Maria Martins

Arruda Callado Ana, Maria Martins : uma biografia, Rio de Janeiro, Gryphus, 2004

→Ramos Graça, Maria Martins : escultora dos tropicos, Rio de Janeiro, Artviva, 2009

Maria Martins : exposição de escultura em ferro, Museu da Marinha, Lisbon, 28 March – 28 April 1991

→Maria Martins : metamorfoses, Museu de Arte Moderna de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, 10 June – 15 September 2013

Brazilian sculptor.

Maria Martins was always a marginal artist within the Brazilian art world. Her works combined Western, and especially surrealist, influences – the result of her perpetually nomadic life – with Amazonian forms and legends, which at the time were seldom explored by her fellow Brazilian artists. Born to a wealthy family, M. Martins studied at a French school in Rio de Janeiro, and was at first destined to become a professional musician. After her first marriage ended, she went to France and met the diplomat Carlos Martins Pereira e Souza, whom she married in 1926. She took a late interest in sculpture, but travelling alongside her husband enabled her to learn a variety of techniques: she studied in Paris under Catherine Barjansky; learnt woodcarving in Ecuador; was introduced to ceramics and took an interest in Zen philosophy in Japan; in Belgium, the expressionist sculptor Oscar Jespers taught her modelling based on the simplicity of his large wooden figures; in the US, where she lived between Washington and New York from 1939 to 1948, Jacques Lipchitz introduced her to bronze casting, which would eventually become her method of choice. She began to work with it by using the ancient Egyptian technique of lost-wax casting, to which she would add a little fat – a process which made the beeswax traditionally used in this process extraordinarily ductile, allowing her to cast narrow bronze liana shapes with unusual outgrowths. This long period spent in the US was her most productive. Her subjects, even the religious ones, explored the myriad ways in which the body – especially the female body – expresses itself. Whether they depicted Salome or, later on, the siren of the Amazon Yara rising from the waters, her small figures combined dance and sensuality in an increasingly loose manner. Heads, hands, and feet gradually became more and more distended. While in New York, she became acquainted with Marc Chagall and Piet Mondrian and, from 1942-1943, and joined the group of surrealists in exile (with André Breton, Max Ernst, André Masson, and Marcel Duchamp). Also during this period, she became known as “Maria”, and move closer to surrealist themes by adding short texts about desire to her works. The bodies she depicted became more and more complex, organic, plant-like, phantasmagorical, and often cruelly erotic. Her subjects, on the other hand, remained Brazilian-centred and drew liberally from Amazonian folklore.

