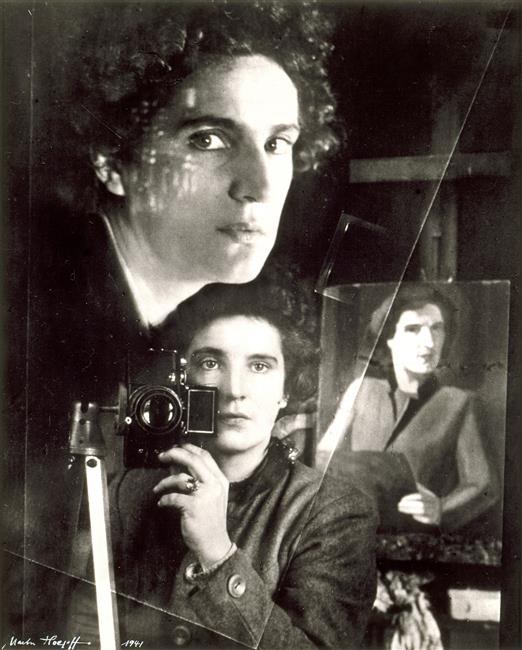

Germaine Casse

Lozère, Christelle, “Artists from the Antilles in Interwar Paris”, exhibition catalogue The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, Murrell, Denise (dir.), New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2024, p. 76-82

→Lozère, Christelle, Histoire de l’art des Antilles françaises en contexte esclavagiste et post-esclavagiste (XIXe siècle–1943). Pratiques, réseaux et échanges artistiques, habilitation thesis, Université Panthéon Sorbonne, 27 June 2023, p. 209-219

→Lozère, Christelle, “Germaine Casse et la mission de 1923 en Guadeloupe : un mirage politique ?”, Houssais, Laurent and Jarrassé, Dominique (dir.), Nos artistes aux colonies, Sociétés, expositions et revues dans l’empire français 1851–1940, Paris, Éditions Esthétiques du Divers, 2015, p.140-157

Ier Salon de la Société des artistes antillais, Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, 15–31 January 1924

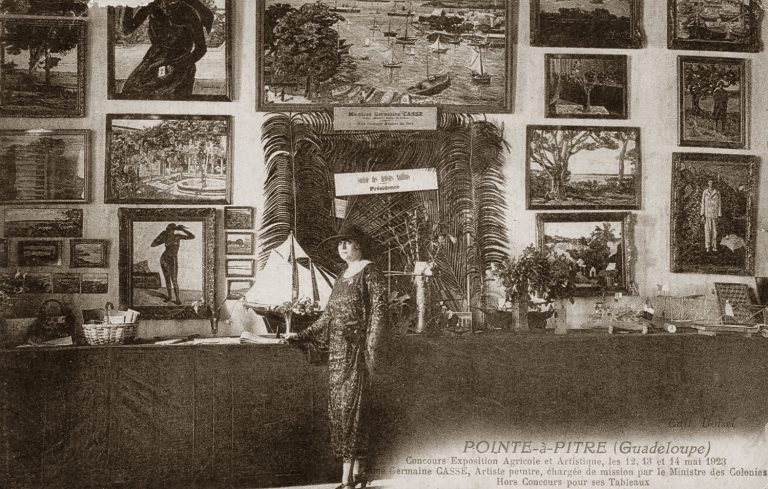

→Exposition Germaine Casse, Agricultural and artistic exhibition competition at Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe, 12–14 May 1923

→Antilles, Outre-Mer. Exposition Germaine Casse, Musée de la France d’Outre-Mer, Palais de la Porte dorée, Paris, 6–18 November 1957

Guadeloupean painter and theatre designer.

Julie Élise Germaine Casse was the daughter of Germain Casse, a Guadeloupean white Creole, fervent Schœlcherist and member of parliament for the radical left wing party, and Julie John, a woman of Senegalese origins. G. Casse’s grandmother, Marie John, was of mixed heritage, born to a British officer father and a Fula mother. Her father was governor of Martinique for a period, and later treasurer-paymaster in Guadeloupe, so G. Casse spent the period between the ages of nine and thirteen in the Antilles before moving with her parents to the south of France. She was a student at the Avignon École des beaux-arts and studied for ten years under Pierre Grivolas (1823–1906), who trained her in the post-impressionist shifting lights and colours of plein-air painting.

