Shirley Jaffe

Paul Frédéric, Suchère Éric (ed.), Shirley Jaffe, exh. cat., Domaine de Kerguéhennec, Bignan ; Frac Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand (3 April–25 May 2008 ; 29 June–21 September 2008), Bignan / Clermont-Ferrand, Domaine de Kerguéhennec / Frac Auvergne, 2008

→Rubinstein Raphael, Les Formes de la dislocation, Paris, Flammarion, 2014

Shirley Jaffe. Peintures (1980-1999), musée d’Art moderne de Céret, France, 1999

→Shirley Jaffe, Frac Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, 3 April–25 May 2008 ; Domaine de Kerguéhennec, Bignan, 29 June–21 September 2008

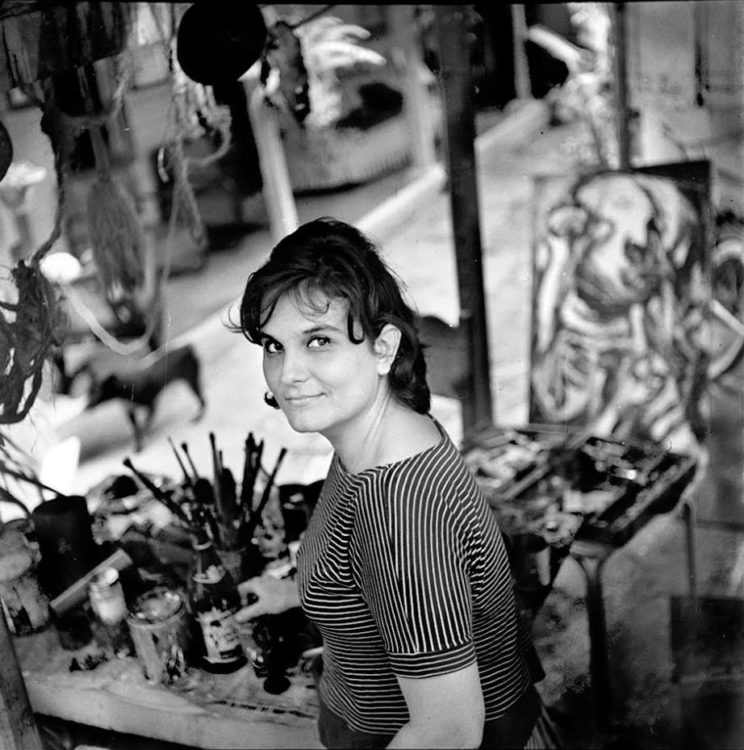

American painter.

Shirley Jaffe studied art at Cooper Union Art School in New York, then in Washington. She discovered Kandinsky at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and admired Bonnard’s later work. In 1949, she settled for good in Paris. Her friendships with Kimber Smith, Joan Mitchell, Sam Francis, Jean-Paul Riopelle and many others helped her to discover American abstract expressionism, of which they were the “second generation” representatives in France. In the 1950s, her painting abounded in great gestural energy; bright colours were worked in broad brush strokes. Forms foreshadowing her work to come barely emerged from that pictorial space. Her first group show was held at the Nina Dausset gallery in Paris in 1952. During one of her return visits to New York—she only ever made short stays in the United States—she felt abstract expressionism, gestural and matierist, had become a worn out rhetoric, and was keen to find her own path. From that early manner she retained an inspiration invariably based on spontaneity, as is illustrated by her sketches, which remained very gestural. In Berlin, between 1963 and 1967, she embarked on paintings which show a mixture of turmoil and order; the colours are dovetailed, covering each other, and spilling over, but already caught in the forms of a complex geometric organization. The “formal matrices” which the artist would subsequently favour—embedded lozenges, arabesques—made their appearance.

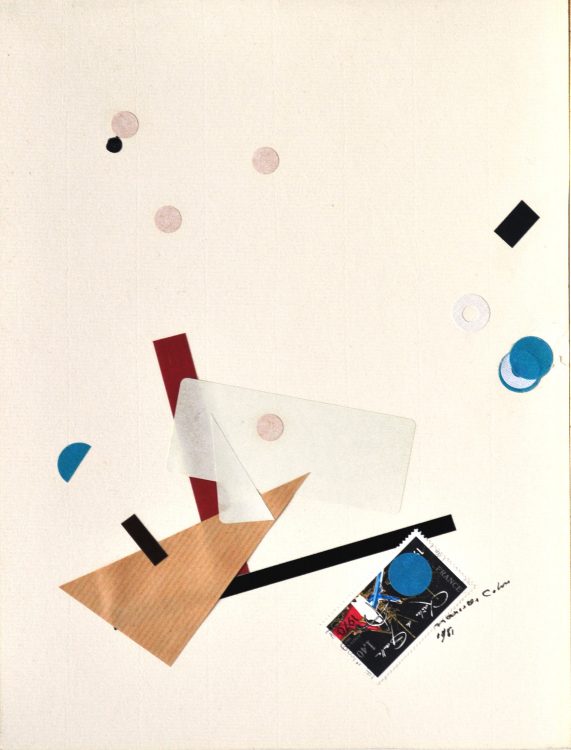

From 1968 on, and then in the 1970s, feeling “the need to be radical” and “start painting simply,” she abandoned gesture and paint for colour and geometry; the canvas’s surface became motionless; the composition was frontal; the much more matt colours were from then on applied as uniformly as possible, with no brush marks visible. The elements of the composition were contained in geometric forms—triangles, rectangles, trapezia, parallelograms—regularly joined together. From the 1980s, Jaffe’s oeuvre made a solid impact in the Paris art scene, in all its unusualness. Each painting formed a unity with the indivisible reality of a wall or mosaic. Here, the space of the picture was totally flattened; even the white acquired the hardness of a form and was raised to the same level as the coloured forms. The picture All Together (1995), with its witty title, neatly sums up her unique world, and her constant inventiveness based on a geometry which might be described as lyrical: in that inspiring place represented, for her, by the urban world, forms are overlaid and meet each other, the better to then diverge in unforeseen thrusts of spirals, loops, angles and waves… Just as the perpetually evolving city, with its construction and destruction, mixes straight and curved lines, motion and repose, so the canvas holds on to that idea, while at the same time doing away with anecdote and perspective.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Shirley Jaffe at Frac Auvergne

Shirley Jaffe at Frac Auvergne