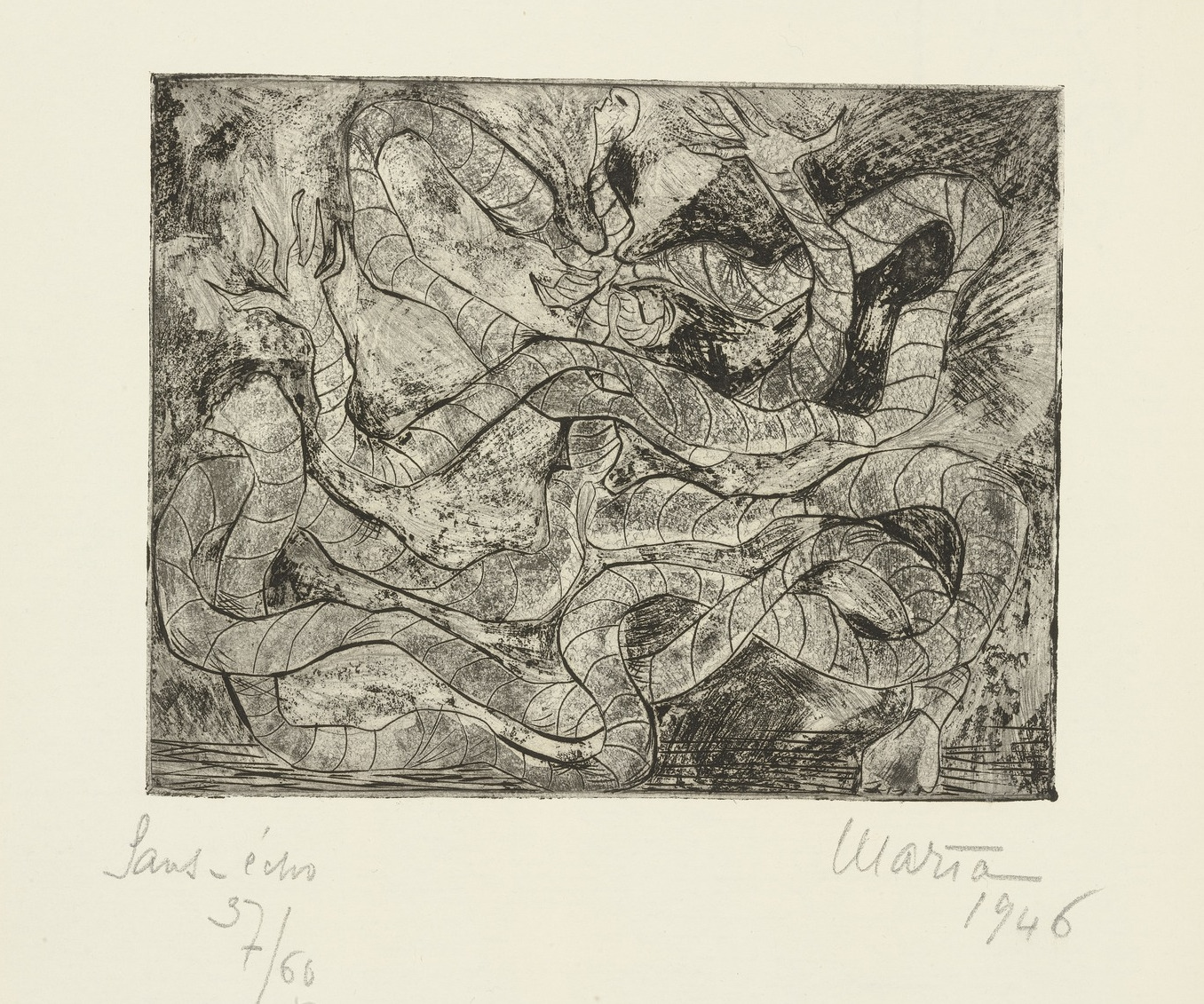

She focused first and foremost on the serpentine figures of reptiles and lianas – figures that stand at the intersection of Amazonian themes, of form (the sinuous torsions to which she subjects the bronze), and of surrealist inspiration. A. Breton saw in these works the vitalist and primitive impulse of the sacred flame that, according to him, was lacking in what he called “the West”. Therefore, Cobra grande (1946) personifies the goddess of goddesses; Amazonia depicts Cobra Norato, a figure of the Amazon who, to quench its appetite, consents to letting the forest grow again, in exchange of the yearly sacrifice of a young woman. The presence of the theme of cannibalism in her work was seen as a reference to the “anthropophagic” movement that marked Brazilian painting in the 1920s and emphasised an eroticism expressed by the abolition of form. As such, her bodies seem to evade the sculptor’s attempts to domesticate them, instead leaning toward the plant realm, branching out or reaching forward like polished or rugged creepers that evoke both the fusion of bodies in lovemaking and their fierce antagonism. Impossible (1946), of which she created multiple versions, opposes full-bodied, round and smooth hybrid creatures with protruding sharp tentacles representing both attraction and injury. It was around this time that her affair with M. Duchamp started. The pair met in 1943, and Duchamp dedicated one of his suitcases to her and made a moulding of her body for Étant donnés: 1. la chute d’eau 2. le gaz d’éclairage [Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas]. The piece, which can only be seen through two eye-level holes in a door, was begun in 1946, completed twenty years later, and only shown to the public after his death. In 1950, after spending two years in Paris, M. Martins returned to the constructivism and abstraction of Brazil, where her work was not well received, because it was still surrealist and figurative. She took part in a few more exhibitions, and helped found the first Venice Biennale in 1951 and the Museum of Modern Art in Rio in 1952, after which she turned to writing essays on poetry, Nietzsche, and China.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018