Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Staber Margit, Sophie Taeuber–Arp, Lausanne, Rencontre, 1970

→Calzetta Jaeger Chiara, Sophie Taeuber : rythmes plastiques, réalités architecturales, Clamart, Fondation Arp, 2007

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, MoMa, New York, 17 September–13 December 1981

→Sophie Taeuber-Arp, musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1989

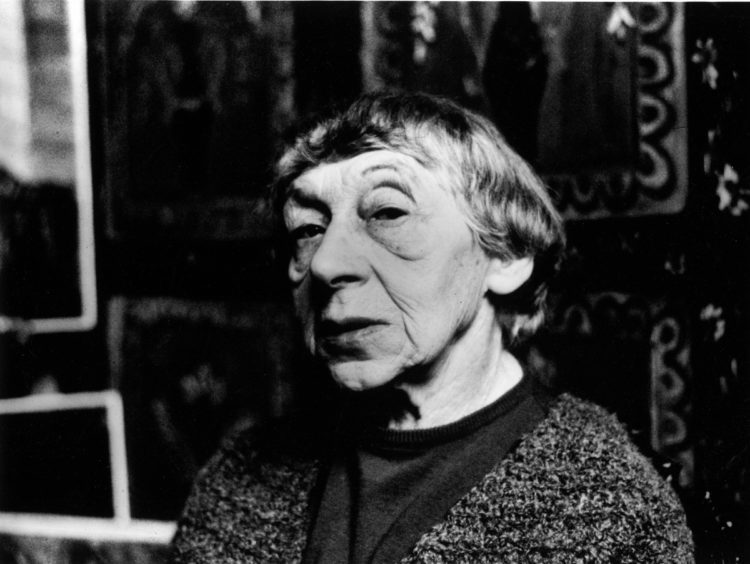

Swiss painter, sculptress, dancer and textile artist who took French nationality.

The daughter of a German father and Swiss-German mother, Sophie Taeuber grew up in an environment in which art and culture were part of daily life. In St Gallen she learned textile design, embroidery and lacework, then studied in the “experimental studios” of Hermann Obrist and Wilhelm von Debschitz in Munich where she learned a variety of techniques, including woodworking and architecture. In 1912–13 she studied weaving at the Decorative Arts School in Hamburg. She met the painter and poet Hans (or Jean) Arp in Zurich in November 1915 and joined him in the Dada movement. They married in 1922. Her participation in the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts took her to Paris in 1925 where the couple, who would obtain French nationality the following year, frequented the Surrealists. Their house-cum-studio was an international artistic meeting place between 1929 and 1939. Sophie Taeuber-Arp joined the Cercle et Carré and Abstraction–Creation associations. Together with César Domela, Hans Arp and New York collectors and patrons, she published the multilingual review Plastique (1937–39) until just before the war. Highly concerned by the political turn of events, she strove to make fresh contact with those artists who had dispersed from Paris. Her exodus with her husband took them to Grasse where, with Alberto Magnelli and Sonia Delaunay, they created drawings that clearly expressed their anti-fascist commitment. Following the failure of their plan to emigrate to the United States, the couple took refuge in Switzerland in November 1942. The death of Sophie Taeuber-Arp in Zurich on 13 January 1943 remains a puzzle.

