentucky, 2001

American photographer.

Born into a rich New York Jewish family, during the 1920s and ’30s Doris Ulmann recorded the daily life and crafts of rural America, which was in the process of disappearing. She occupied a key position in the history of photography, straddling the Pictorialist movement, with which she was associated through her artistic use of framing and light, and the American documentary movement of the 1930s. In 1902 she is said to have studied botany and photography under the American photographer Lewis Wickes Hine, then psychology at Columbia University (1907), but her interest in photography was really born in 1914 when she attended the courses given by Clarence H. White with, among other students, Margaret Bourke-White and Laura Gilpin (1891–1979).

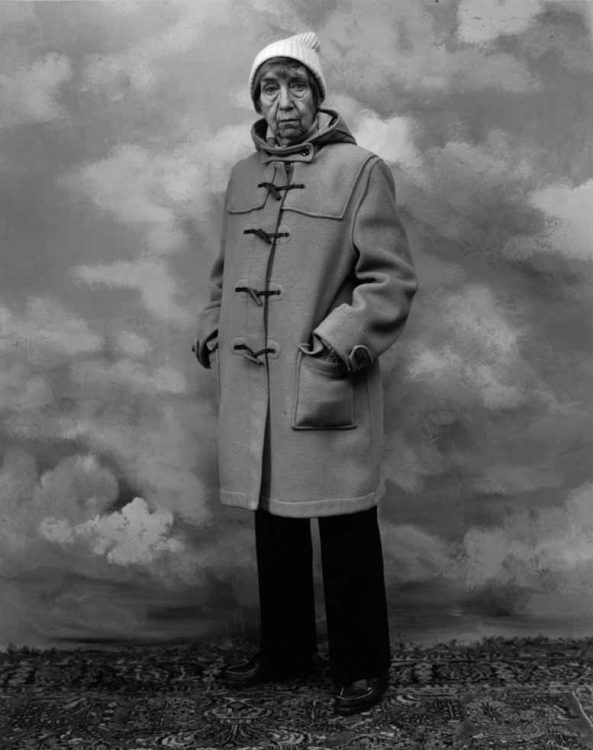

In 1913 she married the surgeon Charles Jaeger, who was also an amateur photographer. She turned professional in 1918 and joined the American Pictorialist group. In her studio on Park Avenue in New York, she made portrait photographs of writers (such as Tagore and Robert Frost) and leading figures in society, notably in the medical world. Between 1919 and 1925 she published three volumes of these rather formal portraits created with natural light.