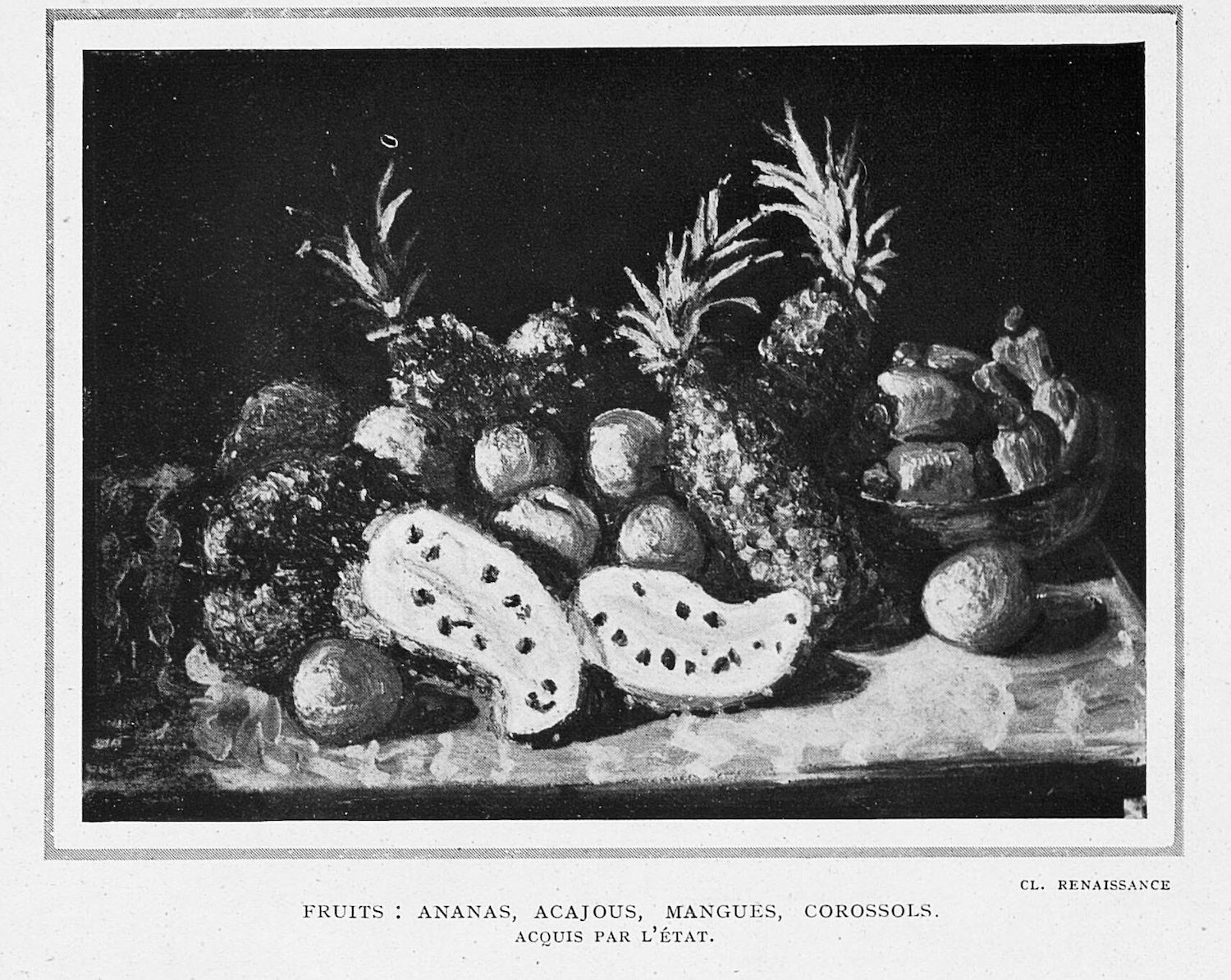

For a long time G. Casse would remain in the shadow of her husband, the sculptor Jean-Pierre Gras (1879–1964), and only embarked on her artistic career at the age of thirty-nine, following their divorce. It was her friend Jeanne de Flandreysy, a patron of Félibrige [Occitan] artists, who encouraged her to reconnect with her Antillean roots. In 1920 at the Salon de la Société nationale des beaux-arts she was awarded a colonial travel grant, and as her destination she chose Guadeloupe. Her Avignon and Guadeloupe works were a success at the 1922 Colonial Exhibition in Marseille, and the Ministry of Colonies accepted her request for a two-year artistic mission to Guadeloupe. In May 1923, she presented her works in an exhibition in Pointe-à-Pitre, and in January 1924 founded the Société des artistes antillais with Henry Gabriel (dates?), a professor of drawing from Haiti, and Gilbert de Chambertrand (1890–1983), a Guadeloupean writer and draughtsman. Intended as an ‘Antillean Villa Medici’, the poster for the Society’s first salon in 1924 is an allegorical manifesto for the excellence of Black women across all forms of art: painting, sculpture, music and literature.