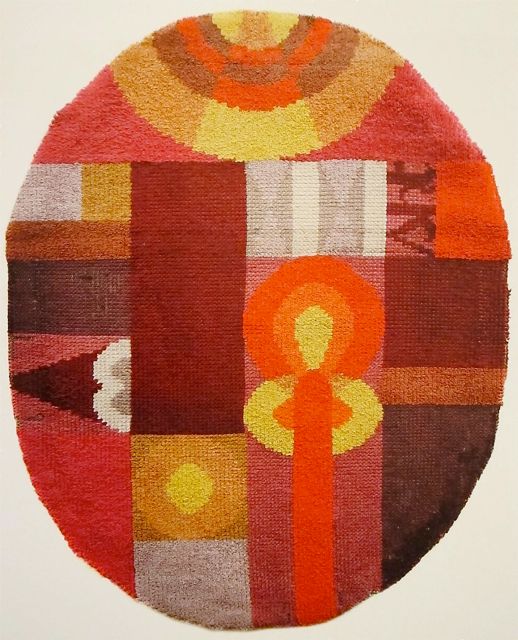

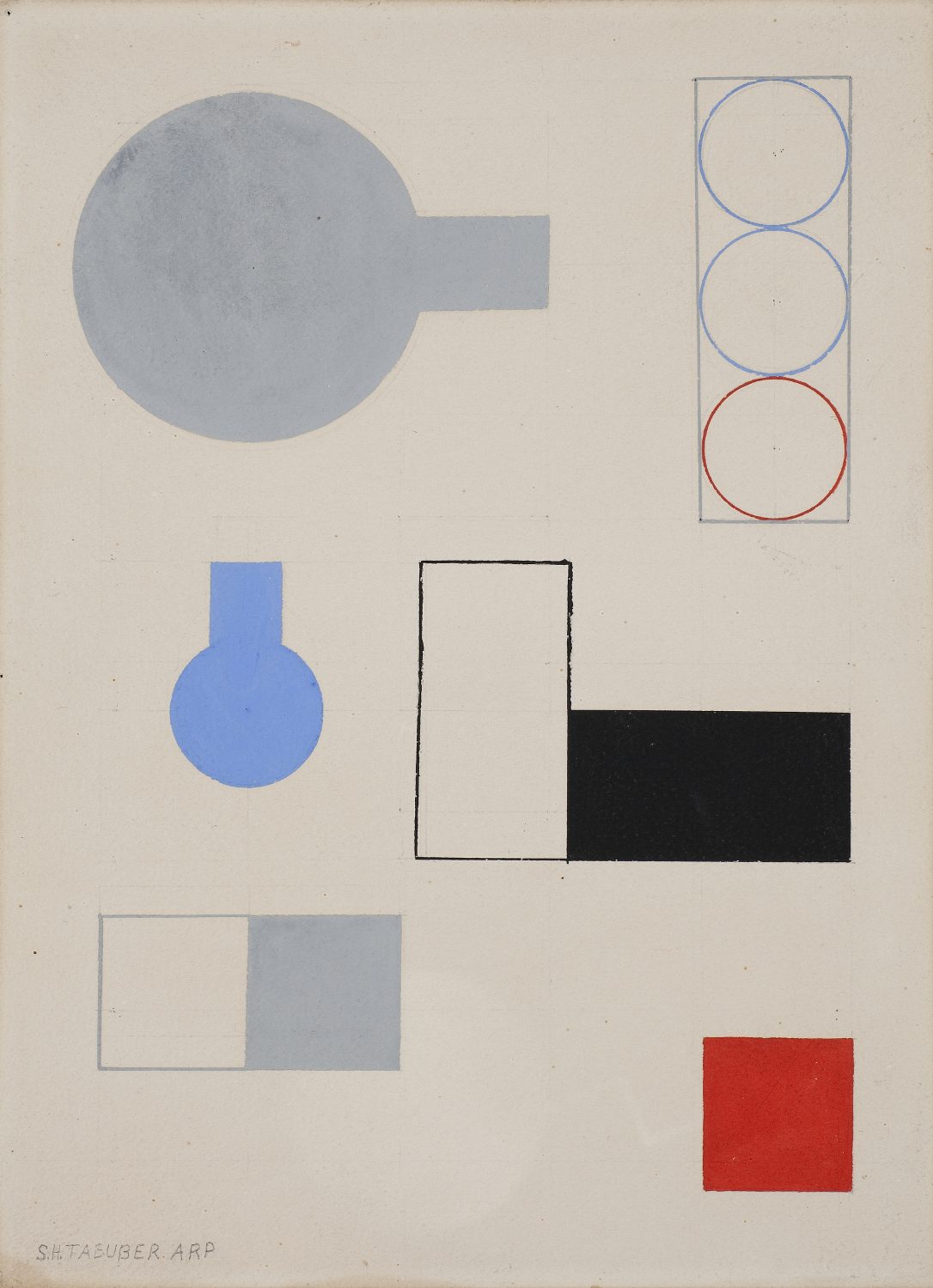

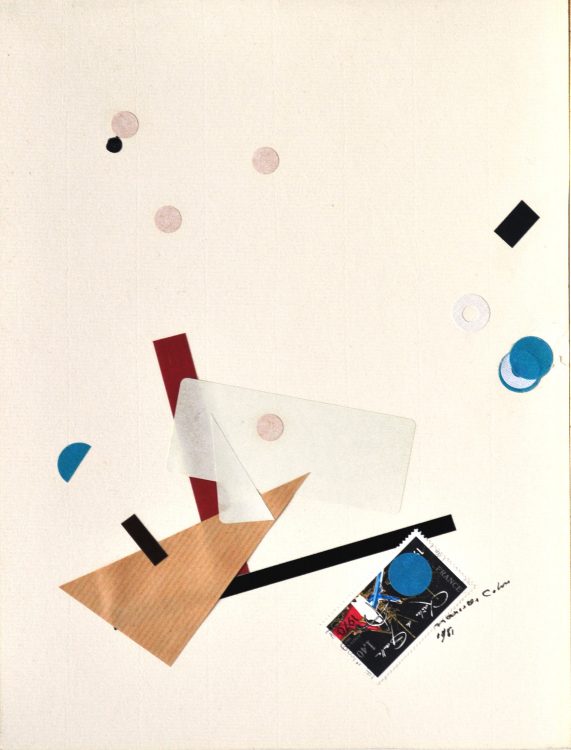

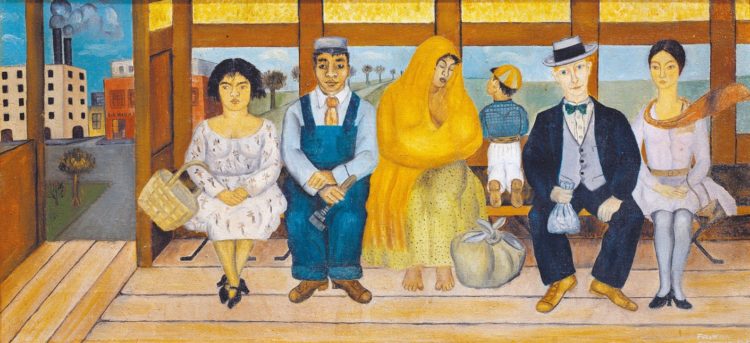

This artist’s multifaceted work is a true artistic synthesis. A pupil of Rudolph von Laban, she was involved in research into dance and choreographic notation from 1915 in Zurich and the Monte Verità colony of artists in Canton Ticino. With her friend Mary Wigman, she introduced dance into the Dada movement at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. She took up plastic creation as a result of her experience of working with textiles, both theoretic and practical. Taking her point of departure as the vertical and horizontal intersection that governs weaving, she designed orthogonal patterns in coloured crayon. Her designs (Vertical-Horizontal Composition, 1915–16) were produced at the same time as the works of Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian, the pair recognized for the introduction of geometric abstraction. A pioneer of geometric concrete art in Switzerland (Vertical-Horizontal Composition with Reciprocal Triangles, 1918), her plastic language influenced her husband and together the couple produced such works as the series Duo-Collage (1918–19). During the years of Dada, she tackled three-dimensional creation by means of turned and painted wood, in which she played on the object-sculpture dynamic with a two-part container (Dada Bowl, 1916). This was followed by similar sculptures that she created with her husband. The originality of her puppets created in 1918 brought her public recognition. Among the Heads she produced in painted turned wood were the Portrait of Jean [Hans] Arp(1918), her self-portrait Head (1920) and Dada Head (1920), a true “Dadaist plastic manifesto”.

