Gabriele Münter

Gabriele Münter, 1877-1962, Retrospektive, exh. cat., Munich, Prestel, 1992

→Hober Annegret (ed.), Gabriele Münter, Munich, Prestel, 2003

→Gockerell Nina, Uhrig Sandra (eds.), Werner Constanze, Gabriele Münter und die Volkskunst : “Aber Glasbilder scheint mir, lernten wir erst hier kennen.”, exh. cat., Schloßmuseum Murnau, Murnau (27 July – 12 November 2017), Murnau, Schloßmuseum, 2017

→Jansen Isabelle & Mühling Matthias (dir.), Gabriele Münter 1877-1962. Painting to the Point, exh. cat., Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München (31 October 2017 – 8 April 2018), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk (3 May – 19 August 2018), Museum Ludwig, Cologne (15 September 2018 – 13 January 2019), Prestel, 2017

Gabriele Münter: The Search for Expression 1906-1917, The Courtauld Gallery, London, 2005

→Gabriele Münter, Une artiste du Cavalier Bleu, Musée des beaux-arts de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, 22 October 2004 – 23 January 2005

→Gabriele Münter, Lenbachhaus, Munich, 31 October 2017 – 8 April 2018

German painter and engraver.

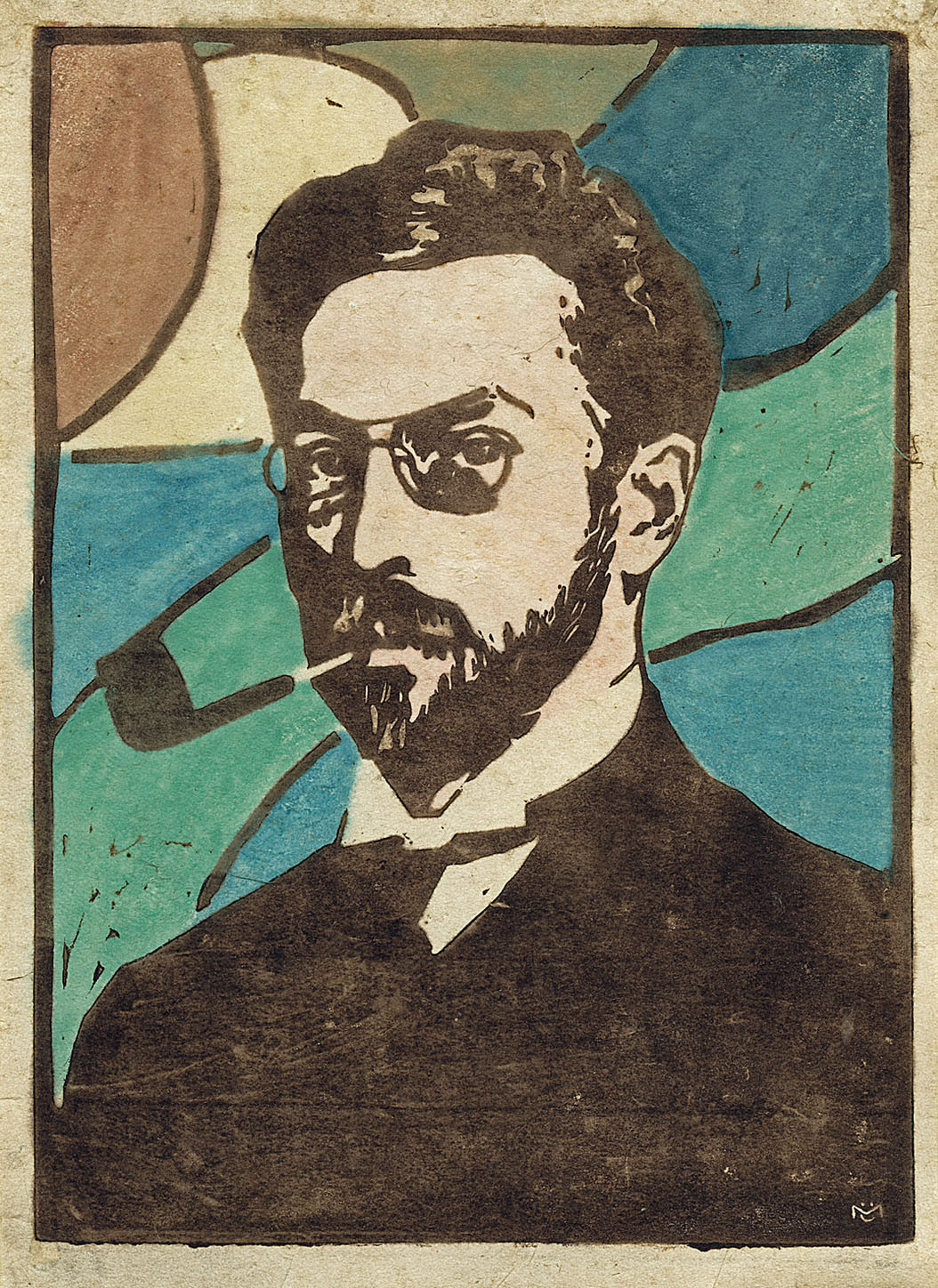

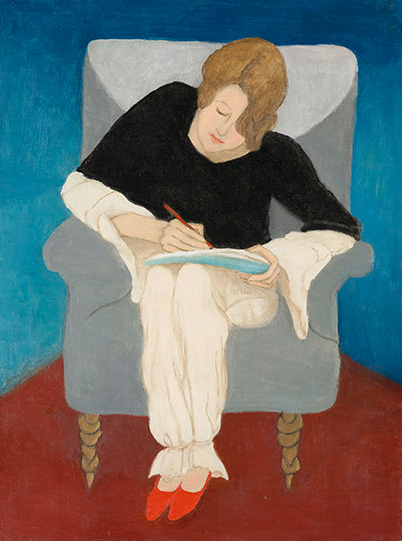

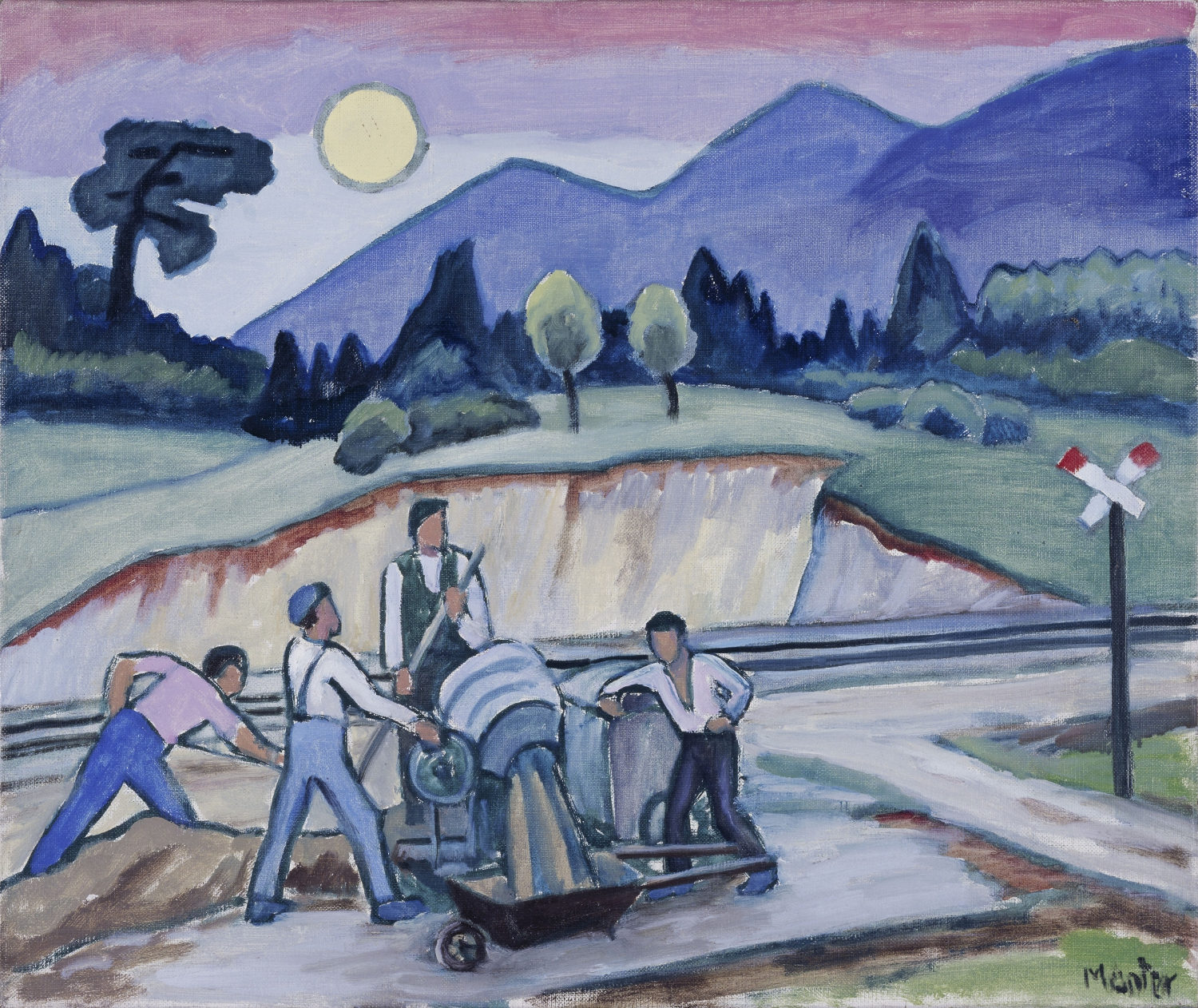

Born to an upper middle class protestant family, Gabriele Münter enrolled at the Malschule für Dame (“Ladies’ painting school”) in Düsseldorf in 1897. After spending two years in the United States, she moved back to Munich in 1901 to continue her artistic training and quickly gravitated toward the lessons provided by the new art association Phalanx. There, she learnt wood engraving with Ernst