Focus

Loïs Mailou Jones, Untitled (Two Women), c. 1945, the Baltimore Museum of Art: Purchase with exchange funds from the Pearlstone Family Fund and partial gift of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., BMA 2020.98, © Loïs Mailou Jones Pierre-Noel Trust

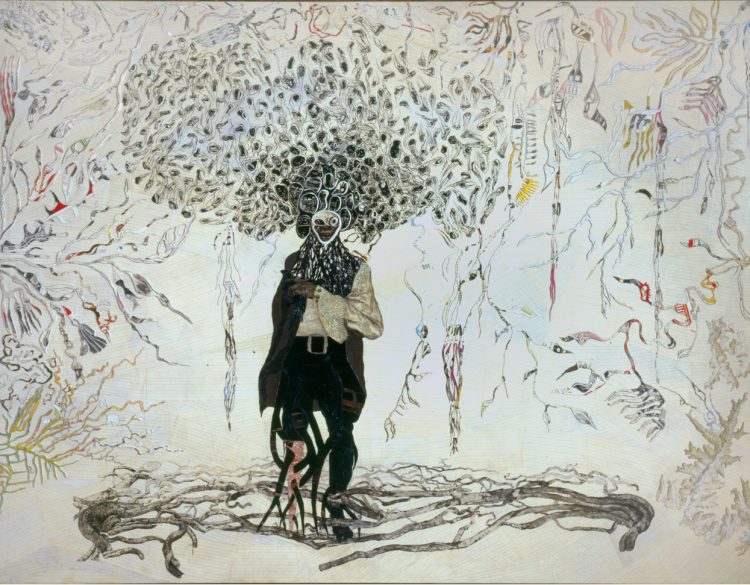

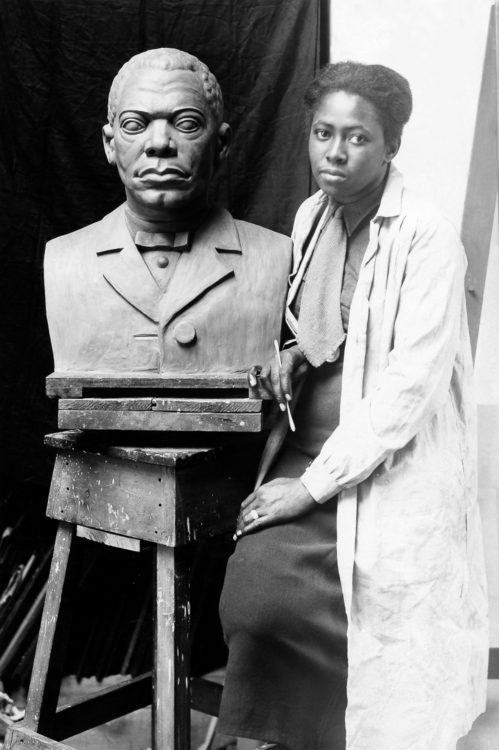

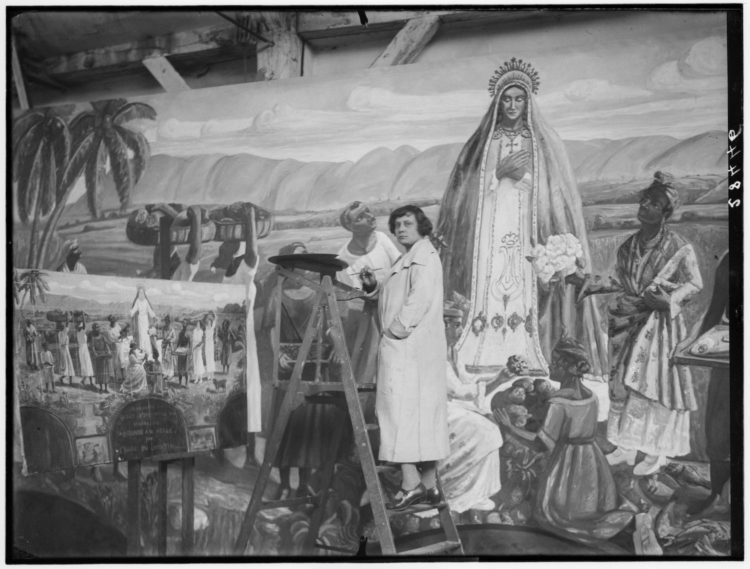

Touching upon every aspect of artistic creativity, the Harlem Renaissance, also known as the New Negro movement – was an African American cultural movement embracing the literary, musical, theatrical and visual arts, that largely took place from the 1920s with the Great Migration, through the mid- to late 1930s and early 1940s, fading away with the Great Depression. The recent exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, organised by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met), in New York, from 25 February to 28 July 2024, explored this significant moment in early twentieth-century African American art and culture and offers a timely opportunity for re-examining the works of its long-overlooked artists. In the field of visual arts, African American women artists featured in the Met show included sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1887–1968), painter Laura Wheeler Waring (1887–1948), sculptor Augusta Savage (1892–1962), painter Loïs Mailou Jones (1905- 1998) and sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012).

The art of the Harlem Renaissance was not defined by a unified stylistic standard amongst the figures, but the work by those women artists commonly associated with the movement found echoes in the prescriptions of theorist and philosopher Alain Locke in his anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925). In this manifesto, A. Locke urged African American artists to produce work that reflected self-pride and to use the aesthetic designs of African art as cultural references and guidance for their work. Because Black people had been caricatured and stereotyped in American visual culture and literature, African American artists were encouraged to engage in portrayals of Black people and lives that would counteract demeaning and negative imagery.

