Research

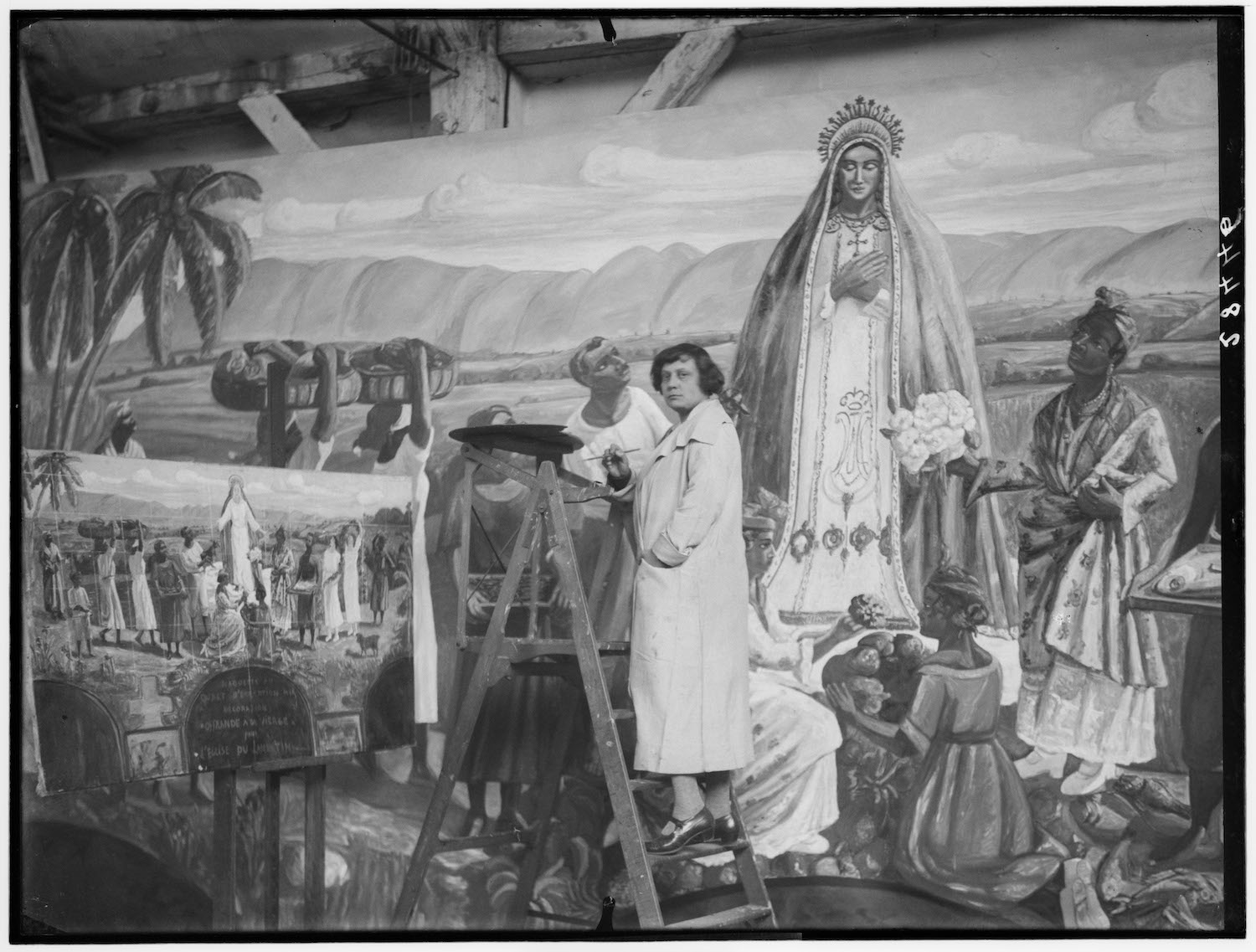

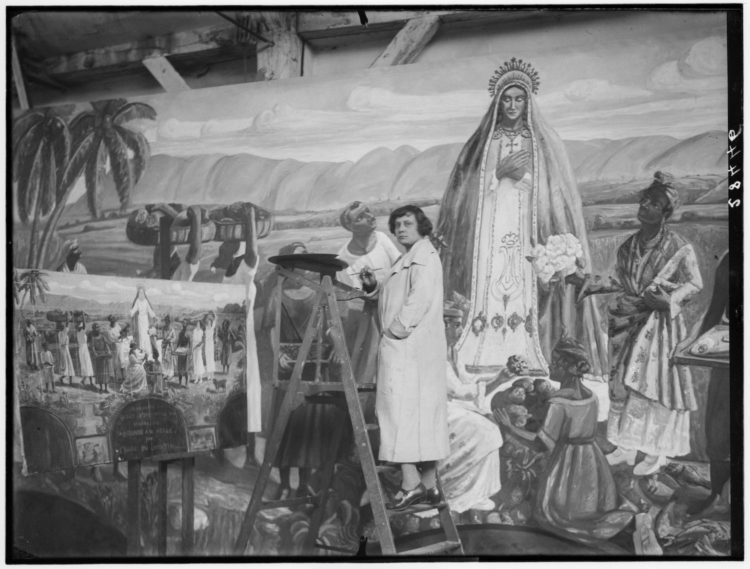

Germaine Casse working in her atelier, photograph taken by François Antoine Vizzavona. © Ministère de la Culture – Médiathèque du patrimoine et de la photographie, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Franck Raux

The vogue for artistic education and the decorative arts that gripped the French aristocracy and middle class in the 1780s gave rise to the presence of women in ateliers of ‘demoiselles’, where they were taught by renowned artists. Yet the lack of an art academy in Guadeloupe and Martinique meant that young people wanting to study fine art were forced to leave the colonies for metropolitan France. This migration out of the Caribbean reinforced the cultural elitism of colonial slave society, because only legally free and socially privileged individuals could undertake such a journey of training and learning and go on to make a living from their artistic practices.1

Jenny Prinssay, View of a bay on the island of Martinique, 1814, oil on canvas, 25.2 x 34.2 in., 64.1 cm x 86.9 cm

Jenny Prinssay, View of Martinique, undated, oil on panel, 11 x 15.7 in., 28 x 40 cm, Musée du Nouveau Monde de La Rochelle.

Jenny Prinssay, View of Guadeloupe, 1813, oil on canvas, 12.9 x 17 in., 33 x 43.4 cm, Musée du Nouveau Monde de La Rochelle.

In Paris, the first woman painter native to the French Antilles may have moved in the circles of Guillaume Lethière (1760–1832), a Guadeloupean artist who led a women’s atelier. Jeanne Pauline Bouscaren (born 1771), known by her married name of Jenny Prinssay, is one of the rare women whose artistic practice was recognised by the Salons. She was born into the Bouscaren family, owner-occupants of their land since settling in Guadeloupe and Martinique in the eighteenth century, and baptised in Goyave. Under the Napoleonic Empire, her Vues de la Guadeloupe and Vues de la Martinique paved the way for a school of Caribbean picturesque landscape painting. In Martinique, a collection of forty-one drawings by young girls at the Saint-Pierre boarding school from 1840 to 1843 testifies to the importance of drawing instruction in the education of primary schoolgirls. By the end of the nineteenth century, two other women painters, both portraitists, had likewise distinguished themselves at the Salon: the Martinican Inès de Beaufond (born about 1850, active between 1880 and 1900) and the Guadeloupean Clotilde Marie Geneviève Fournier (born 1869).

