Malvina Hoffman

Alexandre Arsène, Malvina Hoffman, Paris, Pouterman, 1930

→Kinkel Marianne, Races of mankind : the sculptures of Malvina Hoffman, Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 2011

Looking at ourselves, Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman, The Field Museum, Chicago, 15 January 2016 – 3 February 2019

American sculptor.

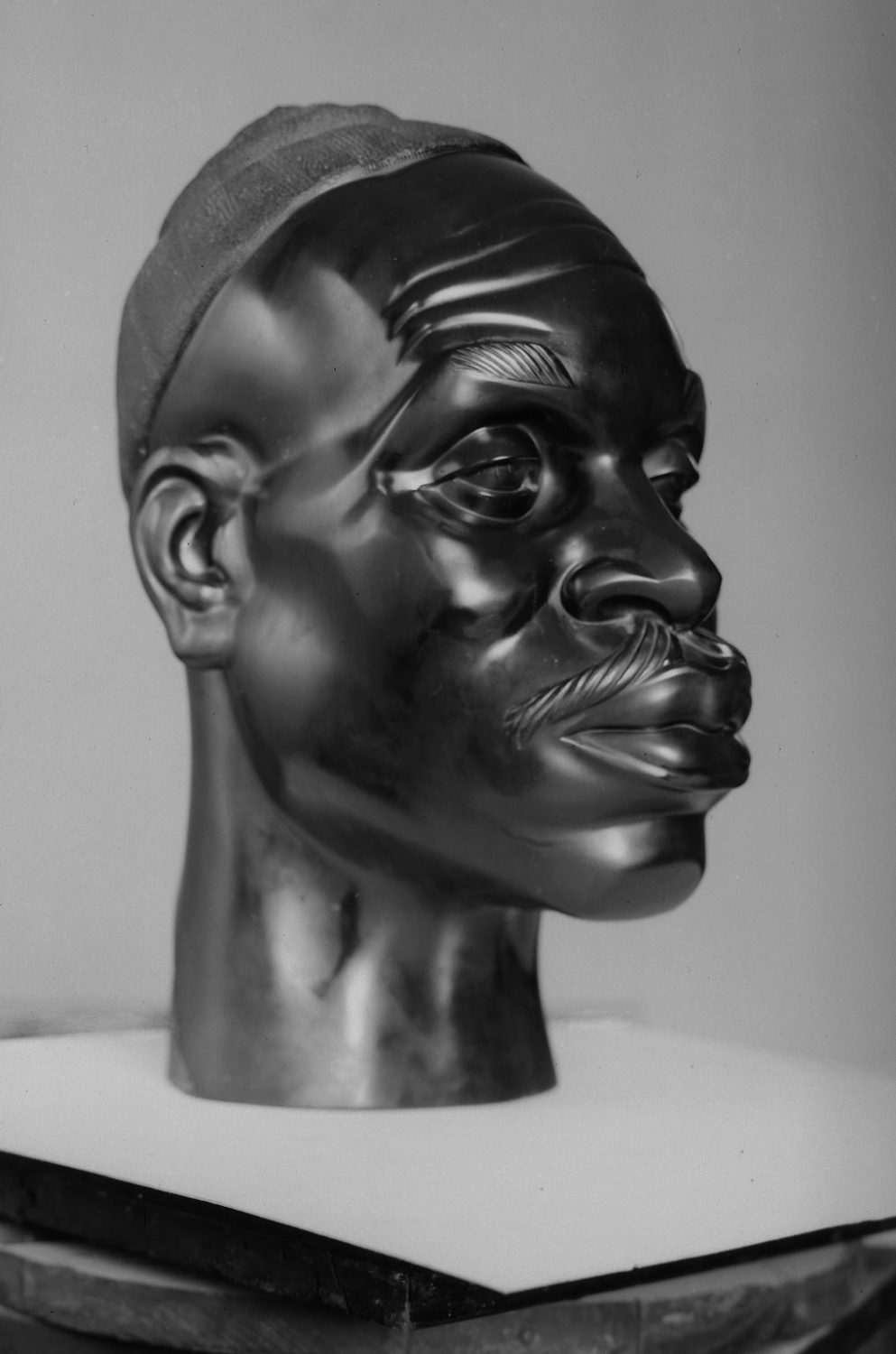

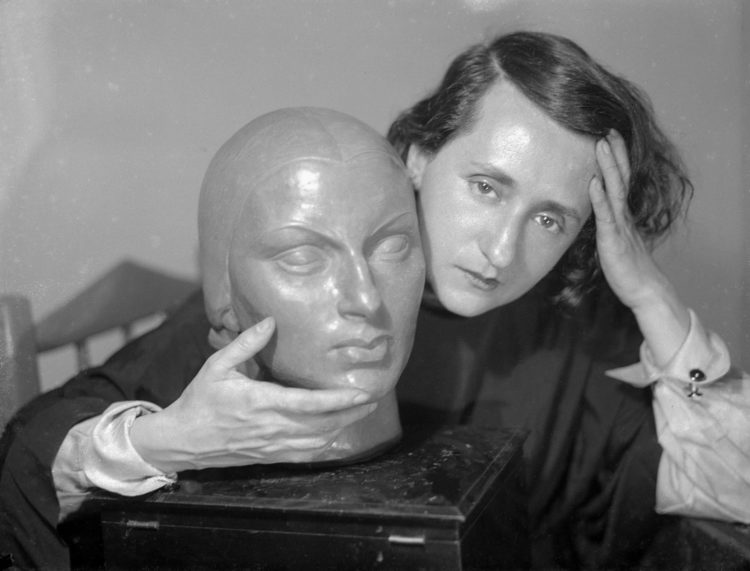

While her work is now mostly forgotten, perhaps because of the deeply disturbing nature of her major opus – a series of sculptures depicting human races – Malvina Hoffman, the daughter of a musician and wife of the violinist Samuel B. Grimson, attended the Women’s School of Design and the Art Students League, and studied under Rodin in 1910-1911. The teachings of the sculptor gave her effigies a sense of vital energy, with the polished figures emerging from the raw block of marble (Bust of John Keats, completed in 1923). She manifested an early interest in portraits, for which she strove to achieve a resemblance and harmony in detail specific to each model. The Russian Ballets in Paris provided her with her first subject of choice: the 24 panels of the Bacchanale Frieze (1915-1924) depict the various stages of the dancers’ movements and play with diagonals and the contortions of their loosening bodies, with waves of fabric extending the movement of the silhouettes. Hoffman also studied anatomy and learned to build armatures and to smelt and rework bronze. The Croatian sculptor Ivan Mestrovic taught her equestrian sculpture in Zagreb in 1927. The following year, she was commissioned by the Field Museum of National History in Chicago to create the Hall of Man. This considerable undertaking, inaugurated in 1933, comprised 104 life-size bronze figures meant to showcase the different races of mankind.

The artist ended the series with the features that she found the most problematic: the Aryan physiognomy, which Nazi ideologists at the time considered as the only perfect one. Although she had intended the work as an anthropological study, it would nonetheless come to be contested in scientific circles and considered deeply racist in the 60s. After World War II, Hoffman was commissioned to create sculptures for the Épinal American Cemetery.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

Malvina Hoffman at The Field Museum

Malvina Hoffman at The Field Museum

Conversation on Malvina Hoffman and Anna Pavlova

Conversation on Malvina Hoffman and Anna Pavlova