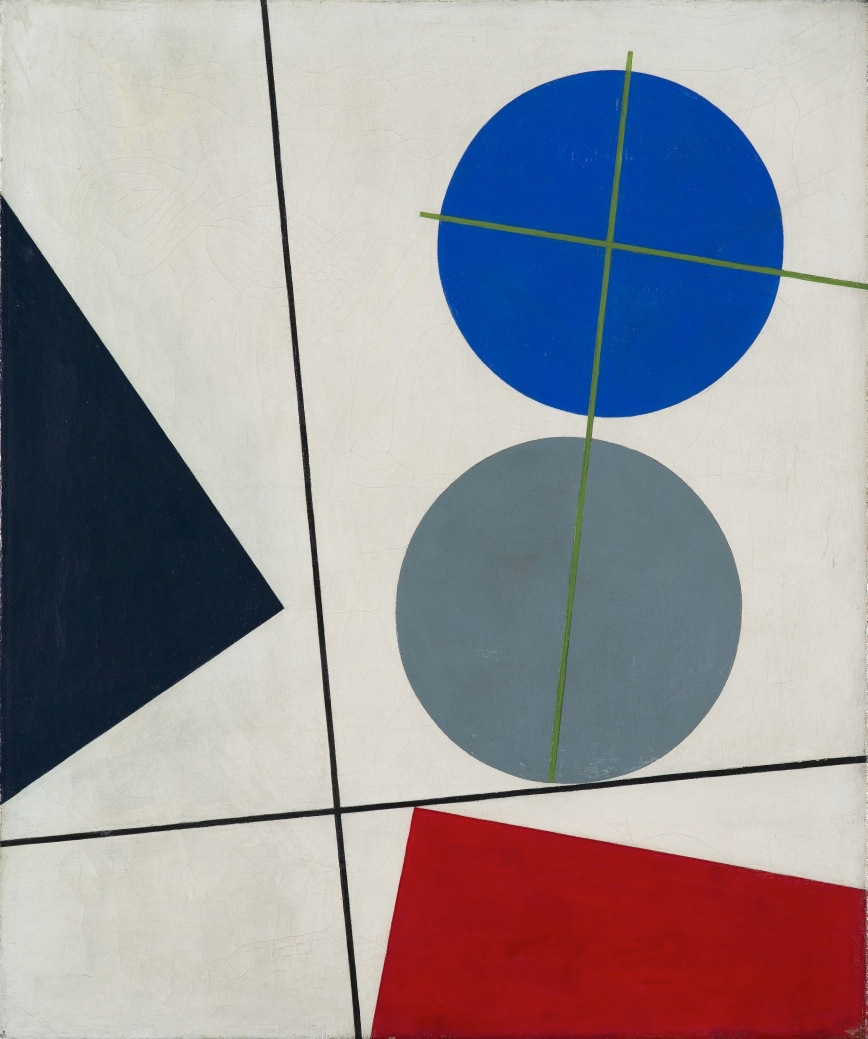

In Strasbourg between 1926 and 1928 she executed large mural paintings and stained-glass windows, and worked with Hans Arp and Theo van Doesburg on the interior decoration of the building called the Aubette in 1928, a creation that has been referred to as the “Sistine Chapel of modernity”. She would later produce a large number of reliefs and paintings along this line. Heralding Minimalism and Op Art, during the 1930s Sophie Taeuber-Arp introduced new plastic concepts through her Space Pictures, in which vertical and horizontal lines, crosses, diagonals and circles compose the balance (Four Spaces with a Broken Cross, 1932; Échelonnement désaxé, 1934). In her series Moving Circles(1934), she investigated the form of the circle. Her painted woodcuts of the 1930s merge painting and sculpture, in which plastic compositions tend towards spatial and even architectural constructions, and represented the outcome of her research. Artists in both Europe and the Americas would be influenced by her constructed works that explore the notions of the grid, the module and series, and which give priority to experimentation. Through her blend of the rational and poetic, Sophie Taeuber-Arp became a “luminous figure” in the development of abstract art.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Sophie Taeuber Arp : une inconnue célèbre

Sophie Taeuber Arp : une inconnue célèbre