Neumann, sculpture with Wilhelm Hüsgen, and especially painting nudes with Wassily Kandinsky, with whom her personal relationship became official in 1902. The young woman began to paint outdoors – landscapes constructed in small touches applied with a knife in a limited number of colours (Kandinsky beim Landschaftmalen [“Kandinsky painting a landscape”], Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, 1903). The couple spent time travelling from 1902 to 1906 before settling in Sèvres, near Paris. Gabriele Münter started to gain recognition as an artist in her own right: her paintings were accepted at the Salon des Indépendants, her engravings at the Salon d’Automne, and a selection of her wood engravings was presented in the review Tendances nouvelles in 1906. Upon returning to Germany during the summer of 1908, the couple discovered the small town of Murnau, at the foot of the Bavarian Alps, which they would come to visit regularly with Alexei Jawlensky and his partner Marianne von Werefkin. In the many paintings she made of Murnau and its surroundings, Münter set aside impressionist touches and colours in favour of synthetic compositions made up of large, bold-coloured planes, with simple outlines and basic shapes often emphasised with black contours inherited from Paul Gauguin’s Cloisonnism, which Jawlensky introduced to his friends (Landschaft mit Weisser Mauer [“Landscape with White Wall”], Karl Ernst Osthaus-Museum, Hagen, 1910).