A long struggle for the ‘de-racialisation’ and the feminisation of artistic practices

Although the first women artists native to the French Antilles were mainly born into the white elite, Afro-Caribbean women artists were not entirely absent from the official art of the nineteenth century. Even so, access to fine arts training remained complicated and heavily influenced by racial prejudice. In Guadeloupe and Martinique, before the abolition of slavery in 1848, black children were banned from taking drawing classes in both private ateliers and primary schools. Pressure was exerted on the islands’ artists, who were dependent on wealthy people for commissioned work, to uphold the ban. Jules Ferry’s reform of the state school system during the Third Republic enabled a slow democratisation and ‘de-racialisation’ of artistic practices on the islands, with the recruitment of art teachers loyal to the Republic in Guadeloupean and Martinican lycées. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the first young women of the “bourgeoisie de couleur” began their training. As for many other women at the time, gaining acceptance into French fine arts schools was difficult. In 1893, Gaston Gerville-Réache, member of parliament for Guadeloupe, became one of the rare politicians to speak out in parliament in favour of the admission of women into the École nationale des beaux-arts.2 Thus the miniaturist Marguerite-Marie Télèphe (born 1870), a member of the “bourgeoisie de couleur”, was able to establish herself in Paris, in the Batignolles neighbourhood. She studied under Mme Latruffe-Colomb, director of a free drawing class subsidised by the city council, and her name is attached to a frame containing three miniatures (portraits) of Creole people completed in 1893. In Martinique, Charlotte Tavi (dates?), a drawing teacher at the Pensionnat colonial de jeunes filles de Saint-Pierre in 1897, would encourage her daughter Alice (1871–1971) to establish herself as an artist by attending the École des beaux-arts de Paris. Returning to Martinique, in 1899 Alice Albane (her married name) became the first woman of African descent to be certified professor of drawing at the same school. Throughout her career, alongside fellow politically engaged women teachers, she would train the future artistic and intellectual elite of Martinique: the Debuc sisters, Nardal, Marie-Thérèse Julien Lung-Fou (1909–1981) and Suzanne Roussi, who would later marry Aimé Césaire.

But it was during the interwar period that women began to play a decisive role in the construction of an assimilationist Antillais imaginarium. In 1925, Henry Bérenger, a Guadeloupean senator, was nominated head of the Société coloniale des artistes français (SCAF), leading to a rise in the popularity of Antillais subjects. He would appoint two women to the management committee, a first, along with the first black man, Guadeloupean member of parliament Gratien Candace. The participation of several European and Caribbean women artists, including painters, sculptors and musicians, in the construction of a post-slavery imaginarium, now imbued with the ‘beaux-arts’ aesthetic, contributed to a growing regard for a feminine black Antillais and Guyanese beauty. Simultaneously, a counterpart was created: a new colonial imaginarium forged in Paris, seen by its detractors as exoticising, elitist and disconnected from the islands’ social realities.

Germaine Casse, Poster of the First Salon of the Société des artistes antillais, which took place in Pointe-à-Pitre (Guadeloupe) from January 15th to 31st, 1924, 120 x 80 cm

Germaine Casse, Mimi, undated, artwork reproduced in the chapter “La Guadeloupe illustrée par Germaine Casse” of the book La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, printed in Paris in 1922

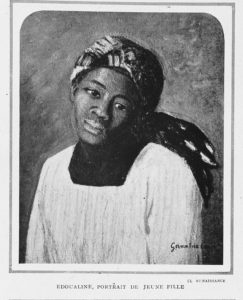

Germaine Casse, Édoualine, portrait de jeune fille, undated, artwork reproduced in the chapter “La Guadeloupe illustrée par Germaine Casse” of the book La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, printed in Paris in 1922

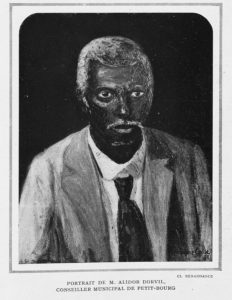

Germaine Casse, Portrait de M. Alidor Dorvil, conseiller municipal de Petit-Bourg, 1921. Artwork reproduced in the chapter “La Guadeloupe illustrée par Germaine Casse” of the book La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, printed in Paris in 1922.

