Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie

Goeman, Mishuana R., “Disrupting a Settler-Colonial Grammar of Place: The Visual Memoir of Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie”, in Simpson, Audra and Smith, Andrea (eds.), Theorizing Native Studies, Durham, Duke University Press, 2014, p. 235-265

→Tsinhnahjinnie, Hulleah J. and Passalacqua, Veronica (eds.), Our People, Our Land, Our Images: International Indigenous Photographers, Berkeley, Heyday Books, 2007

→Tsinhnahjinnie, Hulleah J., “Visual Sovereignty: A Continuous Aboriginal/Indigenous Landscape”, in Nottage, James H. (ed.), Diversity and Dialogue, Seattle, WA, University of Washington Press, 2007, p. 15-23

Kill the Man, Save the Indian, FotoArt Festival, Bielsko, October 16–31, 2009

→Against Amnesia: Hulleah Tsinhnhjinnie, Mois de la Photo, Dazibao, Montreal, September 8–October 8, 2005

→Photographic Memoirs of an Aboriginal Savant, Gorman Museum of Native American Art, Davis, November 13–December 23, 1994

American, Seminole, Muscogee, Diné (Navajo) photographer.

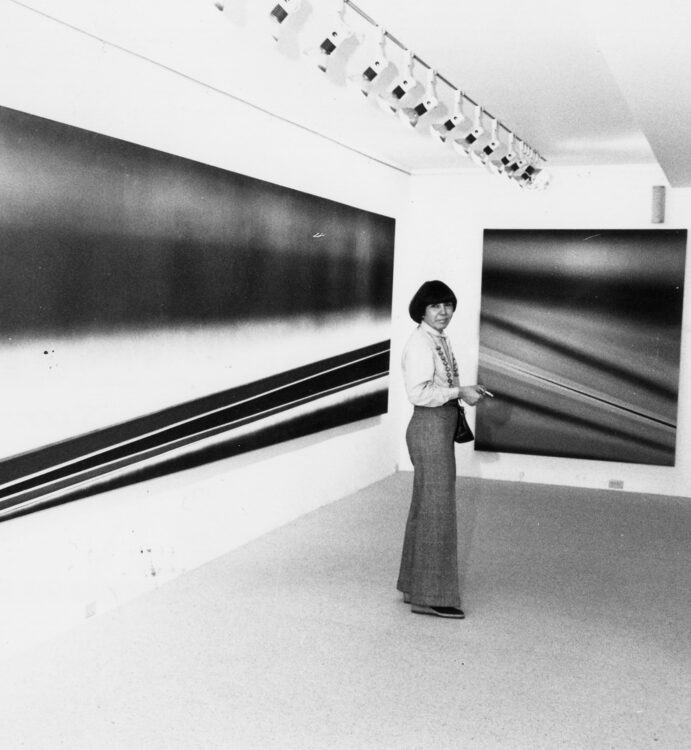

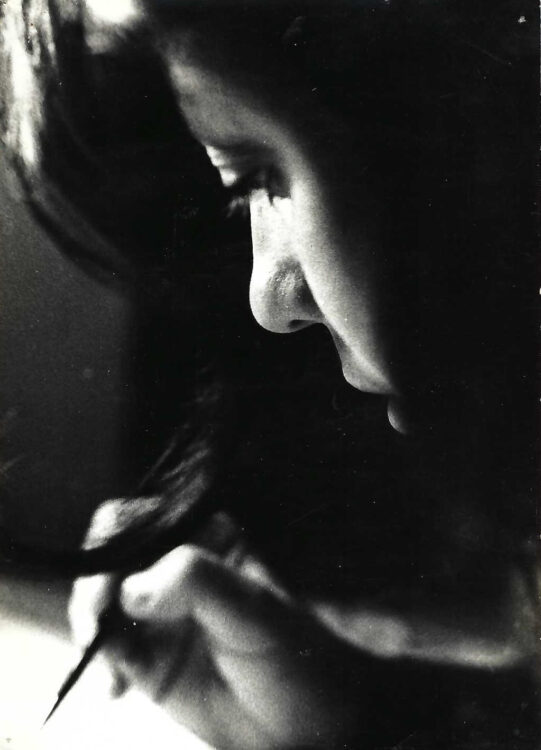

Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie is an accomplished multi-media artist who is best known for her photographic work rooted in visual Native American sovereignty. She was born into the Bear clan of the Taskigi Nation and the Tsinhnahjinnie clan of the Diné (Navajo) Nation. She grew up in both Phoenix and Rough Rock, Arizona. Her father, Andrew Van Tsinhnahjinnie (1916–2000), was a muralist and painter. As a result, she was exposed to art at an early age and was encouraged to become an artist herself. She attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, before moving to Oakland, California, where she earned her BFA from the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1981. In 2002, she earned her MFA from the University of California, Davis.