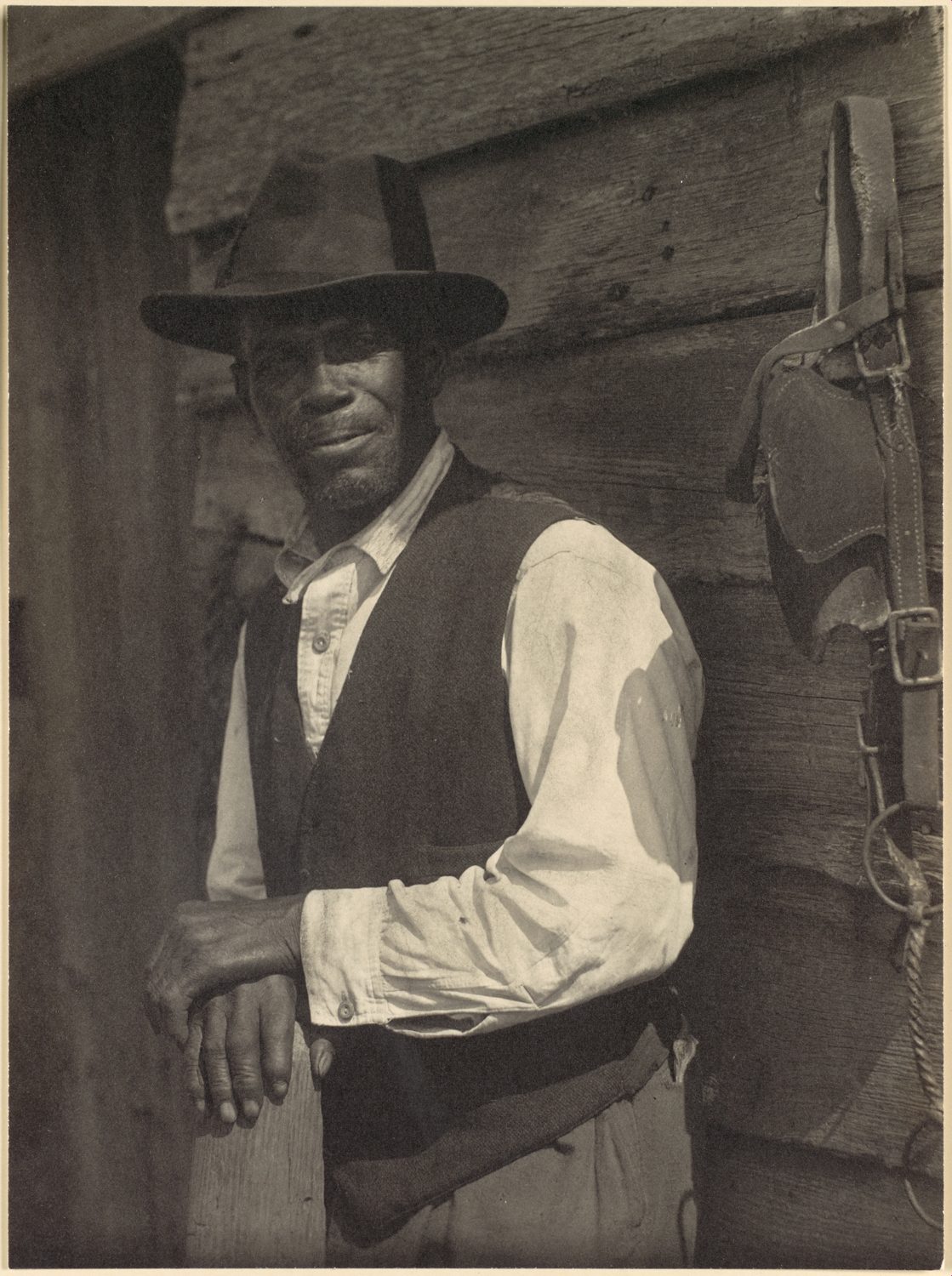

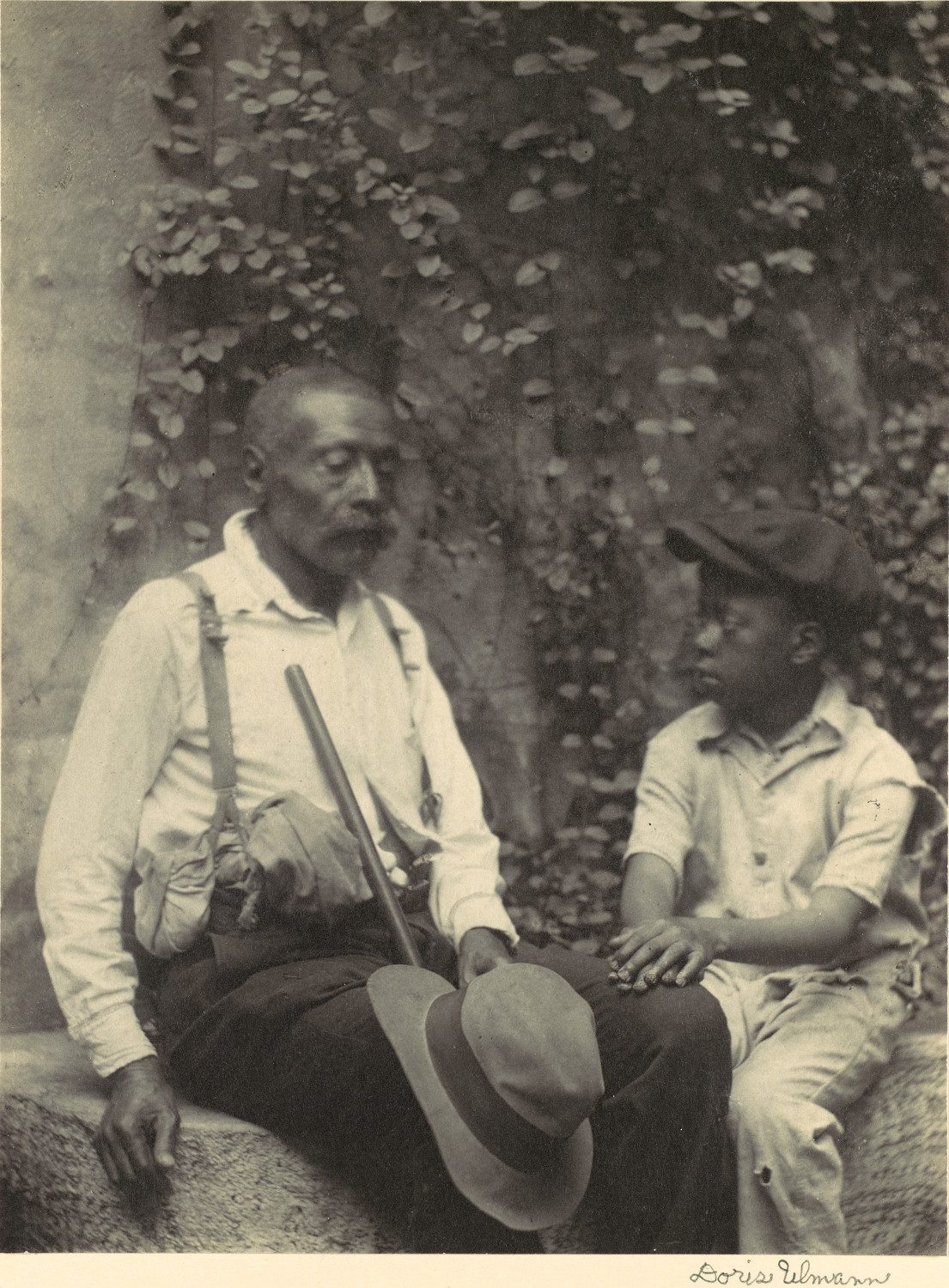

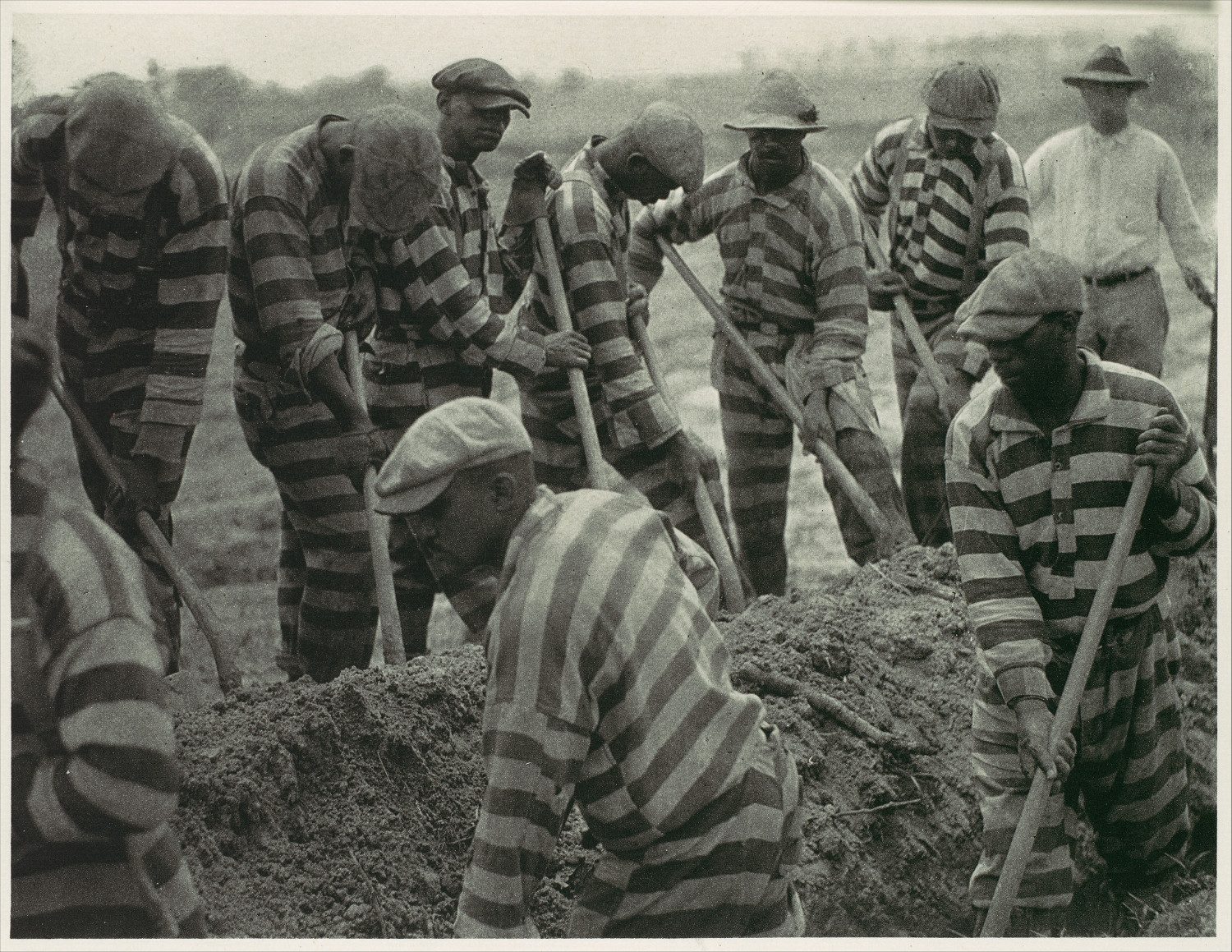

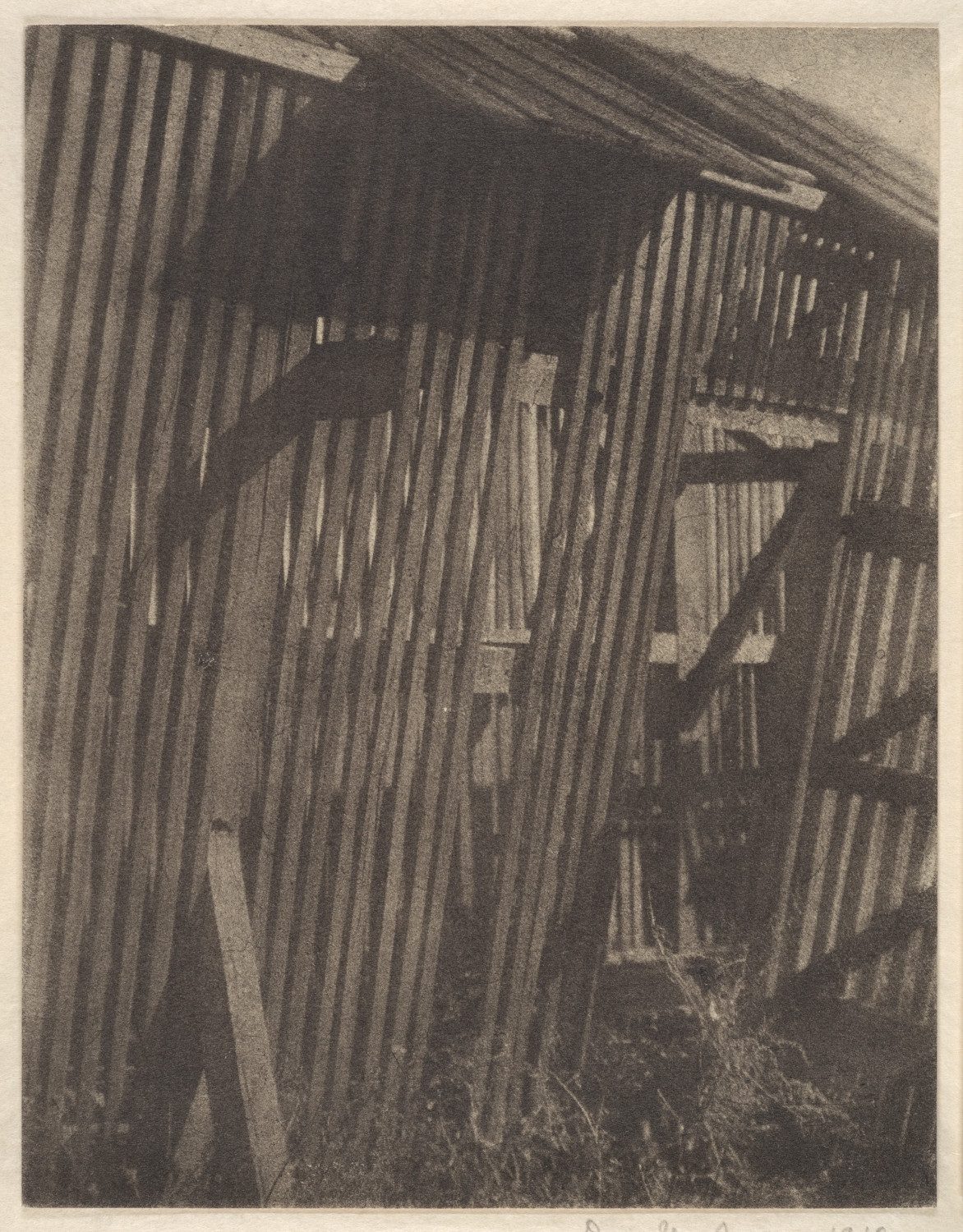

The year 1925 marked a turning point in her life: affected by her divorce and the death of Clarence H. White, to whom she had remained close, she began to travel and turned her attention to documentary photography. She met the actor, musician and student of folklore John Jacob Niles, who became her assistant, model and inspiration. They travelled together around Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee between 1928 and 1934 to photograph the costumes, customs and traditional crafts of the area. These long, physically difficult and repeated trips caused Ulmann serious health problems. Using