Remedios Varo

Garcia Catherine, Remedios Varo, peintre surréaliste ? : création au féminin, hybridations et métamorphoses, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2007

→Gil Antonio J. & Rivera Magnolia, Remedios Varo : el hilo invisible, Mexico City, Siglo XXI Editores, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, 2015

The magic of Remedios Varo, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington D.C., 10 February – 29 May 2000 ; Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, Chicago, 16 June – 20 August, 2000

→Adictos a Remedios Varo. Nuevo Legado 2018, Museo de arte moderno, Mexico City, 19 October 2018 – 28 February 2019

Spanish painter and writer.

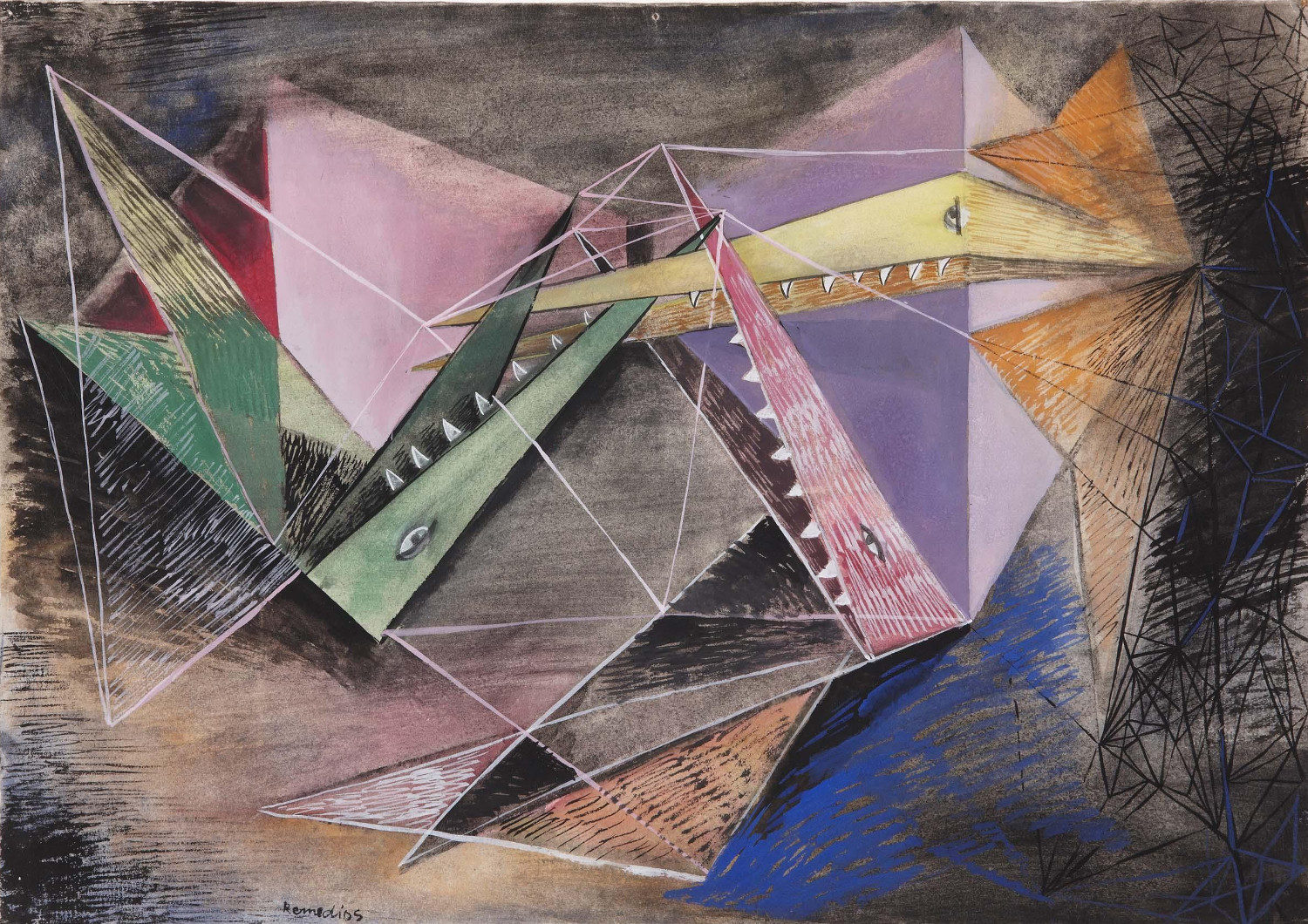

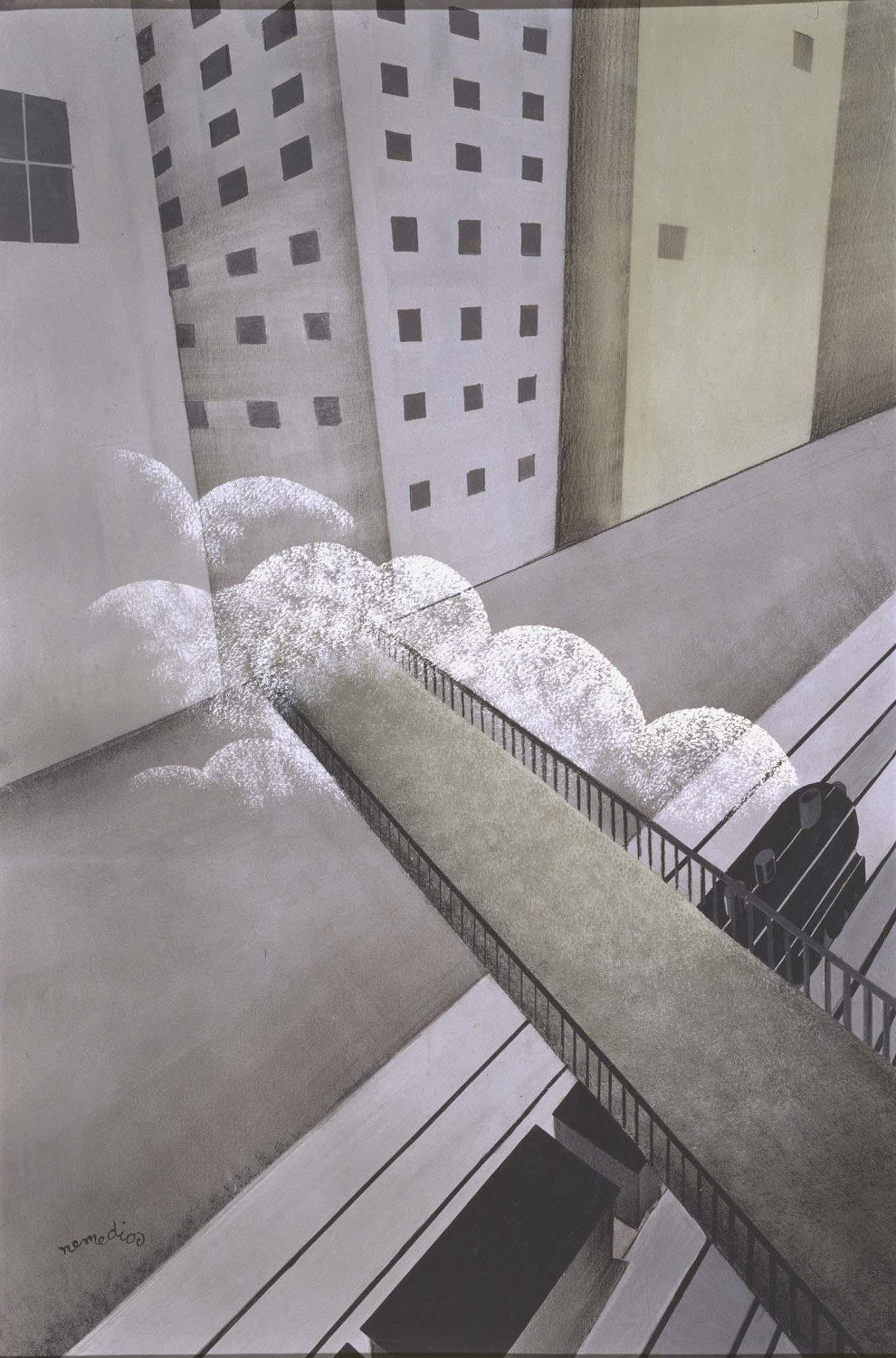