Upon her return to Paris in 1924, G. Casse presented her Guadeloupe paintings to the general public at the Salon d’Automne and the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. As a close friend of Henry Bérenger, the Guadeloupe senator, French ambassador to the United States and president of the Société coloniale des artistes français, she soon obtained the support of the Black political elite in France, notably that of Gratien Candace, member of parliament for Guadeloupe. In August 1925, the Galerie Georges Petit mounted an exhibition devoted entirely to her work. The painting chosen to illustrate the catalogue’s cover was Édoualine, portrait de jeune fille [Édoualine, portrait of a young girl], showing a young Guadeloupean girl with a slightly worried expression, a large madras scarf wound round her head. G. Casse’s Portrait de M. Alidor Dorvil, conseiller municipal de Petit-Bourg [Portrait of M. Alidor Dorvil, Petit-Bourg town councillor] and Mimi likewise depict and deliberately name the Guadeloupean men and women in her entourage of family and friends. As early as 1923 Alain Locke, principal theorist of the Harlem Renaissance and pioneer of the New Negro philosophy, noted in Opportunity magazine the emerging significance of G. Casse in France as part of the new treatment of Black representation.

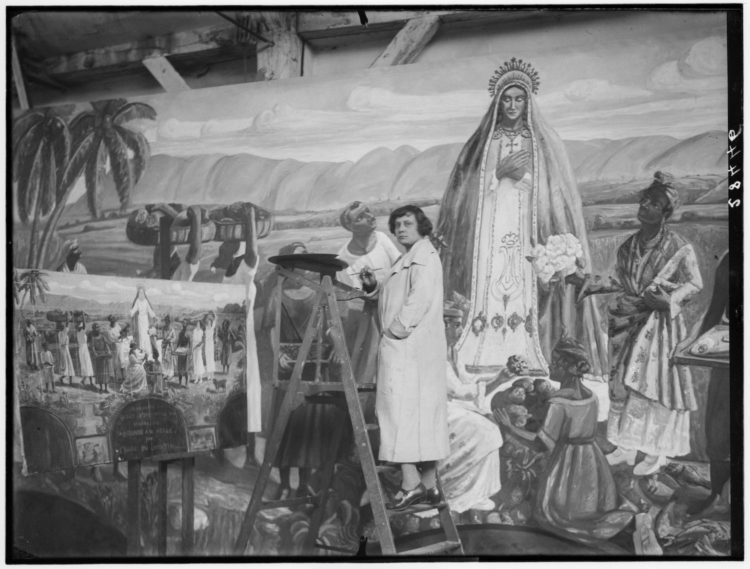

In 1925, G. Casse set up the Karukéra workshop in her Paris residence, receiving and supporting figures of the nascent Afro-Caribbean performing arts scene, then relatively unknown, including Moune de Rivel, Jenny Alpha, Rama-Tahé and Darling Légitimus. As a member of the board of La Solidarité antillaise, she designed so-called ‘Antillean’ sets for cabaret and theatre productions, notably for Victor Étienne Légitimus. Awarded the rank of Chevalière de la Légion d’honneur, G. Casse took part in the major colonial exhibitions of her time: Rome (1931), Brussels (1935), Naples (1934–1935), the Tricentenaire du rattachement des Antilles à la France (1935–1936) and New York (1939–1940).

Towards the end of her life, the assimilationist and colonialist discourses set forth by G. Casse would engender a rift with the young Afro-Caribbean artists who were then positioning themselves within the Négritude movement. Following the Second World War the artist was marginalised, despite the fervent support of the Amis d’Avignon association and of Moune de Rivel and Jenny Alpha, who penned articles describing her pioneering and influential role during the 1920s. A retrospective exhibition was held at the Musée de la France d’outre-mer in Paris between 6 and 18 November, 1957. In 1967, G. Casse died aged 86 in poverty and obscurity.