Germaine Casse (1881–1967), a figurehead of the Antillais School in Paris

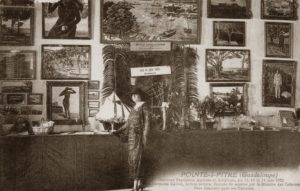

Germaine Casse was born in Paris, the daughter of member of parliament for Guadeloupe Germain Casse, a fervent abolitionist and republican, and Julie John, a woman of Senegalese origin. Her grandmother, Marie John, was the daughter of a British officer and a Fula woman. She appears to have spent her childhood in the Antilles from 1889, when her father arrived from metropolitan France having been appointed Governor of Martinique, later becoming Treasurer-Paymaster General of Guadeloupe in 1890. As part of a mission financed by the SCAF, the artist created a Société des artistes antillais in 1924 in Pointe-à-Pitre, with the aim of bringing modern art to the two “vieilles colonies”. The society’s poster was a call to Black women to excel in all forms of art: painting, sculpture, music and literature. G. Casse’s return to Paris provided an opportunity to publicly exhibit the one hundred and forty-five paintings that she had produced in Guadeloupe. In August 1925, an exhibition sponsored by the Ministry of Colonies was devoted to her at the Galerie Georges Petit. The painting Édoualine, the portrait of a young girl that was chosen to illustrate the catalogue, shows a young Guadeloupean with her hair wrapped in a large Madras scarf. Her tilted head and slightly twisted body give the composition a dynamic effect. The brushstrokes are wide and spontaneous, as if the portrait had been painted on the spur of the moment. G. Casse’s decision to identify her model by specifying her first name, Édoualine, suggests a closeness with the young girl. In a similar way, the Portrait de M. Alidor Dorvil, conseiller municipal de Petit-Bourg or Mimi show the faces of Antillais men and women in the painter’s entourage who are deliberately named and humanised.

Stand of Germaine Casse at the Agricultural and Artistic Exhibition Contest of Pointe-à-Pitre (Guadeloupe), held from May 12th to 14th, 1923.

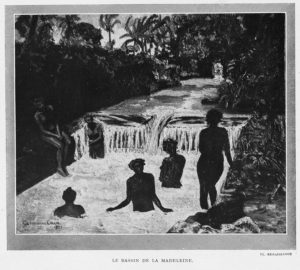

Germaine Casse, Le bassin de la Madeleine, 1921, artwork reproduced in the chapter “La Guadeloupe illustrée par Germaine Casse” of the book La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, printed in Paris in 1922

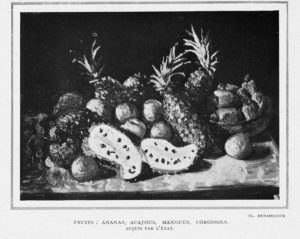

Germaine Casse, Fruits : Ananas, acajous, mangues, corossols, undated. Artwork reproduced in the chapter “La Guadeloupe illustrée par Germaine Casse” of the book La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, printed in Paris in 1922.

As early as 1923, Alain Locke, a leading theorist of the Harlem Renaissance3 and ambassador of the New Negro aesthetic, writing in the journal Opportunity, identified the nascent contribution of G. Casse to a new treatment in the representation of Black people.4A. Locke underlined “the gradual outgrowing of the casual interest, either of the exotic or the genre sort” visible in the work of certain European artists, citing G. Casse as part of the “development of a matured and sustained interest” in the representation of Black people. In 1928, a laudatory article in the journal The Afro American of Baltimore spoke of the “black blood” running in the artist’s veins, testifying to this period during which the visual representation of Black people was a subject of debate in the United States. However, the assimilationist and colonial discourse proposed by G. Casse dissociated her from the militant and politically engaged activities of African-American artists, and from the Négritude. In 1940, her name was cited once again by historian Joel Augustus Rogers as being one of the Black and personalities of African descent to have left their mark on the history of France.5