First a founding member of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (“new association of Munich painters”), she eventually created Der Blaue Reiter (“The Blue Rider”) with Kandinsky and Franz Marc, a group of artists which brought together partisans of the new German Expressionism. While staying in Murnau, where she bought a house dubbed the Maison des Russes, she became interested in Bavarian glass paintings. Inspired by their naïve and primitivistic style, the couple began to collect them and apply the technique to their own work. Later on, some of Münter’s landscapes and still lifes, such as Maske mit Rosa (“Black Mask with Rose”, 1912), show the influence of formalism, as practiced by Pablo Picasso, or of the German Expressionism of the group Die Brücke (“the bridge”). The merchant Herwarth Walden noticed her work and championed her: in 1913, she was the first Blaue Reiter artist to hold a personal exhibition at the Der Sturm gallery. Living in exile during the war and separated from Kandinsky, who moved back to Russia in 1915, she faced hard times upon returning to Germany in 1920. She finally moved back to Murnau permanently in 1930 with her new partner, the art historian Johannes Eichner, and spent the rest of her life reprising subjects she had painted in the 1910s. In 1957, she donated 25 of Kandinsky’s early works and several of her own to the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus in Munich. While she had remained in Kandinsky’s shadow for a long time, her work was finally rewarded with a major retrospective in 1992, which highlighted the essential role she played in the birth of Modern Art in Germany.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Gabriele Münter : femme, peintre et photographe

Gabriele Münter : femme, peintre et photographe