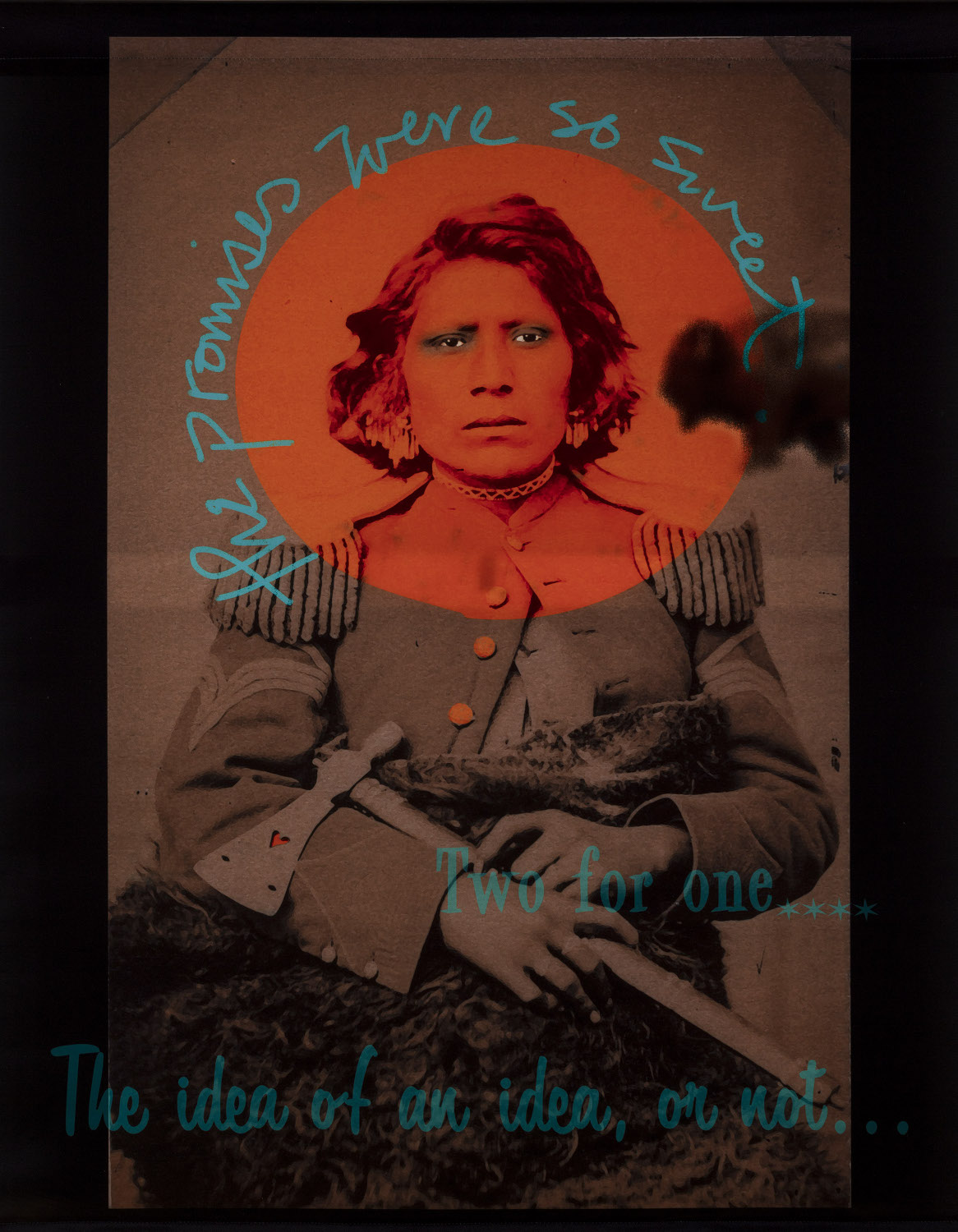

H. Tsinhnahjinnie was formally trained in both painting and photography. As a teenager, she was deeply inspired by Ernest Cole’s (1940–1990) photographs of Apartheid South Africa and realised the political possibilities of the medium. Through E. Cole’s photographs, she began to make connections between various international manifestations of settler colonialism, which marked a turning point for both her political and artistic awakening. H. Tsinhnahjinnie utilises both original photographs and retooled historical photographs of Indigenous peoples. Her photographs are meant for the Native American gaze and serve as a tool of historic and contemporary reclamation. To make her pieces unforgettable, the artist frequently uses humour, hand-tint and collage in her artworks. Vanna Brown, Azteca Style (1990), a part of the artist’s Native Television series (1990), imagines the popular masses witnessing Indigenous beauty from the lens of a Native American creator rather than from the white or “settler” perspective.

Later in her career, the artist recycled family photographs or appropriated images taken by white ethnographers and reconstructed them through collage. In her Portraits Against Amnesia series (2003), the artist took postcard-sized images, enlarged them and digitally manipulated them to assert her subjects’ presence to the viewer. Both Grandma (2003) and Idealia (2003) are part of that series. The artist applied a similar technique with Today I Was Thinking… (2010), which honours the memory and survival of non-humans, the Bison/Buffalo Nation. Throughout her career, H. Tsinhnahjinnie has taken control of the camera to assert an Indigenous point of view that sheds light on popular culture, memory and new ways of looking at the world around us.

Since 2004, H. Tsinhnahjinnie has served as the director of the Gorman Museum of Native American Art and an assistant professor in Native American Studies at the University of California, Davis. Her works are in the permanent collections of such institutions as the Museum of Modern Art, New York and the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023