Marie-Thérèse Julien Lung-Fou, L’Offrande, 1938, plaster © Lung-Fou Family

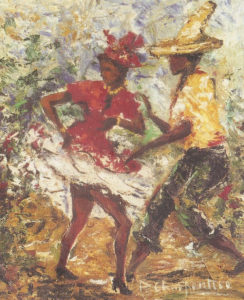

Paule Charpentier, Bèlè, Courtesy of the Charpentier Family

Towards the first Black women-owned ateliers in Martinique

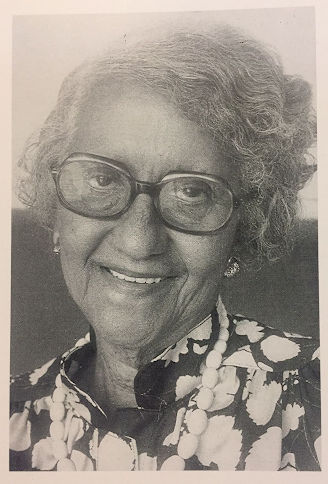

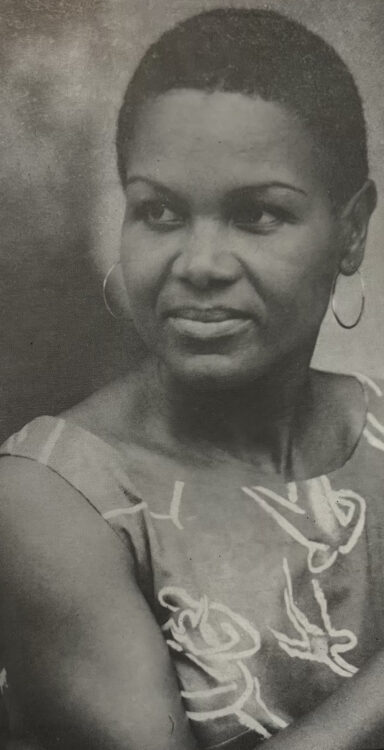

It was also during the interwar period that the careers of Martinican artists Paule Charpentier (1910–2004) and M.-T. Julien Lung-Fou first took off. From the Second World War on, art in the French Antilles conceptualised itself in terms of rupture, and the contesting and rejection of the Western model and of colonial art, along with the affirmation of Négritude. This aesthetic and thematic rebellion expressed itself in Afro-Caribbean artists’ desire to reappropriate their African cultural identity. A prolific artist from the black bourgeoisie of Fort-de-France, P. Charpentier, née Jacques Joseph, sought to represent the essence of Antillais culture through her work. Between 1945 and 1950, she owned two galleries with her husband, Hector. For her part, M.-T. Julien Lung-Fou was born in Trois-Îlets. Her origins were French, Black Martinican through her grandmothers and Chinese. She attended the Pensionnat colonial de Fort-de-France before leaving in 1934, rather late for financial reasons, to study at the École nationale des beaux-arts de Paris, becoming the first woman sculptor of the French Antilles. Though talented, she remained at the margins of the colonial artists’ salons, a situation that hindered her national career. From the 1950s, in her studio situated on the Route de Didier, in Fort-de-France, she trained young artists, particularly women, in sculpture, ceramics and painting. Founder and president of the Salon des réalités martiniquaises from 1952 until 1959, and the inspiration for the journal Dialogue, she energetically steered the Groupement des artistes Martiniquais, which would itself author a manifesto for the Black Caribbean world that celebrated multiculturalism, cross-cultural dialogue and equality between all peoples.

Christelle Lozère, Histoire de l’art des Antilles françaises en contexte esclavagiste et post-esclavagiste (XIXe siècle-1943). Pratiques, réseaux et échanges artistiques, habilitation thesis, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2023, 434 p.

2

Journal officiel de la République française. Débats parlementaires. Chambres des députés, compte rendu, 15 February 1895, p. 346.

3

Denise Murrell (dir.), The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic, exh. cat., New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, London, Yale University Press, 2024.

4

Alain Locke, “More of the Negro in Art”, Opportunity, vol. 3-4, 1923, p. 363.

5

Joel Augustus Rogers, Sex and Race. Negro-Caucasian Mixing in All Ages and All Lands. The Old World, vol. 2, 1940.

Christelle Lozère is an associate professor of Art History at the University of the Antilles, and co-director of the FRACA team (UMR PHEEAC, formerly LC2S). For the past ten years, her research has focused on the history of art in the French Antilles and the Caribbean in the context of slavery, post-slavery and colonialism. Winner of the Musée d’Orsay Prize, she has been a guest scholar at the INHA, the Clark Art Institute and the Villa Vassilieff (AWARE). In 2024, she is currently a visiting researcher at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac.