Irma Stern

Dubow Neville, Irma Stern, South African Art Library, Cape Town, 1974

→Arnold Marion and Schmahmann Brenda (eds.), Between Union and Liberation: Women Artists in South Africa 1910-1994, Ashgate Publishing, 2005

→Braune Claudia B., “Beyond Black and White: Rethinking Irma Stern”, Focus, No. 61, Helen Suzman Foundation, Johannesburg, 2011

An Exhibition of Modern Art by Miss Irma Stern, Ashbey’s Gallery, Cape Town, 7 February – 21 February 1922

→Irma Stern und der Expressionismus: Afrika und Europa: Bilder und Zeichnungen bis 1945, Kunsthalle Bielefeld, 5 December 1996 – 09 February 1997

South African painter.

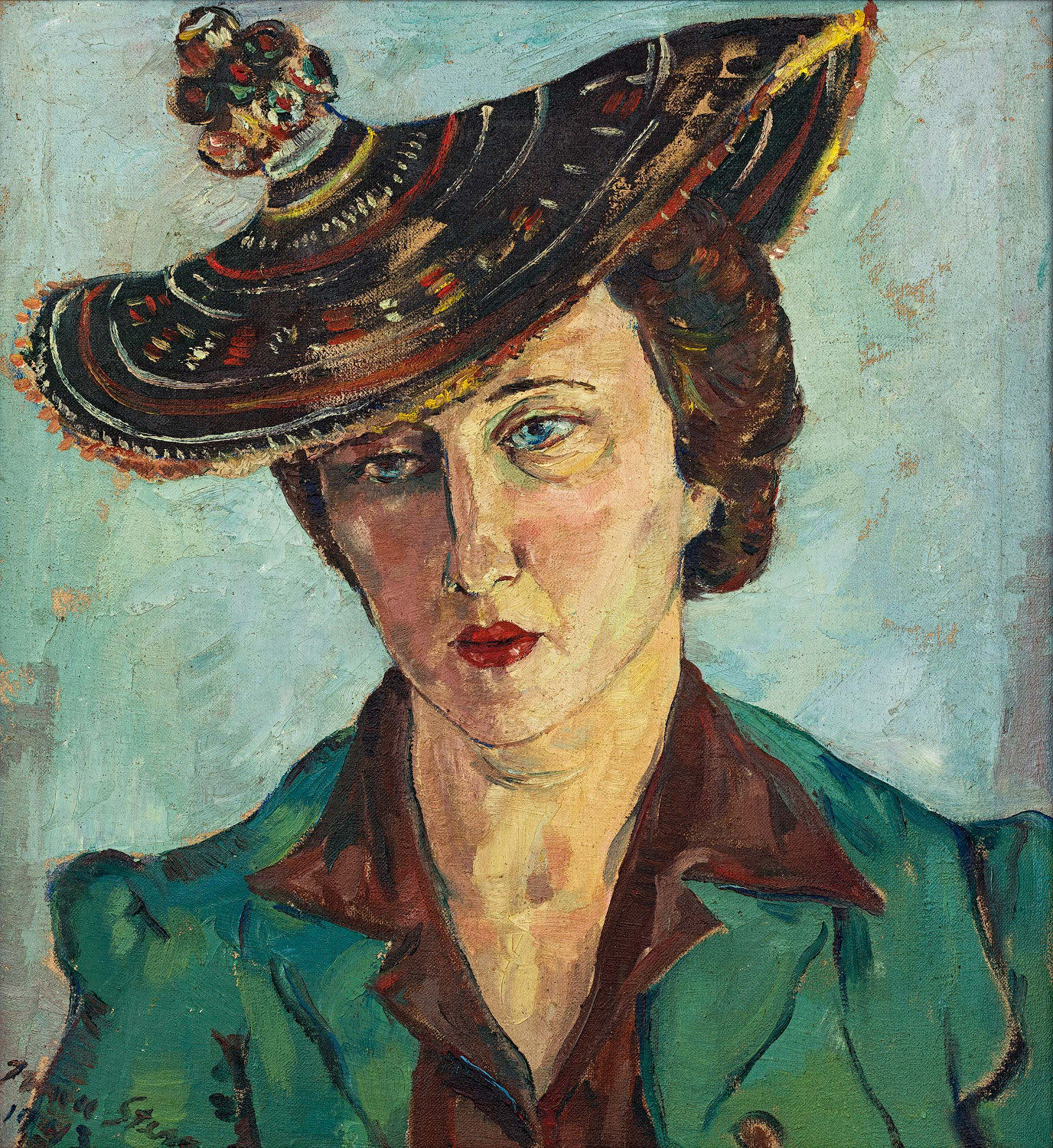

“Ugliness as a cult” was one of the Cape Town public’s common critiques of Irma Stern’s work from the 1920s onwards. As a white artist working in South Africa, her particular style of “native study” and her inclination to paint black people and culture were inspired by European modernists and their fascination for “primitivism”. Indeed in 1919 she started a journal titled Paradise, which can be associated to Paul Gauguin’s work or her mentor Max Pechstein’s depictions of figures in nature in the North Pacific Sea. She often expressed her dismay at the unfolding impact of colonialism in southern Africa where what she considered to be the ideal African way of life was disappearing in favour of “modernisation” and urbanisation.

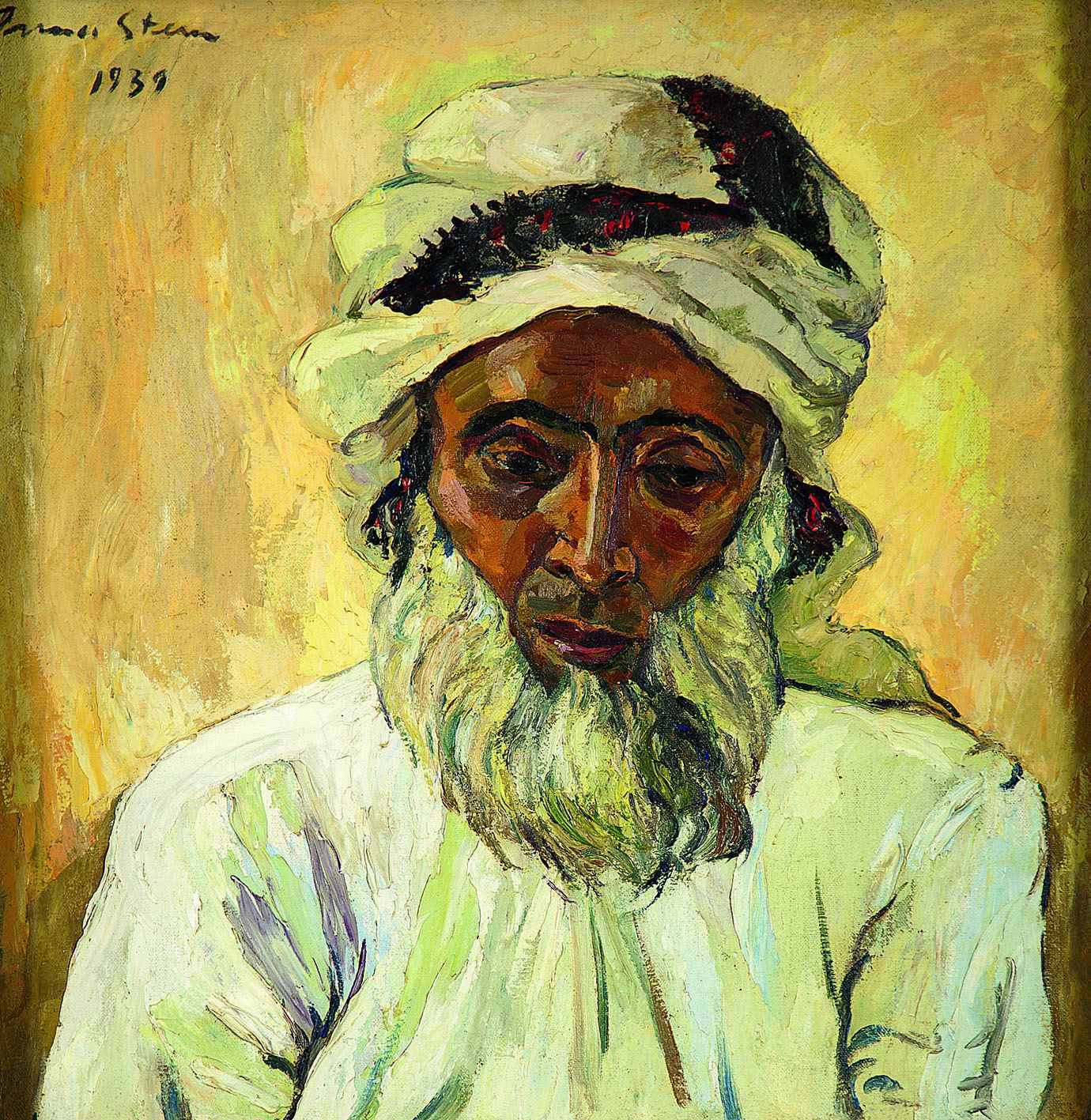

After the Second Boer War, her German-Jewish family returned to Germany, where she studied art in the 1910s. Stern was associated with German Expressionism but returned to Cape Town in 1920. She refused to return to Germany during the Nazi regime and instead visited Madeira, Senegal, Congo, Zanzibar, North Africa, Turkey, Spain and France, while also traveling extensively in South Africa.

Her use of dramatic, unrealistic, bold colours, stark contours, distorted forms and perspectives, flat motifs and free brushstrokes, are far removed from the typical academic painting in South Africa as represented for instance by Edward Roworth. She assembled a collection of artefacts (sculptures, fabrics, etc.) which appear in her still-life paintings and inspire her sculptures and elaborately carved wood and matting frames. Renowned for her portraits, such as The Watussi Chief’s Wife (1946), landscapes and graphic work, she also made ceramics. Her models go unnamed, as she appears more interested in the general rendering of certain ways of life or the picturesque motif, but the intensity of her stylisation and the vibrancy of her marking suggest a will to convey powerful and textured life forces rather than any pure ethnographic record. Some of her titles highlight her attention to the richness of African cultures, such as Swazi Girls, Xhosa Woman, Pondo Woman, The Fish God, Lake Kivu, Mangbetu, and the Jour du mouton, Tunis. Parallels are often made with the artist Maggie Laubser or with Constance Stuart Larrabee’s photographs in South Africa.

Stern was recognised for her artistic practice and exhibited in South Africa and in Europe from the 1940s on; her work was presented at the Venice Biennale several times in the 1950s, with particular focus in 1958. She was granted the Guggenheim Foundation National Award for South Africa in 1960. Having divorced to focus on her artistic practice, she lived most of her life in a house called The Firs in Rondebosch (Cape Town), which became the Irma Stern Museum in 1971.