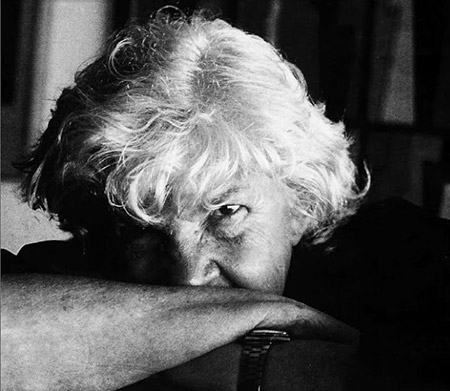

Gail Tremblay

Schwain, Kristin, Steeley, Josephine, Rooted, Revived, and Reinvented: Basketry in America, exh. cat., Whatcom Museum, Bellingham (3 February–6 May, 2018), Atglen, Schiffer Publishing, 2017, p. 68-69

→Vigil, Jennifer, “Gail Tremblay,” in Mithlo, Nancy Marie (ed.), Manifestations: New Native Art Criticism, Santa Fe, Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, 2011, p. 178-179

→Matilsky, Barbara (ed.), Show Of Hands: Northwest Women Artists, 1880-2010, exh. cat., Whatcom Museum, Bellingham, (24 April–8 August, 2010), Bellingham, Whatcom Museum, 2010, p. 33

Gail Tremblay: Fiber, Metal, Wood, Museum of the Plains Indian, Browning, 1988

→Gail Tremblay: Twenty Years of Making, Sacred Circles Gallery, Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center, Seattle, 31 May–28 July, 2002

→Re-Imagining Film Images of American Indians, Froelick Gallery, Portland, 27 February–31 March, 2018

Re-Imagining Film Images of American Indians, Froelick Gallery, Portland, 27 février – 31 mars 2018

Gail Tremblay: Twenty Years of Making, Sacred Circles Gallery, Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center, Seattle, 31 May–28 July, 2002

Gail Tremblay: Twenty Years of Making, Sacred Circles Gallery, Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center, Seattle, 31 mai – 28 juillet 2002

Gail Tremblay: Fiber, Metal, Wood, Museum of the Plains Indian, Browning, 1988

American mixed-media artist, poet and educator.

Gail Tremblay was born in Buffalo, New York. She earned a Bachelor of Arts in theatre from the University of New Hampshire in 1967 and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from the University of Oregon, Eugene in 1969. From 1980 to 2018, G. Tremblay taught classes in visual arts, creative writing and Native American studies at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. Throughout her life, she claimed to have Mi’kmaq and Onondaga ancestry but she herself was never an enrolled member of any Indigenous Nation. Additionally, she was never certified by any Indigenous Nation as a non-enrolled Native American artisan. Despite questions surrounding her Native American ancestry, many Native artists and institutions with significant Native American art collections have embraced her work. She began showing her works in group and solo exhibitions in the late 1960s and was a prolific writer on contemporary Native American art.

Throughout the course of her four-decade long career, G. Tremblay crafted innovative baskets inspired by the weaving techniques of eastern woodland Indigenous peoples, particularly those of the Haudenosaunee. Instead of using traditional materials such as strips of ash bark and sweetgrass, G. Tremblay utilized film strips from both ethnographic and popular movies from the 20th century. She largely drew on films depicting Native American life that were created by Euro-American filmmakers. Historically, the medium of film has often been used by Euro-Americans to exploit and perpetuate harmful stereotypes of Native Americans. By repurposing such material into Indigenous techniques of basketweaving, G. Tremblay powerfully critiques Euro-Americans’ often harmful fascination with Indigenous Americans. One such work is When Ice Stretched On For Miles (2017), which uses film strips from an ethnographic documentary, At the Winter Sea Ice Camp (1967), about a Netsilik Inuit family. The piece points out the irony of Euro-American anthropologists’ fascination with traditional Indigenous ways of life while simultaneously celebrating supposed modernisation that too often led to the exploitation of both Indigenous peoples and their land. Other similar works include It Was Never About Playing Cowboys and Indians (2012), which uses film stock that depicts Native American children doing beadwork. The piece celebrates the ways in which young Indigenous people have continued to preserve traditions and cultural lifeways. Other works such as And Then There is the Hollywood Indian Princess (2002), directly address the gendered ways popular film has stereotyped Native American women. In addition to her popular film baskets, G. Tremblay also created installations such as Waiting for the Return: 5 Fish Traps (2002) and paintings like All That Glitters… (2010).

Over the course of her career, G. Tremblay crafted unique weaving works that braided together unexpected mediums. Her work not only challenged traditional basket weaving techniques but also critiqued the portrayal of Native Americans on screen. G. Tremblay’s art pieces are part of the permanent collections of such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C., the Brooklyn Museum, New York and the Denver Art Museum, Denver.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2024