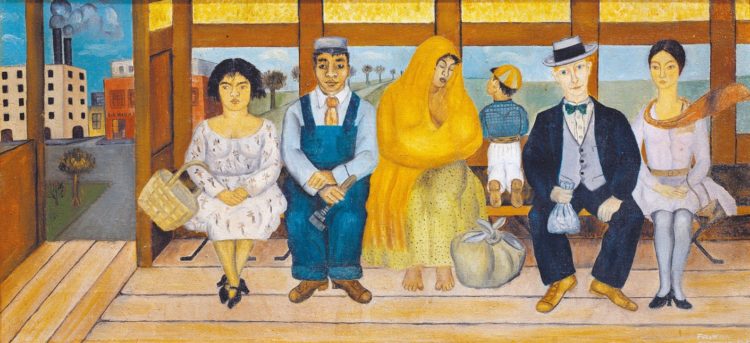

Although she was from Catalonia, Remedios Varo became one of the most important surrealist painters in Mexico. Her work carries the memory of her travels with her hydraulic engineer father and of her religious upbringing, through the figures of wandering pilgrims, machines, and young boarders. At the age of 17, she was one of the few women to gain admission to the prestigious Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid. She married the anarchist painter Gerardo Lizarraga in 1930 and settled in Barcelona, where she became friends with the surrealist painters Esteban Francés and Oscar Dominguez. She created collages (The Anatomy Lesson, 1935) and cadavres exquis, and communicated with Parisian surrealists through the intermediary of Marcel Jean. In 1936, she took part in the only exhibition of the Logicophobist Group, which believed in the connections between art, literature, and metaphysics. The following year, she accompanied the poet and essayist Benjamin Péret to Paris, but Franco’s regime would prevent her from ever returning to her country. Despite her participation in surrealist exhibitions, most of the pictorial work she produced in France was created as a means of subsistence. In 1939, B. Péret’s Marxist commitments led to her arrest and imprisonment. After the armistice, she and Victor Brauner relocated to the Villa Air-Bel in Marseille, where many other surrealists had also found refuge, before emigrating to Mexico in 1942. It was in Mexico that she would create most of her work.