an old camera and glass plate negatives, she produced photographs of still lifes and landscapes but above all remarkable portraits of the craftspeople of the Appalachians and of the black communities of the American South-East. The photographs used to illustrate the book by Allen H. Eaton, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (1937), show an individual at work per page, in either a full-length or waist-length image. She contributed to Roll, Jordan, Roll (1933) written by her Southern writer friend, Julia Peterkin (1880–1961), which shows the daily life of the Blacks in the southern states, in particular the Gullahs, African Americans in South Carolina. D. Ulmann then produced portraits in which the dignity of manual and agricultural work was made apparent. Her images illustrated a fragment of American history: the internal migration of the Blacks northward, the industrial revolution and the progressive disappearance of rural communities. Applied to the most varied of subjects—from the portrait of Albert Einstein, whom she photographed in the early 1920s, to the close-ups of craftsmen’s hands that she produced towards the end of her life—her style was both romantic and naturalistic. Although she was often compared to her elder Pictorialist colleagues Gertrude Käsebier and Annie Brigman, her photographs were also exhibited alongside the modernists in the 1930s. Her work was included in the exhibition International Photographers (Brooklyn Museum, 1932), which presented images by Berenice Abbott, Ilse Bing, Imogen Cunningham, Walker Evans, Florence Henri, Man Ray and André Kertész. Her systematic approach can be compared with that of August Sander in his study of German workmen, and Eugène Atget’s portraits of Paris. D. Ulmann employed a perspective that was both modern and nostalgic: like B. Abbott, she directed her efforts at documenting what is in the process of change or disappearing, which, with her keen insight, she captured at a moment of transition. Her work heralded that of W. Evans and Dorothea Lange, and it can be argued that the famous US government agency, the Farm Security Administration, would provide, in the late 1930s, an institutional framework and visibility to what she had undertaken only a few years before.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017