As suggested by the Met exhibition title, the Harlem Renaissance was not confined to the neighbourhood of Harlem in New York, but spread across and beyond the United States, in cities nationwide and overseas. For African Americans artists, writers and musicians, France represented a place to fulfil their artistic dreams and a refuge from racial discrimination in the United States. Many women artists of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Selma Hortense Burke (1900–1995) and Nancy Elizabeth Prophet (1890–1960), expanded their experience and knowledge in Paris, often studying in fine art schools with renowned professors, visiting art collections or exhibitions that impacted their work, exhibiting in salons and art galleries, mingling with people from everywhere, or receiving the support and advice of Black artist expatriates living in the capital.

A focus produced as part of “The Origin of Others. Rewriting Art History in the Americas, 19th Century – Today” research programme, in partnership with the Clark Art Institute.

1877 — 1968 | United States

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller

1892 — 1962 | United States

Augusta Savage

1915 — United States | 2012 — Mexico

Elizabeth Catlett

1900 — 1995 | United States

Selma Hortense Burke

1905 — 1998 | United States

Lois Mailou Jones

1887 — 1948 | United States

Laura Wheeler Waring

1881 — 1967 | France

Germaine Casse

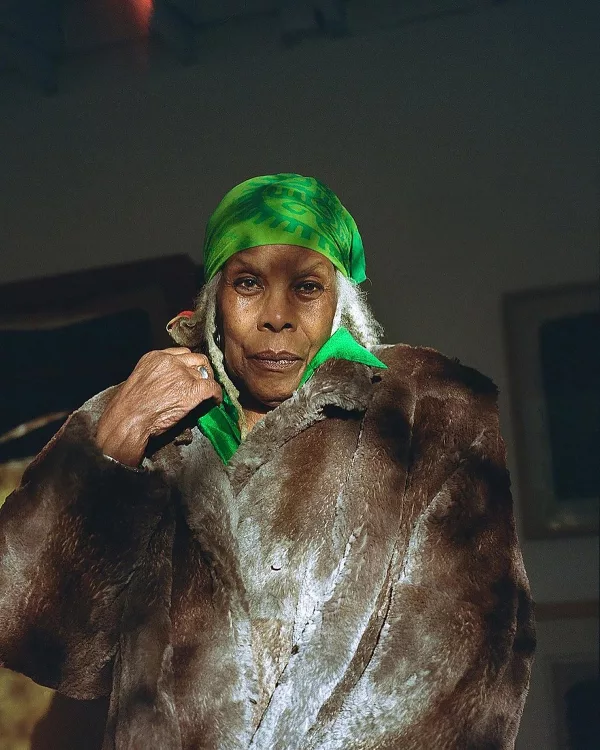

1942 | United States

Mary Lovelace O’Neal

1915 — 2010 | United States

Margaret Taylor Goss Burroughs

1885 — 1952 |

Suzanna Ogunjami

Racism and art in the United States

Rewriting Memories and Denouncing History: Postcolonial Art

Tous droits réservés dans tous pays/All rights reserved for all countries.