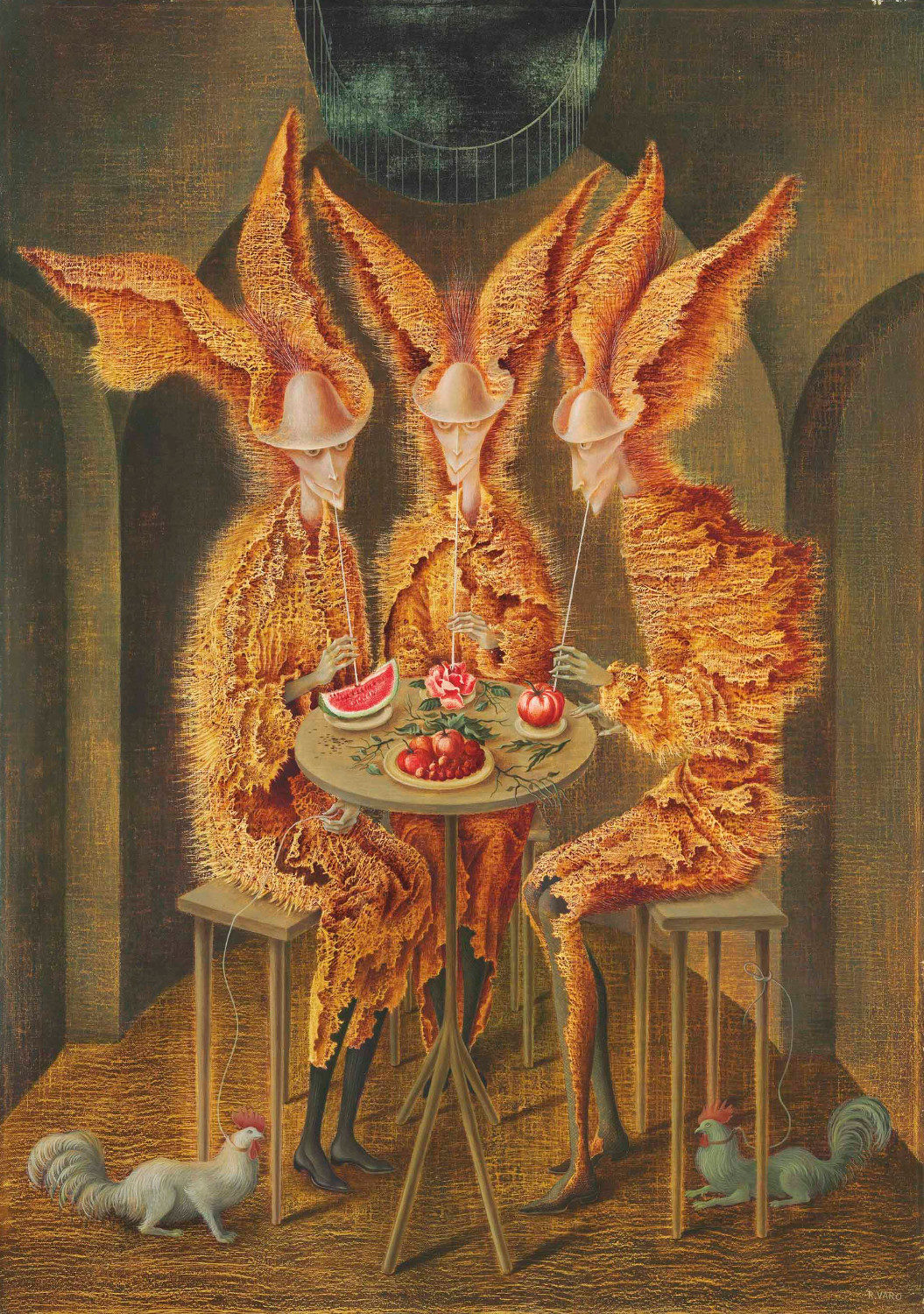

In the 1940s, she made dioramas and small theatre sets for the British antifascist propaganda office. She also worked as a decorator, a costume designer for the theatre, and an advertising illustrator for pharmaceutical companies. Her tiny publicity designs manifested both her taste for symbolic vocabulary and her phobia of insects, as well as the tremendous importance she attached to costumes and accessories as transitional spaces to the world of dreams and fantasy. However, it was only in 1953, when she began a relationship with the publisher Walter Gruen, that the artist found herself truly freed from material restrictions and was able to focus exclusively on her painting. She developed a highly personal style, combining techniques such as fumage, rubbing, and transfer printing to depict extremely detailed fantasy figures in the vein of Hieronymus Bosch. She became close friends with Leonora Carrington, with whom she shared a deep interest in the occult and a dark sense of humour. Her enthusiasm for the theories of esotericist George Gurdjieff, particularly his concept of the “transformational quest”, inspired her to paint the initiatory journeys of explorers and minstrels (Ascención al monte Análogo [The Ascension of Mount Analog], 1960). Her figures are depicted wandering through imaginary landscapes reminiscent of Piranesi or Escher (Arquitectura vegetal [Vegetal Architecture], 1962), riding ingenious vehicles that seem to merge with their bodies, thus creating hybrid beings in the vein of the flying creatures Goya imagined in his Disparates. One of these is the Homo rodans, a comical predecessor of the Homo sapiens, whose lower body is a wheel, and which she further described in her pseudo-archaeological treatise De Homo Rodans, also making a sculpted model of it from fowl and fish bones that same year. She also imagined study cabinets worthy of the Renaissance as settings for her initiatory journeys, for example in Creación de los aves (The Creation of the Birds, 1957), in which androgynous creatures can be seen carrying out alchemical experiments, sometimes used as metaphors of artistic creation (Música solar [Solar Music], 1955). In honour of the hundredth anniversary of her birth, Mexico listed her work as a national treasure.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019